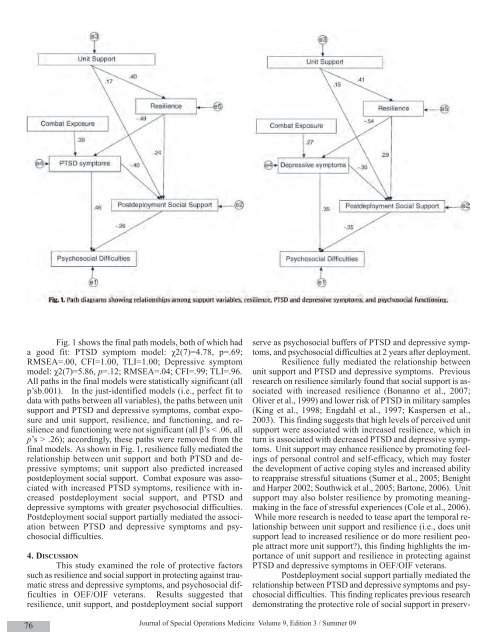

Fig. 1 shows the final path models, both of which hada good fit: PTSD symptom model: χ2(7)=4.78, p=.69;RMSEA=.00, CFI=1.00, TLI=1.00; Depressive symptommodel: χ2(7)=5.86, p=.12; RMSEA=.04; CFI=.99; TLI=.96.All paths in the final models were statistically significant (allp’sb.001). In the just-identified models (i.e., perfect fit todata with paths between all variables), the paths between unitsupport and PTSD and depressive symptoms, combat exposureand unit support, resilience, and functioning, and resilienceand functioning were not significant (all β’s < .06, allp’s > .26); accordingly, these paths were removed from thefinal models. As shown in Fig. 1, resilience fully mediated therelationship between unit support and both PTSD and depressivesymptoms; unit support also predicted increasedpostdeployment social support. Combat exposure was associatedwith increased PTSD symptoms, resilience with increasedpostdeployment social support, and PTSD anddepressive symptoms with greater psychosocial difficulties.Postdeployment social support partially mediated the associationbetween PTSD and depressive symptoms and psychosocialdifficulties.4. DISCUSSIONThis study examined the role of protective factorssuch as resilience and social support in protecting against traumaticstress and depressive symptoms, and psychosocial difficultiesin OEF/OIF veterans. Results suggested thatresilience, unit support, and postdeployment social supportserve as psychosocial buffers of PTSD and depressive symptoms,and psychosocial difficulties at 2 years after deployment.Resilience fully mediated the relationship betweenunit support and PTSD and depressive symptoms. Previousresearch on resilience similarly found that social support is associatedwith increased resilience (Bonanno et al., 2007;Oliver et al., 1999) and lower risk of PTSD in military samples(King et al., 1998; Engdahl et al., 1997; Kaspersen et al.,2003). This finding suggests that high levels of perceived unitsupport were associated with increased resilience, which inturn is associated with decreased PTSD and depressive symptoms.Unit support may enhance resilience by promoting feelingsof personal control and self-efficacy, which may fosterthe development of active coping styles and increased abilityto reappraise stressful situations (Sumer et al., 2005; Benightand Harper 2002; Southwick et al., 2005; Bartone, 2006). Unitsupport may also bolster resilience by promoting meaningmakingin the face of stressful experiences (Cole et al., 2006).While more research is needed to tease apart the temporal relationshipbetween unit support and resilience (i.e., does unitsupport lead to increased resilience or do more resilient peopleattract more unit support?), this finding highlights the importanceof unit support and resilience in protecting againstPTSD and depressive symptoms in OEF/OIF veterans.Postdeployment social support partially mediated therelationship between PTSD and depressive symptoms and psychosocialdifficulties. This finding replicates previous researchdemonstrating the protective role of social support in preserv-76Journal of <strong>Special</strong> <strong>Operations</strong> Medicine Volume 9, Edition 3 / <strong>Summer</strong> 09

ing functioning in both PTSD (Zatzick et al., 1997) and depression(Taylor, 2004; Oxman and Hull, 2001). It also suggeststhat providing early social support may reduce thedocumented postdeployment increase in PTSD symptoms andcomorbid conditions for OEF/OIF veterans (Milliken et al.,2007). Social support may enhance functioning by fosteringeffective coping strategies (Holahan et al., 1995), reducinginvolvement in high-risk behaviors or avoidance coping(Muris et al., 2001), promoting self-efficacy (Hays et al.,2001), and reducing loneliness (Bisschop et al., 2004). Resilienceand social support likely operate synergistically todecrease the likelihood of developing PTSD and depression.Indeed, a study of a nationally representative sample of 1632Vietnam veterans found that both hardiness, an aspect of resilience,and postwar social support were negatively associatedwith PTSD symptoms, and that social support accountedfor a substantial amount of the indirect effect of hardiness onPTSD (King et al., 1998).The finding that increased resilience was associatedwith increased postdeployment social support also corroboratesprevious research, which found that resilient individualstend to be skilled at constructing social networks and seekingout social support in times of need (Sharkansky et al., 2000).Resilience and social support may also protect against PTSDand depressive symptoms and enhance functioning by decreasinghypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis reactivityand stress-related physiological arousal (Heinrichs et al.,2003; Southwick et al., 2005). They may also promote activetask-oriented coping (Campbell-Sills et al., 2006), which enhancesadaptation to stress by decreasing avoidance symptoms,behavioral withdrawal, and emotional disengagement(Southwick et al., 2005; Tiet et al., 2006).Methodological limitations of this study must benoted. First, given the relatively low response rate to the survey,generalizability of the findings may be limited. Nevertheless,demographic, deployment, and clinical characteristicsof survey respondents in the current study were generallycomparable to those of a nationally representative sample ofOEF/OIF veterans (Tanielian and Jaycox, 2008), though thecurrent survey sample consisted of older, and predominantlywhite and Army Reserve/National Guard veterans, so resultsare likely best generalized to this population. Second, self reportscreening instruments were used to assess PTSD and depressionsymptoms. Whether these results are generalizableto larger, predominantly active duty, and/or more diverse samplesof OEF/OIF veterans when formal clinical interviewsand diagnostic instruments are utilized remains to be examined.Finally, due to the cross-sectional design of this study,we were unable to examine temporal relationships among thevariables assessed. More research is needed to examine theinterrelationships among these variables with respect to deployment.For example, it is not clear whether unit supportenhances resilience or if resilient individuals are better able toattract unit support. Future research should also employ abroader array of biological and psychosocial measures, includingmeasures of successful adjustment, in examining predictorsof psychological symptoms/disorders and functioning,and evaluate the utility of interventions designed to bolsterunit support, resilience, and postdeployment social support inimproving readjustment to civilian life in OEF/OIF veteransand other trauma-exposed populations.ROLE OF FUNDING SOURCENone of these funding sources had a role in study design; in thecollection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of thereport; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.CONFLICT OF INTERESTNone of the authors have any conflicts of interest.ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSWe thank the veterans who participated in this survey. We appreciatethe assistance of the Center for Public Policy and Social Researchat Central Connecticut State University and the ConnecticutDepartment of Veterans’ Affairs in conducting this research. Thiswork was supported by a grant from the State of Connecticut, Departmentof Mental Health and Addiction Services, the NationalCenter for PTSD, and a private gift.REFERENCESBartone, P.T., 1999. Hardiness protects against war-related stress in ArmyReserve forces. Consult Psychol J. 51, 72–82.Bartone, P.T., 2006. Resilience under military operational stress: Canleaders influence hardiness? Mil Psychol 18 (Suppl), S131–S148.Benight, C.C., Harper, M.L., 2002. Coping self-efficacy perceptions as amediator between acute stress response and long-term distress followingnatural disasters. J Trauma Stress 15, 177–186.Bisschop, M.I., Kriegsman, D.M.W., Beekman, A.T.F., Deeg, D.J.H., 2004.Chronic diseases and depression: The modifying role of psychosocialresources. Soc Sci Med 4, 721–733.Bonanno, G.A., Galea, S., Bucciarelli, A., Vlahov, D., 2007. What predictspsychological resilience after disaster? The role of demographics, resources,and life stress. J Consult Clin Psychol 75, 671–682.Brewin, C.R., Andrews, B., Valentine, J.D., 2000. Meta-analysis of riskfactors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults.J Consult Clin Psychol 68, 748–766.Campbell-Sills, L., Cohan, S.L., Stein, M.B., 2006. Relationship ofresilience to personality, coping, and psychiatric symptoms in youngadults. Behav Res Ther 44, 585–599.Cole, M., Bruch, H., Vogel, B., 2006. Emotions as mediators betweenperceived supervisor support and psychological hardiness on employeecynicism. J Organ Behav 27, 463–484.Connor, K.M., Davidson, J.R., 2003. Development of a new resiliencescale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). DepressAnxiety 18, 76–82.Engdahl, B., Dikel, T.N., Eberly, R., Blank Jr., A., 1997. Posttraumaticstress disorder in a community group of former prisoners of war: Anormative response to severe trauma. Am J Psychiatry. 154, 1576–1581.Hays, J.C., Steffens, D.C., Flint, E.P., Bosworth, H.B., George, L.K., 2001.Does social support buffer functional decline in elderly patients withunipolar depression? Am J Psychiatry. 158, 1850–1855.Holahan, C.J., Moos, R.H., Holahan, C.K., Brennan, P.L., 1995. Socialsupport, coping, and depressive symptoms in a late-middle-aged sampleof patients reporting cardiac illness. Health Psychol. 14, 152–163.Heinrichs, M., Baumgartner, T., Kirschbaum, C., Ehlert, U., 2003. Socialsupport and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol and subjective responsesto psychosocial stress. Biol Psychiatry. 54, 1389–1398.Previously Published 77

- Page 1 and 2:

Volume 9, Edition 3 / Summer 09 Jou

- Page 3 and 4:

An 18D deworms a camel during a “

- Page 5 and 6:

Field Evaluation and Management of

- Page 7 and 8:

The circumferential anchoring strip

- Page 9 and 10:

In doing so, all the skin is closed

- Page 11 and 12:

NATO SOF Transformation and theDeve

- Page 13 and 14:

current and future operations, thes

- Page 15 and 16:

sion of a physician, and limited pr

- Page 17 and 18:

REFERENCES1. James L. Jones, “A b

- Page 19 and 20:

This article is the first of two me

- Page 21 and 22:

Figure 4 : A Special Forces medic c

- Page 23 and 24:

exposure. Conversely, the customary

- Page 25 and 26:

7. Ted Westmoreland. (2006). Attrib

- Page 27 and 28:

first three days of injury, althoug

- Page 29 and 30: 9. Markgraf CG, Clifton GL, Moody M

- Page 31 and 32: the only sign of OCS may be elevate

- Page 33 and 34: E. The canthotomy allows for additi

- Page 35 and 36: 33. Rosdeutscher, J.D. and Stradelm

- Page 37 and 38: Tinnitus, a Military Epidemic:Is Hy

- Page 39 and 40: The development of chronic NIHL pro

- Page 41 and 42: supplied by diffusion. During expos

- Page 43 and 44: similar to those of other authors,

- Page 45 and 46: promising effect on tinnitus. Howev

- Page 47 and 48: ADDITIONAL REFERENCESHoffmann, G; B

- Page 49 and 50: et al. demonstrated that both right

- Page 51 and 52: TYPICAL CHEST RADIOGRAPH FINDINGS I

- Page 53 and 54: 11. Norsk P, Bonde-Petersen F, Warb

- Page 55 and 56: ABSTRACTS FROM CURRENT LITERATUREMa

- Page 57 and 58: tourniquet times are less than 6 ho

- Page 59 and 60: tal from July 1999 to June 2002. In

- Page 61 and 62: Operation Sadbhavana: Winning Heart

- Page 63 and 64: CENTRAL RETINAL VEIN OCCLUSION IN A

- Page 65 and 66: of the X chromosome. Notable is tha

- Page 67 and 68: AUTHORS*75th Ranger Regiment6420 Da

- Page 69 and 70: Casualties presenting in overt shoc

- Page 71 and 72: PSYCHOLOGICAL RESILIENCE AND POSTDE

- Page 73 and 74: spondents without PTSD (M = 4.6, SD

- Page 75 and 76: patients, whereas the mean score of

- Page 77 and 78: 29. Whealin JM, Ruzek JI, Southwick

- Page 79: average, time between return from d

- Page 83 and 84: Editorial Comment on “Psychologic

- Page 85 and 86: Blackburn’s HeadhuntersPhilip Har

- Page 87 and 88: The Battle of Mogadishu:Firsthand A

- Page 89 and 90: Task Force Ranger encountered enemy

- Page 91 and 92: Peter J. Benson, MDCOL, USACommand

- Page 93 and 94: Numerous military and civilian gove

- Page 95 and 96: Anthony M. Griffay, MDCAPT, USNComm

- Page 97 and 98: This is a great read that speaks di

- Page 99 and 100: and twenty-eight. Rabies immune glo

- Page 101 and 102: Rhett Wallace MD FAAFPLTC MC SFS DM

- Page 103 and 104: LTC Craig A. Myatt, Ph.D., HQ USSOC

- Page 105 and 106: LTC Bill Bosworth, DVM, USSOCOM Vet

- Page 107 and 108: Europe, Mideast, Africa and SWAU.S.

- Page 109 and 110: SOF and SOF Medicine Book ListWe ha

- Page 111 and 112: TITLE AUTHOR ISBNCohesion, the Key

- Page 113 and 114: TITLE AUTHOR ISBNI Acted from Princ

- Page 115 and 116: TITLE AUTHOR ISBNRats, Lice, & Hist

- Page 117 and 118: TITLE AUTHOR ISBNThe Healer’s Roa

- Page 119 and 120: TITLE AUTHOR ISBNGuerilla warfare N

- Page 121 and 122: TITLEAUTHORBlack Eagles(Fiction)Bla

- Page 123 and 124: TITLE(Good section on Merrill’s M

- Page 125 and 126: GENERAL REFERENCESALERTS & THREATSB

- Page 127 and 128: Aviation Medicine Resources: http:/

- Page 129 and 130: LABORATORYClinical Lab Science Reso

- Page 131 and 132:

A 11 year old boy whose tibia conti

- Page 133 and 134:

Meet Your JSOM StaffEXECUTIVE EDITO

- Page 135 and 136:

Special Forces Aidman's PledgeAs a