water fountains in Georgia. But in ourGLSP office area, 18 counties, therewere still segregated movie theaters.When our office came upon MclntoshCounty (the subject of Praying forSheetrock), it was so isolated, so beautiful,it looked like Hilton Head, NorthCarolina, must have looked 100 yearsago."But the look of untouched, undevelopedcommunity had an ugly underside:"An old and isolated Black communitylived in a sort of pale outside acentury of American progress and success.<strong>The</strong> Black people survived by raisingvegetables and keeping chickens, byworking menial jobs in Darien (thecounty seat) and by fighting the networkof tidewater rivers and backwaterswamps. <strong>The</strong>y lived without plumbingor telephones, some without electricityor heat, well into the 1970s. <strong>The</strong>y sawtheir children bused to an all-Blackschool with used supplies and outdatedtextbooks. Few voted."Georgia Legal Services had been calledin to Mclntosh by three local Black men,Thurnell Alston, a disabled boilermaker;Rev. Nathaniel Grovner, and SammyPinkney, a disabled, former New YorkCity detective. Sick of business asusual, the three initiated a lawsuit toend the institutional racism at the coreof area government.Convincing longtime community residentsto sign on as plaintiffs in thelawsuit was no easy task, but GeorgiaLegal Services staffers gave it their all.<strong>On</strong>e particular meeting at the CalvaryBaptist Fundamental Independent MissionaryChurch is still vivid for Greene."At one point the minister invited me tostand up front to help lead a hymn. Ithanked him but declined, explainingthat on top of being unable to sing, I wasJewish. Welcome to you,' he cried. '<strong>The</strong>Blacks and the whites, the Greek andthe Jew, we're all children of Jesus.' Hesaw me as an outsider like them. Ithelped us communicate."<strong>The</strong> service was a heady experiencefor Greene and other GLSP staffers."People were there, packing the pews,singing and strategizing afterwards. Itwas the Civil Rights movement I hadread about in other places. Here, 10,20years later, I was participating in it."By this time, however, Greene, wasliving in Savannah, was experiencinga powerful, simultaneous, call toher original vocation — writing. "Ibegan to work on full-length, nonfictionarticles in the evenings afterwork," she wrote in an article called"<strong>On</strong> Writing Nonfiction." "It wasas if the city, Savannah, presseditself full-length against my windowsat night, palm trees blowing,cicadas whirring, cars honking, andrather than keep it at bay in order tocreate fictional worlds, I opened mynotebooks to it. I interviewed peopleI'd met through work — elderly Blackand white clients, mostly — and wroteMy maininterestin school hadbeen history,Southernhistory andintellectuallyunderstandingslaveryportraits of them, reconstructing,through their memories, Savannahin the 1930s, the 1910s, the 1890s.My oldest subjects were still immersedin worlds now all but extinct."Those worlds spanned much of thestate, and introduced her to a widerange of people. In Mclntosh County,for example, there was Miss Fanny, oneof the area's most colorful and respectedBlack matriarchs, who spoke her ownbrand of English seasoned with Gullah,an oral language whose masters have,until recently, eschewed recording it."She would talk about going into placesthat had this thing, a picolo, whichmeant a jukebox. She would screamwith laughter when I asked what particularwords meant. <strong>The</strong>n there werethe stories involving buckets of guano,"which Greene eventually came to understandas chickenshit fertilizer."I had done the research, interviewingpeople in Mclntosh County, when I wassingle and childless. I worked on it onand off. I did it originally to capture thevoices, and the moment I took themdown I knew I'd get them out into theworld someday. I knew I had a treasureof interviews stored in boxes in my basement,"she says.Still, by 1988, when Green started topull together the material that wouldeventually become Praying forSheetrock, she was a wife and the motherof three daughters. (She is currentlypregnant again, due in late May.) "Ireally like the chaos of children underfoot,the constant creativity, but at thesame time writing is a way to straightenthings up, a way to order the chaos,away to sweep the Legos under thebedcovers."<strong>The</strong> children have forced me to focus.Before I had children, I used to readpoetry and slowly build up to the momentof writing. Now, the minute they'reout of the house I sit down to write. It'skept the writing fresh for me, it's thework I can't wait to sit down and do, arace against the clock."Now that writingPraym,g/or Sheetrockis behind her, Greene devotes her timeto articles and more manageable, shorttermprojects. Meanwhile, she maintainsregular contact with the manywomen and men whose stories makeSheetrock such a memorable, importantbook. Recently, in fact, when she andher children were paying the Alstons avisit, the entire Greene clan got anotherlesson in the ways of Mclntosh County.Warning Becca Alston that her oldesttwo children had just been exposed tochicken pox, she was shocked to seeBecca lead her three daughters into herchicken coop. <strong>The</strong>re, she proceeded "toscare the daylights out of them by shooingchickens at them. <strong>The</strong> country curefor chicken pox, it seemed, was to causea chicken to fly directly over a child'shead. It proved to be an ineffective cure,although diverting."Sharing life experiences, getting pastrace and class and truly communicating,truly listening, is what Greene'swork is all about. And while MclntoshCounty 1992 is still far from an idyllicplace to live, the capturing of the voicesand ways of its residents provides aliving testament to human resilienceand the struggle for dignity. •38 ON THE ISSUES SUMMER 1992

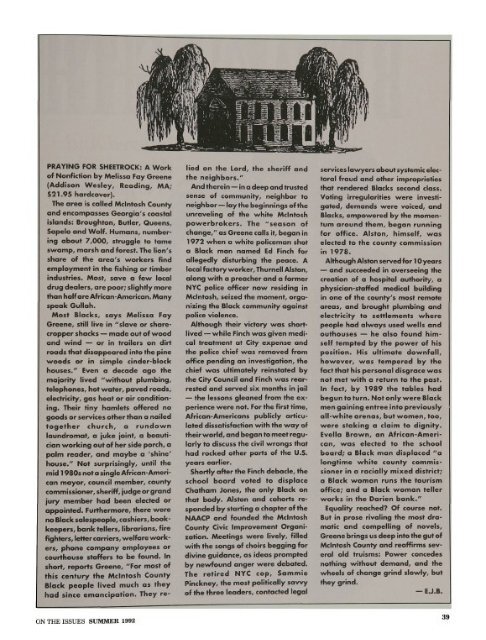

PRAYING FOR SHEETROCK: A Workof Nonfiction by Melissa Fay Greene(Addison Wesley, Reading, MA;$21.95 hardcover).<strong>The</strong> area is called Mclntosh Countyand encompasses Georgia's coastalislands: Broughton, Butler, Queens,Sapelo and Wolf. Humans, numberingabout 7,000, struggle to tameswamp, marsh and forest. <strong>The</strong> lion'sshare of the area's workers findemployment in the fishing or timberindustries. Most, save a few localdrug dealers, are poor; slightly morethan half are African-American. Manyspeak Gullah.Most Blacks, says Melissa FayGreene, still live in "slave or sharecroppershacks — made out of woodand wind — or in trailers on dirtroads that disappeared into the pinewoods or in simple cinder-blockhouses." Even a decade ago themajority lived "without plumbing,telephones, hot water, paved roads,electricity, gas heat or air conditioning.<strong>The</strong>ir tiny hamlets offered nogoods or services other than a nailedtogether church, a rundownlaundromat, a juke joint, a beauticianworking out of her side porch, apalm reader, and maybe a 'shine'house." Not surprisingly, until themid 1980s not a single African-Americanmayor, council member, countycommissioner, sheriff, judge or grandjury member had been elected orappointed. Furthermore, there wereno Black salespeople, cashiers, bookkeepers,bank tellers, librarians, firefighters, letter carriers, welfare workers,phone company employees orcourthouse staffers to be found. Inshort, reports Greene, "For most ofthis century the Mclntosh CountyBlack people lived much as theyhad since emancipation. <strong>The</strong>y reliedon the Lord, the sheriff andthe neighbors."And therein — in a deep and trustedsense of community, neighbor toneighbor — lay the beginnings of theunraveling of the white Mclntoshpowerbrokers. <strong>The</strong> "season ofchange," as Greene calls it, began in1972 when a white policeman shota Black man named Ed Finch forallegedly disturbing the peace. Alocal factory worker, Thurnell Alston,along with a preacher and a formerNYC police officer now residing inMclntosh, seized the moment, organizingthe Black community againstpolice violence.Although their victory was shortlived— while Finch was given medicaltreatment at City expense andthe police chief was removed fromoffice pending an investigation, thechief was ultimately reinstated bythe City Council and Finch was rearrestedand served six months in jail— the lessons gleaned from the experiencewere not. For the first time,African-Americans publicly articulateddissatisfaction with the way oftheir world, and began to meet regularlyto discuss the civil wrongs thathad rocked other parts of the U.S.years earlier.Shortly after the Finch debacle, theschool board voted to displaceChatham Jones, the only Black onthat body. Alston and cohorts respondedby starting a chapter of theNAACP and founded the MclntoshCounty Civic Improvement Organization.Meetings were lively, filledwith the songs of choirs begging fordivine guidance, as ideas promptedby newfound anger were debated.<strong>The</strong> retired NYC cop, SammiePinckney, the most politically savvyof the three leaders, contacted legalservices lawyers about systemic electoralfraud and other improprietiesthat rendered Blacks second class.Voting irregularities were investigated,demands were voiced, andBlacks, empowered by the momentumaround them, began runningfor office. Alston, himself, waselected to the county commissionin 1978.Although Alston served for 10 years— and succeeded in overseeing thecreation of a hospital authority, aphysician-staffed medical buildingin one of the county's most remoteareas, and brought plumbing andelectricity to settlements wherepeople had always used wells andouthouses — he also found himselftempted by the power of hisposition. His ultimate downfall,however, was tempered by thefact that his personal disgrace wasnot met with a return to the past.In fact, by 1989 the tables hadbegun to turn. Not only were Blackmen gaining entree into previouslyall-white arenas, but women, too,were staking a claim to dignity.Evella Brown, an African-American,was elected to the schoolboard; a Black man displaced "alongtime white county commissionerin a racially mixed district;a Black woman runs the tourismoffice; and a Black woman tellerworks in the Darien bank."Equality reached? Of course not.But in prose rivaling the most dramaticand compelling of novels,Greene brings us deep into the gut ofMclntosh County and reaffirms severalold truisms: Power concedesnothing without demand, and thewheels of change grind slowly, butthey grind.— EJ.B.ON THE ISSUES SUMMER 199239