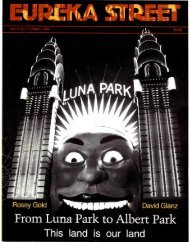

Shane Malone - Eureka Street

Shane Malone - Eureka Street

Shane Malone - Eureka Street

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Well, Poland is almost judenftei.<br />

Richmond, in his pilgrimage through<br />

Poland to Konin, visits town after<br />

town, village after village, where his<br />

family contacts had lived and where<br />

old and often large Jewish communities<br />

had been. Now there are none<br />

there, except for one or two old Jews,<br />

bewildered, as if in a dream . The<br />

m ajority had been killed, the survivors<br />

fl ed-to Israel, or America or<br />

Australia, as from a plague spot.<br />

There are many synagogues and Jewish<br />

houses restored. But they are<br />

museums. No Jews.<br />

Along Richmond's journey, even the cemeteries had<br />

disappeared, and when he got to Konin, he had to search<br />

befme finding a little stone memorial, deep in the forest,<br />

put up by a few people, near the mass graves. There is a<br />

detailed account of the Konin massacre, given by a Polish<br />

vet, who was forced to observe it and dispose of the bodies.<br />

I think it is the most terrible thing I have ever read.<br />

I went to Cra cow in 1990 with a<br />

friend, whose home town it had been.<br />

Cracow in '39 had 200,000 people,<br />

with perhaps 70,000 Jews. Now there<br />

arc 800,00 inhabitants- in from the<br />

country-and 500 Jews. Synagogues,<br />

cemeteries and the Jewish quarter<br />

were being restored but for America<br />

n tourists. Along Richmond's journ<br />

ey, even the cemeteries had<br />

disappeared, and when he got to<br />

Konin, where every Jew there and<br />

thereabouts had been murdered, he<br />

had to search before finding a little<br />

stone memorial, deep in the forest,<br />

put up by a few people, near the mass<br />

graves. There is a detailed account in<br />

this book of the Konin massacre,<br />

given by a Polish vet, who was forced,<br />

along with a few others, to observe it<br />

and dispose of the bodi es. I think it is<br />

the most terrible thing I have ever<br />

read.<br />

But to restart, at Verstandig's<br />

childhood. He gives a simultaneously<br />

delightful yet sombre account of<br />

growing up in a shteLl, and the boring<br />

nature of the religious and secular<br />

education he received-all rote<br />

learning and the cane. There were<br />

the family politics and the marriage<br />

market, with the family the eco-<br />

nomic institution that Marx thought<br />

it was. Class and status distinctions<br />

were alive and well- one didn't recognise<br />

poor relatives. The stories of<br />

the clmorret (beggar) with a place at<br />

the end of the rich man's table were<br />

true, but hardly a picture oft he harsh<br />

economic and social realities of Jewish<br />

Poland. Verstandig estimates as<br />

many as 90 per cent of the shtetl<br />

youth as being unemployed. So<br />

people went around singing 'If I were<br />

a Rothschild, diddle diddle diddle<br />

dum'. Fans of Fiddlet on the Roof<br />

please n ote. Young Verstandig,<br />

trained as a lawyer,<br />

had lots of chutzpa,<br />

which hasn ' t deserted<br />

him, and was<br />

doing well, until the<br />

roof fell in and the<br />

world stopped. His<br />

chronicle at this<br />

point is enthralling<br />

and frightening.<br />

In contrast, Richm<br />

ond builds block<br />

by block, by endless<br />

stories of peoples's<br />

lives and the deaths<br />

of villages and towns, whole fa milies,<br />

a whole people. Both writers<br />

tell of num erou s rescuers and<br />

kindnesses, and great bravery by<br />

Polish people-often quite unexpected<br />

and very often by the simple<br />

and the simply religious. Richmond,<br />

whose book is adorned with photographs<br />

of families long since gone<br />

and scen es long swept away, found<br />

some of the Polish friends and protectors<br />

who were astonished to hear<br />

of people whom they hadn't known<br />

since the war- along with their<br />

subsequent fates. It is all desperately<br />

sad, and one of the low<br />

"'\ T points in human history.<br />

v ERSTANDIG RAI SES SOME interesting<br />

queries about the Allies and<br />

Auschwitz. At one point, when in<br />

hiding, near what was becoming the<br />

front line as the Red Army advanced,<br />

his group noticed the flights of fourengined<br />

bombers pounding the German<br />

lines in support of the Russians.<br />

These they eventually identified as<br />

American bombers operating from a<br />

base in Ukraine. They were working<br />

on a long line north-south in Poland.<br />

On this line was Auschwitz. Ye t we<br />

are still told that that camp and even<br />

its railway lines were too far for<br />

planes to get at. It might have been<br />

from the West- but the East<br />

T he author is scornful of the<br />

Allies' practical indifference to the<br />

fate of Europe's Jews, an indifference<br />

shared by the Jewish World Congress<br />

based in America. He asserts that<br />

this indifference continued after the<br />

war with the displaced persons, of<br />

whom he was one in Germany, still<br />

neglected and starving long after<br />

war's encl. The great sums raised in<br />

America just mel ted away, the DPs<br />

on the spot ge tting little. Some of<br />

my friends say it was similar in<br />

Poland. Scams from top to bottom.<br />

Vcrstanclig threw himself in to<br />

communal politics here, but after<br />

19 72 cl ecicle cl that they were<br />

irrelevant to the present day, that<br />

they were still preoccupied with old<br />

issues and divisions, and leadership<br />

changes were altering the whole<br />

character of what was, in any case,<br />

ceasing to be a community. So he<br />

withdrew and m oved over<br />

to charitable work.<br />

R<br />

I CI~M ON D' S 1\00K is not political<br />

in the sam e way. He lets his<br />

interviewees tell their own stories,<br />

so yo u get a broader perspective on a<br />

world that is gone, leaving a strange<br />

pall hanging over the landsca pe,<br />

while the people below go about their<br />

business as though nothing has ever<br />

happened. But of course life must go<br />

on, must renew itself. A condition of<br />

permanent mourning, which I see in<br />

many people, is living death. But<br />

you can't always choose your mental<br />

state.<br />

Richmond finishes:<br />

From the beginning I had known I<br />

would have to co me here. Now the<br />

journey was done. To say I felt regret<br />

at leaving this place would be false<br />

and sentimental. I felt no emotion,<br />

ma ybe it was spent. Or may be th e<br />

town was releasing me from its grip,<br />

for I knew now that it was not the<br />

pl ace that held meaning for me but<br />

the people who once lived here.<br />

Their Konin would stay with me<br />

always, a persistent echo.<br />

Mark Verstanclig would say<br />

Amen to that.<br />

•<br />

Max Teichmann is a Melbourne<br />

writer and reviewer.<br />

36<br />

EUREKA STREET • APRI L 1996