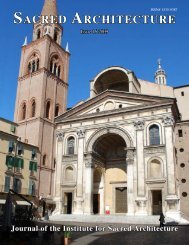

A R T I C L E Snot only failed to follow along with the liturgicalaction, but often busied themselveswith other things, often pious enough, butunrelated to the Eucharistic liturgy. 4 Withrelatively little interest in making the liturgicalaction visible to the congregation, altarswere sometimes set in deep chancelsand attached to elaborate reredoses thatoverwhelmed their tabernacles. Variousdevotional altars had their own tabernacles,which quite often doubled as statuebases. Overly large and colorful statuesonly compounded the problem. With theBlessed Sacrament reserved in multipletabernacles, the centrality of the Eucharisticliturgy as a unified act of communal worshipbecame less clear. Since clarity ofChurch teaching on the Eucharist and liturgywere key features of the LiturgicalMovement, architecture changed to serveits ends.Liturgical Principles and Church<strong>Architecture</strong><strong>The</strong> Liturgical Movement called <strong>for</strong> clarityin representing the centrality of the Eucharistand the pious participation of themembership of the Mystical Body of Christin the Eucharistic liturgy. At the most basiclevel, architects of the Liturgical Movementwanted to raise the quality of American liturgicallife. By making the liturgical regulationsof the <strong>Sacred</strong> Congregation of Ritesmore widely known, they hoped to bringabout consistent practice in order to increasethe reverence <strong>for</strong> the Mass and otherdevotions. <strong>The</strong>ir concerns were not merelylegalistic, however. Intimately connectedwith these goals was the desire to increasethe active and pious participation of the laity,and architectural changes followed almostimmediately to serve that end.Maurice Lavanoux lamented in a 1929article in Orate Fratres that American architectsand liturgists often failed to veil thetabernacle, ordered low quality churchgoods from catalogues, and designedreredoses that enveloped the tabernacleand thereby failed to make it suitablyprominent. 5 Art and historical continuitystill had their place, but now the two primarysymbols, the altar and crucifix,would dominate. Lavanoux asked that artiststreat the altar with proper dignity, notsimply view it as a “vehicle <strong>for</strong> architecturalvirtuosity.” He quoted M.S.MacMahon’s Liturgical Catechism in describingthe new arrangement of the altaraccording to liturgical principles. Insteadof the old Victorian pinnacled altar with itsdisproportionately small tabernacle,MacMahon wrote,the tendency of the modern liturgicalmovement is to concentrate attentionupon the actual altar, to remove the superstructureback from the altar or todispense with it altogether, so that thealtar may stand out from it, with itsdominating feature of the Cross, as theplace of Sacrifice and the table of theLord’s Supper, and that, with its tabernacle,it may stand out as the throneupon which Christ reigns as King andfrom which He dispenses the bounteouslargesse of Divine grace.<strong>The</strong> intention to simplify the altar originatedin a desire to emphasize the activeaspect of Mass and clarify the place of thePrototypical “liturgical altar” from Liturgical Arts magazine, 1931Photo: Liturgical Arts, 1931reserved Eucharist.Advocates of architectural and liturgicalclarity received a new mouthpiece with thepremiere of Liturgical Arts magazine in1931. Its editors wrote that they were “lessconcerned with the stimulation of sumptuousbuilding than…with the fostering ofgood taste, of honest craftsmanship [and]of liturgical correctness.” 6 <strong>The</strong> resistance tomere sumptuous building and the emphasison honesty were means by which the LiturgicalMovement sought to correct the architecturalmistakes of the nineteenth centurywhile maintaining a design philosophyappropriate <strong>for</strong> church architecture.This call <strong>for</strong> honesty and simplicity was tobe extraordinarily influential <strong>for</strong> two reasons:first, it was echoed strongly inSacrosanctum Concilium, and second, with achanged meaning it became the leitmotif ofModernist church architects.Specific architectural changes appearedquickly in new construction and renovations.Altars with tall backdrops were replacedby those with a solid, simple rectangularshape and prominent tabernacles.Edwin Ryan included instructions on thedesign of the appropriate altar in the inauguralissue of Liturgical Arts. 7 He asked <strong>for</strong>“liturgical correctness” and included animage of two prototypical altars fulfillingliturgical principles. <strong>The</strong> rectangular slabof the altar remained dominant, and thetabernacle stood freely. Its rounded shapefacilitated the use of the required tabernacleveil. <strong>The</strong> crucifix remained dominantand read prominently against a plain backdrop.<strong>The</strong> tester or baldachino emphasizedthe altar and marked its status. Ryan madeit clear that these suggestions were notmeant to limit the creativity of the architectand that “within the requirements of liturgicalcorrectness and good taste the fullestliberty is of course permissible.” A builtexample from the firm of Comes, Perry andMcMullen gave the high altar of St. Luke’sChurch in St. Paul, MN a figural backdrop.<strong>The</strong> sculpture group stood behind the altarand not on it, was dominated by the crucifix,and contrasted in color with the largetabernacle. Clarification of the place of thealtar and the tabernacle did not necessarilymean a bare sanctuary and absence of ornamentaltreatment.Another influential journal, ChurchProperty Administration, provided in<strong>for</strong>mationon the liturgical movement and its architecturaleffects. With a circulation ofnearly 15,000 in 1951 that included 128bishops, 11,007 churches and 802 architects,the magazine reached a popular audiencebut included numerous articles on architecturewhich evidenced the ideals of the LiturgicalMovement. Michael Chapmanpenned a piece called “Liturgical Movementin America” in 1943 that spoke of liturgicallaw, tabernacle veils and rubrics,but his underlying thrust grew out of thecontext of the liturgical movement. <strong>The</strong>14 Fall 2000 <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong>

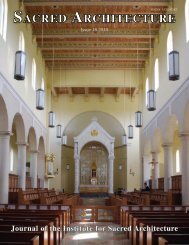

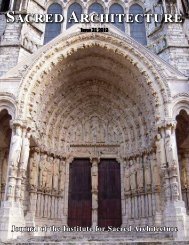

High altar, St. Luke’s Church, St. Paul, Minnesotachanges at the altar, he claimed, weremeant to “direct the attention of our peopleto the inner significance of the Action per<strong>for</strong>medat it.” <strong>The</strong> simplification of the altarand sanctuary was intended to help thealtar resume “its functional significance asthe place of Sacrifice; its very austerityserving to focus the mind and soul uponHim who is there enshrined, rather than onthe shrine itself.” 8 Chapman also critiquednineteenth century architects <strong>for</strong> reducingtabernacles to mere cupboards and reiteratedthat liturgical law <strong>for</strong>bade the nonethelesscommon practice of putting a statueor monstrance atop a tabernacle.<strong>The</strong> common abuse of using tabernaclesas stands <strong>for</strong> statues and altar crucifixes becameone of the immediate issues to resolve.This small but significant problemtied directly to the Liturgical Movement’saim to clarify the place of the Eucharist inthe life of the Church. Maurice Lavanouxlamented with “a sense of shame” that hehad once designed an extra-shallow tabernacle“so that the back could be filled withbrick as an adequate support” <strong>for</strong> a statue. 9Altar, tabernacle and statues were meant tobe brought into a harmonious wholethrough placement, treatment, and number.<strong>The</strong> various parts would amplify thetrue hierarchy of importance without diminishingthe rightful place of any individualcomponent of Christian worship orpiety. One author in Church Property Administrationtitled his article “Eliminate Distractionsin Church Interiors,” and suggestedthat all things which “distract attentivenessand reduce the powerof concentration” be removedor improved. 10 As H.A.Reinhold, one of the pioneers ofthe liturgical movement, put it,liturgical churches would “putfirst things first again, secondthings in the second place andperipheral things on the periphery.”11In the years leading up to theSecond Vatican Council, muchdiscussion continued concerningthe appropriate churchbuilding and the kind of designit required. <strong>The</strong> great majorityof architects and faithful held totheir traditions without fear ofappropriate updating. Whilecertain Modernist architectsbuilt high profile churchprojects, such as Le Corbusier’sNotre Dame du Haut (1950-54)and Marcel Breuer’s St. John’sAbbey in Minnesota (1961),most church architects avoidedthis type of modernism. Evenin 1948 when Reinhold suggestedthe possibility of semicircularnaves, priests facing thepeople, chairs instead of pews,and organs near the altar andnot in a loft, he would preserve his moretraditional sense of architectural propriety.Be<strong>for</strong>e the Council, a middle road of architecturalre<strong>for</strong>m emerged, one that sharedideas with the Liturgical Movement andMediator Dei. 12Photo: Cram, American Church Building of Today, 1929<strong>The</strong> Spirit of Mediator DeiIn his 1947 encyclical Mediator Dei, PiusXII praised the new focus on liturgy. Hetraced the renewed interest to severalBenedictine monasteries and thought itA R T I C L E Swould greatly benefit the faithful who<strong>for</strong>med a “compact body with Christ <strong>for</strong> itshead” (§5). However, one of the introductoryparagraphs explained that the encyclicalwould not only educate those resistantto appropriate change, but also addressoverly exuberant liturgists. Pius wrote:We observe with considerable anxietyand some misgiving, that elsewhere certainenthusiasts, over-eager in theirsearch <strong>for</strong> novelty, are straying beyondthe path of sound doctrine and prudence.Not seldom, in fact, theyinterlaid their plans and hopes <strong>for</strong> a revivalof the sacred liturgy with principleswhich compromise this holiest ofcauses in theory or practice, and sometimeseven taint it with errors touchingCatholic faith and ascetical doctrine(§8).Pius was concerned with abuses of liturgicalcreativity, a blurring of the lines betweenclerics and lay people regarding thenature of the priesthood, and the use of thevernacular without permission. In mattersmore closely related to art and architecture,he warned against the return of the primitivetable <strong>for</strong>m of the altar, against <strong>for</strong>biddingimages of saints, and against crucifixeswhich showed no evidence of Christ’spassion (§62). Mediator Dei offered strongrecommendations <strong>for</strong> sacred art as well, allowing“modern art” to “be given freescope” only if it were able to “preserve acorrect balance between styles tending neithertoward extreme realism nor to excessive‘symbolism’…”(§195). He deploredand condemned “those works of art, recentlyintroduced by some, which seem tobe a distortion and perversion of true artand which at times openly shock Christiantaste, modesty and devotion…” (§195). JesuitFather John La Farge, chaplain of theLiturgical Arts Society, lost no time in tak-Blessed Sacrament Church and Rectory, Sioux City, Iowa, 1958<strong>Sacred</strong><strong>Architecture</strong> Fall 2000 15Photo: Church Property Administration, March-April 1958