NAUTILUS P01 OCTOBER 2010.qxd - Nautilus International

NAUTILUS P01 OCTOBER 2010.qxd - Nautilus International

NAUTILUS P01 OCTOBER 2010.qxd - Nautilus International

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

24 | telegraph | nautilusint.org | October 2010 October 2010 | nautilusint.org | telegraph | 25<br />

TECHNOLOGY<br />

TECHNOLOGY<br />

Get ECDIS<br />

to work<br />

for you …<br />

Compulsory carriage of electronic charts is on the way<br />

for shipping. In this special report, chart agents Thomas<br />

Gunn consider the best ways of making the system work<br />

to everyone’s benefit<br />

O<br />

Only a type-approved electronic chart display and<br />

information system (ECDIS) operating with up-todate<br />

electronic navigational charts (ENCs) and with<br />

appropriate back-up may be used to replace all paper charts on<br />

a vessel.<br />

Where ENCs are not yet available, IMO regulations allow flag<br />

states to authorise the use of raster navigational charts (RNCs)<br />

together with an appropriate folio of paper charts. Note that in<br />

all other cases the vessel must carry all paper charts necessary for<br />

its intended voyage.<br />

From the regulatory perspective, the most important statement<br />

about the legal status of ECDIS is contained in the amended<br />

Chapter V of the SOLAS Convention, set into force on 1 July<br />

2002. ECDIS is specifically referred to in Regulation 19 ‘Carriage<br />

requirements for shipborne navigational systems and equipment’.<br />

However, in order to replace paper charts, such systems must<br />

fulfil considerable technical requirements laid down in ECDIS<br />

performance standards:<br />

zthe chart data in use must be official — ENCs where these are<br />

available — and the graphic display on the screen must meet the<br />

equipment-independent specification<br />

zthe equipment must support the full range of navigational<br />

functions that can be performed on the traditional paper<br />

charts.<br />

O<br />

No electronic system is completely failsafe. IMO performance<br />

standards therefore require that the ‘overall<br />

system’ includes both a primary ECDIS and an adequate<br />

independent back-up arrangement that provides:<br />

zindependent facilities enabling a safe takeover of the ECDIS<br />

functions in order to ensure that a system failure does not result<br />

in a critical situation<br />

za means to provide for safe navigation for the remaining part<br />

of the voyage in case of ECDIS failure<br />

However, these rather basic statements allow considerable<br />

leeway and there are various interpretations of the minimum<br />

functional requirements, or what constitutes ‘adequate’ backup<br />

arrangements.<br />

There are two commonly accepted options:<br />

za second ECDIS, connected to an independent power supply<br />

and a separate GPS position input<br />

zan appropriate up-to-date folio of official paper charts for the<br />

intended voyage<br />

Some flag states may permit other options (eg radar-based<br />

systems such as ‘Chart-Radar’). Shipowners should consult<br />

their national maritime administration for specific advice in<br />

Interpreting MSC 232/82 and, in a documented risk assessment,<br />

show that with regards to equipment and SMS procedures compliance<br />

has been achieved, and measures are in place to allow the<br />

mariner and vessels to comply with this.<br />

O<br />

Unlike the paper chart, ECDIS is a highly sophisticated<br />

system which, besides the navigational functions,<br />

includes components of a complex, computer-based<br />

information system. In total, the system includes hardware,<br />

operating system, ECDIS software (kernel and user interface),<br />

sensor input interfacing, electronic chart data, rules for presentation<br />

and display, status and parameters of alarms and indications.<br />

All these items are accessed through an appropriate humanmachine<br />

interface. As such, care must be taken when navigating<br />

with ECDIS to avoid false operation, misinterpretation, malfunction<br />

or — even worse — over-reliance on this highly-automated<br />

navigation system<br />

As with any type of shipboard navigation equipment, it can<br />

only be as good as those who use it and what it is being used for.<br />

In the case of ECDIS and electronic charts, if mariners are well<br />

trained the system provides the information flow that they need<br />

to make good decisions and therefore contributes significantly<br />

to safe and efficient navigation.<br />

The STCW Convention now has specific regulation<br />

and references to ECDIS training<br />

Stated another way, an ECDIS is another tool to enable mariners<br />

to perform their job better. However, just having some<br />

‘knowledge’ about ‘functions’ and ‘operational controls’ is insufficient<br />

to maximise the benefits of ECDIS. Proper training is<br />

absolutely necessary.<br />

O<br />

ECDIS and other electronic charting systems have<br />

become increasingly important to ship navigation<br />

and are already widely used either as a primary navigation<br />

tool or as an aid to navigation.<br />

The systems are increasingly complex, and require adequate<br />

and appropriate training in order to be operated correctly and<br />

safely. Without proper training, these systems will not be used<br />

to their full potential and could, under some circumstances,<br />

increase the hazard to navigation.<br />

The Standards of Training, Certification & Watchkeeping and<br />

<strong>International</strong> Safety Management codes put the responsibility<br />

firmly on the shipowner to ensure that mariners on their vessels<br />

are competent to carry out the duties they are expected to<br />

perform. If a ship is fitted with ECDIS, the owner has a duty to<br />

ensure that users are properly trained in the operation and use of<br />

electronic charts and are familiar with the shipboard equipment<br />

before using it operationally at sea.<br />

There is now specific regulation and reference to ECDIS<br />

systems in the STCW Convention, following the diplomatic<br />

conference in Manila in July. Additionally, since ECDIS systems<br />

are related to electronic charts, references to them are considered<br />

to be included in the material covered by the word ‘chart’.<br />

To encourage effective ECDIS education, the IMO approved<br />

a standardised model course for training on the operational<br />

use of ECDIS in 1999 (IMO course 1.27). This course is offered by<br />

approved training institutions and maritime academies. Maritime<br />

administrations can provide information on approved<br />

institutions. Some flag states have developed their own ECDIS<br />

training courses in order to be able to recognise the training<br />

certificates.<br />

Type specific ECDIS training is provided by equipment manufacturers.<br />

O<br />

Navigating with ECDIS is fundamentally different<br />

from navigating with paper charts. Important bridge<br />

work processes are significantly affected — in particular,<br />

voyage planning and voyage execution task. These require<br />

careful analysis and consideration.<br />

ECDIS provides a number of additional planning functions<br />

and features such as safety contours, alarms, and click-and-drop<br />

facilities for waypoints and markers. Whilst in many ways ECDIS<br />

makes voyage planning easier, it is still possible to make errors.<br />

However, these are likely to be of a different type from those<br />

encountered when using paper charts.<br />

Even though ENC coverage is increasing rapidly, many vessels<br />

will, to some degree, have to operate a dual — or even triple<br />

— system with ENCs, paper and raster charts. Planning and<br />

validation of the route has therefore to consider issues such as<br />

which chart types are available for the various segments of the<br />

voyage.<br />

The format of the voyage plan is likely to differ from the traditional<br />

alphanumeric lists of waypoints used with paper charts<br />

and should include information on the usability of connected<br />

electronic navigational devices such as GPS and AIS and their<br />

actual alarm settings.<br />

It is essential to make use of the in-built automatic check<br />

functions provided by ECDIS when validating and approving<br />

the voyage plan. Thought also needs to be given to ensuring that<br />

a back-up to the voyage plan on the ECDIS is available in case of<br />

equipment failure.<br />

It is important that there is good communication of the voyage<br />

plan to all bridge officers so that they are prepared for the<br />

intended voyage. This should include information on equipment<br />

status and back-up procedures.<br />

At the beginning of the voyage, as well as at any change of<br />

watch, the officers should review the voyage plan and agree the<br />

selected pre-settings of functions, alarms and indicators to be<br />

used on the ECDIS.<br />

Where vessels carry paper charts as well as an ECDIS, the role<br />

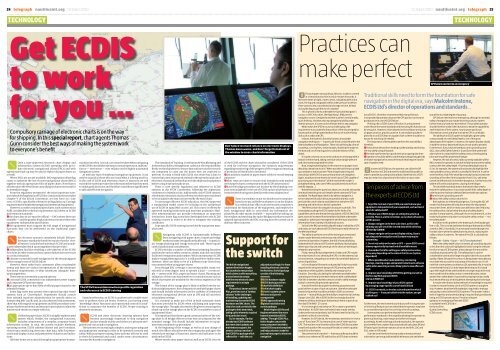

Don’t place too much reliance on electronic displays,<br />

Thomas Gunn warns, and don’t forget to look out of<br />

the window to cross-check information<br />

of the ECDIS and the charts should be considered. If the ECDIS<br />

is used for real-time navigation, the statutory requirements<br />

regarding monitoring of the progress of the voyage and marking<br />

of positions will need to be considered:<br />

zare positions marked in paper charts solely for record-keeping<br />

purposes<br />

zwhat steps are taken to ensure that intended tracks marked<br />

on the paper charts correspond with the ECDIS information<br />

zhave the bridge procedures set in place by the shipping company<br />

been adapted for the use of ECDIS and are all persons concerned<br />

with the navigation familiar with these adaptations<br />

O<br />

There is a tendency to put too much trust in computerbased<br />

systems and believe whatever is on the display.<br />

It is essential that officers do not become complacent,<br />

understand the limitations of the equipment, and employ the<br />

basic navigational skills to cross-check the information displayed<br />

by all other means available — especially by looking out<br />

the window and watching the radar! Bridge procedures must be<br />

adapted appropriately and ENC training must be carried out to<br />

alleviate these concerns.<br />

Support for<br />

the switch<br />

The British navigational<br />

systems firm Kelvin Hughes<br />

has launched a new product<br />

which claims to offer everything<br />

a vessel needs to comply<br />

with the new electronic chart<br />

requirements in a single<br />

package.<br />

The product, known as ECDIS<br />

Plus, promises users a ‘turnkey<br />

solution’ to the challenges<br />

of installing, updating and<br />

maintaining licences for ECDIS<br />

hardware and ENC charts. The<br />

idea is for each user to tailor the<br />

package to their own needs,<br />

taking up the elements required<br />

for a particular vessel.<br />

So, for example, if a ship<br />

already has ECDIS hardware<br />

but needs chart updates and<br />

maintenance support, the<br />

owners can buy a version of<br />

the ECDIS Plus package which<br />

reflects this — with the cost<br />

adjusted accordingly. For those<br />

installing electronic charts for<br />

the first time, the full package<br />

consists of the following<br />

elements:<br />

zECDIS hardware supply<br />

zECDIS backup provision<br />

zchart folio definition<br />

zinitial chart supply<br />

zChartCo update system<br />

zlicence and permit<br />

management<br />

zIMO approved training<br />

zglobal installation and<br />

service packages<br />

Kelvin Hughes CEO Russell<br />

Hughes welcomed the move<br />

towards mandatory ECDIS,<br />

adding: ‘Through ECDIS Plus,<br />

Kelvin Hughes can provide<br />

every component needed to<br />

make ECDIS easy and compliant<br />

and help customers make the<br />

journey from paper to electronic<br />

navigation.’<br />

Practices can<br />

make perfect<br />

Things happen very quickly at 28 knots. A cable is covered<br />

cin 13 seconds and a mile in only 2 minutes 9 seconds. It<br />

feels even faster at night, close to shore, navigating with only a<br />

chart, the log and a stopwatch whilst under pressure to deliver<br />

three consorts into a coordinated anchorage on time. At least<br />

during the day you get the use of a sextant!<br />

This is what it is like to undertake the Specialist Navigator’s<br />

course, or SPEC N for short, the Royal Navy’s (RN) premier<br />

navigation course. Designed to test the student’s mental maths,<br />

quick thinking, initiative and raw navigational ability under<br />

intense pressure, it is seen as the ultimate test for any navigator.<br />

What makes the SPEC N course so challenging is the<br />

requirement to accurately fix the position of the ship and predict<br />

future position at high speed without the use of modern fixing<br />

aids such as radar and GPS.<br />

Instead, the student is forced to harness all available<br />

navigation techniques — in particular those contained within the<br />

Admiralty Manual of Navigation. These include fixing by a line of<br />

soundings, running fixes, sextant angles, doubling the angle on<br />

the bow and use of bearing pairs to calculate distance off an<br />

object.<br />

It is quite common on course to conduct an anchorage with a<br />

sextant in either hand, taking a vertical sextant angle with one<br />

and a horizontal angle with the other.<br />

Now, imagine plotting fixes in this manner on a paper chart.<br />

Would you know how to do it When was the last time you picked<br />

up a sextant or station pointer Now imagine planning and<br />

executing it with ECDIS as your primary means of navigation.<br />

Again, would you know how to do it and is your ECDIS capable of<br />

processing such information (At the moment the reader is<br />

probably thinking, who cares Who actually needs to do this in<br />

real life anyway...)<br />

Notwithstanding the questions above, you may be asking why<br />

one would need to go to such lengths when radar and GPS are<br />

available. The Royal Navy needs to be able to navigate in a<br />

sensor-deprived situation because operational areas could<br />

preclude the use of radar to avoid detection and where GPS<br />

jamming and other sensor denial is prevalent.<br />

The RN must train its navigators to acquire such skills. This<br />

necessitates pushing the ECDIS system to the limits of its<br />

capabilities and is why the warfare equivalent of ECDIS (WECDIS)<br />

gives access to increased functionality to facilitate underwater<br />

navigation, waterspace management and the input of position<br />

information from a variety of traditional sources.<br />

So that’s the RN, but realistically with today’s reliability of GPS<br />

and radar, are such advanced ECDIS techniques really relevant in<br />

the Merchant Navy<br />

The ability to perform some of the techniques mentioned<br />

above may be deemed unnecessary and old fashioned for<br />

commercial operation. However, the skill of manually fixing<br />

independent of radar and GPS and the ability to clearly display<br />

where your ship can and cannot go on the chart are techniques<br />

relevant to any mariner.<br />

Firstly, manual fixing independent of radar and GPS may be<br />

the only means of cross-checking the GPS or in the extreme, but<br />

not uncommon, navigating in an area of an unreliable datum or<br />

sensor input failure.<br />

Let’s not forget all the work conducted by Trinity House with<br />

regards to the very present danger of GPS jamming and the<br />

importance of being able to identify and manage such a<br />

situation. Secondly, calculating the safe water available when<br />

operating to minimal under keel clearance with a safety depth<br />

that falls in between charted contours is vital to safely manage<br />

today’s commercially pressured operations.<br />

It would therefore be prudent to develop procedures and<br />

practice them in case of such an outcome. I therefore advocate<br />

two techniques that should be utilised in ECDIS as common<br />

practice — manual fixing and the ability to implement a Limiting<br />

Danger Line (LDL). We at ECDIS Ltd feel so strongly about the<br />

relevance of these techniques that we teach them as part of our<br />

five-day STCW IMO 1.27 course.<br />

It is not enough to rely solely on GPS or radar to provide fix<br />

information. An ECDIS does not have to have a radar overlay<br />

under performance standards, but if it does have this facility, it is<br />

prudent to utilise it in its entirety.<br />

However, for GPS denial, the mindset you need to be in is not a<br />

case of ‘if you lose GPS’ but very much a case of ‘when you lose<br />

GPS’. The mariner must therefore utilise the ECDIS like any other<br />

navaid and question the accuracy of the data in order to quality<br />

control the information.<br />

The premise here is twofold — that manual fixing should be<br />

used to cross-reference GPS and that loss of GPS does not mean<br />

Traditional skills need to form the foundation for safe<br />

navigation in the digital era, says Malcolm Instone,<br />

ECDIS Ltd’s director of operations and standards…<br />

loss of ECDIS. I therefore recommend that manual fixing is<br />

incorporated by operators to prove the GPS position correct and<br />

good practice in case of ECDIS failure.<br />

Plotting a fix in ECDIS (Lines of Position) is a requirement<br />

under the performance standards and executing this function can<br />

be very quick. However, it does depend on the software and just as<br />

on paper, practice, practice, practice. It can easily be quicker to<br />

plot a fix on an ECDIS than on a paper chart so there should be no<br />

excuse for not doing it if needed.<br />

The importance of being able to perform this task swiftly is<br />

threefold:<br />

zit should not detract from looking out the window and driving<br />

the ship safely using all navaids<br />

zthe task is performed as a quick check at an appropriate time<br />

zoperators should be able to comfortably manage long periods<br />

of relative navigation for areas of the world that require it and in<br />

case of sudden need.<br />

In event of GPS failure, the operator can utilise the DR<br />

cfunction in ECDIS and revert to traditional fixing skills in<br />

order to provide accurate positional data. Note that loss of GPS<br />

may also mean loss of positional information on your radar.<br />

Ten pieces of advice from<br />

the experts at ECDIS Ltd<br />

1. To get the most out of your ECDIS you need to know your<br />

equipment. Ask questions of your equipment, such as Does it<br />

alarm for safety depth<br />

2. Effective use of ECDIS hinges on setting the system up<br />

correctly. There is a lot to remember, so use check-off cards to<br />

aid this process<br />

3. Always navigate on the best scale chart, as this is the<br />

only way you will see all the charted data whilst not being<br />

affected by SCAMIN<br />

4. Always navigate on the correct display setting. Base is<br />

not adequate for navigation and Standard may require<br />

customising<br />

5. Do not rely solely on the radar or GPS — prove ECDIS correct<br />

at every opportunity by visual and all available means<br />

6. Remember that after setting your safety contour value,<br />

it may vary depending on the scale of chart in use (system<br />

dependent)<br />

7. Where possible when route planning, use clearing<br />

bearings, clearing ranges and parallel index lines to enhance<br />

safety when executing a route. Many systems now offer such<br />

tools<br />

8. Improve your knowledge of ECDIS by getting yourself on<br />

the five-day MCA approved ECDIS<br />

course at ECDIS Ltd<br />

9. Improve your knowledge of your ECDIS system<br />

by arranging a type-specific course from ECDIS Ltd<br />

10. ECDIS is a navaid, so treat as such and question what it<br />

is telling you — if you put rubbish into the system, you get<br />

rubbish out!<br />

Furthermore, the environment you find yourself in may preclude<br />

or limit visual fixing to such an extent that the operator may have<br />

to use transferred position lines or fix by a line of soundings.<br />

Some systems can perform beyond the minimum<br />

performance standards in this regard by allowing the operator to<br />

plot visual bearings, radar ranges and other techniques<br />

accordingly. As well as being quick and easy to plot, the operator<br />

also benefits from a system that automatically calculates DR and<br />

EP based upon last known values such as set and drift, COG and<br />

SOG, when in ‘DR mode’.<br />

It can be seen therefore that manually entered positional<br />

information can very quickly establish where you are and where<br />

‘GPS failure need not be an emergency’<br />

you will be to a high degree of accuracy.<br />

GPS failure need not be an emergency, although to maintain<br />

safety of navigation you may be forced to push your system<br />

further than you have ever done before. The prudent operator<br />

should therefore make it their business to know the capabilities<br />

and limitations of their system, how to prove positional<br />

information correct and what to do when GPS is unreliable.<br />

The ability of an ECDIS system to highlight a given safety<br />

contour based on a set Safety Depth is one of the great<br />

advantages of the system. In essence, the system displays clearly<br />

in bold the contour beyond which you do not wish to proceed.<br />

Furthermore, if you have activated your anti-grounding cone<br />

(AGC, also called Safety Frame or Guard Zone) the system will<br />

alarm when in contact with the safety contour, thereby giving<br />

prior warning of the proximity of danger.<br />

However, the lack of contour data currently available within<br />

ENCs means the operator is not able to fully harmonise the safety<br />

contour with the safety depth. If I set my safety depth value to<br />

6.5m, for example, the system will automatically highlight the<br />

next available contour, which is normally the 10m line. It can be<br />

seen therefore, that if the vessel by necessity has to proceed over<br />

soundings of less than 10m but greater than 6.5m, safe areas<br />

cannot be defined and it is therefore dangerous. Furthermore, the<br />

system will continuously alarm, causing alarm fatigue.<br />

This shortfall essentially means that vessels that need to<br />

reduce the safety contour in accordance with their safety depth in<br />

order to get into harbour safely will be faced with two options:<br />

zturn the anti-grounding cone off<br />

zreduce the safety contour value to 5m<br />

Both options are inherently dangerous. Turning the AGC off<br />

means that the system will only alarm when the ship symbol<br />

encounters them, which in most cases will be too late. Reducing<br />

the safety contour value below the value of safety depth is<br />

possible in many systems, although I do not recommend it, as the<br />

majority of systems only alarm crossing the safety contour — not<br />

the safety depth!<br />

A solution to this problem is the drawing of a limiting danger<br />

line or LDL. This is a tried and tested technique that works on RNCs<br />

as well as ENCs. Essentially, it is a manually inserted danger line<br />

that will alarm when the safety frame touches it, replacing the<br />

safety contour in extremis. The value of the LDL is calculated as<br />

follows:<br />

Draught + Safety + Squat — HoT (Time dependent)<br />

When the safety depth value is inserted, all soundings equal to<br />

or less than this value are highlighted in bold. Using the relevant<br />

function on your ECDIS system, draw a danger line around the<br />

soundings to produce the LDL. The safety value is a prime<br />

consideration and must be large enough to take into account the<br />

quality of data. Because the contour is being drawn manually you<br />

must take into account the inaccuracy of the data in use. It is of<br />

note that some systems can draw an LDL automatically. It must be<br />

remembered that a LDL is time dependent because it is based<br />

upon the height of tide and that when no longer required it must<br />

be ensured that the safety contour is reverted back to a value<br />

greater than safety depth. It goes without saying that you really<br />

must know what you are doing before attempting this technique.<br />

It may be seen that an advanced level of knowledge is required<br />

in order to ensure the best use of an ECDIS system on any given<br />

ship. However, what level of knowledge is required to manage<br />

and quality control a fleet of ECDIS systems The answer is that a<br />

level of expertise and understanding is required that goes beyond<br />

being an ECDIS operator at sea. Provision of expert<br />

guidance on managing a fleet with ECDIS<br />

is available from ECDIS Ltd in<br />

the form of the<br />

Quality Controlling<br />

ECDIS course.