Download Issue PDF - The Institute for Sacred Architecture

Download Issue PDF - The Institute for Sacred Architecture

Download Issue PDF - The Institute for Sacred Architecture

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

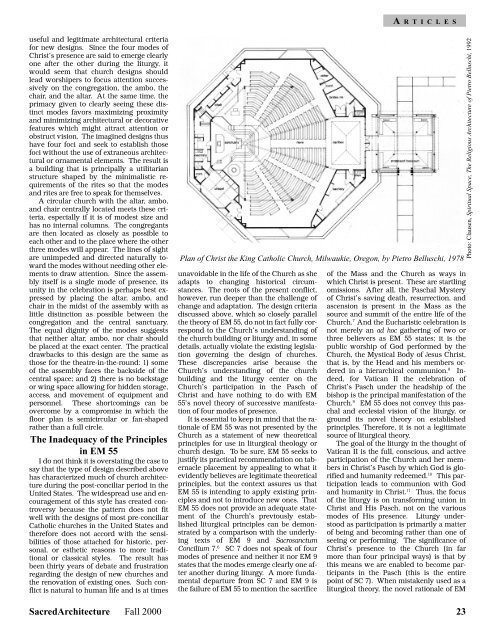

A R T I C L E Suseful and legitimate architectural criteria<strong>for</strong> new designs. Since the four modes ofChrist’s presence are said to emerge clearlyone after the other during the liturgy, itwould seem that church designs shouldlead worshipers to focus attention successivelyon the congregation, the ambo, thechair, and the altar. At the same time, theprimacy given to clearly seeing these distinctmodes favors maximizing proximityand minimizing architectural or decorativefeatures which might attract attention orobstruct vision. <strong>The</strong> imagined designs thushave four foci and seek to establish thosefoci without the use of extraneous architecturalor ornamental elements. <strong>The</strong> result isa building that is principally a utilitarianstructure shaped by the minimalistic requirementsof the rites so that the modesand rites are free to speak <strong>for</strong> themselves.A circular church with the altar, ambo,and chair centrally located meets these criteria,especially if it is of modest size andhas no internal columns. <strong>The</strong> congregantsare then located as closely as possible toeach other and to the place where the otherthree modes will appear. <strong>The</strong> lines of sightare unimpeded and directed naturally towardthe modes without needing other elementsto draw attention. Since the assemblyitself is a single mode of presence, itsunity in the celebration is perhaps best expressedby placing the altar, ambo, andchair in the midst of the assembly with aslittle distinction as possible between thecongregation and the central sanctuary.<strong>The</strong> equal dignity of the modes suggeststhat neither altar, ambo, nor chair shouldbe placed at the exact center. <strong>The</strong> practicaldrawbacks to this design are the same asthose <strong>for</strong> the theatre-in-the-round: 1) someof the assembly faces the backside of thecentral space; and 2) there is no backstageor wing space allowing <strong>for</strong> hidden storage,access, and movement of equipment andpersonnel. <strong>The</strong>se shortcomings can beovercome by a compromise in which thefloor plan is semicircular or fan-shapedrather than a full circle.<strong>The</strong> Inadequacy of the Principlesin EM 55I do not think it is overstating the case tosay that the type of design described abovehas characterized much of church architectureduring the post-conciliar period in theUnited States. <strong>The</strong> widespread use and encouragementof this style has created controversybecause the pattern does not fitwell with the designs of most pre-conciliarCatholic churches in the United States andthere<strong>for</strong>e does not accord with the sensibilitiesof those attached <strong>for</strong> historic, personal,or esthetic reasons to more traditionalor classical styles. <strong>The</strong> result hasbeen thirty years of debate and frustrationregarding the design of new churches andthe renovation of existing ones. Such conflictis natural to human life and is at timesPlan of Christ the King Catholic Church, Milwaukie, Oregon, by Pietro Belluschi, 1978unavoidable in the life of the Church as sheadapts to changing historical circumstances.<strong>The</strong> roots of the present conflict,however, run deeper than the challenge ofchange and adaptation. <strong>The</strong> design criteriadiscussed above, which so closely parallelthe theory of EM 55, do not in fact fully correspondto the Church’s understanding ofthe church building or liturgy and, in somedetails, actually violate the existing legislationgoverning the design of churches.<strong>The</strong>se discrepancies arise because theChurch’s understanding of the churchbuilding and the liturgy center on theChurch’s participation in the Pasch ofChrist and have nothing to do with EM55’s novel theory of successive manifestationof four modes of presence.It is essential to keep in mind that the rationaleof EM 55 was not presented by theChurch as a statement of new theoreticalprinciples <strong>for</strong> use in liturgical theology orchurch design. To be sure, EM 55 seeks tojustify its practical recommendation on tabernacleplacement by appealing to what itevidently believes are legitimate theoreticalprinciples, but the context assures us thatEM 55 is intending to apply existing principlesand not to introduce new ones. ThatEM 55 does not provide an adequate statementof the Church’s previously establishedliturgical principles can be demonstratedby a comparison with the underlyingtexts of EM 9 and SacrosanctumConcilium 7. 6 SC 7 does not speak of fourmodes of presence and neither it nor EM 9states that the modes emerge clearly one afteranother during liturgy. A more fundamentaldeparture from SC 7 and EM 9 isthe failure of EM 55 to mention the sacrificeof the Mass and the Church as ways inwhich Christ is present. <strong>The</strong>se are startlingomissions. After all, the Paschal Mysteryof Christ’s saving death, resurrection, andascension is present in the Mass as thesource and summit of the entire life of theChurch. 7 And the Eucharistic celebration isnot merely an ad hoc gathering of two orthree believers as EM 55 states; it is thepublic worship of God per<strong>for</strong>med by theChurch, the Mystical Body of Jesus Christ,that is, by the Head and his members orderedin a hierarchical communion. 8 Indeed,<strong>for</strong> Vatican II the celebration ofChrist’s Pasch under the headship of thebishop is the principal manifestation of theChurch. 9 EM 55 does not convey this paschaland ecclesial vision of the liturgy, orground its novel theory on establishedprinciples. <strong>The</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e, it is not a legitimatesource of liturgical theory.<strong>The</strong> goal of the liturgy in the thought ofVatican II is the full, conscious, and activeparticipation of the Church and her membersin Christ’s Pasch by which God is glorifiedand humanity redeemed. 10 This participationleads to communion with Godand humanity in Christ. 11 Thus, the focusof the liturgy is on trans<strong>for</strong>ming union inChrist and His Pasch, not on the variousmodes of His presence. Liturgy understoodas participation is primarily a matterof being and becoming rather than one ofseeing or per<strong>for</strong>ming. <strong>The</strong> significance ofChrist’s presence to the Church (in farmore than four principal ways) is that bythis means we are enabled to become participantsin the Pasch (this is the entirepoint of SC 7). When mistakenly used as aliturgical theory, the novel rationale of EMPhoto: Clausen, Spiritual Space, <strong>The</strong> Religious <strong>Architecture</strong> of Pietro Belluschi, 1992<strong>Sacred</strong><strong>Architecture</strong> Fall 2000 23