Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

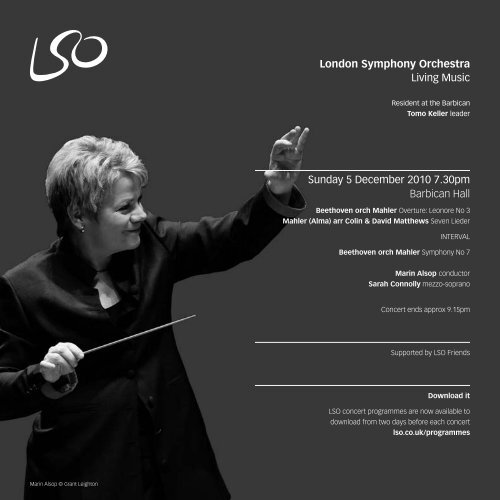

<strong>Marin</strong> <strong>Alsop</strong> © Grant Leighton<br />

<strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

Living Music<br />

Resident at the Barbican<br />

Tomo Keller leader<br />

Sunday 5 December 2010 7.30pm<br />

Barbican Hall<br />

Beethoven orch Mahler Overture: Leonore No 3<br />

Mahler (Alma) arr Colin & David Matthews Seven Lieder<br />

INTERVAL<br />

Beethoven orch Mahler <strong>Symphony</strong> No 7<br />

<strong>Marin</strong> <strong>Alsop</strong> conductor<br />

Sarah Connolly mezzo-soprano<br />

Concert ends approx 9.15pm<br />

Supported by LSO Friends<br />

Download it<br />

LSO concert programmes are now available to<br />

download from two days before each concert<br />

lso.co.uk/programmes

Welcome News<br />

Welcome to the LSO’s first concert of December where we welcome<br />

conductor <strong>Marin</strong> <strong>Alsop</strong> and mezzo-soprano Sarah Connolly.<br />

Tonight’s programme – Mahler’s orchestrations of Beethoven works,<br />

alongside songs by Mahler’s wife Alma – was conceived by <strong>Marin</strong><br />

<strong>Alsop</strong>, and is typically thought-provoking. Turn to page 10 to read her<br />

article on Mahler’s ‘retuschens’ (retouchings), which explains how, as<br />

listeners we might gain fresh insight into Beethoven’s works by seeing<br />

them through Mahler’s eyes.<br />

Sarah Connolly will be singing Alma Mahler’s Seven Lieder arranged<br />

by longstanding friends of the LSO, Colin and David Matthews.<br />

Although Alma composed many songs, her husband was unhappy<br />

with the idea of his wife working in such a way, and initially insisted<br />

that she stop. Only later did he recognise the quality of her songs and<br />

sought to have them published.<br />

Tonight’s concert is supported by LSO Friends. On behalf of everyone<br />

at the LSO, I would like to take this opportunity to thank them; their<br />

support and loyalty is invaluable. If you are interested in becoming an<br />

LSO Friend, contact Friends Co-ordinator Sophie Barnes on 020 7382<br />

2506, or visit the LSO Friends Desk on Level -1 during the interval.<br />

Kathryn McDowell<br />

LSO Managing Director<br />

Two weeks in Japan with Valery Gergiev<br />

The last two weeks have seen the <strong>Orchestra</strong> touch down in Japan,<br />

performing in Osaka, Tokyo, Omiya, Niigata and Chiba, to name but a<br />

few places. Our resident wordsmith and Principal Flute Gareth Davies<br />

has been blogging about all the goings-on; why not have a read via<br />

the address below? You can also view a great selection of tour photos<br />

on our Facebook page – check it out to see what the players have<br />

been getting up to, on and off duty (sampling local cuisine seems to<br />

be a recurring theme!)<br />

lsoontour.wordpress.com<br />

facebook.com/londonsymphonyorchestra<br />

LSO Live CDs – the perfect Christmas present<br />

If you’re stuck for gift ideas this Christmas, why not treat your nearest<br />

and dearest to the sound of the LSO in their own home? LSO Live is<br />

the best-selling orchestral own-label in the world, offering over 60 top<br />

quality CDs (including special edition box sets) from as little as £5.99.<br />

All CDs are shipped on the same or next working day, guaranteeing<br />

you much-needed wrapping time... Recent releases include Ravel’s<br />

Boléro and Rachmaninov’s <strong>Symphony</strong> No 2. For more details, to<br />

browse the complete catalogue and for special offers, visit:<br />

lso.co.uk/buyrecordings<br />

LSO Friends<br />

What does the LSO mean to you? Whatever it is, our Friends mean<br />

everything to us. They recognise our achievements and help us to<br />

go further, from full orchestral Barbican concerts to LSO Discovery<br />

groups for local residents and cross-genre groups with local teenagers,<br />

creating a truly 21st-century <strong>Orchestra</strong>. Membership starts from £50;<br />

in return, LSO Friends will receive 2011/12 priority booking as well<br />

as a regular behind-the-scenes magazine, chances to attend open<br />

rehearsals, and opportunities to meet LSO musicians at special events.<br />

lso.co.uk/lsofriends<br />

2 Welcome & News<br />

Kathryn McDowell © Camilla Panufnik

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) orch Gustav Mahler (1860–1911)<br />

Overture: Leonore No 3 (1814)<br />

Beethoven’s only opera Fidelio took ten years to reach its final state.<br />

In its first two versions, which were staged in 1805 and 1806, it was<br />

called Leonore; the overture known as Leonore No 2 was played<br />

at the 1805 production in Vienna, and an expanded and enhanced<br />

revision, Leonore No 3, in 1806 (confusingly, the overture Leonore No 1<br />

was written later, probably for a production in Prague that never took<br />

place). Beethoven was not satisfied with either of these versions and<br />

in 1814 made an extensive revision, which was performed with a new<br />

title, Fidelio, and with a new overture, which is the one played with the<br />

opera today.<br />

The second and third Leonore overtures share the same musical<br />

material and, like many operatic overtures, offer a resumé of the plot.<br />

Leonore No 3 begins in the darkness of the dungeon in which the<br />

hero Florestan has been unjustly imprisoned; the main allegro reflects<br />

his aspirations for political justice and his love for his wife, Leonore.<br />

An offstage trumpet, sounding twice, presages his release, and the<br />

overture ends in rejoicing. Beethoven, deciding that he had given too<br />

much away, first wrote Leonore No 1, which has a looser connection<br />

with the opera, and finally in Fidelio, a completely independent piece<br />

which, however, leads smoothly into the first scene.<br />

Because Leonore No 3 contains such magnificent music, some<br />

conductors, including Mahler, have played it between the two scenes<br />

of Act 2, but this reduces the effect of the final scene and is hardly<br />

ever done nowadays. Mahler also made revisions to the score of<br />

Leonore No 3, his common practice with Beethoven and with other<br />

composers he conducted, doubling the size of the woodwind from<br />

eight to sixteen to balance the strings, making many changes to the<br />

dynamics and some adjustments to the scoring.<br />

All programme notes © David Matthews<br />

David Matthews is a composer and writer. Among his many<br />

orchestral and chamber works are seven symphonies and twelve<br />

string quartets. His Seventh <strong>Symphony</strong> was premiered earlier<br />

this year by the BBC Philharmonic <strong>Orchestra</strong>. He has also written<br />

studies of Benjamin Britten and Michael Tippett, and numerous<br />

articles on contemporary music.<br />

<strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

‘He can unleash greater musical<br />

power with an elegant flick of<br />

the baton than most conductors<br />

muster with flailing arms’ The Times<br />

Sir Colin Davis’s Beethoven in 2011<br />

13 Mar <strong>Symphony</strong> No 7 & Piano Concerto No 3<br />

20 Mar <strong>Symphony</strong> No 6 (‘Pastoral’)<br />

with Mitsuko Uchida<br />

26 May Piano Concerto No 2<br />

2 Jun Piano Concerto No 1<br />

2 & 4 Oct Piano Concerto No 3<br />

4 & 6 Dec Piano Concerto No 4<br />

11 & 13 Dec Piano Concerto No 5<br />

On Sale Now<br />

020 7638 8891<br />

lso.co.uk<br />

Programme Notes<br />

3

Alma Mahler (1879–1964) orch Colin & David Matthews<br />

Seven Lieder (1901–11)<br />

1 Die stille Stadt (The silent city)<br />

2 Laue Sommernacht (Balmy summer night)<br />

3 Licht in der Nacht (Light in the night)<br />

4 Waldseligkeit (Bliss in the woods)<br />

5 In meines Vaters Garten (In my father’s garden)<br />

6 Bei dir ist es traut (I am at ease with you)<br />

7 Erntelied (Harvest song)<br />

Sarah Connolly mezzo-soprano<br />

Alma Schindler, daughter of a notable landscape painter and brought<br />

up in a bohemian milieu, studied the piano from an early age and at<br />

14 began lessons in composition with the blind composer and organist<br />

Josef Labor. When she was 20 she met Alexander von Zemlinsky, who<br />

had taught Schoenberg and was now a successful young composer.<br />

He took her as a composition pupil, and they fell in love: the affair was<br />

about to be consummated when Alma met Gustav Mahler and was<br />

caught up in his immediate wish to make her his wife. In a notorious<br />

letter soon after they were engaged he insisted that she would have<br />

to give up any ambition of being a composer: ‘From now on, would<br />

you be able to regard my music as if it were your own? … A husband<br />

and wife who are both composers: how do you envisage that? Such<br />

a strange relationship between rivals: do you have any idea how<br />

ridiculous it would appear … if we are to be happy together, you will<br />

have to be ‘as I need you’ – not my colleague, but my wife!’<br />

Alma reluctantly complied. But in 1910, when Mahler discovered that<br />

his wife had begun an affair with the architect Walter Gropius, he was<br />

suddenly full of remorse that he had forbidden her to compose. He<br />

insisted that she revise her songs, helped her with the revisions, and<br />

had five songs published by Universal Edition, his own publisher. It<br />

was too late for Alma, who had lost the will to be a composer: in the<br />

remaining 54 years of her life she wrote only a few more songs.<br />

All of Alma Mahler’s music, in fact, consists of songs with piano:<br />

17 survive, but she implies that there were many more; it is not<br />

clear what happened to the others, though we know that some of<br />

her manuscripts were lost in the war. All her songs are settings of<br />

4 Programme Notes<br />

contemporary poets, in a turn-of-the-century style that recalls her<br />

teacher Zemlinsky; all have strong melodic lines and affecting late-<br />

Romantic harmony. They reflect the spirited, ardent young woman that<br />

we encounter in her diaries. In 1995, my brother Colin and I arranged<br />

seven of her songs for orchestra, four from the 1910 volume and<br />

three from a second volume published in 1915. Colin orchestrated the<br />

two longest songs, In meines Vaters Garten and Erntelied, and I the<br />

remaining five. We tried to find an orchestral style that we believed<br />

Alma would have used had she been able to orchestrate them herself,<br />

one quite different from her husband’s, whose music when she first<br />

heard it she thought rather old-fashioned.<br />

INTERVAL: 20 minutes<br />

Enjoyed Sarah’s singing?<br />

Book now to hear her perform in Elgar’s thrilling oratorio The Kingdom<br />

under the baton of guest conductor and Elgar champion, Sir Mark Elder.<br />

Sun 30 Jan 7.30pm<br />

Elgar The Kingdom<br />

Sir Mark Elder conductor<br />

Cheryl Barker soprano<br />

Sarah Connolly mezzo-soprano<br />

Stuart Skelton tenor<br />

Iain Paterson bass<br />

<strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> Chorus<br />

‘I love the idea of taking<br />

[people] to places they’ve<br />

never been to before,<br />

musically’<br />

Sir Mark Elder<br />

Tickets start from just £8 – call the<br />

Box Office on 020 7638 8891<br />

or book online today at lso.co.uk

Alma Mahler<br />

Seven Lieder – Song Texts<br />

1 Die stille Stadt<br />

Liegt eine Stadt im Tale,<br />

Ein blasser Tag vergeht.<br />

Es wird nicht lange dauern mehr,<br />

Bis weder Mond noch Sterne<br />

Nur Nacht am Himmel steht.<br />

Von allen Bergen drücken<br />

Nebel auf die Stadt,<br />

Es dringt kein Dach, nicht Hof noch Haus,<br />

Kein Laut aus ihrem Rauch heraus,<br />

Kaum Türme noch und Brücken.<br />

Doch als dem Wandrer graute,<br />

Da ging ein Lichtlein auf im Grund<br />

Und durch den Rauch und Nebel<br />

Begann ein leiser Lobgesang<br />

Aus Kindermund.<br />

2 Laue Sommernacht<br />

Laue Sommernacht: am Himmel<br />

Stand kein Stern, im weiten Walde<br />

Suchten wir uns tief im Dunkel,<br />

Und wir fanden uns.<br />

Fanden uns im weiten Walde<br />

In der Nacht, der sternenlosen,<br />

Hielten staunend uns im Arme<br />

In der dunklen Nacht.<br />

War nicht unser ganzes Leben<br />

So ein Tappen, so ein Suchen?<br />

Da: In seine Finsternisse<br />

Liebe, fiel Dein Licht.<br />

3 Licht in der Nacht<br />

Ringsum dunkle Nacht, hüllt in Schwarz mich ein,<br />

zage flimmert gelb fern her ein Stern!<br />

Ist mir wie ein Trost, eine Stimme still,<br />

die dein Herz aufruft, das verzagen will.<br />

1 The silent city<br />

A town lies in the valley;<br />

A pale day fades.<br />

It will not be long<br />

Before neither moon nor stars<br />

But only night shall rule the heavens.<br />

From all the mountaintops<br />

Mists descend upon the town;<br />

No roof nor yard nor house<br />

Nor sound can pierce the smoke,<br />

Not even a tower or a bridge.<br />

But as the traveller felt fear<br />

A tiny light shone below,<br />

And through smoke and mist<br />

A soft song of praise began<br />

From the mouth of a child.<br />

2 Balmy summer night<br />

Balmy summer night, in Heaven<br />

there are no stars, in the wide forests<br />

we searched ourselves deep in darkness,<br />

And we found ourselves.<br />

Found ourselves in the wide forests<br />

in the night, saviours of the stars,<br />

Held ourselves in wonder in each other’s arms<br />

In the dark night.<br />

Was not our whole life<br />

Just a groping, just a seeking,<br />

There in its darkness<br />

Love, fell your light.<br />

3 Light in the night<br />

Dark night all around, enveloping me in black,<br />

Timidly a star flickers yellow from afar!<br />

It’s to me like a comfort, a quiet voice,<br />

Which calls on your heart that wants to give up.<br />

Song Texts<br />

5

Kleines gelbes Licht, bist mir wie der Stern<br />

überm Hause einst Jesu Christ, des Herrn<br />

und da löscht es aus. Und die Nacht wird schwer!<br />

Schlafe Herz. Schlafe Herz. Du hörst keine Stimme mehr.<br />

4 Waldseligkeit<br />

Der Wald beginnt zu rauschen,<br />

Den Bäumen naht die Nacht,<br />

Als ob sie selig lauschen,<br />

Berühren sie sich sacht.<br />

Und unter ihren Zweigen,<br />

Da bin ich ganz allein,<br />

Da bin ich ganz dein eigen :<br />

Ganz nur Dein!<br />

5 In meines Vaters Garten<br />

In meines Vaters Garten<br />

– blühe mein Herz, blüh auf –<br />

in meines Vaters Garten<br />

stand ein schattiger Apfelbaum<br />

– Süsser Traum –<br />

stand ein schattiger Apfelbaum.<br />

Drei blonde Königstöchter<br />

– blühe mein Herz, blüh auf –<br />

drei wundersame Mädchen<br />

schliefen unter dem Apfelbaum<br />

– Süsser Traum –<br />

schliefen unter dem Apfelbaum.<br />

Die allerjüngste Feine<br />

– blühe mein Herz, blüh auf –<br />

die allerjüngste Feine<br />

blinzelte und erwachte kaum<br />

– Süsser Traum –<br />

blinzelte und erwachte kaum.<br />

Die zweite fuhr sich übers Haar<br />

– blühe mein Herz, blüh auf –<br />

sah den roten Morgensaum<br />

– Süsser Traum –<br />

Sie sprach: Hört ihr die Trommel nicht<br />

6 Song Texts<br />

Little yellow light, you are like a star to me<br />

Above the house of Jesus Christ the Lord, once,<br />

And there it goes out! And the night turns heavy!<br />

Sleep, my heart! You hear no voice any more!<br />

4 Bliss in the woods<br />

The woods begin to rustle<br />

and night approaches the trees,<br />

as if it were listening happily<br />

for the right moment to caress them<br />

And under their branches<br />

I am entirely alone;<br />

I am entirely yours,<br />

entirely yours!<br />

5 In my father’s garden<br />

In my father’s garden<br />

– blossom, my heart, blossom forth! –<br />

In my father’s garden<br />

Stands a shady apple tree<br />

– Sweet dream, sweet dream! –<br />

Stands a shady apple tree.<br />

Three blonde King’s daughters<br />

– blossom, my heart, blossom forth –<br />

three beautiful maidens<br />

slept under the apple tree…<br />

– Sweet dream, sweet dream! –<br />

Slept under the apple tree.<br />

The youngest of the three<br />

– blossom, my heart, blossom forth! –<br />

the youngest of the three<br />

blinked and hardly woke.<br />

– Sweet dream, sweet dream! –<br />

Blinked and hardly woke.<br />

The second cleared her hair from her eyes<br />

– blossom, my heart, blossom forth! –<br />

and saw the red morning’s hem<br />

– Sweet dream, sweet dream! –<br />

She spoke: ‘did you not hear the drum?’

– blühe mein Herz, blüh auf –<br />

Süsser Traum<br />

hell durch den dämmernden Raum?<br />

Mein Liebster zieht zum Kampf hinaus<br />

– blühe mein Herz, blüh auf –<br />

mein Liebster zieht zum Kampf hinaus,<br />

küsst mir als Sieger des Kleides Saum<br />

– Süsser Traum –<br />

küsst mir als Sieger des Kleides Saum!<br />

Die dritte sprach und sprach so leis<br />

– blühe mein Herz, blüh auf –<br />

die dritte sprach und sprach so leis:<br />

Ich küsse dem Liebsten des Kleides Saum<br />

– Süsser Traum –<br />

ich küsse dem Liebsten des Kleides Saum.<br />

In meines Vaters Garten<br />

– blühe mein Herz, blüh auf –<br />

in meines Vaters Garten<br />

steht ein sonniger Apfelbaum<br />

– Süsser Traum –<br />

steht ein sonniger Apfelbaum!<br />

6 Bei dir ist es traut<br />

Bei dir ist es traut,<br />

zage Uhren schlagen wie aus alten Tagen,<br />

komm mir ein Liebes sagen,<br />

aber nur nicht laut!<br />

Ein Tor geht irgendwo<br />

draußen im Blütentreiben,<br />

der Abend horcht an den Scheiben,<br />

laß uns leise bleiben,<br />

keiner weiß uns so!<br />

– blossom, my heart, blossom forth! –<br />

Sweet dream, sweet dream<br />

clearly through the twilight air!<br />

My beloved joins in the strife<br />

– blossom, my heart, blossom forth –<br />

My beloved joins in the strife out there,<br />

‘Kiss for me as victor his garment’s hem.’<br />

– Sweet dream, sweet dream. –<br />

‘Kiss for me as victor his garment’s hem.’<br />

The third spoke and spoke so soft,<br />

– blossom, my heart, blossom forth! –<br />

The third spoke and spoke so soft:<br />

‘I kiss the beloved’s garment’s hem.’<br />

– Sweet dream, sweet dream! –<br />

‘I kiss the beloved’s garment’s hem.’<br />

In my father’s garden<br />

– blossom, my heart, blossom forth! –<br />

In my father’s garden<br />

stands a sunny apple tree<br />

– Sweet dream, sweet dream! –<br />

Stands a sunny apple tree.<br />

6 I am at ease with you<br />

I am at ease with you,<br />

faint clocks strike as from olden days,<br />

Come, tell your love to me,<br />

But not too loud!<br />

Somewhere a gate moves<br />

Outside in the drifting blossoms,<br />

Evening listens in at the window panes,<br />

Let us stay quiet,<br />

So no one knows of us!<br />

Song Texts<br />

7

8<br />

7 Erntelied<br />

Der ganze Himmel glüht<br />

In hellen Morgenrosen;<br />

Mit einem letzten, losen Traum noch im Gemüt,<br />

Trinken meine Augen diesen Schein.<br />

Wach und wacher, wie Genesungswein,<br />

Und nun kommt von jenen Rosenhügeln<br />

Glanz des Tags und Wehn von seinen Flügeln,<br />

Kommt er selbst. Und alter Liebe voll,<br />

Daß ich ganz an ihm genesen soll,<br />

Gram der Nacht und was sich sacht verlor,<br />

Ruft er mich an seine Brust empor.<br />

Und die Wälder und die Felder klingen,<br />

Und die Gärten heben an zu singen.<br />

Fern und dumpf rauscht das erwachte Meer.<br />

Segel seh’ ich in die Sonnenweiten,<br />

Weiße Segel, frischen Windes, gleiten,<br />

Stille, goldne Wolken obenher.<br />

Und im Blauen, sind es Wanderflüge?<br />

Schweig o Seele! Hast du kein Genüge?<br />

Sieh, ein Königreich hat dir der Tag verliehn.<br />

Auf! und preise ihn!<br />

Song Texts<br />

7 Harvest song<br />

The whole sky glows<br />

In bright morning roses;<br />

With one last loose dream still in my soul<br />

My eyes drink in this light,<br />

More and more awake, like the wine of health.<br />

And now comes the glow of the day<br />

From that hill of roses, and the stir of its wings,<br />

Comes day itself, and filled with old love,<br />

That through it I shall overcome<br />

Grief of night and what else got lost,<br />

Day calls me up to its bosom!<br />

And as the woods and the fields ring<br />

And the gardens begin to sing.<br />

Far and dull the sea roars, awoken.<br />

I see sails gliding into the sunny distance,<br />

White sails of the fresh wind,<br />

Quiet, golden clouds aloft, clouds above<br />

And in the blueness are these migrant birds?<br />

Be quiet, o soul, are you not satiated?<br />

Look, a kingdom the day granted you.<br />

Go! Let your deeds praise it!

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) orch Gustav Mahler (1860–1911)<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> No 7 (1811–1812)<br />

1 Poco sostenuto – Vivace<br />

2 Allegretto<br />

3 Presto – Assai meno presto (trio)<br />

4 Allegro con brio<br />

The Seventh <strong>Symphony</strong> was composed in 1811–12, towards the<br />

end of an extraordinarily creative period for Beethoven. It was<br />

immediately followed by the Eighth, but then there were several<br />

lean years before the culminating works of his last period. The<br />

Seventh was premiered, with Beethoven conducting, at a concert<br />

in December 1813 which also included the first performance<br />

of Wellington’s Victory, the so-called ‘Battle <strong>Symphony</strong>’, hugely<br />

acclaimed at the time but now forgotten.<br />

Wagner famously called Beethoven’s Seventh <strong>Symphony</strong> ‘the<br />

apotheosis of the dance’ (and apparently once substantiated his<br />

remark by dancing to the <strong>Symphony</strong> to Liszt’s piano accompaniment).<br />

The other often quoted saying about the Seventh, attributed to<br />

Weber by Beethoven’s biographer Anton Schindler, that Beethoven<br />

was now ‘quite ripe for the madhouse’, may be spurious, though it<br />

probably represented Weber’s views. In any case, the impression<br />

given by these two remarks of an early 19th-century Rite of Spring<br />

is not entirely misleading. It could be claimed that Beethoven and<br />

Stravinsky are the two composers whose music most powerfully<br />

expresses the sensation of physical energy. In each of the four<br />

movements of the Seventh <strong>Symphony</strong>, Beethoven seizes on a small<br />

rhythmic phrase and repeats it over and over again: this sounds<br />

rather like minimalism, but minimalist energy is always static –<br />

running on the spot; whereas Beethoven’s harmony constantly<br />

changes and the music is always moving forward: it is dynamic<br />

in the fullest sense.<br />

With this emphasis on constant dynamism, there is no real slow<br />

movement, though the first movement begins with the largest<br />

and most impressive of all Beethoven’s slow introductions, with a<br />

wonderfully prolonged transition to the Vivace. A slow movement<br />

would normally be in a different key from the first, but the Seventh’s<br />

Allegretto continues in A – minor in place of major – and is a kind<br />

of stately dance, very serious, but instantly popular with audiences<br />

(at the premiere it was even encored). The change of key comes<br />

with the scherzo, which is in F and light-footed, in contrast to the<br />

resplendently sonorous trio in D, which comes twice. In the finale<br />

the energy reaches new Dionysian heights.<br />

Mahler made extensive retouchings to the score of the Seventh,<br />

as he did with other Beethoven symphonies he conducted. He<br />

told his friend and biographer Natalie Bauer-Lechner: ‘Beethoven’s<br />

symphonies present a problem that is simply insoluble for the<br />

ordinary conductor … Unquestionably, they need re-interpretation<br />

and re-working. The very constitution and size of the orchestra<br />

necessitates it: in Beethoven’s time, the whole orchestra was not as<br />

large as the string section alone today. If, consequently, the other<br />

instruments are not brought into a balanced relationship with the<br />

strings, the effect is bound to be wrong’. His many changes are<br />

mostly concerned with dynamics: some pages contain more than<br />

50 modifications (Mahler is very fond of ppp and occasionally even<br />

pppp); but he also rewrites instrumental parts, especially the horns<br />

and trumpets, and at one point in the scherzo removes nine bars<br />

of woodwind and horns altogether. He also doubles the woodwind<br />

and horns, and has the timpani retune in several places in the finale<br />

(something Beethoven never did within a movement).<br />

Mahler did not know that, at the premiere of the Seventh, Beethoven<br />

had a string section more or less the same size as his own in Vienna,<br />

and probably also a doubled wind section. Some contemporary<br />

critics censured Mahler for changing Beethoven’s scores (though he<br />

was by no means the only conductor of his generation to make such<br />

revisions), but it seems that he was ‘authentic’ before his time. And<br />

Mahler had an understanding of orchestration second to none, so<br />

that anything that he did is at least interesting and at best, revelatory.<br />

Programme Notes<br />

9

10<br />

Where does creation end?<br />

<strong>Marin</strong> <strong>Alsop</strong> discusses<br />

Gustav Mahler’s desire<br />

to make his mark on his<br />

idol’s work<br />

Improving upon creation is a complicated business. So it goes with<br />

the question of Mahler’s retuschens (retouchings) of Beethoven’s<br />

symphonies. For all of us, the Beethoven symphonies are a<br />

breakthrough moment, an arrival point in the history of Western<br />

civilization; serving as both fundamental building blocks as well as<br />

a measuring stick for all that came before and all that would follow.<br />

They embody the essence of the human spirit conveyed through<br />

the abstract beauty of our shared universal language, musical<br />

poetry and sung architecture. The thought of ‘bettering’ these<br />

symphonies is part sacrilege, part egomaniacal suicide, at best.<br />

But that is exactly what Gustav Mahler felt compelled to do.<br />

By the turn of the twentieth century, the Beethoven symphonies had<br />

risen to archetypal stature. It is a testament to Mahler’s unwavering<br />

musical opinion and single minded determination that he could not<br />

resist the compulsion to tweak Beethoven’s work and to adapt it to, in<br />

his opinion, better suit the contemporary orchestra, concert halls and<br />

listening public. Mahler felt Beethoven’s hand on his shoulder and was<br />

convinced that Beethoven would have not only approved of his edits,<br />

but most likely would have made them himself had he experienced<br />

the new developments in performance techniques.<br />

Article<br />

Spending time with Mahler’s ‘retuschens’, a term never actually<br />

used by Mahler, has been a revelation for me, albeit an unexpected<br />

one. For the ‘recreators’, such as myself, interpreting the Beethoven<br />

symphonies is a daunting prospect in itself. Interpreting Beethoven’s<br />

works through the lens of yet another highly opinionated, strong<br />

willed artist adds a whole new dimension to the challenge. Seeing<br />

where Mahler reinforces the instrumentation, graduates, shades and<br />

tiers the dynamics, and discovering his approach to taking liberties<br />

with the tempi, all give me enormous insight into Mahler’s personal<br />

view of Beethoven’s works. My goal, as recreator, is to gather as<br />

many clues as possible in my quest to unearth the compelling story<br />

behind the piece. I search for that magic key that unlocks the door<br />

to the creator’s psyche, giving me insight into his motivation for<br />

that particular creation. Working on Mahler’s retouchings had me<br />

constantly questioning whose story I was uncovering: Beethoven’s,<br />

or Mahler’s version of Beethoven’s story? Does it matter?<br />

Growing up as an artist under the wing of Leonard Bernstein,<br />

it matters hugely. Black notes on the white page without humanity<br />

are empty, like words without inflection or point of view. Just as I<br />

was always moved by Bernstein’s unwavering sense of righteousness,<br />

<strong>Marin</strong> <strong>Alsop</strong> © Grant Leighton

I was deeply impressed by Mahler’s sheer nerve. He would have<br />

known that every member of the Vienna Philharmonic felt a proprietary<br />

ownership of Beethoven’s music; it would not be a stretch to say that<br />

the Beethoven symphonies were already classical music’s biblical books.<br />

Mahler also revered Beethoven, but Mahler was the consummate<br />

creator and recreator, a conductor who transformed symphonic<br />

and operatic performance, setting the bar for artistic excellence<br />

miles above where it been before. His personal experience with the<br />

20th-century orchestra sent him down a messianic path to improve<br />

upon Beethoven’s work. But where then does Beethoven end and<br />

Mahler begin? Where does one draw the line and say ‘this is too much’?<br />

It is not unusual for musicians to comment<br />

that Beethoven, because of his deafness,<br />

may have been imagining something that was<br />

beyond the grasp of conventional instruments.<br />

In light of the extensive period of instrument revolution, the question<br />

of authenticity versus personal interpretation is a vivid and real<br />

one that we recreators constantly grapple with. Mahler’s edits<br />

give that question new weight and daunting significance. Though<br />

many musicians, critics and orchestra patrons were sceptical and<br />

sometimes even hostile towards Mahler’s ‘redaktions’ (editings), as<br />

he preferred to call them, his intention was to convey the spirit of<br />

the work, albeit at the expense of being sometimes faithless to the<br />

composer’s indicated orchestrations or dynamic indications. One<br />

would think this could be the result of a very arrogant conductor, yet<br />

we know from reminisces of his contemporaries that Mahler was<br />

humble to the art. Pianist, conductor and composer Ossip Gabrilovitch<br />

wrote, ‘No man ever had a more loving or truly sympathetic heart<br />

than Mahler, but with those who placed their art beneath their ego,<br />

he had not patience’. And just as Mahler was known to revise his own<br />

works, these editings of other composer’s works were constantly<br />

revised according to a variety of circumstances; hall acoustics and the<br />

particular abilities of the orchestra he was conducting were factors he<br />

considered when making adjustments.<br />

It is not unusual for musicians to comment that Beethoven, because<br />

of his deafness, may have been imagining something that was beyond<br />

the grasp of conventional instruments, or perhaps in an aural sense<br />

had one foot in this world and the other in the next. Mahler’s editing<br />

was intended to help Beethoven realise his soundworld had he had<br />

the resources of the modern orchestra: to Mahler, his editings were<br />

born out of respect to the Master.<br />

The extent of Mahler’s edits vary greatly, depending on the piece.<br />

With Beethoven’s Leonore Overture No 3, an overture Mahler<br />

performed frequently in concert and also incorporated between<br />

scenes of the last act of Fidelio, there is a minimum of alteration;<br />

Mahler actually capitalised on an orchestration technique that<br />

Beethoven himself already used in the overture – the thinning out<br />

of players to aid balance or enhance clarity. Beethoven applies this<br />

technique in the final section of the overture that begins with a flurry<br />

of scale passages in the first violins. Beethoven instructs that two or<br />

three violins begin the passage, then as the passage advances, more<br />

players are added. Mahler uses this same device at the beginning of<br />

the Allegro that follows the introduction of the overture.<br />

And though it is not a matter of editing, Mahler had definite ideas<br />

about how particular passages were to be played. As related by<br />

Mahler’s Leader of the New York Philharmonic, Mahler wanted the<br />

trumpet calls to be played non espressivo, because as Mahler stated,<br />

‘In the barracks one makes no nuances’.<br />

In Beethoven’s Seventh <strong>Symphony</strong>, Mahler’s alterations and edits are<br />

far more extensive, including repeatedly thinning out the scoring for<br />

clarity, and doubling certain passages for better projection. The main<br />

thing Mahler wanted to convey was what he felt was the intention<br />

of the symphony – that the audience leaves the hall with a feeling of<br />

Dionysian intoxication.<br />

If we can agree that Mahler’s primary goal was to emphasise and<br />

reinforce Beethoven’s intentions, I think we can experience new<br />

insight into Beethoven through Mahler’s eyes.<br />

© <strong>Marin</strong> <strong>Alsop</strong><br />

Article<br />

11

<strong>Marin</strong> <strong>Alsop</strong><br />

Conductor<br />

‘Under the careful baton of<br />

<strong>Marin</strong> <strong>Alsop</strong>, the feel-good factor<br />

was stratospheric.’<br />

The Guardian, Jul 10<br />

<strong>Marin</strong> <strong>Alsop</strong> is recognised across the world<br />

for her innovative approach to programming,<br />

her deep commitment to education and to<br />

the development of audiences of all ages.<br />

Her conducting career was launched in<br />

1989, when she was a prizewinner at the<br />

Leopold Stokowski International Conducting<br />

Competition in New York; in the same year<br />

she was the first woman to be awarded the<br />

Koussevitzky Conducting Prize from the<br />

Tanglewood Music Cente, where she was a<br />

pupil of Leonard Bernstein, among others.<br />

<strong>Marin</strong> <strong>Alsop</strong>’s success as Music Director<br />

of the Baltimore <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> was<br />

recognised in 2009, when her tenure was<br />

extended to 2015. She retains strong links<br />

with all of her previous orchestras – the<br />

Bournemouth <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong>, where<br />

she was Principal Conductor from 2002 to<br />

2008 and now holds the post of Conductor<br />

Emeritus, and the Colorado <strong>Symphony</strong><br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong>, where she was Music Director<br />

from 1993 to 2005 and is now Music Director<br />

Laureate. Since 1992, <strong>Marin</strong> <strong>Alsop</strong> has been<br />

Music Director of California’s Cabrillo Festival<br />

of Contemporary Music, where she has built<br />

a devoted audience for new music.<br />

<strong>Marin</strong> <strong>Alsop</strong> is a regular guest conductor<br />

with the New York Philharmonic, Philadelphia<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong> and Los Angeles Philharmonic, the<br />

Royal Concertgebouw <strong>Orchestra</strong>, Tonhalle<br />

Zürich, Orchestre de Paris, Bavarian Radio<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> and La Scala Milan. She has a<br />

close relationship with both the <strong>London</strong><br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> and the <strong>London</strong> Philharmonic<br />

and appears with them regularly. She also<br />

returns frequently to orchestras such as the<br />

Netherlands Radio Philharmonic, Frankfurt<br />

RSO, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, Danish<br />

Radio <strong>Symphony</strong>, Oslo Philharmonic and<br />

the Czech Philharmonic. She collaborates<br />

closely with the Southbank Centre, and<br />

in the 2009/10 season was appointed<br />

Artistic Director of the year-long Bernstein<br />

Project which culminated in a large-scale<br />

performance of his Mass.<br />

Since taking up her position in Baltimore<br />

in September 2007, <strong>Marin</strong> <strong>Alsop</strong> has<br />

spearheaded educational initiatives which<br />

reach more than 60,000 school and preschool<br />

students. In 2008, she launched<br />

OrchKids, an after-school programme<br />

designed to provide music education,<br />

instruments and mentorship to the city’s<br />

neediest young people. Another of her major<br />

initiatives as Music Director in Baltimore is<br />

the BSO Academy, a community venture that<br />

<strong>Marin</strong> <strong>Alsop</strong> first led in June 2010, whereby<br />

local non-professional musicians work<br />

in depth over the period of a week with<br />

members of the Baltimore <strong>Symphony</strong>.<br />

<strong>Marin</strong> <strong>Alsop</strong>’s extensive discography, which<br />

already includes a notable set of Brahms<br />

symphonies with the <strong>London</strong> Philharmonic<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong>, is further distinguished by a new<br />

Dvorák series, which has been praised in<br />

Gramophone magazine (Editor’s Choice,<br />

December 2010), International Record Review<br />

and Neue Musik-Zeitung. For her recent<br />

recordings of John Adams’s Nixon in China<br />

and Leonard Bernstein’s Mass, The Financial<br />

Times gave Nixon in China five stars, calling<br />

it an ‘incandescent performance’, whilst<br />

Gramophone chose the Mass as Editor’s<br />

Choice in its 2010 Awards.<br />

In 2008 <strong>Marin</strong> <strong>Alsop</strong> became a Fellow of the<br />

American Academy of Arts & Sciences, and<br />

in the following year was chosen as Musical<br />

America’s Conductor of the Year 2009. She is<br />

the recipient of numerous awards in the US<br />

and Europe, including a European Women of<br />

Achievement Award for 2007, and is the only<br />

conductor to receive a MacArthur Fellowship.<br />

12 The Artists<br />

<strong>Marin</strong> <strong>Alsop</strong> © Grant Leighton

Sarah Connolly<br />

Mezzo-soprano<br />

‘All her customary musicality was<br />

radiantly in evidence: she is an<br />

artist incapable of singing a<br />

broken or ugly phrase, and her<br />

ornamentation was exquisite.<br />

She looked wonderful, too.’<br />

The Telegraph, Jun 10<br />

Born in County Durham, mezzo-soprano<br />

Sarah Connolly studied piano and singing at<br />

the Royal College of Music, of which she is<br />

now a Fellow. She was made CBE in the 2010<br />

New Year’s Honours List.<br />

In opera, recent appearances include<br />

Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas at the Royal Opera<br />

House, Covent Garden; at La Scala, Milan and<br />

at La Monnaie, Brussels; Komponist (Ariadne<br />

auf Naxos) and Annio (La clemenza di Tito) at<br />

the Metropolitan Opera, New York; the title<br />

role in Giulio Cesare and Brangäne (Tristan<br />

und Isolde) at the Glyndebourne Festival;<br />

Gluck’s Orfeo and the title role in The Rape<br />

of Lucretia at the Bayerische Staatsoper,<br />

Sarah Connolly © Gautier Deblonde<br />

Munich; Sesto (Giulio Cesare) at the Paris<br />

Opera and Nerone (L’Incoronazione di<br />

Poppea) at the Gran Teatro del Liceu<br />

in Barcelona, and at the Maggio Musicale<br />

in Florence.<br />

She has also sung the title role in Maria<br />

Stuarda and Romeo (I Capuleti e i Montecchi)<br />

for Opera North; Komponist for the<br />

Welsh National Opera and Octavian (Der<br />

Rosenkavalier) for Scottish Opera. A favourite<br />

at English National Opera, her roles there<br />

have included Octavian; Handel’s Agrippina,<br />

Xerxes, Ariodante and Ruggiero (Alcina);<br />

the title role in The Rape of Lucretia; Ottavia<br />

(L’incoronazione di Poppea); Dido (Dido and<br />

Aeneas/The Trojans); Romeo, Susie (The<br />

Silver Tassie) and Sesto (La clemenza di<br />

Tito) – for which she was nominated for an<br />

Olivier Award for Outstanding Achievement<br />

in Opera.<br />

She has appeared in recital in <strong>London</strong><br />

and New York and her many concert<br />

engagements include appearances at<br />

the Aldeburgh, Edinburgh, Salzburg and<br />

Tanglewood Festivals and at the BBC Proms<br />

where, in 2009, she was a memorable<br />

guest soloist at The Last Night. Other recent<br />

engagements have included The Dream<br />

of Gerontius with the Boston <strong>Symphony</strong><br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong> and Sir Colin Davis; Das Lied von<br />

der Erde with the Royal Concertgebouw<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong> and Daniel Harding; Des Knaben<br />

Wunderhorn with L’Orchestre des Champs-<br />

Elysées and Phillippe Herreweghe; Tristan<br />

und Isolde with the <strong>Orchestra</strong> of the Age of<br />

Enlightenment and Sir Simon Rattle; La mort<br />

de Cléopâtre with the Hallé and Sir Mark<br />

Elder and Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder with<br />

the LPO and Vladimir Jurowski.<br />

Committed to promoting new music, her<br />

world premiere performances include Mark-<br />

Anthony Turnage’s Twice through the heart<br />

with the Schoenberg Ensemble conducted<br />

by Oliver Knussen; Jonathan Harvey’s Songs<br />

of Li Po at the Aldeburgh Festival and, most<br />

recently, Sir John Tavener’s Tribute to Cavafy<br />

at <strong>Symphony</strong> Hall, Birmingham.<br />

A prolific recording artist, her many discs<br />

include Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas with the<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong> of the Age of Enlightenment,<br />

Elgar’s Sea Pictures with the Bournemouth<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> (nominated for a<br />

Grammy Award) and Mozart’s Mass in<br />

C Minor and Haydn’s Scena di Bernice with<br />

the Gabrieli Consort and Paul McCreesh. Her<br />

recording of Handel arias with The Sixteen<br />

and Harry Christophers was described as ‘the<br />

definition of captivating’ and two recital discs<br />

The Exquisite Hour and Songs of Love and<br />

Loss have both won universal critical acclaim.<br />

Future engagements include Sesto at the<br />

Festival d’Aix-en-Provence; Clairon (Capriccio)<br />

at the Metropolitan Opera, New York and<br />

returns to the Paris Opera, Gran Teatro del<br />

Liceu in Barcelona, Glyndebourne Festival,<br />

English National Opera, and to the Royal Opera<br />

House, Covent Garden.<br />

Sarah Connolly studies with Gerald Martin<br />

Moore.<br />

The Artists<br />

13

On stage<br />

First Violins<br />

Tomo Keller Leader<br />

Lennox Mackenzie<br />

Nicholas Wright<br />

Nigel Broadbent<br />

Laurent Quenelle<br />

Harriet Rayfield<br />

Colin Renwick<br />

Ian Rhodes<br />

Sylvain Vasseur<br />

Rhys Watkins<br />

Gabrielle Painter<br />

David Worswick<br />

Violaine Delmas<br />

Eleanor Fagg<br />

Helen Paterson<br />

Alina Petrenko<br />

Second Violins<br />

Evgeny Grach<br />

Thomas Norris<br />

Sarah Quinn<br />

David Ballesteros<br />

Richard Blayden<br />

Belinda McFarlane<br />

Iwona Muszynska<br />

Philip Nolte<br />

Paul Robson<br />

Louise Shackelton<br />

Dunja Lavrova<br />

Oriana Kriszten<br />

Samantha Wickramasinghe<br />

Victoria Hands<br />

14 The <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

Violas<br />

Edward Vanderspar<br />

Malcolm Johnston<br />

Regina Beukes<br />

Richard Holttum<br />

Robert Turner<br />

Jonathan Welch<br />

Arnaud Ghillebaert<br />

Nancy Johnson<br />

Fiona Opie<br />

Caroline O’Neill<br />

Elizabeth Butler<br />

Philip Hall<br />

Cellos<br />

Timothy Hugh<br />

Alastair Blayden<br />

Jennifer Brown<br />

Noel Bradshaw<br />

Daniel Gardner<br />

Keith Glossop<br />

Hilary Jones<br />

Minat Lyons<br />

Judith Herbert<br />

Susan Dorey<br />

Double Basses<br />

Rinat Ibragimov<br />

Colin Paris<br />

Patrick Laurence<br />

Matthew Gibson<br />

Thomas Goodman<br />

Jani Pensola<br />

Benjamin Griffiths<br />

Simo Vaisanen<br />

Flutes<br />

Adam Walker<br />

Siobhan Grealy<br />

Eilidh Gillespie<br />

Piccolo<br />

Sharon Williams<br />

Oboes<br />

Jerome Guichard<br />

John Lawley<br />

Nicola Holland<br />

Cor Anglais<br />

Christine Pendrill<br />

Clarinets<br />

Andrew Marriner<br />

Chi-Yu Mo<br />

Lorenzo Iosco<br />

James Burke<br />

Bassoons<br />

Bernardo Verde<br />

Dominic Morgan<br />

Christopher Gunia<br />

Susan Frankel<br />

Horns<br />

David Pyatt<br />

Angela Barnes<br />

Jonathan Lipton<br />

Jeffrey Bryant<br />

Trumpets<br />

Roderick Franks<br />

Gerald Ruddock<br />

Offstage Trumpet<br />

Nigel Gomm<br />

Trombones<br />

Dudley Bright<br />

James Maynard<br />

Bass Trombone<br />

Paul Milner<br />

Timpani<br />

Antoine Bedewi<br />

Percussion<br />

Neil Percy<br />

Harp<br />

Karen Vaughan<br />

LSO String<br />

Experience Scheme<br />

Established in 1992, the<br />

LSO String Experience<br />

Scheme enables young string<br />

players at the start of their<br />

professional careers to gain<br />

work experience by playing in<br />

rehearsals and concerts with<br />

the LSO. The scheme auditions<br />

students from the <strong>London</strong><br />

music conservatoires, and 20<br />

students per year are selected<br />

to participate. The musicians<br />

are treated as professional<br />

’extra’ players (additional to<br />

LSO members) and receive<br />

fees for their work in line with<br />

LSO section players. Students<br />

of wind, brass or percussion<br />

instruments who are in their<br />

final year or on a postgraduate<br />

course at one of the <strong>London</strong><br />

conservatoires can also<br />

benefit from training with LSO<br />

musicians in a similar scheme.<br />

Mark Lee (first violin), Ilona<br />

Bondar (viola) and Yuki Ito<br />

(cello) took part in rehearsals<br />

for tonight’s concert as part<br />

of the LSO String Experience<br />

Scheme. Mark Lee also performs<br />

on stage this evening.<br />

The LSO String Experience<br />

Scheme is generously<br />

supported by the Musicians<br />

Benevolent Fund and Charles<br />

and Pascale Clark.<br />

List correct at time of<br />

going to press<br />

See page xv for <strong>London</strong><br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> members<br />

Editor Edward Appleyard<br />

edward.appleyard@lso.co.uk<br />

Print<br />

Cantate 020 7622 3401<br />

Advertising<br />

Cabbell Ltd 020 8971 8450

What does the<br />

LSO mean to you?<br />

Whatever it is,<br />

our Friends mean<br />

everything to us…<br />

Support the <strong>Orchestra</strong>.<br />

Become an LSO Friend.<br />

The LSO’s mission ‘To make the finest music available<br />

to the greatest number of people’ is at the core<br />

of everything we do. LSO Friends play a vital role<br />

in making this possible, by providing philanthropic<br />

support for the <strong>Orchestra</strong>’s concert season and a<br />

wide variety of LSO Discovery projects.<br />

Joining is easy and takes just a few minutes<br />

online, on the phone, or in person. LSO Friends<br />

Membership ranges from £50 to £500+. In return<br />

you will receive priority booking, advance season<br />

information, regular updates, the chance to attend<br />

open rehearsals, and the opportunity to meet the<br />

musicians at concerts and special events.<br />

Join online at lso.co.uk/lsofriends<br />

Call us on 020 7382 2506 or visit Intermezzo,<br />

the meeting place for Friends on Level -1,<br />

before each Barbican concert and during<br />

the interval.<br />

…Join us!<br />

lso.co.uk/lsofriends<br />

Gordan Nikolitch and Nikolaj Znaider © Kevin Leighton

Inbox<br />

Your thoughts and comments about recent performances<br />

My friends and I have seen<br />

Tim Garland many times and<br />

in many different line-ups but<br />

last Wednesday’s concert<br />

[at LSO St Luke’s] was really<br />

special. The addition of the<br />

extra musicians to the Storms<br />

Nocturnes Trio made for a<br />

great overall sound and the<br />

spin-off duos and trios added<br />

a wonderful variety to the<br />

proceedings. [Pianist] Geoffrey<br />

Keezer said on the night that<br />

LSO St Luke’s is a great venue<br />

and I must agree – it’s our<br />

favourite music venue in<br />

<strong>London</strong> ... giving a more intimate<br />

atmosphere than the large<br />

concert halls. More please!<br />

17 Nov 10, LSO St Luke’s<br />

Tim Garland & Neil Percy /<br />

UBS Eclectica: Momentum 2010<br />

16 Inbox<br />

‘Wonderful variety’<br />

Roger Phillips<br />

‘Transporting’<br />

David<br />

For me the Shchedrin concerto<br />

was largely undistinguished –<br />

a collective of small inauspicious<br />

riffs, an underwhelming<br />

orchestration, and a duration<br />

double its content merited ...<br />

the Mahler by comparison<br />

was an exhilarating triumph,<br />

sensationally played, visceral<br />

and moving, the LSO tender and<br />

violent, loving and scabrous by<br />

turns. The audience whooped<br />

their appreciation – and so did I.<br />

A wonderful triumphant<br />

transporting performance –<br />

bravo!<br />

19 Nov 10, Valery Gergiev & Olli<br />

Mustonen / Rodion Shchedrin &<br />

Mahler<br />

‘Remarkable’<br />

Robin Self<br />

The performance of the Elgar<br />

was sublime and in my living<br />

memory only Menuhin has<br />

played this concerto better than<br />

Znaider. I heard Yehudi on several<br />

occasions in the 1960s and<br />

1970s with various conductors<br />

including Boult and in my<br />

opinion, of living conductors, only<br />

Sir Colin [Davis] is his equal.<br />

This was, in fact, more Sir Colin’s<br />

performance than Znaider’s;<br />

the sounds that he produced<br />

from your orchestra (as he did<br />

in the recent recording) were<br />

remarkable. If I hear a greater<br />

performance in the future, I shall<br />

consider myself truly blessed.<br />

Please thank all your musicians,<br />

and especially Sir Colin, for a very<br />

memorable evening.<br />

10 Nov 10, Sir Colin Davis &<br />

Nikolaj Znaider / Elgar &<br />

Mendelssohn<br />

Want to share your views?<br />

Email us at comment@lso.co.uk<br />

Let us know what you think.<br />

We’d love to hear more from you<br />

on all aspects of the LSO’s work.<br />

Please note that the LSO may edit your<br />

comments and not all emails will be published.<br />

From Facebook and Twitter...<br />

Last Saturday I had the unbelievable<br />

luck listening to the LSO at the<br />

Luxemburgish Philharmony.<br />

It was an experience that I will never<br />

forget in my life. I wish I could listen<br />

to you every day (not just on CD).<br />

You guys made my life richer that<br />

day. I THANK YOU SO MUCH.<br />

Thomas [13 Nov 10, on tour]<br />

I was in the concert in Paris. That<br />

was completely amazing. I have<br />

never seen a relation between a<br />

soloist as strong as I saw it yesterday<br />

during the Brahms. Thank you at the<br />

LSO for this concert!<br />

Lionel Speciale [14 Nov 10, on tour]<br />

@AliceSaraOtt Fantastic performance<br />

with @londonsymphony – well done<br />

for stepping into some big shoes and<br />

filling them brilliantly.<br />

Mintergreen [7 Nov 10]