2001â2002 - California Sea Grant - UC San Diego

2001â2002 - California Sea Grant - UC San Diego

2001â2002 - California Sea Grant - UC San Diego

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Surf-Zone Drifters: A New Tool for Studying Nearshore Circulation<br />

With <strong>California</strong> <strong>Sea</strong> <strong>Grant</strong> funding, coastal oceanographers<br />

have built a satellite-tracked drifter capable of withstanding<br />

the pounding force of breaking waves. The surf-zone<br />

drifter, the first of its kind, represents an important addition to an ever<br />

increasingly sophisticated arsenal of tools for studying the coastal ocean.<br />

Unlike current meters, which measure water velocities at fixed points, the<br />

new drifter moves with ocean currents, tracing out a trajectory that<br />

represents the space-time evolution of a water parcel through the surf<br />

zone. These trajectories make it possible to unravel some of the more<br />

subtle physics of surf-zone circulation, such as the evolution and development<br />

of rip currents.<br />

The new instrument also has many potential applications for coastal<br />

communities interested in maintaining beach water quality. A fleet of the<br />

drifters, for instance, could be used to help estimate the rate at which<br />

water along the coast is exchanged with deeper, cleaner waters outside the<br />

surf zone. This exchange rate in turn could be used to help quantify the<br />

dispersion and fate of coastal pollution from point sources and urban<br />

runoff. The drifters could also conceivably be used to help coastal engineers<br />

evaluate the effects of jetties, groins, artificial reefs or seawalls on<br />

nearshore circulation, sand loss and coastal erosion.<br />

The drifter, designed by <strong>Sea</strong> <strong>Grant</strong> trainee Wilford Schmidt and engineers<br />

Brian Woodward and Kimball Millikan, all of Scripps Institution of<br />

Oceanography, stands about a meter tall and looks like a long white can<br />

with an antenna sticking out the top. Its exterior hull is made of white<br />

polyvinyl chloride (PVC) piping. <strong>Sea</strong>led inside, there is a Global Positioning<br />

System receiver, a data logger and a radio transmitter. There are also<br />

batteries and an internal lead weight for ballasting.<br />

Each drifter receives its position from earth-orbiting satellites and<br />

transmits its position to a shore-based tracking system, making it possible<br />

for researchers to monitor the movements of many drifters on a single plot<br />

in real-time.<br />

18<br />

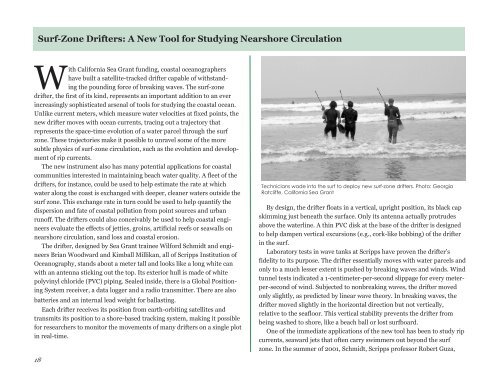

Technicians wade into the surf to deploy new surf-zone drifters. Photo: Georgia<br />

Ratcliffe, <strong>California</strong> <strong>Sea</strong> <strong>Grant</strong><br />

By design, the drifter floats in a vertical, upright position, its black cap<br />

skimming just beneath the surface. Only its antenna actually protrudes<br />

above the waterline. A thin PVC disk at the base of the drifter is designed<br />

to help dampen vertical excursions (e.g., cork-like bobbing) of the drifter<br />

in the surf.<br />

Laboratory tests in wave tanks at Scripps have proven the drifter’s<br />

fidelity to its purpose. The drifter essentially moves with water parcels and<br />

only to a much lesser extent is pushed by breaking waves and winds. Wind<br />

tunnel tests indicated a 1-centimeter-per-second slippage for every meterper-second<br />

of wind. Subjected to nonbreaking waves, the drifter moved<br />

only slightly, as predicted by linear wave theory. In breaking waves, the<br />

drifter moved slightly in the horizontal direction but not vertically,<br />

relative to the seafloor. This vertical stability prevents the drifter from<br />

being washed to shore, like a beach ball or lost surfboard.<br />

One of the immediate applications of the new tool has been to study rip<br />

currents, seaward jets that often carry swimmers out beyond the surf<br />

zone. In the summer of 2001, Schmidt, Scripps professor Robert Guza,