You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

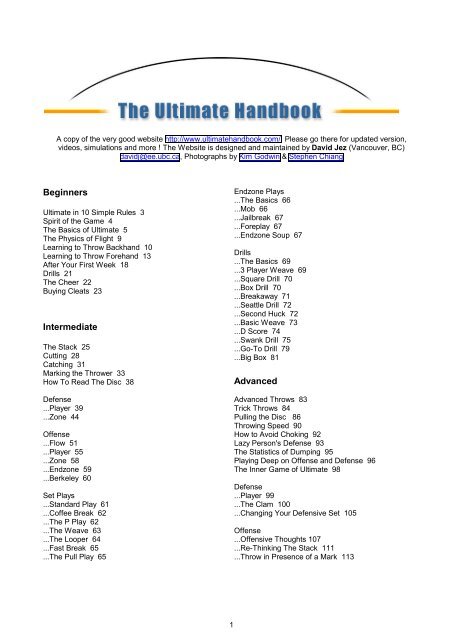

A copy of the very good website http://www.ultimatehandbook.com/. Please go there for updated version,<br />

videos, simulations and more ! The Website is designed and maintained by David Jez (Vancouver, BC)<br />

davidj@ee.ubc.ca, Photographs by Kim Godwin & Stephen Chiang<br />

Beginners<br />

Ultimate in 10 Simple <strong>Rules</strong> 3<br />

Spirit of the Game 4<br />

The Basics of Ultimate 5<br />

The Physics of Flight 9<br />

Learning to Throw Backhand 10<br />

Learning to Throw Forehand 13<br />

After Your First Week 18<br />

Drills 21<br />

The Cheer 22<br />

Buying Cleats 23<br />

Intermediate<br />

The Stack 25<br />

Cutting 28<br />

Catching 31<br />

Marking the Thrower 33<br />

How To Read The Disc 38<br />

Defense<br />

...Player 39<br />

...Zone 44<br />

Offense<br />

...Flow 51<br />

...Player 55<br />

...Zone 58<br />

...Endzone 59<br />

...Berkeley 60<br />

Set Plays<br />

...Standard Play 61<br />

...Coffee Break 62<br />

...The P Play 62<br />

...The Weave 63<br />

...The Looper 64<br />

...Fast Break 65<br />

...The Pull Play 65<br />

Endzone Plays<br />

...The Basics 66<br />

...Mob 66<br />

...Jailbreak 67<br />

...Foreplay 67<br />

...Endzone Soup 67<br />

Drills<br />

...The Basics 69<br />

...3 Player Weave 69<br />

...Square Drill 70<br />

...Box Drill 70<br />

...Breakaway 71<br />

...Seattle Drill 72<br />

...Second Huck 72<br />

...Basic Weave 73<br />

...D Score 74<br />

...Swank Drill 75<br />

...Go-To Drill 79<br />

...Big Box 81<br />

Advanced<br />

Advanced Throws 83<br />

Trick Throws 84<br />

Pulling the Disc 86<br />

Throwing Speed 90<br />

How to Avoid Choking 92<br />

Lazy Person's Defense 93<br />

The Statistics of Dumping 95<br />

Playing Deep on Offense and Defense 96<br />

The Inner Game of Ultimate 98<br />

Defense<br />

...Player 99<br />

...The Clam 100<br />

...Changing Your Defensive Set 105<br />

Offense<br />

...Offensive Thoughts 107<br />

...Re-Thinking The Stack 111<br />

...Throw in Presence of a Mark 113<br />

1

This word document was assembled by Bernhard Frötschl (Berlin) with<br />

help from Roman Gerlach, Lars Wolter and Max Mönch in May 2001.<br />

Print it double sided, 2 pages on 1, so you get 63 handy pages!<br />

Drills<br />

...Triple Box 117<br />

...Uphill Scrimmage 119<br />

...Fast Break 121<br />

History<br />

Where the Frisbee First Flew 123<br />

The History of Ultimate 125<br />

<strong>Official</strong> <strong>Rules</strong><br />

UPA 132<br />

WFDF 149<br />

Callahan 165<br />

Captains<br />

How to Start a Team 175<br />

Playing In Tournaments 176<br />

Tournament Organization 177<br />

Basic Stretches 195<br />

Active Isolated Stretching 196<br />

Twist & Stretch 197<br />

Mobility Program 199<br />

ACL Prevention 204<br />

Yoga & Athleticism 207<br />

Nutrition<br />

Top 10 Foods 208<br />

Fluid Intake 209<br />

The Role of Meat 212<br />

Vegetable Matter 217<br />

Nutritional Program 219<br />

For Women Only 222<br />

Brain Drain 225<br />

Game Day 227<br />

Training<br />

Strength Training 229<br />

Improving Your Vertical Leap 232<br />

Hot Stuff<br />

The Ten Commandments Of the Disc 185<br />

Top Ten Rule Changes ... 186<br />

Top Ten Reasons Why ... 186<br />

Snap Krackle Pop - No Frisbee 186<br />

Disc Drive 187<br />

More Than a Simple Fling: Ultimate Frisbee 188<br />

Ultimate Frisbee Tests Character, Fitness 190<br />

Ultimate Frisbee Gets Down and Down 191<br />

Injuries<br />

Ankle Advice 239<br />

Injury Prevention 242<br />

R.I.C.E. 244<br />

Shin Splints 245<br />

Down But Not Out 246<br />

Links 250<br />

Stretching<br />

Glossary 251<br />

Warming Up 194<br />

2

Beginners<br />

Ultimate in 10 Simple <strong>Rules</strong><br />

1. The Field — A rectangular shape with endzones at each end. A regulation field is 70 yards by 40 yards, with<br />

endzones 25 yards deep.<br />

2. Initiate Play — Each point begins with both teams lining up on the front of their respective endzone line. The<br />

defense throws („pulls“) the disc to the offense. A regulation game has seven players per team.<br />

3. Scoring — Each time the offense completes a pass in the defense‘s endzone, the offense scores a point.<br />

Play is initiated after each score.<br />

4. Movement of the Disc — The disc may be advanced in any direction by completing a pass to a teammate.<br />

Players may not run with the disc. The person with the disc („thrower“) has ten seconds to throw the disc.<br />

The defender guarding the thrower („marker“) counts out the stall count.<br />

5. Change of possession — When a pass in not completed (e.g. out of bounds, drop, block, interception), the<br />

defense immediately takes possession of the disc and becomes the offense.<br />

6. Substitutions — Players not in the game may replace players in the game after a score and during an injury<br />

timeout.<br />

7. Non-contact — No physical contact is allowed between players. Picks and screens are also prohibited. A<br />

foul occurs when contact is made.<br />

8. Fouls — When a player initiates contact on another player a foul occurs. When a foul disrupts possession,<br />

the play resumes as if the possession was retained. If the player committing the foul disagrees with the foul<br />

call, the play is redone.<br />

9. Self-Refereeing — Players are responsible for their own foul and line calls. Players resolve their own<br />

disputes.<br />

10. Spirit of the Game — Ultimate stresses sportsmanship and fair play. Competitive play is encouraged, but<br />

never at the expense of respect between players, adherence to the rules, and the basic joy of play.<br />

References<br />

http://www.cs.rochester.edu/u/ferguson/ultimate/ultimate-simple.html<br />

3

Spirit of the Game<br />

„Spirit of the Game“, perhaps the central governing principle of ultimate. Ultimate players, by their own<br />

reckoning, are among the more courtly athletes. Respect for one‘s opponent is paramount. In contrast to<br />

crybaby sports like soccer and basketball wherein skilled thespians refine the art of fouling and being fouled, the<br />

official ultimate rules strictly forbid any action—taunting, intentional fouls—that might be construed as bad<br />

sportsmanship. „Often,“ says the introduction to the rules, „a player is in a position where it is clearly to the<br />

player‘s advantage to foul“ or rattle his opponent with taunts, but such tactics are considered „a gross offense<br />

against the spirit of sportsmanship.“ Dennis Rodman, stay right where you are.<br />

The most compelling aspect of ultimate is the absence of penalties. In the preface to the rules, the founding<br />

fathers of the sport, such trusting souls, „assumed that no ultimate player will intentionally violate the rules; thus<br />

there are no harsh penalties for inadvertent infractions.“ (In fact, there really aren‘t any penalties at all.) This<br />

statement is, in its off-hand way, revolutionary. Imagine a country with no way to enforce its laws other than<br />

simply by presuming its citizens would never intentionally violate the law in the first place. Foolish? Naïve? In<br />

ultimate-land, it works.<br />

Should some vicious churl choose to flout the Spirit of the Game, the founding fathers conceived of a simple<br />

safeguard. In place of referees, the players call their own fouls. For instance, if Jane hacks Mary while Mary is<br />

winding up to deliver the huck to end all hucks, Mary simply yells „foul,“ and it‘s a foul. Jane is presumed to have<br />

hacked unintentionally, and play resumes with Mary‘s possession. Since players cannot „foul out,“ a cynic might<br />

think it a toothless sort of foul call, but the Spirit so dominates the sport as to make further disciplinary measures<br />

unnecessary.<br />

In Ultimate, every player is responsible for their own conduct on the field. There‘s no refs to make sure that<br />

everyone acts like grown-ups, so it‘s the responsibility of players to call fouls on themselves if the person they<br />

have fouled does not call the infraction. That‘s right. You can call a foul on yourself. Ultimate relies on the<br />

honour system and the belief that no one will intentionally cheat, much like marriages, the income tax system,<br />

and all-you-can-eat sushi bars. [1]<br />

Ultimate‘s rules, like any sport‘s, can take a while to learn. However, they can, for the most part, be summed up<br />

by the concept of „Spirit.“ Highly competitive play is encouraged, but never at the expense of mutual respect<br />

between players, adherence to the agreed-upon rules of the game or the basic joy of play. The purpose of the<br />

rules of Ultimate is to provide a guideline which describes the way the game is played. It is assumed that no<br />

Ultimate player will intentionally violate the rules; there are no harsh penalties for inadvertent infractions but,<br />

rather, a method for resuming play in a manner which simulated what would most likely have occurred had there<br />

been no infraction. It couldn‘t be much simpler. Spirit allows the game to be played without refs, without<br />

untoward aggression, and without long stoppages in play. It really can‘t be stressed too much. Spirit is what<br />

makes Ultimate so much fun. If you can‘t relate to the concept of Spirit you might be better off trying a different<br />

activity; such as sitting in a darkened room cleaning your firearms and obsessing over conspiracy theories. [2]<br />

References<br />

[1] Mark Schulte, http://www.virginiadynamics.com/ultimate.htm<br />

[2] Vancouver Ultimate League, http://www.vul.bc.ca/<br />

4

The Basics of Ultimate<br />

Who catches a disc better than anyone? Dogs. And they don‘t even have thumbs. It goes to show, a long<br />

history of taking part in team sports and being a jock isn‘t necessary to be an Ultimate player. As even the<br />

briefest exposure to the game demonstrates, running, throwing, and catching are the key physical skills that<br />

make a good Ultimate player. An understanding of strategy and positioning are the most important mental<br />

aspects of the game.<br />

Both sides of the game can be learned easily with practice. The best way to gain those skills is through<br />

exposure to the game. Taking the opportunity to join pick-up games often means getting to play with some<br />

experienced players. Some cities will even offer skills clinics which is an invaluable way to receive top-notch<br />

coaching.<br />

Running<br />

A disc is like a pair of scissors. You‘re not supposed to run with either. There‘s still a lot of running in Ultimate<br />

however. So, don‘t blame anyone if you start feeling fitter and your clothes are getting baggy.<br />

Offensive players are constantly on the look out for open areas to provide the thrower, known as the „handler“,<br />

with targets. This means sudden changes in direction, speed and angle - „cuts“ - to break away from their check<br />

(i.e. the defensive player covering them). Defensive players are reacting to those cuts and anticipating the next<br />

move. When on offense try and think ahead and plan your cuts. If you find one that works against a particular<br />

check, don‘t be afraid to exploit it a few times until they catch on. When on defense try to anticipate where your<br />

check might go so you can prevent, intercept, or block the throw.<br />

Unlike other sports, particularly basketball, you cannot use any other player on the field to impede the progress<br />

of your check. This is called a „pick“. This rule is designed to prevent injuries. Even an unintentional pick can<br />

result in high-speed collisions between players. It‘s of the utmost importance to make sure that everyone on<br />

your team knows how to spot and avoid picks.<br />

One of the reasons there‘s a lot of running in Ultimate is that „turnovers“ occur. This means that during the<br />

course of uninterupted play you may switch from being on offense to defense a number of times. When a<br />

turnover occurs, yell „Turnover“ or „TO“ nice and loud so that the rest of your team can change from offense to<br />

defense quickly. If you are on offense when the turnover occurs and you are unsure where to go - just stick with<br />

whoever is checking you. Also make sure that there are at least as many players from your team as your<br />

opponents‘ between you and your end zone. If not, fall back and check the unguarded player closest to the<br />

endzone. A simple way to remember this is with the following phrase: „always take the runner“ (unguarded<br />

player).<br />

Throwing<br />

There are more ways to throw a disc than you ever imagined. A general rule of thumb is: the sillier the name of<br />

the throw - the stranger the technique required. Most of the time, however, you will rely on three kinds: the<br />

forehand of „flick“, the backhand, and hammer. The backhand is the throw everybody used since day one to<br />

chuck a disc around on the beach. The hammer is an upside-down forehand. The forehand is the most<br />

improbably combination of physics and goofy body language ever invented. After about a million throws you‘ll<br />

start to feel like you don‘t look somewhat silly when you throw a forehand. Don‘t get your hopes up.<br />

5

However, long before then you‘ll have developed a forehand throw that actually works. Remember that spin is<br />

the most important factor in a disc‘s flight and try a lot of different, subtle variations. Everybody‘s got their<br />

favourite tip or technique which they will be more than happy to share. Ask around and find out what works for<br />

you.<br />

Catching<br />

For most catches below your shoulder and above your knees the „pancake“ catch is your best bet. Simply trap<br />

the disc between your palms when it approaches. For more extreme situations two or one-handed rim catches<br />

are required. Try to practice one-handed and wrong-handed catches when warming up or doing drills so that<br />

you are always improving your hand/eye coordination.<br />

Remember to watch the disc all the way into your hands and make sure you have caught it before turning and<br />

looking for the next receiver. Another important pointer is to never give up on a disc. Catches that seem<br />

improbably are often quite catchable if they start to hand in the air due to wind or flight angle.<br />

However, do not crash into other players in an attempt to perform a leaping catch. A rule called the „principle of<br />

verticality“ stipulated that each player is entitled to the space above his body. Nor can you hipcheck another<br />

player or hold them down to prevent them from jumping up to catch the disc. Anything beyond the most<br />

incedental contact between players is a foul in Ultimate (unless there‘s tickling involved).<br />

What Happens During a Game<br />

Captains from each team flip a disc simultaneously. A captain or third player calls „Same“ or „Different“ before<br />

the discs hit the ground. If the player‘s call is correct then his/her team has the choice to throw or receive the<br />

first „pull“, or to choose which end zone they would like to defend for the first point. Generally speaking,<br />

choosing to receive the pull is the most logical choice. The team which loses the flip takes the remaining option.<br />

Each team lines up seven players on their respective goal line. The pulling team must stay on or behind their<br />

goal line until the pull occurs. The receiving team must stand on the goal line and maintain their positions<br />

relative to each other until the pull is thrown - to make it easier for each member of the pulling team to figure out<br />

who they will check. If you hear the call „Hold your line“ it means that a receiving team is shifting positions on<br />

the line prior to the pull.<br />

6

When the pulling team is ready to begin play, the puller holds the disc above his/her head. When a member of<br />

the receiving team holds their hand above their head to signal readiness, the pull can be thrown.<br />

So, everyboday is in position, smiling, and ready to go. The pull is thrown, the disc sails gracefully towards the<br />

other end zone - a shining miracle of aerodynamics - and the pulling team runs down the field to pick up their<br />

checks and another game of Ultimate is underway. Now the fun really begins.<br />

On the pull, the receiving team does not have to catch the disc to take possession. It can simply be allowed to<br />

land. However, whoever touches the disc first ( either by catching it or picking it up from the ground) must be the<br />

first handler. Usually a receiving team will designate a player to be the handler before the pull, to minimize<br />

confusion. If the disc hits the ground and begins rolling, any player on the receiving team can stop its progress<br />

without having to become the handler.<br />

Because you can‘t run with the disc once caught, players must establish a pivot foot when they are in<br />

possession of the disc. Usually, if you are right-handed it will be your left foot, and vice versa for lefties. You<br />

can‘t drag or lift your foot until you have thrown the disc. If you do so, it‘s a „travelling“ violating.<br />

Unless you are very confident that you‘re going to catch it, let the disc hit the ground. This is very, very<br />

important! If you try and catch the disc, and fail, bobbling the disc and dropping it, then a turnover occurs<br />

(usually just a few meters from your end zone). Which wouldn‘t be so bad if not for the fact that every person<br />

who saw the event will probably mock you mercilessly, your team will be a tad disappointed, and you‘ll have to<br />

think up a lame excuse on short notice. You have been warned!<br />

In the event that the disc flies out of bounds and is caught before touching the ground, the receiving team must<br />

begin on the sideline at the point where the disc went out of bounds.<br />

If the disc flies out of bounds and last the most common choice is invoke the „Middle“ rule. This means that<br />

before the disc hits the ground someone from the receiving team raises his arm and calls „Middle“. This allows<br />

the receiving team to begin play in the middle of the field at the point where the disc crossed the sideline.<br />

If the disc lands in the end zone, then the receiving team can begin play immediately from within the endzone,<br />

or walk the disc to the goal line, touch it to the ground, and begin play from that point. You cannot decide to<br />

begin play from the goal line, and then change your mind and throw the disc prior to reaching the goal line.<br />

If the disc remains airborne and flies out the back of the endzone, it is considered a „Brick“ and play is initiated<br />

in the middle of the field, three meters forward of the goal line.<br />

After the initial pull the receiving team becomes the offense. The offense will usually try to form „stack“. When<br />

you first begin playing, a stack will seem far too pre-meditated and the best option will seem like running willynilly<br />

around the field. The sooner your team can shake themselves of this misapprehension the better. Scrambly<br />

play may seem to work at the beginner level, but it will quickly prove ineffective against more experienced<br />

teams.<br />

When forming a stack the offensive players should get to the stack as quickly as possible, form a straight line<br />

between the thrower and the opponents‘ end zone, and take their rest in the stack rather than jogging to the<br />

stack. This reduces „clogging“. Clogging is a situation where potential receivers are stationary and occupying<br />

the „flat“ (an open area where the thrower could complete a pass to them).<br />

Generally, one side of the field will be open to receivers because the person checking the thrower, the „marker“<br />

is „forcing“ (favouring one side of the thrower to force them to throw to one area of the field) as he/she calls out<br />

the „stall count“. As a rule, try to decide which side your team will force to (usually designated as „home“ or<br />

7

„away“) for the duration of the point so that your players can anticipate where to mark if their player catches the<br />

disc, and what area to guard when their check is cutting for a pass.<br />

The marker counts (at one second intervals) „Stall one, Stall two, ... up to „Stall Ten“. If the marker reached Stall<br />

Ten (as soon as he/she begins to speak the word) before the thrower initiates the pass then a turnover occurs.<br />

A fast count is not only against the rules, it‘s very tacky. And who wants to be tacky? In the event of a fast count<br />

by the thrower, two seconds are deducted from the count and play is continued without interruption. A second<br />

fast count call results in a foul. The disc is checked and the count is reset to zero.<br />

The key points for marking are: the marker must be closer than three meters (before initiating the stall count) but<br />

no less than one disc width from the thrower, they cannot straddle the thrower‘s pivot foot, and they cannot<br />

prevent the thrower from pivoting. Only one person can mark the handler at any one time.<br />

In a perfect world, the handler completes his pass, runs to take his position in the stack, and the process<br />

repeats as many times as necessary to get to the end zone and score. Usually, however, there will be a<br />

turnover before a point is scored and it‘s time to switch from offense to defense, or vice versa. Once a point is<br />

scored, the teams swap ends and the scoring team pulls to restart play.<br />

How to Score<br />

To gain points in an Ultimate game you have to have a member of your team catch the disc in the „end zone“. If<br />

you‘re close to the end zone and you catch the disc... Stop! If your team-mates are yelling at you to „Check<br />

Feet!“ you‘re probably in the end-zone. The reason for their insistence if that if you pass the disc inside the end<br />

zone, and the receiver fails to catch the disc, no points are scored and a turnover occurs.<br />

If you decide that you are outisde the end zone, continue play. If your are in the end zone, stop play and<br />

prepare to smile graciously as everyone compliments you on your skill, luck, timing, good looks, or combination<br />

thereof. If you catch the disc, and your momentum carries you into the end zone, go back to the place where<br />

you caught the disc and resume play. You cannot intentially tip or deflect the disc forward into the end zone (or<br />

any part of the field for that matter) and then catch it, although unintentional bobbling to control and catchthe<br />

disc is allowed.<br />

When a point is scored, it is the only time during the regular play that substitutions can occur, unless the<br />

substitution is to replace an injured player. You can’t change the line on the fly as in hockey or when a time-out<br />

is called.<br />

So that‘s Ultimate in a nutshell. It‘s about fun, friends, and chasing a piece of flying molded plastic around the<br />

sky until your tongue is dragging on the field—just so that you can make up a song about the whole experience.<br />

References<br />

The Vancouver Ultimate League, http://www.vul.bc.ca<br />

8

The Physics of Flight<br />

Forward flight splits rushing air at the disk‘s leading edge: half goes over the Frisbee; half goes under. Because<br />

the edge is tipped up, the disk deflects the lower airstream downward. As the Frisbee pushes down on the air,<br />

the air pushes upward on the Frisbee—a force known as aerodynamic lift. The upper airstream is also deflected<br />

downward. Like all viscous fluids, flowing air tends to follow curving surfaces—even when those surfaces bend<br />

away from the airstream. The inward bend of the upper airstream is accompanied by a substantial drop in air<br />

pressure just above the Frisbee, sucking it upward (Bernoulli effect). These two forces taken together tend to<br />

LIFT the Frisbee against gravity.<br />

Limits to the airstream‘s ability to follow a surface explain why a Frisbee flies so poorly upside down. When the<br />

upper airstream tries to follow the sharp curve of an inverted Frisbee‘s hand grip, its inertia breaks it away from<br />

the surface. A swirling air pocket forms behind the Frisbee and destroys the suction, raising the air resistance.<br />

Once this air resistance has sapped the inverted disk‘s forward momentum, it drops like a rock. Players can<br />

take advantage of this effect in a hard-to-catch throw called the hammer.<br />

Rotation is crucial. Without it, even an upright Frisbee would flutter and tumble like a falling leaf, because the<br />

aerodynamic forces aren‘t perfectly centered. Indeed, the lift is often slightly stronger on the forward half of the<br />

Frisbee, and so that half usually rises, causing the Frisbee to flip over. A spinning Frisbee, though, can maintain<br />

its orientation for a long time because it has angular momentum, which dramatically changes the way it<br />

responds to aerodynamic twists, or torques. The careful design of the Frisbee places its lift almost perfectly at<br />

its center. The disk is thicker at its edges, maximizing its angular momentum when it spins. And the tiny ridges<br />

on the Frisbee‘s top surface introduce microscopic turbulence into the layer of air just above the label. Oddly<br />

enough, this turbulence helps to keep the upper airstream attached to the Frisbee, thereby allowing it to travel<br />

farther.<br />

References<br />

Louis A. Bloomfield Professor of Physics, University of Virginia Author of How Things Work: The Physics of<br />

Everyday Life, http://www.scientificamerican.com/1999/0499issue/0499working.html<br />

9

Learning to Throw Backhand<br />

There are two main factors to consider when throwing a disc; forward momentum and centrifugal force (spin). In<br />

other words, a well-thrown disc will have both sufficient wrist „snap“ AND force behind it. Wrist snap is often<br />

overlooked by novices, but is essential to throwing the disc successfully.<br />

Two additional important considerations are the angle to the ground at which the disc is released, and the point<br />

in the throw at which the disc is released. If this all sounds confusing, don‘t worry too much. With disc in hand,<br />

your physical instincts will kick in and grasp the mechanics fairly quickly.<br />

Just as in tennis, there are two main throws: the forehand (aka flick) and the backhand. If you‘ve thrown around<br />

with your friends, you have probably been throwing backhands. Here is some useful advice on this throw.<br />

The Backhand<br />

...The Basic Grip<br />

Shown are a couple of different versions of this grip. It is characterised by the index finger of the throwing hand<br />

being placed along the outside rim of the disc.<br />

The first version has the middle finger of the throwing hand extended towards the center of the disc. This<br />

version gives a high degree of control and stability, since the index finger along the rim helps with direction and<br />

the middle finger supporting the disc supplies stability.<br />

On the down side, there are only two fingers gripping the rim, and this leads to much less power than most of<br />

the other grips. Most of the power in a grip comes from the ripping of the disc off the end of the index finger.<br />

The second version is one rarely seen. It has the index finger on the rim but not the middle finger support. It<br />

gives a little more power as more fingers are gripping the rim, but the power gain is fairly insignificant compared<br />

to the loss of control. Bigger power gains are obtained by having the index finger gripping the rim.<br />

...The Power Grip<br />

This is the most popular grip among experienced throwers, and is the one used by almost all disc golfers. All<br />

fingers are gripping the rim tightly, and there are no fingers supporting the disc.<br />

This means there is a considerable loss of control, since the release point is much harder to judge. A fair degree<br />

of control can be regained through practice, and the loss is offset in some ways by the large power gain<br />

10

produced by the disc ripping off the end of the index finger. This grip does however make it harder to throw the<br />

high backhand as there is no support for the sharp upward push on the disc just prior to release.<br />

A certain amount of control also depends on the position of the thumb, and how tight the grip is on the disc. In<br />

general, the tighter the grip, the more spin which is able to be imparted to the disc, and hence better control in<br />

the wind. The thumb can also be placed anywhere from along the rim of the disc to pointing towards the center<br />

of the disc.<br />

The best control, particularly with respect to air bounces, is to have the thumb pointing towards the center of the<br />

disc, and this also aids a tight grip. A tight grip also keeps the disc steady and makes high backhands easier to<br />

throw. On the down side, it seems a little harder to get as much distance with the thumb pointing toward the<br />

middle. This is because of the tendency to drag the thumb across the back edge of the disc on release.<br />

...The Hybrid Grip<br />

As its name suggests, this grip is a combination of the two grips shown above. It provides power with the index<br />

finger gripping the rim. It also gives support in an unusual way. The middle finger of the throwing hand is slightly<br />

extended so that the disc is supported by it.<br />

This grip makes it possible to throw all throws easily, including high backhands, without the need to change<br />

grips. The drawback is a slight loss of power in the throw, in the order of 5m over a 60m throw relative to a<br />

power grip. The comments with regard to thumb position apply equally to the hybrid grip as well as the power<br />

grip. [1]<br />

...The Backhand Throw<br />

Our natural tendency is to directly face the person we‘re throwing the disc to. Unfortunately, this often results in<br />

throws that veer wildly off target. So, position yourself accordingly:<br />

- If you‘re right handed, stand with your right shoulder toward your target; left handers should stand with their<br />

left shoulder facing the target.<br />

- Spread your feet about hip width apart, so that you have a more stable platform to throw from. Flex your<br />

knees slightly, so that your body is not rigid.<br />

- Bring your arm backwards, so that the disc is next to your rear leg and you feel your weight shift slightly<br />

back. Your forearm should not be parallel to the ground, but dropped a bit, so that the disc is at about a 45<br />

degree angle.<br />

Remember, the force in this throw comes not only through arm strength, but from your weight (and body mass)<br />

shifting forward as well.<br />

11

- Bring your arm forward with some force. Not a desperate heave, but a smooth, disciplined action. The disc<br />

should remain at an angle to the ground, although that angle may be decreased in a natural, swinging<br />

motion.<br />

- As you bring your arm forward, shift your weight forward and take a slight step ahead with your front foot.<br />

This will add force to the throw, so that your arm doesn‘t have to do all the work.<br />

Here‘s where it all comes together - with the final two components, release point and wrist snap.<br />

- Be aware of where the disc is while your arm is in motion. The point in the motion at which you release the<br />

disc will determine where the disc goes: left, right or straight ahead.<br />

- As you release the disc, snap your wrist forward, so that the disc „jumps“ off the side of your first finger. This<br />

will impart spin to the disc, and stabilize it in flight. The harder you snap the wrist, the more spin the disc<br />

gains and the better the throw will be.<br />

- Be careful to keep your wrist in line with your arm as you snap it. If you allow your thumb to lift upwards,<br />

you‘ll lose control of the disc and it won‘t go anywhere near ist target.<br />

- Continue your arm motion after the disc jumps off your finger. Known as „following through“, this will help<br />

direct the disc towards its target. [2]<br />

...The Backhand Throw - Advanced<br />

In Ultimate, you have to establish a pivot foot and since it is natural for righties to step forward with their left foot<br />

before throwing a baseball, they assume that they should pivot on their right foot. Okay, step back for a moment<br />

and think about how WRONG this is... Try to stand with your right foot stationary and reach as far to your right<br />

as possible, as if you‘re trying to hit a forehand in tennis. Now reach as far to your left as possible (with your<br />

right hand) as if you were trying to hit a backhand.<br />

Not much extension, eh? Alright, now try it with your left as the pivot foot, you can step all the way to one side<br />

with your right foot to hit the forehand, and then step all the way across your body to hit the backhand. MUCH<br />

more extension. In ultimate this is key, because there‘s a big hairy monster standing in front of you trying its<br />

darndest to keep you from throwing around it. The extra extension from pivoting on your left allows you to get<br />

around the monster. Remember, righties pivot on their left foot, lefties on their right.<br />

In the case of the backhand throw, first you step out so that your right foot is in front and to the left of your left<br />

foot (i.e. the line made by your feet is at a 45 degree angle to the direction you want the disc to go). Now put<br />

ALL your weight on your right foot... I‘m serious here, the only reason your left foot is still on the ground is<br />

because it‘s your pivot foot... it‘s good if only the big toe on your left foot is touching the ground. Practice<br />

throwing the backhand in this stance; Always maintain balance!!! [3]<br />

References<br />

[1] Hong Kong Ultimate Players Association, http://www.nunan.com/ultimate/docs/throws.html<br />

[2] Learn2.com, http://www.learn2.com/04/0469/0469.asp<br />

[3] GT Ultimate, http://cyberbuzz.gatech.edu/ultimate/mens/flick.html<br />

12

Learning to Throw Forehand<br />

There are two main factors to consider when throwing a disc; forward momentum and centrifugal force (spin). In<br />

other words, a well-thrown disc will have both sufficient wrist „snap“ AND force behind it. Wrist snap is often<br />

overlooked by novices, but is essential to throwing the disc successfully.<br />

Two additional important considerations are the angle to the ground at which the disc is released, and the point<br />

in the throw at which the disc is released. If this all sounds confusing, don‘t worry too much. With disc in hand,<br />

your physical instincts will kick in and grasp the mechanics fairly quickly.<br />

The Forehand (a.k.a. Flick)<br />

...The Basic Grip<br />

This grip is in principle very similar to the corresponding backhand grip. The middle finger of the throwing hand<br />

is inside the rim and the index finger is extended towards the center of the disc for support.<br />

The advantage of this method is control. The disadvantage is a corresponding loss of power, because the<br />

spreading of the fingers makes it impossible to cock the wrist back as far just before release.<br />

...The Power Grip<br />

There are a couple of different versions of this grip. The first has the index finger next to the middle finger and<br />

hard up against the rim.<br />

This grip increases power since the wrist can now be cocked back further and more snap imparted no the disc.<br />

As expected, there is a loss of control as there is no finger to support the disc. The disc has a tendency to<br />

wobble up and down, and this can reduce distance if the disc and the wrist are not at the same angle at release.<br />

The second is a slight improvement (not pictured), where the index and middle fingers are slightly curled, and<br />

the disc can balance on these two fingers prior to the throw. This grip is more like the hybrid grip below in the<br />

way it provides support. It also makes it easier to throw the high forehand.<br />

Like the backhand, the thumb should be used to grip the disc tightly. This will give better spin and more control<br />

in the wind, since the disc has less tendency to wobble during the wind-up and throw.<br />

13

...The Hybrid Grip<br />

This grip is analogous to the hybrid backhand grip, although it does seem to be more popular and widely used.<br />

Instead of the index finger and middle fingers being parallel, the index finger is slightly bent.<br />

This is exaggerated a little in the diagram. The pad of the index finger is pressed firmly on the rim, as is the pad<br />

of the middle finger. The bend in the index finger can then be used to support the disc, while the wrist can still<br />

be cocked well back for a power throw. The disc can be held out flat and ready to throw, which makes it a good<br />

grip for throwing the high forehand.<br />

...Other Grips<br />

The following grip is an interesting way of helping improve forehand throws in weaker players. Instead of the<br />

pads of the fingers being against the rim, the side of the middle finger is against the rim.<br />

This grip promotes a palm-up follow through, and helps stop people from turning their forehands over on<br />

release. The down side of this grip is that the snap puts lateral pressure on the finger joints, and persistent hard<br />

throws using this grip can damage the joints. It is therefore only recommended as a teaching aid, and not for<br />

use by experienced players. [1]<br />

...The Forehand Throw - Beginner<br />

Your stance here will be quite different from the backhanded throw.<br />

- If you‘re right handed, stand with your left shoulder forward, your torso turned slightly towards your target.<br />

Left handers stand with their right shoulder forward, torso turned slightly towards the target.<br />

- Keep your feet shoulder width apart and your arm behind your rear leg. Flex your knees again, so that your<br />

body‘s not rigid.<br />

- Bring your arm backwards, so that the disc is next to your rear leg and you feel your weight shift slightly<br />

back. Your forearm should not be parallel to the ground, but dropped a bit, so that the disc is at about a 45<br />

degree angle.<br />

In this throw, most of your force will actually come from the wrist snap and weight transfer, as your arm will<br />

move only a short distance.<br />

- Bring your arm forward with considerable force. Your elbow will be the pivot point, and your hand will<br />

actually stop with a jerk before it reaches your front leg.<br />

14

The importance of the release point and wrist snap are magnified with this throw.<br />

- As your arm only travels a short distance, the possible release points are much closer together. Even a<br />

slight variance will greatly affect the flight direction.<br />

- A good starting point is to release the disc just after your wrist crosses your rear leg. The disc angle must be<br />

fairly steep when released.<br />

Snap your wrist quite firmly as you release. This throw will not be successful unless the disc has good spin.<br />

After the disc leaves your hand, your first two fingers should remain firmly extended. Following through is not<br />

necessary or desirable in this instance.<br />

...Common Problems with the Forehand Throw<br />

The single most common fault is that the disc will turn over hitting the ground. This fault is caused by one or<br />

more of the following:<br />

- The angle of release is wrong<br />

- The disc wobbles too much<br />

- Turning the wrist over during the release<br />

- Not enough spin, especially with unstable discs or into the wind<br />

- Using a circular swing rather than „straight“ at the target<br />

- Not enough distance<br />

..Solutions<br />

The angle of release is wrong<br />

Usually the edge furthest away from the thrower is too high. If a beginner thinks he‘s releasing it level it<br />

generally has the outer tip up.<br />

- Lifting a leg and throwing under it. As well as forcing the release to be lower this also tends to keep far edge<br />

lower. It can also help get more flick into the throw. This not only works 75% of the time but also gets<br />

beginners psyched as hell; not only did they learn a new throw, but, in their mind, they learned a „trick“<br />

throw as well.<br />

- Stand closer and downwind so that you don‘t have to throw it harder.<br />

The disc wobbles too much<br />

- Keeping the disc flat during the swing. Avoid wind-ups where the disc is not in the horizontal plane.<br />

- Pull the disc rather than push it onto its flight path. Pulling the disc keeps the flight plate of the disc trailing<br />

behind the axis of the motion.<br />

Turning the wrist over during the release<br />

- Practice a palm facing up follow through. (Not a recommended technique for advanced throwers because it<br />

puts too much sideways force on the finger joints )<br />

The disc does not spin enough<br />

15

- Using a motion similar to flicking a towel<br />

- Start with the disc cocked (or „wound up“) as back as it can go. Check your grip.<br />

- Using more wrist rather than arm<br />

- Focus on the „catapult“ feeling that one gets in the middle finger<br />

- Pulling the disc forward with the fingers on the inside rim<br />

- Using a circular swing rather than „straight“ at the target<br />

- Lead the throw with the elbow<br />

- Follow through by pointing throwing hand at the target<br />

Not enough distance<br />

- Don‘t worry about it if you’re a beginner. Just more practice is required to get those finger muscles<br />

strengthened and the flick automatic. Most beginners try to throw the disc rather than flick it. Thus, if they<br />

concentrate on proper release angle (arm and disk) and imparting spin on the disc, a flick of the wrist, they<br />

tend to get the basics down quickly. Once the basics are there, the distance will<br />

Not enough accuracy<br />

- Check that the grip is not finger tips only and the swing is not circular, but in line to the target.<br />

- Can‘t remember all of the tips at once.<br />

- Return to basics. Remind yourself what it was like to learn, try throwing opposite handed for a while. [2]<br />

The Forehand Throw - Advanced<br />

Remember the pivot foot! First you step out so that your right foot is in front and to the right of your left foot (i.e.<br />

the line made by your feet is at a 45 degree angle to the direction you want the disc to go). Now put ALL your<br />

weight on your right foot... The only reason your left foot is still on the ground is because it‘s your pivot foot... it‘s<br />

good if only the big toe on your left foot is touching the ground.<br />

One mistake that people make is keeping their elbow pinned into their waist and flinging the disc forward. This is<br />

BAD. You want to start with your elbow near shoulder height and the disc into your body.<br />

Differences:<br />

- Notice at the top the elbow is pinched in, while at the bottom the elbow is out away from the body. At the<br />

top, she is leaning back, while at the bottom her weight is far forward and to the side.<br />

- At the bottom, her follow-through is far below the release point. This causes the back of the disc to drop<br />

down slightly, which allows you to throw with more touch. Note that you can actually see a tiny bit of the<br />

underside of the disc... This affects the flight by slowing it down as it travels and causes it to hang. This is<br />

good because you can throw the disc to a part of the field and have it almost stop completely. It will then just<br />

hang there for a second or two for someone to run on to.<br />

- One thing she‘s doing wrong in both pictures is that her arm never fully extends. When you snap down with<br />

your elbow, it whips your hand around, so that with very little effort you can generate a tremendous amount<br />

of speed (like snapping a towel). But you can only take advantage of this by fully extending your arm at the<br />

16

exact moment you flick the disc off your middle finger. Note also that follow-through should be palm-up and<br />

down and across your body.<br />

So when you‘re trying to practice this, these are the main points to remember:<br />

- Righties pivot on their left foot.<br />

- Don‘t step too far out, as you need to get your entire weight over your one leg.<br />

- Lean far forward and to the side.<br />

- Start with your elbow about shoulder height and disc into the body.<br />

- The snap starts with your elbow shooting down, whipping your hand around.<br />

- Your arm should be FULLY extended at the exact moment of release.<br />

- Follow through DOWN, with your palm facing up.<br />

- You should hold the disc so that your wrist is never bent... i.e., so that the back of your hand is in the same<br />

plane as the back of your forearm.[2]<br />

References<br />

[1] Frisbee Australia, http://www.afda.com/skills/grips.htm<br />

[2] Compiled by Maurice Cinquini with input from bo186@cleveland.Freenet.Edu (Retsu Takahashi),<br />

markh@sag4.ssl.berkeley.edu (Mark Hurwitz), lind@ils.nwu.edu (Jeff Lind), jims@bnr.ca (Jim Spallin),<br />

mwaa+@andrew.cmu.edu (Matthew S. Weiss), trills@matai.vuw.ac.nz (Judi Lapsley),<br />

pastore@humu.NOSC.Mil (Thomas J. Pastore), ferguson@cs.rochester.edu (George Ferguson),<br />

70540.1522@compuserve.com (Eric Simon), fau@po.CWRU.Edu (Francis A. Uy) donc@ISI.EDU,<br />

http://www.cs.uiowa.edu/~willemsn/ultimate/teaching_forehand<br />

17

After Your First Week<br />

Now that you‘ve got your first week of Ultimate under your belt and you‘ve been completely and utterly<br />

swamped with people trying to help, let‘s talk about what the hell they have been saying to you. Ultimate has<br />

more phrases than a millipede has legs.<br />

The Stall Count<br />

Every player has 10 seconds to throw the disc. If your check (i.e. the player defending you when you have the<br />

disc) is not counting, please remind them to count out loud to 10; often newer players forget. If someone is<br />

counting too fast you may call fast count; at this point they must go back 2 in the stall count. If they continue to<br />

count too fast and you call it again within the same stall count, the play stops and the count goes back to 0.<br />

Picks<br />

If any player on the field impedes the progress of a defensive player trying to check their offensive counterpart,<br />

the defensive player should call pick very loudly so play does not continue. If play continues and the disc is<br />

turned over, the turnover. The defensive player must be within 10 feet (3 meters) of their check to call a pick.<br />

Double Teams<br />

Only one defensive player may be within 10 feet of the thrower unless another offensive player is within a 10<br />

foot radius of the thrower.<br />

Fouls<br />

Fouls are the result of physical contact between opposing players. A catching foul may be called when there is<br />

contact between opposing players in the process of attempting a catch, interception, or knock down. A certain<br />

amount of incidental contact during or immediately after the catching attempt is often unavoidable and is not a<br />

foul. If a player contacts an opponent before the disc arrives and thereby interferes with that opponent‘s attempt<br />

to make a play on the disc, that player has committed a foul. If a player‘s attempt to make a play on the disc<br />

causes significant impact with a legitimately positioned stationary opponent, before or after the disc arrives, it is<br />

considered „harmful endangerment“ and is a foul.<br />

DANGEROUS, AGGRESSIVE BEHAVIOUR OR RECKLESS DISREGARD FOR THE SAFETY OF FELLOW<br />

PLAYERS IS ALWAYS A FOUL.<br />

If a catching foul occurs and is uncontested, the player fouled gains possession at the point of the infraction. If<br />

the call is disputed, the disc goes back to the thrower. If an uncontested foul occurs in the end zone, the player<br />

fouled gains possession at the closest point on the goal line to the infraction.<br />

Throwing fouls are when the thrower‘s passing motion is impeded by a moving marker prior to releasing the<br />

disc. If the marker is stationary the thrower may not step into them to complete a pass.<br />

18

Strips<br />

A defensive player may not knock the disc from the hands of an offensive player.<br />

Traveling<br />

The offensive player may not drag their pivot foot or run with the disc. A player who is running and catching<br />

must try to stop as quickly as possible (3 steps maximum) prior to throwing to a teammate.<br />

These are the most common rules. If someone is constantly breaking a rule, it may not be because they are<br />

unspirited; it may be because they don‘t know the rules.<br />

Transition<br />

I see it every time I watch newer players play Ultimate. They are on offense running down the field and a<br />

turnover occurs. It takes a second or two for them to realize that, „Hey, my team doesn‘t have the disc<br />

anymore,“ and by this time their check has run into the endzone and is wide open for a few seconds.<br />

Ultimate is a very high paced game and turnovers occur quite frequently. If you see the disc hit the ground, you<br />

should immediately find your check because he is going to try and roast you like you have never been roasted<br />

before. The instinct to become a defensive player is not natural. You are going one way, in control of everything,<br />

and then all of the sudden all the control is taken away from your team and given to your opponents. But there is<br />

something you can do about this. Get the disc back by playing some incredibly gnarly, layout, in your face D.<br />

Transition defense may also get some help form the marker. Your team should have picked a direction to force<br />

the disc in the event that you would wind up on defense. If the person who is, or will be marking the disc, sees<br />

someone wide open down field, he should put on what is called a „Straight Up Force“ for a few stall counts in<br />

order for that open person‘s check to catch up to him. By playing a straight up force, the marker is trying to<br />

prevent the thrower from hucking the disc a long distance. The marker should try to get back to the original force<br />

direction before too long or he will get broken, thus giving all the advantage back to the offense.<br />

More experienced players: You should be reading the play as it moves down field and if you see a potential<br />

turnover situation you should be preparing yourself to play defense before the disc even comes close to hitting<br />

the ground. This way you will be prepared to shut down the huck if someone on your team gets roasted by quick<br />

transition. This does not mean „don‘t have faith in your teammates“. You may be surprised how your team can<br />

come out of an adverse situation. As an experienced player you should have two or three strategies planned out<br />

for many different eventualities. If the pass is caught by a teammate you may find yourself wide open because<br />

your defender thought there would be a turnover. [1]<br />

Holding the Force<br />

This is probably one of the most misunderstood phrases in the game for new players. I will try to clarify it for<br />

you. The field has an imaginary line that originates at the disc and runs from end zone to end zone, parallel to<br />

the sideline. Got it!? All your stuff and your teammates‘ stuff and your water bottles and lawn chairs and<br />

umbrellas and your coolers full of beer and ... your ... this is the „Home“ side. The other side is the „Away“ side.<br />

At the beginning of each point your team should decide which way it is going to force your opponents to throw.<br />

For this example say you are forcing the thrower „Home“. This means that you are making a commitment to<br />

your teammates that you will not let the thrower throw to the „Away“ or „Closed“ side of the field. You should<br />

position yourself so that your body and arms are in a plane (not wrapping around the thrower as this is a foul)<br />

and you are at anywhere from a 45 to 90 degree angle to the thrower. (If you are at 90 degrees you would be<br />

facing directly „Home.“) From this position you should be light enough on your feet that if the thrower tries to<br />

step around your force (either forward or backward) you can move quickly to shut down the new angle the<br />

thrower establishes. Maintaining a force is critical as your teammates are depending on you to make the thrower<br />

throw in one particular direction. While you are forcing „Home“ your teammates are trying not to let their checks<br />

get open on the „Home“ of „Open“ side of the field. The figure below illustrates the „Home“ force.<br />

19

Reverse everything for an „Away“ force.<br />

Common phrases you’ll here on the ultimate field are:<br />

„Don‘t get broken“<br />

„Nothing Out“<br />

„No I/O“ or „No Inside/Out.“<br />

„No step around“<br />

All of these translate to HOLD THE FORCE. Have I made it painfully obvious yet that holding the force is<br />

probably the most important concept in defense?<br />

References<br />

[1] Mich‘s Guide to Ultimate (Vancouver Ultimate League), http://www.vul.bc.ca/<br />

[2] Ian „Scott“ Scotland Issue 34, November 1996, Page 11 British Ultimate Federation (BUF) Newsletter<br />

Ultimatum<br />

20

Drills<br />

Throwing in Pairs<br />

Each pair stands a comfortable distance apart and completes passes between each other to practice the basic<br />

techniques of throwing a forehand and backhand. This is used as a basic warm-up and practice at all levels of<br />

play.<br />

Variations:<br />

Get the throwers to throw high, floating passes to practice high catches.<br />

Increase the distance between the throwers to practice longer passes.<br />

Wheel Relay<br />

Forms a well-spaced circle facing inwards and with one person holding a disc. The first person passes the disc<br />

to their right and then runs around the outside of the circle in the opposite direction (clockwise). The disc is<br />

passed around the circle and meets the thrower as they arrive back in place. They pass it on to the next player<br />

(on the right) who then does the same thing. The relay continues until it is the original thrower‘s turn.<br />

Try to get players to throw backhands if right-handed and forehands if left-handed.<br />

Variations:<br />

Change the directions of passing and running so that both forehands and backhands are practiced. [2]<br />

Diamond Drill<br />

Form two stacks of at least three players each, facing each other behind cones about 15m apart. The first player<br />

from one line cuts to their right and is thrown the disc by the first player in the other stack. The thrower then<br />

makes the next cut to the other line, while the receiver continues through to join the end of the opposite line<br />

from which they came. Two extra cones may be used to provide a cutting and throwing target. After a while<br />

change the direction of cuts so that both backhands and forehands are practiced.<br />

Variations:<br />

Challenge the players to get 10 connections in a row.<br />

Have the receivers stop and return the disc to the line before joining the end of the line.<br />

Put a check on the thrower. [2]<br />

Kill Drill<br />

One person stands stationary for the entire drill. Second person starts out only about 4 to 5 meters away. Cuts<br />

from throwers left to right. Stationary person throws forehand (or inside out backhand) to cutting person quickly.<br />

Cutter sets, plants, and returns throw with a backhand and immediately cuts in the opposite direction. Thrower<br />

rewards cutter with a backhand this time. Cutter returns a forehand. Continue this drill for a timed period, then<br />

cutter becomes stationary thrower, and thrower becomes cutter.<br />

Circle Drill<br />

To run this drill properly, you need about 14 players. 11 of the players are on offense and stand in a circle. The<br />

remaining 3 players are on defense and are in the center of the circle. The circle should be at least 30 feet<br />

across. These numbers are all adjustable depending on the number of participants you have.<br />

The goal of the drill is for the offense to keep completing passes between each other while the defense tries to<br />

force turnovers. Each player on the offense can throw to any other player on offense except for the two players<br />

closest to them on both sides. The defense is arranged with one player marking the disc and the other two<br />

playing a loose cup to try to poach passes across the circle.<br />

21

Hammers and bloopers over the heads of the defenders are not allowed. Players on the offense cannot run into<br />

the circle to catch a short throw, but they can run out of the circle to catch a long throw. Each set of defenders<br />

stays in for five minutes. If an incompletion occurs, the guilty party must do a lap around the circle.<br />

The strategy for the offense is to keep moving the disc as fast as possible to tire out the defenders. The defense<br />

must work hard to force incompletions. [1]<br />

Three Player<br />

This is a great warmup drill before practice. It does not involve a great deal of running, but it is non-stop action.<br />

At any given point during the drill there is a thrower, receiver and a marker. After releasing the disc, the roles<br />

change: the receiver has the disc and becomes the thrower, the old thrower becomes the marker and must run<br />

down and mark the disc. The receiver must be stationary. The thrower and the receiver should be about 20 feet<br />

apart. The stall count is 5 seconds and the marker should start stalling at 6 (ie, „Stall 6, 7 8, 9, 10 STALL!“). If<br />

the throw is incomplete, players do not switch roles. Keep trying until you make a completion. [1]<br />

The more pressure the marker puts on the thrower the better the drill is. This is an excellent way to teach new<br />

players how to make a good throw when there is a defender. The thrower should try to break the mark and then,<br />

barring that, take what she or he can get. Hammers are declasse, but anything else is good.<br />

References<br />

[1] Ebb & Flow, http://www.menalto.com/EbbAndFlow/drills/BasicWeave.html<br />

[2] AFDA, http://www.afda.com/development/drills/index.html#pivotthrow<br />

The Cheer<br />

The first time you’re at an Ultimate game you might notice a lot of singing going on at the end of a game. That‘s<br />

because a quick Hip-Hip-Hooray to the other team just doesn‘t cut it in Ultimate. At the end of each game each<br />

team creates a customized cheer to salute their opponents.<br />

Usually it consists of taking a song that everybody knows and making up lyrics to commemorate the fun you had<br />

playing with your opponents. Recounting the game‘s highlights is nice, a little friendly slagging doesn‘t hurt, and<br />

naughty lyrics are welcomed.<br />

If you feel you can’t sing or aren‘t very good at coming up with words, don‘t worry. Enthusiasm counts more than<br />

talent when it comes to the cheer. It‘s just another extension of Spirit. No matter how bad or good your team did<br />

on that particular day, it‘s pretty hard to take yourself too seriously when a bunch of people are massacring a<br />

perfectly good pop song with off-key singing and x-rated lyrics.<br />

22

Buying Cleats<br />

Buying the right kind of cleats is an essential skill for any ultimate player. A poor choice could result in severe<br />

blistering, ankle problems, and even injury. Because there have been so many questions posted about this<br />

subject, I decided to take a survey using the rec.sport.disc newsgroup. In total, over 60 people responded,<br />

giving information about their favorite cleats, what they like about them, what they don't like, how they think<br />

cleats should be improved. The results of this survey are shown below.<br />

The biggest challenge I had was organizing the information into a format that people could use effectively. I<br />

decided on choosing the five most popular cleats and outlining their plus and minuses. Keep in mind that all<br />

these comments are based on consensus. There will undoubtedly be players who disagree with some of the<br />

results.<br />

Below are some useful comments made by players:<br />

"I usually get leather cleats big enough to shrink a little, then I soak them down and wear them while they dry.<br />

They get broke in pretty quick and the leather is soft, light, and comfortable. Right now for soft mud I have a pair<br />

with six removable cleats, and for everything else I have one with about thirty-something molded cleats."<br />

"It really comes down to what you feel comfortable with and what gives you the best traction on the type of turf<br />

you are playing on."<br />

"Seems like you need two sets. One for soft flat fields, screw ins, and one for rock hard baylands cement. I've<br />

thought of this a lot and have come to a couple conclusions: Football versus soccer screw-ins. Football design<br />

makes more sense for the type of cutting we do on the field. A good receiver or d-back football style will last<br />

longer than the soccer do. Made for more abuse by the cuts instead of ball control. The toe cleat on a football<br />

cleat is important in cutting. High or mid tops recommended. I see so many ultimate players with these light<br />

soccer shoes wearing those damn ankle braces it makes me sick. You'll get much more protection with<br />

integrated mid or high top support than adding a bulky uncomfortable brace. Getting the shoe that fits your foot<br />

is the main thing. And not a cheap pair either. It's your feet-- take care of them."<br />

"If you get too much traction, knee injuries are knocking at the door."<br />

" The difference in comfort and the process of being broken in is entirely different when there is a nice leather<br />

shoe versus a synthetic shoe. That is one of the reasons I like soccer cleats more than football cleats."<br />

"Keep the distance between your foot and the bottom of the shoe to a minimum - it decreases the chance of<br />

rolling your ankle. The problem this poses is a matter of comfort for the bottom of your feet."<br />

"While some folks will choose one pair for tourneys and one for practice, I prefer to alternate each time I play...<br />

with ultimate five days a week (two practices, two summer league nights, one pick-up) in the Summer, it helps<br />

me to maintain the upkeep of both feet and shoes to switch up cleats"<br />

"Soccer cleats in general work well as long as the ground is soft/gives a little. We've had several seasons in the<br />

past few years where the fields have gotten excessively hard after a drought period. With soccer cleats, this<br />

hard ground can cause a lot of problems from the impact with the ground. I had some trouble with my knees last<br />

year for this very reason. Shorter studs, and more of them, is good because it more evenly distributes the<br />

impact."<br />

GAIA Strike ($ 84.99 USD) (http://www.gaia-ultimate.com)<br />

Positive Comments:<br />

- Pretty durable<br />

- Very comfortable<br />

- No break in needed<br />

- Great ankle support<br />

- Lighter by far than other cleats.<br />

- Good for wet conditions<br />

- Toe is reinforced which is a big deal when you pivot a lot (my old cleats always wore out on the pivot foot<br />

toe)<br />

- I love the super hard base on the gaia, it gives you a very solid surface to push off when cutting on hard<br />

ground.<br />

23

Negative Comments:<br />

2nd pair of Gaias don't fit as well as the first pair I bought. Despite being the identical model and size.<br />

- Me and all my teammates have noticed that you need at least a heel cup if not an extra sole with these.<br />

If they can fix the fit a little, they'll be pretty much perfect.<br />

- They are showing wear after a year.<br />

- They take some time to stretch in the toebox. It took me about 2 months before I thought they were<br />

comfortable.<br />

- The only thing that would make them better is for the cleats to be moved closer to the edge of the sole.<br />

Adidas Copa Mundial ($ 99.99 USD) (http://www.adidas.com)<br />

Positive Comments:<br />

- Good for gripping the ground<br />

- Soft kangaroo leather breaks in immediately, lasts forever.<br />

- Lightweight and fast<br />

- I use it because it is a molded cleat that works well on the hard california surfaces where we have most of<br />

our tournaments.<br />

- Flexible<br />

- No blisters ever, light, lasts for years even with a beating<br />

Negative Comments:<br />

- Better insoles. Weren't cushioned enough in the heel.<br />

- Adidas makes narrow shoes and my feet aren't so narrow. I've been leaning towards the Nike's which are<br />

wider.<br />

A little more ankle support would be great<br />

- They expand a little bit too much when it gets wet up here in Oregon.<br />

- Most of the Addidas models have little or no insole, and don't work well with my orthodics.<br />

- Every Addidas I have owned has developed a gaping hole on the toe or on the side near the front.<br />

- With soccer cleats, hard ground can cause a lot of problems from the impact. I had some trouble with my<br />

knees last year for this very reason.<br />

Nike Sharks ($80-120 USD) (http://www.nike.com)<br />

Positive Comments:<br />

- Pretty lightweight and breathable for hightops and grip well<br />

- Provide a lot of ankle support, so much so that I stopped wearing an ankle brace pretty soon after an injury<br />

and have not reinsured it.<br />

- I've been leaning towards the Nike's which are wider.<br />

- I have had them for 3+ years and still wear them regularly.<br />

- solid, available, less ankle rotation than screw-ins.<br />

- They have a little more cushion than the most addidas cleats.<br />

- The assorted "teeth" make them wearable on a variety of surfaces. Good for summer at venues with<br />

variable (grass coverage/drainage) pitch qualities, especially where the ground is hard under the grass.<br />

Negative Comments:<br />

- Partially made of fake suede-like material that rips pretty easily when wet. So, I have gaping holes where<br />

my arch flairs out to couple with my big toe. However, I can still wear them and it doesn't seem to detract<br />

from the comfort or performance<br />

Kelme Turf Shoe ($80 USD) (http://www.kelme.com)<br />

Positive Comments:<br />

- The Kelme Turf shoes rock for hard fields<br />

- They have a wide toebox<br />

- If you have a wide foot get Kelme Turf shoes. They are great on dry ground and your feet will thank you.<br />

Negative Comments<br />

- Turf shoes clog in wet conditions<br />

Nike Speed TDs ($80 USD) (http://www.nike.com)<br />

Positive Comments:<br />

- The shoes are super light, great for traction, and the baseplate curves up on the sides to prevent your foot<br />

from sliding around when making hard cuts.<br />

- They're very very very light; they have an excellent cleat pattern, similar to Slams, but with longer, and<br />

round cleats that are better for really mushy conditions.<br />

24

Intermediate<br />

The Stack<br />

Ultimate is a game of flow. A good offense is characterized by quick passes, one after the other, that quickly<br />

move up the field. One of the most tell-tale signs of a beginner team is the problem of ‚clogging‘. With fourteen<br />

players on the field at any given time, twelve of which are running in order to try and get open for the pass,<br />

things very quickly get chaotic, and disorganized. People begin to find that it is difficult to get open because<br />

someone is always in their way. Because picks are a violation in ultimate, you also find that occasionally you<br />

must stop so that you don‘t inadvertently pick an opponent. The most common strategy for reducing clogging is<br />

called ‚stacking‘.<br />

The idea behind the stack is simply to make room on the field. Essentially, the players line up down the field<br />

from the disc. The first player lines up about 15-20 yards away, and the other players line up behind, with a<br />

separation of about 5-10 yards. Because ultimate is most commonly played using a ‚player-on-player‘ defense,<br />

this draws the opposing team into a similar configuration. The field directly ahead of the disc is now opened up<br />

for pass reception. Generally, players at the head of the stack (closest to the disc) are called ‚handlers‘, players<br />

in the middle are called ‚mids‘, and players towards the end of the stack are ‚longs‘.<br />

Theory<br />

Players can now make running plays to try and get open for the pass. This is usually done in a cascade of ‚cuts‘.<br />

The player at the beginning of the stack runs towards the thrower, and then cuts sharply to the right or the left<br />

(those with knee injuries will want to moderate the severity of the cut to reduce joint stress). This sharp cut<br />

usually gets the player a step or two in front of the defense. It is important to get eye contact with the thrower<br />

just before the cut. This running pattern gives the offense good chances for leading passes (thrown in front of,<br />

not at, the running player).<br />

If the thrower elects not to attempt a pass, the runner will circle back and re-enter the stack (preferably near<br />

where they began). By the time the runner begins to circle back, the second runner in the stack should already<br />

be making her cut. It takes some ‚field sense‘ in order to determine the optimum time for making a cut, but you<br />

want the thrower to have a new pass option immediately after an old one evaporates—this ensures best usage<br />

of the 10 second stall count.<br />

If the pass is received, someone further along in the stack should immediately begin to run. This way, when the<br />

receiver (now thrower) turns around, a pass option opens up right away.<br />

25

Player ‚1‘ has just made a successful pass to Player ‚2‘, and has begun to run up-field in order to re-enter the<br />

stack. Further up the stack, a mid has just started running (#1). By the time ‚2‘ looks up-field, Cut #1 is already<br />

happening—there should be an opportunity for a quick successive pass. If #1 does not look good, another<br />

player in the stack should already be making Cut #2. By the time #1 or #2 receives the pass, Player ‚1‘ may be<br />

ready to receive another pass, or else they can look downfield towards the stack which has now moved back a<br />

few yards.<br />

Finally, as mid-field is reached, players continue to make cuts, but ‚longs‘ can now begin to think about making<br />

a short cut inwards, and then attempting to make runs at the end-zone. This is done while the handlers and<br />

mids continue to attempt this steady cascading ‚weave‘ up the field.<br />

A player has just received the disc. They look down the field, and see that Cut #1 is already happening. It is a<br />

long, who immediately turns down field and breaks for the end-zone. If she is out-distancing her defender, it<br />

may be possible to throw a long bomb for a scoring attempt. If it doesn‘t look good, Cut #2 is already happening,<br />

and provides the opportunity for a short pass. Otherwise, the previous thrower may be getting into position<br />

across the field for a third option.<br />

This cyclical type of play, with the cascade of cutting runners makes a very fast flowing offense possible<br />

because the running patterns do not cross each other chaotically. Instead, the offense attempts to set a tempo<br />

of short quick passes, with the opportunity of surprise long passes to get the disc up the field. When this is<br />

executed well, it is beautiful to watch.<br />

In Practice<br />

There is no question that it takes a great deal of practice to make these kinds of plays smooth. And when you<br />

look at the diagrams that I have drawn, things look very complicated. When should you run, and how? In this<br />

section, I‘ll discuss briefly the tactics at an individual level that will make it possible for the stack to work for the<br />

team.<br />

Guidelines for the Cutter<br />

The key to the stack is order. By order, I mean a nice sequence of running. It requires a sense of timing which<br />

may take some time to develop. The idea is to always have someone cutting towards an open space so that the<br />

thrower has opportunities to move the disc forward. If you are the first cutter, begin running as soon as the disc<br />

is received. Make eye contact with the thrower, then quickly go one way or the other. If the thrower does not<br />

26

pass to you, get out of the way. By getting out of the way quickly, you draw your defender with you. This give<br />

the next cutter an open area to work with. If you are the second cutter, if you see that the disc is not going to be<br />

thrown to the first, then begin running immediately, make eye contact, and then a cut. Every run should be<br />

aimed at providing a new pass opportunity immediately after the last.<br />

As the disc moves down the field, the stack should be slowly backstepping to follow the movement.<br />

Guidelines for the Thrower<br />

Once you‘ve received your pass, turn around quickly and look upfield. If your stack is good, someone should<br />

already be cutting. This is your best chance to make a pass—before someone catches up to you and begins<br />

counting.<br />

If your team is running well, there should be an abundance of passing opportunities. The most important thing in<br />

passing is to ‚lead‘ the receiver by throwing the disc ahead of them, not at them. A throw directly at the receiver<br />

will cause them to try and immediately stop. If they cannot stop, the defender will be right there to intercept the<br />