Download Issue PDF - The Institute for Sacred Architecture

Download Issue PDF - The Institute for Sacred Architecture

Download Issue PDF - The Institute for Sacred Architecture

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

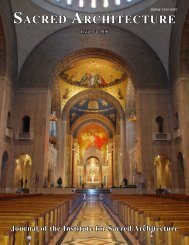

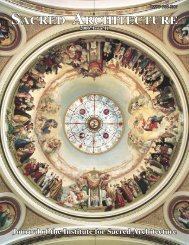

A R T I C L E SOhio. 16 Designed by Robert T. Miller ofCleveland, the building used a palette recallinghis early days as a designer of industrialbuildings but nonetheless maintaineda sense of Catholic purpose. <strong>The</strong>very large church seated 1,000 people, usingmaterials of steel, concrete block, andbrick. Despite the incorporation of industrialbuilding methods, the architect wascontent to let the “modern” materials be ameans rather than an end. <strong>The</strong> tall campanileproved visible <strong>for</strong> miles and the westfront of the building offered a grand entry.A well-proportioned Carrara marble statueof St. <strong>The</strong>rese in a field of blue mosaic withgold crosses and roses was surrounded byan ornamental screen inset with <strong>The</strong>resiansymbolism. A dramatic three-story facetedglass window with abstracted figural imagerygave the baptistery a grandeur it deserved.<strong>The</strong> sanctuary received dramaticnatural lighting over the high altar and itsprominent tabernacle. Images of Josephand the Virgin <strong>for</strong>m part of the scene, butwithout altars of their own. <strong>The</strong> symbolismin the aluminum baldachino joinedwith the precious materials of the altar toestablish its proper status. <strong>The</strong> altar carriedthe simple but essential message“Sanctus, Sanctus, Sanctus.” Modern materialscame together with a decorous arrangementof parts to <strong>for</strong>m a dignified contemporarychurch.<strong>The</strong>se churches were built in the spiritof Mediator Dei. <strong>The</strong>y eschewed the claimsof some <strong>for</strong> unusual shapes, banishment o<strong>for</strong>nament, and the use of exposed industrialmaterials. Despite the prevailing notionthat the post-war United States sawnothing but modernist architecture, in 1954three “traditional” churches were beingbuilt <strong>for</strong> every one “modern” church. 17Ironically, Modernist architect-heroes disproportionatelyfound their way into thesecular press, impressed other architectsand persuaded building committees. Nomatter how clearly the traditional architectsadopted features of the LiturgicalMovement, they could not compete withthe excitement of the stylistic avant-garde.<strong>The</strong> Modernist critique of traditional architecturereached all levels, from educationalinstitutions to popular culture to chanceryoffices.While leading architectural journalspraised the latest concrete designs, WilliamBusch, a liturgical pioneer and collaboratorwith Virgil Michel in the Liturgical Movement,asked readers to understand the truenature of a church building. In 1955 hepenned an article entitled “Secularism inChurch <strong>Architecture</strong>,” discussing the term“contemporary” and its associations withmodern secular buildings. Secularism inchurch architecture, he feared, would leadto buildings which would “lack the architecturalexpression which is proper to achurch as a House of God and a place of divineworship.” 18 Furthermore, he deniedInterior of St. Mary and St. Louis Priory Chapel, St. Louis, Missouri, by Hellmuth,Obata and Kassabaum. Featured in Liturgical Arts, November, 1962claims of some architectural modernists bywriting:A church edifice is not simply a place<strong>for</strong> the convenient exercise of prayerand instruction and <strong>for</strong> the enactment ofthe liturgy. <strong>The</strong> church edifice itself is apart of the liturgy, a sacred thing, madeholy by a divine presence through solemnconsecration: it is a sacramental object,an outward sign of invisible spiritualreality. 19<strong>The</strong> concept of the church building as a“skin” <strong>for</strong> liturgical action, as would bepresented later in documents like Environmentand Art in Catholic Worship (BCL,1978), was absolutely proscribed. In fact,Busch criticized architect Pietro Belluschi,who would become one of the major <strong>for</strong>cesin American church architecture, <strong>for</strong> seeinga church as “a meeting house <strong>for</strong> people.”He asked instead:Where is the thought of church architectureas addressed to God? And where isthe thought of God’s address to man inhallowing grace? Are we to imaginemodern society as in an attitude of moreor less agnostic and emotional subjectivism,and unconcerned about objectivetruth and the data of divine revelation? 20H.A. Reinhold, a prominent voice of theLiturgical Movement, also urged moderation.He asked that architects neither “canonizenor condemn any of the historicstyles,” rather, “appreciate all of thesestyles of architecture, each <strong>for</strong> its ownvalue.” 21 Although he spoke of “full participationof the congregation” he cautionedagainst centralized altars.Other writers and architects had differentideas, and many church architects whoignored Mediator Dei often received considerablenotoriety. Articles in Liturgical Artsbecame more and more clearly alignedwith a “progressive” notion of liturgical re<strong>for</strong>mat the same time that architecturalmodernism under architects like LeCorbusier and Pietro Belluschi were takinghold. Even be<strong>for</strong>e the arrival of the SecondVatican Council, Liturgical Arts was discussingabstract art <strong>for</strong> churches, presentingimages of blank sanctuaries, and encouragingMass facing the people. 22 Modernistarchitects and liturgists who privilegedwhat Pius XII called “exterior” participationin reaction to the individualismof the previous decades held the majorityopinions and established the normativeprinciples of new church architecture. 23<strong>The</strong> language of the Liturgical Movementfound its way into the documents ofVatican II and remains relatively unchangeddespite the variety of architecturalresponses that claim to grow from it.Phrases such as “noble simplicity” and “activeparticipation” were <strong>for</strong>mative conceptsin pre-Conciliar design which nonethelessallowed <strong>for</strong> a traditional architecture, onesuitably elaborate yet clear in its aims. Incontrast to the conceptions of post-Conciliararchitecture promoted by architecturalinnovators, the 1940s and 1950s providecontextual clues <strong>for</strong> the architecture ofthe Liturgical Movement. It is reasonableto ask whether the writers of SacrosanctumConcilium had the larger history of the liturgicalmovement in mind when they called<strong>for</strong> “noble beauty rather than mere extravagance”(SC, §124).Similarly, in understanding Vatican II’sstatement giving “art of our owndays…free scope in the Church” (SC, §123),it can be remembered that Pius XI (reigned1922-39) had chastised certain modern artists<strong>for</strong> deviating from appropriate art evenPhoto: Liturgical Arts, November, 1962<strong>Sacred</strong><strong>Architecture</strong> Fall 2000 17