Royal Society - David Keith

Royal Society - David Keith

Royal Society - David Keith

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

• activities (and/or substances) which are localised<br />

(intensive), or are widely distributed or dispersed<br />

(extensive);<br />

• effects which are primarily local/regional, or which are<br />

of global extent;<br />

• ‘big science’ and centralised control, or small-scale<br />

activity and local control;<br />

• processes which are perceived as familiar, or novel and<br />

unfamiliar (see also Box 4.4).<br />

Some geoengineering options (such as reflectors in space)<br />

have provoked public concern about potential militarisation<br />

(Submission: Robock). To some extent, these concerns<br />

have already been addressed in international law through<br />

the 1977 Convention on the Prohibition of Military or<br />

Any Other Hostile Use of Environmental Modification<br />

Techniques (ENMOD), UNCLOS, and the 1967 OST.<br />

Other concerns have been expressed about the desirability<br />

of commercial involvement in the development and<br />

promotion of geoengineering. There are already a number<br />

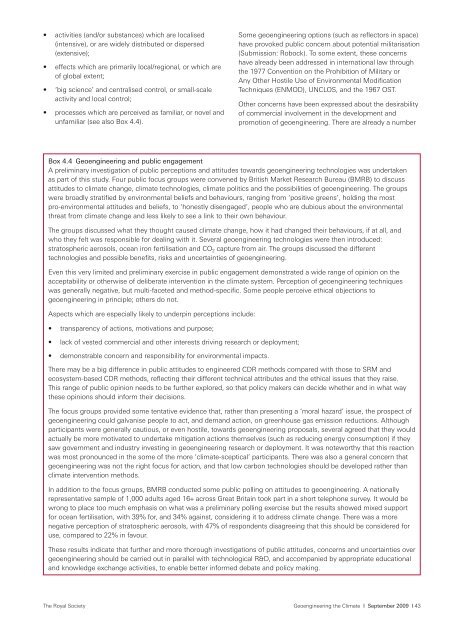

Box 4.4 Geoengineering and public engagement<br />

A preliminary investigation of public perceptions and attitudes towards geoengineering technologies was undertaken<br />

as part of this study. Four public focus groups were convened by British Market Research Bureau (BMRB) to discuss<br />

attitudes to climate change, climate technologies, climate politics and the possibilities of geoengineering. The groups<br />

were broadly stratified by environmental beliefs and behaviours, ranging from ‘positive greens’, holding the most<br />

pro-environmental attitudes and beliefs, to ‘honestly disengaged’, people who are dubious about the environmental<br />

threat from climate change and less likely to see a link to their own behaviour.<br />

The groups discussed what they thought caused climate change, how it had changed their behaviours, if at all, and<br />

who they felt was responsible for dealing with it. Several geoengineering technologies were then introduced:<br />

stratospheric aerosols, ocean iron fertilisation and CO 2 capture from air. The groups discussed the different<br />

technologies and possible benefits, risks and uncertainties of geoengineering.<br />

Even this very limited and preliminary exercise in public engagement demonstrated a wide range of opinion on the<br />

acceptability or otherwise of deliberate intervention in the climate system. Perception of geoengineering techniques<br />

was generally negative, but multi-faceted and method-specific. Some people perceive ethical objections to<br />

geoengineering in principle; others do not.<br />

Aspects which are especially likely to underpin perceptions include:<br />

• transparency of actions, motivations and purpose;<br />

• lack of vested commercial and other interests driving research or deployment;<br />

• demonstrable concern and responsibility for environmental impacts.<br />

There may be a big difference in public attitudes to engineered CDR methods compared with those to SRM and<br />

ecosystem-based CDR methods, reflecting their different technical attributes and the ethical issues that they raise.<br />

This range of public opinion needs to be further explored, so that policy makers can decide whether and in what way<br />

these opinions should inform their decisions.<br />

The focus groups provided some tentative evidence that, rather than presenting a ‘moral hazard’ issue, the prospect of<br />

geoengineering could galvanise people to act, and demand action, on greenhouse gas emission reductions. Although<br />

participants were generally cautious, or even hostile, towards geoengineering proposals, several agreed that they would<br />

actually be more motivated to undertake mitigation actions themselves (such as reducing energy consumption) if they<br />

saw government and industry investing in geoengineering research or deployment. It was noteworthy that this reaction<br />

was most pronounced in the some of the more ‘climate-sceptical’ participants. There was also a general concern that<br />

geoengineering was not the right focus for action, and that low carbon technologies should be developed rather than<br />

climate intervention methods.<br />

In addition to the focus groups, BMRB conducted some public polling on attitudes to geoengineering. A nationally<br />

representative sample of 1,000 adults aged 16+ across Great Britain took part in a short telephone survey. It would be<br />

wrong to place too much emphasis on what was a preliminary polling exercise but the results showed mixed support<br />

for ocean fertilisation, with 39% for, and 34% against, considering it to address climate change. There was a more<br />

negative perception of stratospheric aerosols, with 47% of respondents disagreeing that this should be considered for<br />

use, compared to 22% in favour.<br />

These results indicate that further and more thorough investigations of public attitudes, concerns and uncertainties over<br />

geoengineering should be carried out in parallel with technological R&D, and accompanied by appropriate educational<br />

and knowledge exchange activities, to enable better informed debate and policy making.<br />

The <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Society</strong><br />

Geoengineering the Climate I September 2009 I 43