Are China's Financial Reforms Leaving the Poor Behind - Harvard ...

Are China's Financial Reforms Leaving the Poor Behind - Harvard ...

Are China's Financial Reforms Leaving the Poor Behind - Harvard ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Draft August 2001<strong>Are</strong> China’s <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Reforms</strong> <strong>Leaving</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Poor</strong> <strong>Behind</strong>?Loren BrandtDepartment of Economics, University of TorontoAlbert ParkJFK School of Government, <strong>Harvard</strong> UniversityDepartment of Economics, University of MichiganWang SanguiInstitute of Agricultural Economics, Chinese Academy of Agricultural SciencesPaper prepared for <strong>the</strong> conference on“<strong>Financial</strong> Sector Reform in China”JFK School of Government, <strong>Harvard</strong> UniversitySeptember 11-13, 20012

<strong>Are</strong> China’s <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Reforms</strong> <strong>Leaving</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Poor</strong> <strong>Behind</strong>?1. IntroductionSince economic reforms began, <strong>the</strong> Chinese state has shifted <strong>the</strong> locus of controlover <strong>the</strong> allocation of resources from <strong>the</strong> fiscal to <strong>the</strong> financial ledger (Sehrt, 1999).Under <strong>the</strong> planning system, funds were mobilized by setting prices to concentrate profitsin state-owned industry (Naughton, 1995). During <strong>the</strong> reform period, market competitioneroded <strong>the</strong> profitability of SOEs, and <strong>the</strong> government struggled to establish an effectivetaxation system to generate revenue (Wong, Heady, and Woo, 1995). However, byasserting its control over <strong>the</strong> banking system, <strong>the</strong> state was able to continue directingnational resources to support its most important political constituency--urban workers instate-owned enterprises (Brandt and Zhu, 2000). This strategy was facilitated by <strong>the</strong>rapid growth of individual private savings in state-owned banks, which have come todominate China’s national savings (Kraay, 2000). 1The financial system has increasinglybecome <strong>the</strong> key mechanism by which <strong>the</strong> government attempts to realize its distributionalgoals.Government allocation of resources in China as well as in many o<strong>the</strong>r developingcountries has been biased against rural areas and in favor of urban areas, undoubtedlywidening urban-rural disparities (Putterman, 1992; Park and Rozelle, 1998; Lipton,1984). Transfers through <strong>the</strong> banking system are only one aspect of this urban bias,which also includes extraction of taxes, fees, pricing policy, procurement quotas, and1 According to official data, most of <strong>the</strong> increase in deposits was by urban residents, although <strong>the</strong> urbanruraldistinction is not always clear because rural residents may deposit funds in any bank. In 1998, <strong>the</strong>percentage of individual deposits from rural areas (defined as deposits in Rural Credit Cooperatives) was20 percent, compared to 26 percent in 1990. Urban deposits in 1998 were 8.1 times that in 1990, ruraldeposits were 5.7 times as great. On a per capita basis, <strong>the</strong> deposits of urban residents in 1998 were nearly10 times that of rural residents. Individual deposits accounted for 55 percent of all deposits in all financialinstitutions in 1999, with <strong>the</strong> second largest category being enterprise deposits (34 percent).3

analyze changes in <strong>the</strong> degree of financial intermediation by rural financial institutions inrich and poor areas. This is an important question because it addresses <strong>the</strong> keyefficiency-equity tradeoff of market reform. It is now well-established that financialintermediation plays an important role in growth, so that current allocations of financialresources shape future patterns of inequality (Gertler and Rose, 1996; Levine, 1997; Kingand Levine, 1993; Levine and Zervos, 1998; and Rajan and Zingales, 1998). Givenrapidly rising regional income inequality in China and <strong>the</strong> concern shared by many thatcredit access is a key constraint to development in China’s poorest areas, betterunderstanding of <strong>the</strong> distributional consequences of financial reform takes on addedimportance. This is especially true given <strong>the</strong> lack of any systematic empirical study ofthis issue.In this paper, we study changes in financial intermediation and financialperformance over time using a unique data set from surveys of rural financial institutionsconducted by <strong>the</strong> authors in two rich, coastal provinces (Zhejiang and Jiangsu) and in twopoor, interior provinces (Sichuan and Shanxi) in 1998 and 1999. The paper focuses on<strong>the</strong> financial role played by <strong>the</strong> two main rural financial institutions in China and ourresults should be qualified by an awareness that we do not consider informal borrowingor lending and saving in o<strong>the</strong>r formal or informal financial institutions. However,informal networks tend to be segmented and fragmented, and informal organizations thatreach large scale have not been tolerated. We <strong>the</strong>refore believe <strong>the</strong> role of ABC branchesand RCCs to be pivotal in achieving effective financial intermediation in rural areas.Focusing on rural financial institutions has several motivations. First, rural Chinaremains home of 70 percent of China’s population. Rural financial institutions are <strong>the</strong>6

highest in Zhejiang (4470 yuan), followed by Jiangsu (3650 yuan), Sichuan (2060 yuan)and Shanxi (1558 yuan). 5In each province, a representative sample of counties was selected from differentregions of <strong>the</strong> province and in areas with different levels of economic and industrialdevelopment. Eight counties were selected in Jiangsu, seven in Zhejiang, and six in bothSichuan and Shanxi. Within each county, four townships were randomly selected afterstratifying by industrial output per capita. In total, 108 townships in 27 counties werechosen, and all ABC branches and RCCs in <strong>the</strong>se townships were surveyed. Not alltownships have ABC branches so <strong>the</strong> sample of ABC branches is smaller than <strong>the</strong> sampleof RCCs. In each county, separate interviews also were conducted with <strong>the</strong> county ABCbranch and <strong>the</strong> county RCC association, <strong>the</strong> headquarter banks for township ABCbranches and RCCs. In each township, additional interviews were conducted withgovernment officials and a sample of enterprise managers.Most of <strong>the</strong> information was garnered from face-to-face interviews with bankmanagers, and available historical data on assets, liabilities, income, and expenditureswere copied from accounting books. The survey focused on <strong>the</strong> period between 1994 and1997. Because <strong>the</strong> surveys in Sichuan and Shanxi were conducted a year later, anadditional year of data was collected (for 1998).The data have several unique features. First, <strong>the</strong> data cover a period of majorreform in China’s financial system and in <strong>the</strong> operation of China’s rural financialinstitutions. Second, <strong>the</strong> surveys provide for <strong>the</strong> first time very detailed information onfinancial performance, regulation, and governance of China’s rural financial institutions,5 The 1998 China Statistical Yearbook reports 1997 rural income (living expenditures) per capita of 3684(2839) yuan in Zhejiang, 3270 (2488) yuan in Jiangsu, 1681 (1440) yuan in Sichuan, and 1738 (1145) yuanin Shanxi.9

which is of great interest to those concerned about China’s rural credit markets andChina’s broader financial system reform. Third, <strong>the</strong> surveys in rich and poor provincesprovides an excellent basis for a regional comparison of financial performance and bankbehavior, facilitating a study of <strong>the</strong> distributional consequences of financial reform.3. <strong>Financial</strong> reform and China’s rural financial institutionsChina’s two main rural financial institutions, <strong>the</strong> Agricultural Bank of China(ABC, or nongye yinhang) and Rural Credit Cooperatives (RCCs, or xinyongshe),accounted for 14 and 13 percent of deposits in all financial institutions in 1998 and 16and 10 percent of all lending. Thus, toge<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>y account for more than one fourth of alldeposits and loans in China. 6The ABC is one of China’s four specialized banks, with <strong>the</strong>largest branch network among specialized banks, extending to most but not alltownships. 7Most lending is working capital loans for state commercial enterprises, butsignificant shares also are lent to township and village enterprises (TVEs), 8 and toagriculture (including households). The RCCs are cooperatives in name only (not ingovernance). Since 1996, <strong>the</strong>y have been under <strong>the</strong> administrative supervision of <strong>the</strong>Peoples Bank of China (previously under <strong>the</strong> ABC). RCCs are <strong>the</strong> only financialinstitutions with branch outlets extending to nearly all townships as well as many6 Until 1999, rural cooperative foundations (RCFs, or nongcun hezuo jijinhui) could also be found in manytownships, especially in richer areas (38 percent of all townships in 1996). The RCFs were quasigovernmentorganizations under <strong>the</strong> administrative supervision of <strong>the</strong> Ministry Agriculture. In 1996, RCFdeposits were estimated to be one ninth that of RCCs. A national survey found that 24 percent of RCFloans went to TVEs and 45 percent to households. RCFs often had significant involvement of townshipofficials, lack legal status as financial institutions, and often charged effective interest rates above regulatedrates. Following a 1998 State Council circular, <strong>the</strong>y were dissolved in 1999.7 The Agricultural Development Bank of China (ADBC, or nongye fazhan yinhang) separated from <strong>the</strong>ABC as one of three policy banks established in 1994, with branches at <strong>the</strong> county level. In 1996, <strong>the</strong>ADBC accounted for 10 percent of national lending. Ninety percent of loans were for agriculturalprocurement, mainly grain.8 Following Chinese conventions, we define TVEs to include both collective and private enterprises.10

villages. They are by far <strong>the</strong> most important source of formal credit in rural areas,providing over half of all loans to rural enterprises but lending also to households.Before examining <strong>the</strong> performance of local ABC branches and RCCs, we firstintroduce relevant aspects of <strong>the</strong> political, economic, and regulatory environment forlending. First, although most policy loans in <strong>the</strong> rural sector (mainly for agriculturalcommodity procurement) were transferred to <strong>the</strong> Agricultural Development Bank ofChina (ADBC), ABC branches and RCCs were not immune to local political pressures,especially from local government officials keen to support revenue-generating industrialprojects. ABCs also carry a small portfolio of explicit policy loans (including povertyalleviation loans) and may be asked to support state marketing agencies. None<strong>the</strong>less,most managers in both institutions report that profitability has been <strong>the</strong> most importantcriteria for approving loans even by 1994. This commercial orientation increasedsteadily over time, so that by 1997 profits had overwhelming become <strong>the</strong> main statedconcern of bankers (Park and Shen, 2000). In recent years, managerial pay has beenmore closely tied to profits through a higher share of income paid in <strong>the</strong> form of bonuses.Overall, we should expect less policy lending in rural financial institutions than in o<strong>the</strong>rlarge specialized banks and policy banks, and for policy lending to decline over time.Second, despite efforts to increase profit incentives, most bank managers operatein a highly circumscribed regulatory environment. All deposit and lending interest ratesare controlled at below-market clearing levels, adjustable by small margins. Also, interbankloans are regulated both in terms of quantity and price. After a frenzy ofuncontrolled inter-bank lending in <strong>the</strong> early 1990s, <strong>the</strong> government shut down <strong>the</strong> interbankmarket in 1993. Currently, most transfers of financial resources are through vertical11

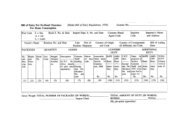

deposits of surplus funds in higher level branches of <strong>the</strong> same bank. Thus, townshipABC branches deposit funds with <strong>the</strong> county ABC branch, and RCCs deposit funds with<strong>the</strong> county RCC association (lianhehui). The ABC is a national bank, but transfersamong RCCs typically occur only among branches within <strong>the</strong> same counties. Many bankmanagers have an approved credit quota based on a county plan or on an agreementlinking lending amounts to <strong>the</strong> amount of deposits. In most cases, <strong>the</strong> quota can beadjusted if <strong>the</strong> manager can justify <strong>the</strong> need for more funds. Managers also are oftenrestricted in <strong>the</strong> size of loans that can be issued without approval from <strong>the</strong> county ABCbranch or RCC association, and local discretion in individual loan decisions hasdecreased over time (Shen and Park, 2001). The county banks play an important role inregulating and supervising township bank branches, although <strong>the</strong> township banks remainindependent accounting units. Managers have almost no options for fund use o<strong>the</strong>r thanlocal lending and deposits in higher level banks. The internal interest rates for suchdeposits (usually set very low), <strong>the</strong> credit quota, and <strong>the</strong> riskiness of local projects thusare major factors affecting loan allocation decisions.In Table 1, we provide summary balance sheet information from <strong>the</strong> ruralfinancial institutions we surveyed. Dependence on deposits as a source of fundsincreased from 58 percent in 1994 to 64 percent in 1997, suggesting a decline ra<strong>the</strong>r thanan increase in interbank lending. This dependence is particular high, and growing in poorareas, suggesting that deposit mobilization may play an important role in determining <strong>the</strong>amount that financial institutions in such areas can lend. The overall size of <strong>the</strong> financialinstitutions, as measured by total assets, is nearly ten times as great in <strong>the</strong> richest quartile12

of regions than in <strong>the</strong> poorest quartile. The rural financial institutions in Zhejiang areparticularly large, and ABC branches are considerably bigger than RCCs.Most rural lending is to firms, not farmers. Seventy-four percent of outstandingloans went to firms in 1994; by 1997 <strong>the</strong> share had fallen slightly to 71 percent (Table 1).However, in poorest quartile where presumably <strong>the</strong>re are few viable enterprises, less than40 percent of loans go to enterprises. RCCs, which in general lend more to firms, 83percent in 1994, are reducing <strong>the</strong>ir loans to firms while ABC branches are increasing<strong>the</strong>m. There is also a movement in coastal areas to increase lending to privateenterprises, due in large part to rapid privatization of collective enterprises during <strong>the</strong>mid-1990s (data not presented).For Sichuan and Shanxi, we have a more detailed breakdown of lendingcategories (Appendix Table 1). Enterprise lending is predominant in Sichuan whilehousehold lending is dominant in Shanxi. Household lending also comprises a muchhigher share of lending in poorer townships (over two thirds in <strong>the</strong> poorest quartile in1998), no doubt due in part to <strong>the</strong> lack of enterprises in such areas. Except for in <strong>the</strong>richest quartile, a greater share of loans went to households in 1998 than in 1994. In <strong>the</strong>richest quartile, lending in 1998 is marked by greater firm lending. Also, loans toagriculture and o<strong>the</strong>r loans declined in poor townships but not rich townships. Finally,RCCs lend a much greater share of funds to enterprises than ABCs. This is likely due tosignificant lending by ABCs to marketing agencies such as supply and marketingcooperatives (gongshaoshe) and grain trading companies (liangshi maoyi gongsi).Overall, we observe a greater willingness of financial institutions to lend tohouseholds in poorer townships, and that this relative tendency has become greater over13

time. This is not to say that households found it easier in 1997 than in 1994 to obtainloans, as total lending declined over this period. These findings are consistent with o<strong>the</strong>rresearch showing that a relatively high proportion of farmers in poor regions have at leastsome access to formal credit (Park and Wang, 2000). 9Ironically, it may be households inricher areas that have greater difficulty obtaining individual loans because banks so preferlending to enterprises. However, richer households have greater savings (and deposits)and so generally are more able to self-finance common expenditures such as for fertilizerand school fees. From this perspective, household credit demand does not necessarilyrise with income, unless rural residents shift to self-employment activities that requiregreater financing.4. Changes in financial intermediation in rich and poor areas from 1994 to 1997<strong>Financial</strong> intermediationTo assess whe<strong>the</strong>r China’s financial reforms are leaving <strong>the</strong> poor behind, werequire a financial performance measure that will enable us to compare <strong>the</strong> extent offinancial intermediation in rich versus poor areas over time. <strong>Financial</strong> development isfrequently measured by <strong>the</strong> amount of financing normalized by <strong>the</strong> value of economicoutput, e.g., <strong>the</strong> ratio of total loans to GDP. In this paper, we restrict attention to formalfinancial intermediation in <strong>the</strong> form of credit, excluding equity financing and informal9 One piece of supporting evidence for unmet household credit demand was <strong>the</strong> success of RuralCooperative Foundations (RCFs, or nongye hezuo jijinhui) in <strong>the</strong> 1990s. These quasi-formal institutions,under <strong>the</strong> administrative jurisdiction of <strong>the</strong> Ministry of Agriculture, tended to be established in moreindustrial areas and lent mainly to households. However, <strong>the</strong>re is also evidence that <strong>the</strong>y merely crowdedout household lending by incumbent RCCs and so did not increase overall household lending (Park, Brandt,and Giles, 2000). RCFs were banned by <strong>the</strong> government in 1999.14

orrowing. 10A consistent finding in cross-country studies is that <strong>the</strong> level ofdevelopment as measured by GDP per capita is positively associated with <strong>the</strong> degree offinancial depth (Gertler and Rose, 1996). Park and Sehrt (forthcoming), however, findthat this relationship does not hold for provinces in China, implying regional barriers toefficient intermediation.Because GDP is not calculated at <strong>the</strong> township level in China, we adopt adifferent measure--<strong>the</strong> ratio of outstanding loans per capita to rural income per capita.Income per capita is a net ra<strong>the</strong>r than gross measure and does not include retainedearnings in enterprises or o<strong>the</strong>r income that does not accrue to households. It is expectedto be highly correlated with, but to rise less than proportionally with GDP. Relative to ameasure using GDP, this could lead us to overstate <strong>the</strong> relationship between <strong>the</strong> level ofdevelopment and depth of financial intermediation.We also make a second adjustment. Many banks in China have large amounts ofoverdue loans with dubious repayment prospects. If loans that should be written off aslosses are kept on <strong>the</strong> books, <strong>the</strong>y can present a misleading picture of <strong>the</strong> true extent offinancial intermediation and net flow of funds. Fortunately, our survey providesinformation on overdue, or non-performing loans. We can thus divide total outstandingloans into “performing” and “non-performing” loans. Even though some overdue loanscould be providing a meaningful intermediation function, we consider <strong>the</strong> amount ofperforming loans relative to income to be a superior measure of effective financialintermediation. We report financial intermediation rates using both total outstandingloans and performing loans (Table 2).10 During this period, TVEs could not be listed in capital markets. Informal borrowing is probably at leastas important as formal financing for households in rural areas (Brandt, Giles, and Park, 1997) but relativelyunimportant for firms.15

We find that from 1994 to 1997 <strong>the</strong> extent of financial intermediation stayed <strong>the</strong>same in terms of total loans but actually fell in terms of performing loans. Even usingtotal loans, <strong>the</strong> data show that richer provinces (Zhejiang and Jiangsu) and richertownships witness no clear change from 1994 to 1997 but that <strong>the</strong> poorer provinces(Sichuan and Shaanxi) and townships show a slight reduction in intermediation.Comparing <strong>the</strong> ratio of performing loans to income in 1994 and 1997, <strong>the</strong>se differencesare much more pronounced, with <strong>the</strong> fall in intermediation in poor areas quite sharp(from 0.30 to 0.23 in <strong>the</strong> poorest quartile), and continuing into 1998. The annualreduction in performing loans relative to income is 13 percent in poorest quartile areasbut only one percent in <strong>the</strong> richest quartile. There is some evidence that intermediationby ABCs is increasing but that by <strong>the</strong> RCCs is decreasing.To see clearly <strong>the</strong> different factors that influence <strong>the</strong> extent of effective financialintermediation in a locality, we decompose our financial intermediation rate in <strong>the</strong>following way:PL PL L D= x x , (1)Y L D YwherePL is performing loans,Y is income,L is total outstanding loans, andD is deposits.The rate of effective financial intermediation is <strong>the</strong> product of <strong>the</strong> share of performingloans in total loans, <strong>the</strong> loan to deposit ratio, and <strong>the</strong> ratio of deposits to income. Thesethree variables measure loan performance, net fund flows, and deposit mobilization,16

espectively. In <strong>the</strong> following sections, we review <strong>the</strong> empirical evidence on changes ineach of <strong>the</strong>se factors, highlighting differences between rich and poor areas. We <strong>the</strong>nsummarize <strong>the</strong> relative importance of each factor in explaining changes in intermediationover time.Loan PerformanceNon-performing loans include three categories: overdue, inactive (overdue formore than 2 years), and dead (overdue for more than 3 years or confirmed for o<strong>the</strong>rreasons to be unrecoverable). Most non-performing loans fall in <strong>the</strong> first category butnearly half fall in <strong>the</strong> two more delinquent categories. Overall, <strong>the</strong> share of outstandingloans that are overdue in <strong>the</strong> full sample rises from 17 percent in 1994 to 24 percent in1997 (Table 3). However, <strong>the</strong> overdue rates are substantially higher in poorerprovinces. 11In Sichuan, overdues increase from 25 to 32 percent, and in Shanxi, <strong>the</strong>yrise from 30 to 40 percent. In 1998, <strong>the</strong> percent of outstanding loans overdue stabilizes to28 percent in Sichuan but continues on an upward trajectory in Shanxi, reaching 48percent. Such repayment rates are financially unsustainable if banks are to remainsolvent without major infusions of outside capital. And <strong>the</strong>y may understate <strong>the</strong> truemagnitude of <strong>the</strong> repayment problem if banks roll over loans through “evergreening” oro<strong>the</strong>rwise conceal repayment problems (Lardy, 1998).These percentages of non-performing loans appear comparable to <strong>the</strong> 22 percentfigure cited by Lardy (1998) for China’s four large state-owned banks in 1995. We alsocan compare <strong>the</strong> overdue rates to those found in o<strong>the</strong>r surveys. The 1996 national village11 The full sample average reflects <strong>the</strong> greater number of financial institutions surveyed in <strong>the</strong> coastalprovinces and <strong>the</strong> greater amount of funds per financial institution.17

survey found an average overdue rate in 1995 of 21 percent and <strong>the</strong> CRPS survey foundan average overdue rate in 1996 of 39 percent. These results are roughly consistent withour estimates of <strong>the</strong> non-performing loans in <strong>the</strong> 4 sample provinces, and reinforce ourfinding that repayment problems are significant everywhere but substantially worse inpoorer regions.However, although <strong>the</strong> levels of overdues are greater in poorer townships, <strong>the</strong> rateof increase in overdues is as rapid in Zhejiang, 8 percent, and in <strong>the</strong> richest quantile oftownships, 12 percent, as in poorer provinces and townships. As a percentage of <strong>the</strong>initial share of bad loans, <strong>the</strong> increase is most rapid in <strong>the</strong> richest quartile, 32 percent peryear, followed by <strong>the</strong> poorest quartile at 14 percent. The bad loan problem striking ruralfinancial institutions in China’s coastal areas is <strong>the</strong> result of poor bank governance(incentives of managers) in some areas, <strong>the</strong> deteriorating profitability of rural enterprises,and <strong>the</strong> increasing frequency of strategic default on loans (Park and Shen, 2000). Theseproblems may be related to overall slower growth, intensifying market competition, andunrealistic over-investment in <strong>the</strong> early 1990s.We also note that <strong>the</strong> deterioration in loan performance appears to be greater forRCCs than ABC branches, and that based on data from Sichuan and Shanxi <strong>the</strong>deterioration is very sharp for TVEs but nonexistent for household loans (typically foragricultural production or self-employment). In Sichuan and Shaanxi, by 1997 nonperformingloans accounted for 38 percent of outstanding TVE loans compared to 23percent in 1994. Meanwhile, overdue household loans were stable at 32 and 33percent(Table 4).18

<strong>Are</strong> funds flowing out of poor areas?We measure <strong>the</strong> net flow of funds by <strong>the</strong> ratio of outstanding loans to deposits ineach financial institution. A financially self-sufficient bank should have a loan-depositratio less than one because of reserve requirements (13 percent nationally but higher forsome local branches, especially RCCs before 1996 when <strong>the</strong>y were regulated by ABCs).Higher loan-deposit ratios imply that more local resources are being lent locally ra<strong>the</strong>rthan being intermediated for use in o<strong>the</strong>r areas, such as through bank deposits inheadquarter banks or o<strong>the</strong>r banks, or through inter-bank lending. 12If funds tend to flowout of poor areas, we would expect such areas to have lower loan-deposit ratios. Banksborrowing funds from <strong>the</strong>ir headquarters or from o<strong>the</strong>r banks could have loan depositratios exceeding one.Table 4 presents loan-deposit ratios broken down by province, income per capitaquartile, and bank type. Overall, more funds flowed out of rural areas in 1997 than in1994, as evidenced by <strong>the</strong> fall in <strong>the</strong> average loan-deposit ratio for <strong>the</strong> full sample from0.71 to 0.64. For all financial institutions nationwide, <strong>the</strong> ratio of loans to deposits fellfrom 1.01 to 0.91 over this same period (State Statistical Bureau, 1999). 13Thus, ruralareas consistently are net contributors of resources for lending elsewhere, but <strong>the</strong> degreeof this bias did not shift significantly in <strong>the</strong> mid-1990s. These loan-deposit ratios aresimilar to those found in a 1996 national survey of 94 RFIs in six provinces and in <strong>the</strong>1997 China Rural Poverty Survey conducted in six poor national poor counties in12 In addition to deposits, funds can come from <strong>the</strong> bank’s own capital, net borrowing, and o<strong>the</strong>r sources.Because we are unable to clearly separate o<strong>the</strong>r sources and uses of funds into those that originate or areinvested locally and those that are borrowed from or invested elsewhere, we treat deposits and loans as <strong>the</strong>only purely local source and use of funds. A better measure of net outflow would account for all sourcesand uses of funds.13 The high loan-deposit ratios for all banks and ist subsequent decline largely reflect relending by <strong>the</strong>People’s Bank of China to state-owned banks, which through <strong>the</strong> 1980s accounted for as much as 30percent of funds, but since <strong>the</strong> mid-1990s has tightened considerably.19

different provinces, both conducted by <strong>the</strong> authors (Table 5). The national village surveyfound a sharp reduction in loan to deposit ratios from 0.94 in 1988 to 0.68 in 1994(recovering to 0.73 in 1995), while <strong>the</strong> CRPS finds a smaller but still large fall from 0.73in 1988 to 0.61 in 1994 and a continued decline to 0.54 in 1996.The loan-deposit ratios in poorer townships are lower than in richer townships(Table 4), and <strong>the</strong> mean ratio in <strong>the</strong> CRPS is lower than in <strong>the</strong> national village survey(Table 2). However, <strong>the</strong> differences among provinces are not significant in 1994. <strong>Poor</strong>areas likely have a more difficult time attracting outside funds and bank managers mayalso have a greater reluctance to lend <strong>the</strong>ir own funds locally. Table 1 reports <strong>the</strong> shareof total funds that are deposits. Two strong patterns emerge. The first is that poorerareas are much more reliant on <strong>the</strong>ir own deposits than richer areas. The second is thatall areas are more reliant on own deposits in 1997 than in 1994. Credit tightened in <strong>the</strong>financial retrenchment period beginning in 1994, and a new emphasis was placed on loanquality.Among provinces, <strong>the</strong> decrease in <strong>the</strong> loan-deposit ratio is largest in Jiangsu (14percent), while Shanxi’s loan-deposit ratio actually increases slightly (by 3 percent, Table4). It appears that over time funds are less, not more likely, to flow into richer provinces!The pattern is even more striking if we look at <strong>the</strong> change in loan-deposit ratios byincome quartile. The loan-deposit ratio fell by fiver percent in <strong>the</strong> richest quartile andgrew by five percent in <strong>the</strong> poorest quartile. <strong>Are</strong> projects better in poorer areas? Or arebranches in richer townships being “taxed” by state financial institutions to mobilizefunds for use elsewhere? The latter explanation hardly seems consistent with China’scommercialization reforms.20

Deposit and Income GrowthBoth deposits and incomes grew rapidly in rural China from 1994 to 1997, aperiod of higher commodity prices and healthy output growth. Deposits grew by 12percent per year and rural incomes grew by 11 percent (Table 6). While average growthin real incomes was similar across provinces over <strong>the</strong> three-year period (1994 to 1997),poorer townships grew substantially faster than richer townships. Income per capita in<strong>the</strong> richest quartile of townships increases by 7 percent per year while in <strong>the</strong> poorest itgrew by 13 percent. This is consistent with <strong>the</strong> convergence hypo<strong>the</strong>sis of <strong>the</strong>neoclassical growth model, and suggests we may be mistaken to assume that goodprojects do not exist in poor areas. However, despite lower income growth, <strong>the</strong> depositgrowth rate is higher among <strong>the</strong> higher income groups (13 percent in <strong>the</strong> richest quartileand 8 percent in <strong>the</strong> poorest). These differences are consistent with a greater propensityto save with higher income. Loans grow even more slowly than deposits, and nonperformingloans grow faster in both <strong>the</strong> richest and poorest quartiles. The poorest areasare thus characterized by high income growth (13 percent), low deposit growth (8percent), even lower loan growth (7 percent), and lower growth still in performing loans(minus one percent) because of <strong>the</strong> rapid growth of non-performing loans. Realperforming loans for <strong>the</strong> poorest quartile is slightly negative even though real incomesare growing fast. Overall, <strong>the</strong> results suggest failing intermediation in poor areas drivenby a failure of available resources to keep up with income growth and high amounts ofnon-performing loans. Richer areas have more room to maneuver because <strong>the</strong>y can moreeasily mobilize deposits, but here too, poor loan performance is undermining <strong>the</strong> ability21

of banks to provide new loans. The richest quartile has moderate income growth (7percent), high deposit growth (13 percent), moderate total loan growth (9 percent) butlow growth in performing loans (2 percent).The very uneven growth in deposits in rich and poor areas explains <strong>the</strong> apparentlyinconsistent earlier findings that <strong>the</strong> loan-deposit ratios are falling in rich areas but notpoor areas, but that financial intermediation (loans/income) is holding steady in rich areasbut falling in poor areas. The change in fund flow or loan repayment is not obviouslyworse in poor areas, but deposit growth is not keeping up with income growth, whereasin rich areas deposit growth is far exceeding income growth.Decomposing <strong>the</strong> sources of change in financial intermediationFrom (1), it is straightforward to decompose <strong>the</strong> rate of change in effectivefinancial intermediation as <strong>the</strong> sum of <strong>the</strong> growth rates of its components:PLlog(Y9797PL94PL97PL94L97L94) − log( ) = {log( ) − log( )} + {log( ) − log( )} (2)Y L L D D9497{log( D97 ) − log( D94)} + {log( Y97) − log( Y94)}949794The difference in logs for each variable is equal to <strong>the</strong> exponential growth rate, which canbe annualized by dividing by <strong>the</strong> number of years. Table 7 summarizes <strong>the</strong> growth ratesin (2) and reports <strong>the</strong> percentage of <strong>the</strong> overall rate of change in effective financialintermediation accounted for by each factor.The results confirm <strong>the</strong> earlier findings that much of <strong>the</strong> relative deterioration ofeffective intermediation in poor areas is due to poor loan repayment and a failure to22

mobilize deposits even as income rise. Of <strong>the</strong> 13 percent annual fall in effectiveintermediation rates in <strong>the</strong> poorest quartile during <strong>the</strong> period, loan performance accountsfor 10 percent, <strong>the</strong> loan to deposit ratio–5 percent (it increases), and increasing depositsrelative to deposits accounts for 5 percent.We also estimate a set of regressions of financial performance indicators on <strong>the</strong>log of real income per capita, comparing <strong>the</strong> results for 1994 and 1997 (Table 8).Because of our concern that differences between rich and poor provinces may be drivenby differences in provincial policies or o<strong>the</strong>r unobserved provincial characteristics ra<strong>the</strong>rthan income differences, we run <strong>the</strong> regressions with and without controls for provincialdifferences. In all regressions, we control for differences in bank type. To control forboth provincial differences and bank type, we include dummy variables which areinteractions of province and bank type dummies. This specification is very general inthat it allows bank type to have different effects in different provinces, and <strong>the</strong> effects ofincome per capita are identified by variation among banks of <strong>the</strong> same type in <strong>the</strong> sameprovince.The results confirm many of <strong>the</strong> previous findings and help to quantify <strong>the</strong>relationships. Controlling for provincial differences, higher income per capita issignificantly associated with higher intermediation rates, measured by ei<strong>the</strong>r performingloans or total loans divided by income. This positive association is greater in 1997 thanin 1994. A one percent increase in income increased <strong>the</strong> effective intermediation rate by0.15 percent in 1994 and 0.21 percent in 1997. However, dropping provincial controls,<strong>the</strong> relationships are no longer statistically significant.23

We also examine <strong>the</strong> components of intermediation rates. The effect of incomedifferences on loan performance increases from 1994 to 1997. With provincial controls,a one percent increase in income per capita reduces <strong>the</strong> share of non-performing loans by0.08 percent in 1994 and by 0.21 percent in 1997. When we drop controls for provincialdifferences, we find roughly similar results. Second, <strong>the</strong>re is a consistent negativerelationship between income level and <strong>the</strong> loan-deposit ratio, but this shows upsignificantly only in <strong>the</strong> specification without provincial controls, suggesting that <strong>the</strong>sedifferences are due in part to differences in provincial characteristics o<strong>the</strong>r than averageincome (e.g., quality of alternative investment projects, financial regulation). Fourth,higher income per capita is associated with a more than proportionate increase in depositsper capita, with a one percent increase in income per capita associated with depositincreases of 1.35 percent in 1994 and 1.79 percent in 1997. Without provincial controls,<strong>the</strong> effects are smaller but still significant. Finally, we note that <strong>the</strong>re is a shift towardgreater lending to firms in richer townships and move away from household lending, andthis sensitivity to income also increases over time.Comparing <strong>the</strong> results of specifications controlling and not controlling forprovincial differences suggests that <strong>the</strong> inequities associated with income differences areeven greater within provinces than between provinces. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, relative to a richtownship in <strong>the</strong> same province, a poor township is even worse off than relative to anequally rich township in ano<strong>the</strong>r province. This may be because in ano<strong>the</strong>r province(most likely richer) fewer deposits and loans are likely to be made in <strong>the</strong> rural financialinstitution because of greater financial competition and better alternative projects. In <strong>the</strong>same province, rich townships get more deposits and most funds are lent locally, and <strong>the</strong>24

differences are even more stark. Provincial differences appear to be muting <strong>the</strong> measuredresponse of per capita deposits and loans to income, which may be due to greaterfinancial competition in <strong>the</strong>se areas. One plausible explanation is that households incoastal provinces are more likely to deposit funds in o<strong>the</strong>r financial institutions or ino<strong>the</strong>r investment vehicles.5. Bank governance and loan performanceThe high and increasing percentage of non-performing loans is an essentialcomponent of <strong>the</strong> intermediation failure we have described in poorer areas. Theimportant question is: How much of this can be linked to problems in bank governance?In this final section of <strong>the</strong> paper, we examine <strong>the</strong> links between governance structures andnon-performing loans, and changes in governance structures <strong>the</strong>mselves.From <strong>the</strong> branch bank surveys, we capture governance in a variety of waysincluding: loan authorization limits of branch managers; ex-ante bonus incentives ofbranch mangers measured as a percentage of <strong>the</strong> manager’s base wage; <strong>the</strong> percentage ofloans with collateral; government pressure to renegotiate overdue loans; quarterlyreporting requirements of branches; and <strong>the</strong> time required to resolve overdue loan issuesthrough <strong>the</strong> courts. A priori, we associate more powerful income incentives, <strong>the</strong> use ofcollateral, freedom from government intervention, stricter and more frequent reportingrequirements, and <strong>the</strong> ability to take legal action against defaulting borrowers as keyingredients of better governance structures. Managerial autonomy to make loans can alsobe a key component of a bank governance, especially when combined with incomeincentives that penalize bad managers for making bad loans and reward <strong>the</strong>m for25

decisions that increase branch profitability. Unconstrained autonomy however can leadto moral hazard problems that might undermine banking profitability and efficiency. Weexpect better governance, in turn, to translate into a lower percentage of non-performingloans.Simple descriptive statistics on all of <strong>the</strong> governance-related variables aresummarized in Table 9, which breaks <strong>the</strong> data down by income quartiles of <strong>the</strong>townships. We report both levels in 1997 and changes between 1994 and 1997. Themuch larger sample size for <strong>the</strong> former reflects <strong>the</strong> more complete information we havefor 1997. 14In some important respects, poor areas appear to be handicapped by poorerinstitutional practices. The size of loans that can be approved is much lower than in <strong>the</strong>richest areas, collateral requirements and reporting requirements are more lax, andgovernment influence on lending is higher. However, <strong>the</strong>re are o<strong>the</strong>r aspects that favorpoor areas. Bonus incentives are stronger, perhaps reflecting budgetary shortages, and<strong>the</strong> time it takes to complete lawsuits is shorter, perhaps because <strong>the</strong>re are fewer casesbacklogging <strong>the</strong> system given lower levels of economic activity. In general, changes ingovernance variables is occurring more rapidly in richer areas compared to poorer areas,suggesting that reform is lagging in remote areas.Table 10 reports <strong>the</strong> results of OLS regressions analyzing <strong>the</strong> percentage of nonperformingloans in 1997 as a function of bank governance in 1997, and <strong>the</strong> change innon-performing loans between 1994 and 1997 as a function of governance structurespresent in 1994. We recognize <strong>the</strong> multiple endogeneity problems associated withrelating institutional change and economic performance, so treat <strong>the</strong> relationships more as14 Frequent managerial turnover in <strong>the</strong> bank branches handicapped our efforts to obtain information for1994.26

correlations ra<strong>the</strong>r than making causal inferences. Columns 5-8 of Table 10 report <strong>the</strong>results linking non-performing loans in 1997 to bank governance. In each of <strong>the</strong>regressions, we also include township per capita income as an additional control variable.For comparison, column 5 reports <strong>the</strong> results of <strong>the</strong> bivariate regression of nonperformingloans on income. 15The regressions are nicely suggestive of <strong>the</strong> role ofgovernance. We find that <strong>the</strong> percentage of non-performing loans is negatively correlatedwith branch manager bonus incentives, <strong>the</strong> use of collateral, freedom from governmentpressure, and authorization limits (insignificantly), and positively correlated with <strong>the</strong>length of time required to resolve cases legally. The percentage of non-performing loansis also significantly lower in higher income areas. This may be picking up overall higherloan quality, and possibly unobserved dimensions of local governance structures that arecorrelated with incomes.In column 7, we include as an additional explanatory variable <strong>the</strong> interactionbetween loan authorization limits and managerial bonus incentives. As in column 6, <strong>the</strong>individual coefficients on <strong>the</strong>se two variables remain negative, and now are significant at5 percent. The positive coefficient on <strong>the</strong> interaction term, however, suggests that acombination of high authorization limits and powerful incentives contributes to aweakening of <strong>the</strong> quality of <strong>the</strong> loan portfolio. One interpretation for this result is that <strong>the</strong>combination leads to excessive risk-taking on <strong>the</strong> part of branch managers that ultimatelylead to an increase in <strong>the</strong> percentage of non-performing loans. It also suggests <strong>the</strong> needfor higher authorities to properly balance incentives and rights. In column 8 we include asan additional regressor information on quarterly reporting requirements of <strong>the</strong> bank15 The results are robust to including provincial fixed effects, controlling for branch type, and to excluding<strong>the</strong> income variable.27

anches. Note that our sample size drops to 57 because of missing observations. Thesign on <strong>the</strong> variable is as predicted, but <strong>the</strong> coefficient is not measured with muchprecision and is statistically insignificant. The remaining coefficients are similar inmagnitude to those reported in columns 6 and column7.In columns 1-4, we analyze <strong>the</strong> effect of governance structures present in 1994 onchange in non-performing loans between 1994 and 1997. We also include townshipincome in 1994, and in column 4, add <strong>the</strong> level of non-performing loans in 1994. Limitedinformation on governance in 1994 restricts our attention to a much smaller set ofvariables than used above, and to a relatively small sample of RCC and ABC branches.The results are informative however. First, governance seems to matter: The increase innon-performing loans is smaller in townships in which government influence is less,<strong>the</strong>re is more frequent reporting to higher level county branches, and managers have morediscretion in extending new loans. Second, <strong>the</strong> increase is less in townships with higherincomes. Since <strong>the</strong> change in non-performing loans is not correlated with <strong>the</strong> growth inour income measure (result not reported here) over <strong>the</strong> same period, one interpretation forthis result is that <strong>the</strong> income variable is picking up “unobserved” dimensions ofgovernance at <strong>the</strong> township level that are positively correlated with incomes. Third, wefind that <strong>the</strong> increase in non-performing loans over this three-year window is lower inbranches with a higher stock of non-performing loans of 1994. This may reflectadditional actions being taken by <strong>the</strong>se branches to address <strong>the</strong> non-performing loanproblem. Note that <strong>the</strong> inclusion of <strong>the</strong> stock of non-performing loans in <strong>the</strong> regressiondoes not significantly affect <strong>the</strong> remaining coefficients.28

In Table 11 , we examine changes in governance levels between 1994 and1997. We keep <strong>the</strong> regressions simple and examine <strong>the</strong> effect of incomes in 1994, <strong>the</strong>level of governance in 1994, and <strong>the</strong> stock of non-performing loans in 1994 on <strong>the</strong>changes in governance between 1994 and 1997. Three key questions motivate thisexercise: first, are <strong>the</strong> changes in governance greatest where <strong>the</strong>y are most needed, i.e.branches with <strong>the</strong> highest stock of non-performing loans; second, are governancestructures converging across localities; and third, are poorer areas lagging behind in <strong>the</strong>pace of reform, all else held constant?In general, it appears that <strong>the</strong>re is some convergence going on as suggested by <strong>the</strong>negative coefficients on <strong>the</strong> governance variables in 1994. The overall trend appears to betoward better governance, with <strong>the</strong> greatest changes occurring in those areas with lowermeasures of governance in 1994. 16For three of <strong>the</strong> five governance variables (loanauthorization, incentives, and reporting requirements), it is also <strong>the</strong> case that <strong>the</strong>improvement in governance is positively related (but not statistically significant) to <strong>the</strong>stock of non-performing loans in 1994. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, <strong>the</strong> changes are greatest where<strong>the</strong>y are probably most needed. However, government pressure on branches appears tobe increasing in areas with a higher stock of non-performing loans. The likely reason forthis correlation is that it reflects government efforts to obtain relief for firms under <strong>the</strong>iradministration. Contrary to our expectation, we also find that <strong>the</strong> increase in <strong>the</strong> use ofcollateral appears to be lower in areas with a higher stock of non-performing loans.Finally, it also appears that with <strong>the</strong> exception of bonus incentives, <strong>the</strong> changes ingovernance are occurring most rapidly in higher income areas.16 This result should be interpreted carefully, however, because a regression of a change in a variable on itslagged value automatically imparts a negative bias. A number of <strong>the</strong> variables are also truncated.Unfortunately, <strong>the</strong>re is not much we can do to correct <strong>the</strong>se problems.29

What are <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> implications of our analysis for poorer areas? Several thingsbode well. First, localities with higher stocks of non-performing loans appear to beslightly more aggressive in carrying out reform. Since it is poorer regions that have <strong>the</strong>highest stock of non-performing loans, this suggests that governance reform in <strong>the</strong>seregions may be responsive to <strong>the</strong> pressures of non-performing loans. Second, <strong>the</strong>increase in non-performing loans is smaller <strong>the</strong> higher <strong>the</strong> stock of bad loans in 1994.This may be picking up some of <strong>the</strong> benefits of <strong>the</strong> improvement in governmentstructures reported above. Yet possibly counteracting some of <strong>the</strong>se trends is <strong>the</strong>tendency for changes in governance to be greatest in localities with <strong>the</strong> highest incomes.Despite better overall governance in <strong>the</strong>se regions, <strong>the</strong> need for governance reformremains high.6. ConclusionsWe summarize some of <strong>the</strong> main findings from <strong>the</strong>se simple empirical exercises:1. The ratio of loans to income, a measure of financial intermediation, was stable in richareas but fell in poor areas. The ratio of performing loans to income, a better measure ofeffective intermediation, fell in all areas, but much more rapidly in poor areas.2. Non-performing loans are significant in all areas, but greater in poor areas. They haveincreased over time in all regions, but faster in <strong>the</strong> richest and poorest areas. While <strong>the</strong>share of household loans that are non-performing has remained high but relatively stable,<strong>the</strong> share of TVE loans that are non-performing has increased rapidly to exceed that ofhousehold loans.3. Loan-deposit ratios, measures of net fund outflow, are lower in rural financialinstitutions than in all banks and lower in poor areas than in rich areas. They havedeclined over time at a rate similar to that of all banks, but have declined more in richerareas.4. Income per capita grew faster in poor areas relative to rich areas, but deposits grewslower.30

5. <strong>Financial</strong> institutions in poor areas showed a greater willingness to lend to householdsand this relative trend streng<strong>the</strong>ned over time.6. The non-performing loans problem is closely tied to institutional practices, or bankgovernance. While banks with greater repayment problems are reforming faster allthings equal, it is still <strong>the</strong> case <strong>the</strong> richer areas tend to have better governance and to bereforming faster.If we consider <strong>the</strong> motivating question for <strong>the</strong> paper and its title, <strong>the</strong> most accurateanswer is affirmative, but not for <strong>the</strong> anticipated reason, i.e., greater fund flows out ofpoor areas. While <strong>the</strong> increase in non-performing loans is undermining financialintermediation throughout rural China, <strong>the</strong> problem is worse in poor areas because ofslower deposit growth and more serious repayment problems. However, <strong>the</strong> way <strong>the</strong>motivating question is posed may be misleading because <strong>the</strong>se changes are not so much<strong>the</strong> result of financial reform as <strong>the</strong> inability of reform to reduce non-performing loanseven as many regulations (especially interest controls and restrictions on interbanklending) continue to constrain <strong>the</strong> decisions of bank managers and link lending volumeclosely to local resources (deposits). If this, in fact, is what is happening, or ra<strong>the</strong>r nothappening, <strong>the</strong>re is still ample scope for new changes and new distributionalconsequences as China continues to liberalize <strong>the</strong> financial sector in anticipation of WTOentry.To draw policy implications, it is important to understand <strong>the</strong> reasons for poorloan performance, especially in poor areas. If poor performance reflects <strong>the</strong> lack of goodprojects, <strong>the</strong> efficiency-equity tradeoff becomes quite stark, and policy-makers might bebest advised to improve <strong>the</strong> economic environment to make investments more desirable.However, if poor performance reflects institutional failings of financial institutions inremote areas, ei<strong>the</strong>r because of stifling regulation or poor management, <strong>the</strong>re may be31

greater scope for reforms that can advance both equity and efficiency goals. While manyidentification problems make our empirical results more suggestive than definitive, we dofind evidence that both <strong>the</strong> quality of projects and institutional practices matter. Some of<strong>the</strong> trends in <strong>the</strong> speed of institutional reforms are encouraging, o<strong>the</strong>rs disquieting. But<strong>the</strong> evidence suggests <strong>the</strong>re may be scope improved performance with possibly beneficialdistributional consequences from continued reforms.Experience in o<strong>the</strong>r countries suggests that <strong>the</strong> poor are capable of saving at highrates and that <strong>the</strong>y are both credit-worthy and have demand for loans (Morduch, 1999).But savings responds most to convenience and security, while lending to <strong>the</strong> poor cannotbe profitable unless interest rates are allowed to be higher than in o<strong>the</strong>r areas (tocompensate for <strong>the</strong> higher administrative costs). The early experience of microfinanceinstitutions operating in China’s poor areas has been very positive, supporting <strong>the</strong> notionthat institutional reform and greater regulatory flexibility may encourage financialinstitutions to lend successfully in poor areas (Park and Ren, 2001).Thus, prognosis for <strong>the</strong> future depends very much upon reforms that have yet tooccur in China. If inter-bank markets are liberalized without interest rate liberalization,<strong>the</strong> effects could be quite negative for poor areas, but more open entry and pricingpolicies could be quite helpful. Underlying institutional development to better enforcecontracts, share credit histories, increase <strong>the</strong> effectiveness of collateral and guarantors assecurity for loans, increase <strong>the</strong> quality of managers and loan officers, and provideappropriate incentives will support more effective financial intermediation in both richareas and poor, but <strong>the</strong>ir importance to lending in poor areas may be even greater becauseof <strong>the</strong> greater institutional challenges to banking with <strong>the</strong> poor.32

ReferencesBesley, Timothy. 1994. “How do Market Failures Justify Interventions in Rural CreditMarkets?” The World Bank Research Observer 9(1): 27-47.Brandt, Loren, and Xiaodong Zhu. 2000. “Redistribution in a Decentralized Economy:Growth and Inflation in Refor China,” Journal of Political Economy 108(2): 422-439.Brandt, Loren, and Xiaodong Zhu. 2001. From Intermediation by Diversion toDisintermediation in China, University of Toronto, mimeo,China <strong>Financial</strong> Yearbook 1999 (Beijing: China <strong>Financial</strong> Press).China Statistical Yearbook 1998 (Beijing: China Statistics Press).China Statistical Yearbook 1999 (Beijing: China Statistics Press).China Statistical Yearbook 2000 (Beijing: China Statistics Press).Gertler, Mark, and Andrew Rose. 1996. “Finance, Public Policy, and Growth,” inGerard Capri, Jr., Izak Atiyas, and James Hanson, eds., <strong>Financial</strong> Reform: Theory andExperience (New York: St. Martin’s Press), pp. 115-128.King, Robert, and Levine, Ross. 1993. “Finance and Growth: Schumpeter Might BeRight.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 108, 3:713-37.Kraay, Aart. 2000. “Household Saving in China,” TheWorld Bank Economic Review14(3): 545-570.Lardy, Nicholas. 1998. China’s Unfinished Economic Revolution (Washington, D.C.:Brookings Institution Press).Levine, Ross. 1997. “<strong>Financial</strong> Development and Economic Growth: Views andAgenda.” Journal of Economic Literature 35, 2:688-726.Levine, Ross, and Zervos, Sara. 1998. “Stock Markets, Banks, and Economic Growth.”American Economic Review 88, 3:537-58.Lipton, Michael. 1984. “Urban Bias Revisited,” Journal of Development Studies 20(3):139-66.McKinnon, Ronald. 1994. “Gradual versus Rapid Liberalization in Socialist Economies:The Prble of Macroeconoic Control,” Proceedings of <strong>the</strong> World Bank Annual Conferenceon Development Economics 1993 (Washington, D.C.: The World Bank), pp.63-94.34

Naughton, Barry. 1995. Growing Out of <strong>the</strong> Plan: Chinese Economic Reform, 1978-92(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).Nyberg, Al, and Scott Rozelle. 1999. Accelerating China’s Rural Transformation(Washington, D.C.: The World Bank).Park, Albert, Loren Brandt, and John Giles. 1997. Giving Credit Where Credit is Due:The Changing Role of Rural <strong>Financial</strong> Institutions in China, William Davidson InstituteWorking Paper No. 71.Park, Albert, and Minggao Shen. 2000. Joint Liability Lending and <strong>the</strong> Rise and Fall ofChina’s Township and Village Enterprises, mimeo.Park, Albert, and Changqing Ren. 2001. “Microfinance with Chinese Characteristics,”World Development 29(1): 39-62.Park, Albert, and Scott Rozelle. 1998. “Reforming State-Market Relations in RuralChina,” Economics of Transition 6(2): 461-480.Park, Albert, and Kaja Sehrt. Forthcoming. “Tests of <strong>Financial</strong> Intermediation andBanking Reform in China,” Journal of Comparative Economics.Park, Albert, and Sangui Wang. Will Credit Access Help <strong>the</strong> <strong>Poor</strong>?: Evidence fromChina, mimeo.Putterman, Louis. 1992. “Dualism and Reform in China,” Economic Development andCultural Change 40(3): 467-493.Rajan, Raghuram, and Zingales, Luigi. 1998. “<strong>Financial</strong> Dependence and Growth.”American Economic Review 88, 3:559-86.Sehrt, Kaja. 1999. Banks Versus Budgets: China’s <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Reforms</strong> 1978-1996, Ph.D.dissertation, Department of Political Science, University of Michigan.Shen, Minggao, and Albert Park. 2001. Decentralization in <strong>Financial</strong> Institutions:Theory and Evidence from China, mimeo.Wong, Christine, Christopher Heady, and Wing Woo. 1995. Fiscal Management andEconomic Reform in <strong>the</strong> People’s Republic of China (Hong Kong: Oxford UniversityPress).35

Table 1Rural <strong>Financial</strong> Institution Balance Sheet Summary Statistics, 1994 and 19971994 1997N Assets Dep./ Loans/ Of Assets Dep./ Loans/ Of(millionyuan)Assets Assets which:firms(millionyuan)Assets Assets which:firmsFull sample 143 47 0.58 0.42 0.74 82 0.64 0.41 0.71ProvincesZhejiang 39 76 0.49 0.37 0.73 145 0.58 0.39 0.71Jiangsu 45 21 0.70 0.49 0.82 55 0.67 0.38 0.83Sichuan* 23 20 0.73 0.51 0.74 33 0.79 0.52 0.70Shanxi* 36 14 0.81 0.54 0.57 21 0.88 0.60 0.52Income quartilesI 31 95 0.53 0.38 0.81 172 0.58 0.37 0.75II 32 48 0.51 0.39 0.66 94 0.57 0.37 0.66III 34 31 0.71 0.51 0.83 44 0.83 0.58 0.78IV 33 12 0.83 0.46 0.37 18 0.95 0.53 0.35Bank typeABC 52 62 0.39 0.30 0.57 117 0.45 0.31 0.61RCC 91 38 0.76 0.53 0.83 62 0.84 0.52 0.77Note: All means are weighted by <strong>the</strong> amount of funds.*In 1998, <strong>the</strong> share of funds from deposits was 0.87 in Sichuan and 0.92 in Shanxi.*In 1998, collective firms, private firms, and o<strong>the</strong>rs accounted for loan shares of 0.69, 0.02, and 0.28 in Sichuan and 0.47, 0.07, and0.46 in Shanxi.36

Table 2<strong>Financial</strong> Intermediation Indicators, 1994 and 19971994 1997 Annual %change1994-97N Loans/Inc.Perf./Inc.Loans/Inc.Perf./Inc.Loans/Inc.Perf./Inc.Full sample 127 0.38 0.31 0.38 0.28 0.01 -0.04ProvincesZhejiang 30 0.49 0.43 0.50 0.40 0.00 -0.03Jiangsu 45 0.27 0.21 0.26 0.19 0.01 -0.04Sichuan* 21 0.31 0.24 0.28 0.19 0.01 -0.02Shanxi* 31 0.60 0.43 0.56 0.35 0.00 -0.08IncomequartilesI 31 0.41 0.36 0.45 0.34 0.04 -0.01II 34 0.31 0.25 0.31 0.26 -0.01 -0.02III 31 0.40 0.31 0.35 0.24 -0.03 -0.09IV 31 0.43 0.30 0.40 0.23 -0.02 -0.13Bank typeABC 48 0.35 0.29 0.40 0.31 0.05 0.01RCC 79 0.40 0.33 0.37 0.27 -0.02 -0.07Note: All values are in 1994 yuan, deflated by using provincial consumer price indices.Means for per capita variables are weighted by township population. Means forloans/income and performing loans/income are weighted by total income (income percapita x population).*In 1998, loans p.c., performing loans p.c., and deposits p.c. were 467, 339, and 870 yuanfor Sichuan, and 731, 387, and 1153 yuan for Shanxi. The ratio of loans p.c. to incomep.c. and <strong>the</strong> ratio of performing loans p.c. to income p.c. was 0.27 and 0.19 for Sichuanand 0.50 and 0.27 for Shanxi.37

Table 3Share of Outstanding Loans that are Non-performing, 1994 and 19971994 1997 AnnualN OVER INACT DEAD Total OVER INACT DEAD Total %∆Full sample 145 0.09 0.07 0.01 0.17 0.13 0.08 0.02 0.24 0.15ProvincesZhejiang 39 0.08 0.03 0.01 0.12 0.13 0.06 0.01 0.20 0.18Jiangsu 47 0.07 0.12 0.03 0.21 0.09 0.10 0.05 0.25 0.12Sichuan* 23 0.16 0.08 0.00 0.25 0.19 0.10 0.03 0.32 0.07Shanxi* 36 0.16 0.12 0.03 0.30 0.21 0.15 0.04 0.40 0.14IncomequartilesI 31 0.06 0.05 0.01 0.13 0.15 0.08 0.02 0.25 0.32II 34 0.11 0.07 0.01 0.19 0.08 0.06 0.03 0.16 -0.07III 34 0.14 0.09 0.02 0.25 0.16 0.12 0.05 0.32 0.08IV 33 0.15 0.11 0.05 0.32 0.23 0.18 0.03 0.44 0.14Bank typeABC 53 0.08 0.09 0.01 0.17 0.08 0.09 0.03 0.20 0.00RCC 92 0.10 0.06 0.02 0.17 0.17 0.08 0.02 0.26 0.23Borrowertype**:TVEs 36 0.15 0.06 0.02 0.23 0.15 0.21 0.03 0.38Households 51 0.18 0.13 0.01 0.32 0.15 0.15 0.03 0.33Note: All means are weighted by <strong>the</strong> amount of outstanding loans.Definitions: OVER=overdue loans, INACT=inactive loans (overdue more than 2 years),DEAD=loans with no expectation of repayment because of <strong>the</strong> following reasons: a) <strong>the</strong>borrower has died or cannot be located; b) <strong>the</strong> borrower has gone bankrupt; or c) <strong>the</strong> loanis more than three years overdue.*In 1998, Sichuan and Shanxi overdue loans were 0.28 and 0.48 of outstanding loans.**For Sichuan and Shanxi only.38

Table 4Loan-Deposit Ratios, 1994 and 19971994 1997 Annual %∆N AllLoansPerf.LoansAllLoansPerf.LoansAllLoansPerf.LoansFull sample 142 0.71 0.59 0.64 0.48 -0.07 -0.03ProvincesZhejiang 38 0.73 0.64 0.67 0.54 -0.08 -0.04Jiangsu 45 0.70 0.55 0.56 0.42 -0.09 -0.06Sichuan* 23 0.70 0.53 0.66 0.45 -0.04 -0.05Shanxi* 36 0.66 0.46 0.69 0.41 -0.02 0.00Income quartilesI 31 0.71 0.61 0.63 0.47 -0.11 -0.05II 32 0.77 0.63 0.66 0.55 -0.05 -0.04III 34 0.71 0.53 0.70 0.48 -0.02 0.01IV 33 0.55 0.38 0.57 0.32 -0.05 0.05Bank typeABC 51 0.75 0.61 0.66 0.53 -0.06 -0.03RCC 91 0.70 0.57 0.62 0.46 -0.08 -0.03Note: All loan values are divided by total deposits. Mean loan-deposit ratios areweighted by <strong>the</strong> amount of deposits.*In 1998, Sichuan and Shanxi, loan-deposit ratios were 0.57 and 0.63, of whichperforming loans were 0.41 and 0.33.Table 5Loan-Deposit Ratios from O<strong>the</strong>r Surveys of RFIs, 1988, 1994-1996N 1988 1994 1995 19961996 National Village Survey 80 0.94 0.68 0.731997 China Rural Poverty Survey 19 0.73 0.61 0.55 0.54Note: All means are weighted by <strong>the</strong> amount of deposits.39

Table 6Deposits and Income Per Capita, 1994 to 1997NDep.p.c1994 1997 Annual %∆Income Dep. Income Dep.p.c. p.c p.c. p.cIncomep.c.Full sample 125 1002 1860 1487 2515 0.12 0.11ProvincesZhejiang 30 1572 2357 2377 3301 0.12 0.11Jiangsu 43 816 2160 1309 2844 0.14 0.11Sichuan* 21 593 1242 741 1612 0.10 0.09Shanxi* 31 785 871 998 1202 0.08 0.11Income quartilesI 31 1853 3169 2801 3910 0.13 0.07II 32 772 1876 1304 2709 0.15 0.12III 31 718 1308 901 1844 0.09 0.11IV 31 590 748 771 1111 0.08 0.13Bank typeABC 47 889 1882 1488 2526 0.15 0.11RCC 78 1076 1846 1485 2508 0.10 0.10Note: All values are converted to 1994 yuan using provincial CPIs. Means for depositand loan growth rates are weighted by base year starting values. Mean income p.c.growth is weighted by 1994 township population.40

Table 7Decomposition of Changes in <strong>Financial</strong> Intermediation(annual growth rates, 1994 to 1997)Perf.loans/incomeAllloans/incomePerf.loanshareLoans/depN PL/Y L/Y PL/L L/D D/POP Y/POPFull sample 125 -0.04 0.01 -0.04 -0.03 0.12 0.11ProvincesZhejiang 30 -0.03 0.00 -0.05 -0.03 0.12 0.11Jiangsu 43 -0.04 0.01 -0.03 -0.06 0.14 0.11Sichuan* 21 -0.02 0.01 -0.04 0.00 0.10 0.09Shanxi* 31 -0.08 0.00 -0.07 0.05 0.08 0.11Income quartilesI 31 -0.01 0.04 -0.06 -0.05 0.13 0.07II 32 -0.01 -0.01 -0.01 -0.04 0.15 0.12III 31 -0.09 -0.03 -0.04 0.01 0.09 0.11IV 31 -0.13 -0.02 -0.10 0.05 0.08 0.13Bank typeABC 47 0.01 0.05 -0.03 -0.02 0.15 0.11RCC 78 -0.07 -0.02 -0.05 -0.03 0.10 0.10Dep.p.c.Inc.p.c.Table 8<strong>Financial</strong> Performance and Level of Economic DevelopmentEstimates from OLS Regressions of Performance Indicators on Income Per CapitaDependent variableWith controls forprovincialdifferences(1)No controls forprovincial differences(2)N 1994 1997 1994 1997126 **0.15 ***0.21 0.01 0.03Performing loans per capita/income per capitaLoans per capita/income per 127 *0.14 ***0.24 -0.05 -0.03capitaNonperforming loans/total loans 131 **-0.08 ***-0.21 ***-0.14 ***-0.20Loans/deposits 129 -0.32 -0.52 *-0.41 **-0.42Deposits per capita (1994 yuan) 125 ***1.35 ***1.79 ***0.91 ***1.03Loans to firms/total loans 118 ***0.28 ***0.41 ***0.33 ***0.38Loans to households/total loans 156 ***-0.16 ***-0.28 ***-0.30 ***-.40Note: Independent variable is log of income per capita (in 1994 yuan).*10 percent significance level, **5 percent, ***1 percentSpecification (1) includes province-bank type interaction dummy variables.41

Specification (2) includes dummy variable for bank type only.42

Table 9Governance by Income QuartilesGovernance in 1997 Change in Governance, 1994-1997Income QuartilesIncome QuartilesVariable I II III IV I II III IVLoan9.64 0.83 1.82 0.93 5.00 0.31 -0.83 -1.21AuthorizationBonus Incentive 0.56 0.48 0.47 0.63 * * -.09 0.34Collateral 49.6 53.1 62.3 38.7 33.2 31.1 16.1 7.2Gov’t Pressure 3.71 3.58 3.88 3.45 1.2 1.1 1.5 0.28Rep. Require. 0 -.6 -.1 0Time to End 4.71 4.35 5.49 1.98 * * * *Lawsuit (months)Number of Obs 14 24 26 20Notes: Loan authorization limits are reported in 10,000 RMB. Bonus incentives measure <strong>the</strong> exantebonus in event of target fulfillment as a percentage of <strong>the</strong> base wage. Collateral is <strong>the</strong>percentage of loans to TVEs secured with collateral. Government pressure is measured on adecreasing scale from 1-6.Table 10Governance and Non-Performing Loans in Township BranchesChange in Non-Performing LoansNon-PerformingLoans in 1997Income, 1994 -0.102(-2.70)-0.128(-3.28)-0.127(-3.76)-0.120(-4.92)Income 1997 -0.102(-5.05-0.111(-5.82)-0.110(-5.66)-0.105(-4.55)Loan Authorization,1994-0.001(-0.21)-0.008(-1.49)-0.014(-2.39)Loan Authorization,1997-0.001(-0.41)-0.016(-1.78)-0.012(-2.24)Bonus Incentive,1997-0.080(-1.46)-0.112(-2.02)-0.063(-0.98)Authorization*Bonus 0.041(1.85)Loans w/ Collateral,1997-0.002(-2.70)-0.002(-2.57)-0.002(-2.16)Gov’t Intervention,1994-0.024(-1.54)-0.044(-2.96)-0.040(-2.85)Gov’t Intervention,1997-0.029(-2.01)-0.032(-2.16)-0.022(-1.37)Rep. Requirements,1994-0.077(-2.77)-0.090(-3.27)Rep. Requirements,1997-0.051(-0.89)Time to End Lawsuit 0.010(2.69)0.010(2.97)0.010(3.20)Non-PerformingLoans, 1994-0.485(-3.06)Number of Obs. 59 59 46 46 84 84 5743

R 2 0.10 0.14 0.31 0.49 0.39 0.41 0.41 0.4044

Table 11Changes in Governance between 1994 and 1997Loan Authorization Bonus Collateral Gov’t Pressure Rep. RequirementsIncome, 1994 1.633(1.62)2.300(1.81-1.014(-2.57)-1.062(-3.0210.79(2.58)5.12(1.130.389(2.45)0.106(0.840.028(1.54)0.074(1.7)Loan Authorization, 1994 -0.714(-7.06Bonus, 1994 -0.488(-1.82)Loans w/ Collateral, 1994 -0.377(-3.71Gov’t Pressure, 1994 -0.349(-4.49)Rep. Requirements, 1994 -0.363(-2.80)Non-perf. Loans in 1994 2.33(1.47)0.844(1.65)-25.94(-1.01)-1.05(-1.47)0.276(1.36)Number of observationsR 2 73 69 25 25 47 45 92 84 94 800.11 0.52 0.26 0.48 0.10 0.30 0.06 0.27 0.01 0.3145

Appendix Table 1Loan Composition, Sichuan and Shaanxi, 1994 and 19981994 1998N Firms HH Ag O<strong>the</strong>r Firms HH Ag O<strong>the</strong>rFull sample 59 0.32 0.15 0.22 0.31 0.38 0.20 0.16 0.26ProvincesSichuan 23 0.48 0.09 0.19 0.24 0.50 0.18 0.16 0.17Shanxi 36 0.19 0.20 0.25 0.36 0.24 0.27 0.11 0.38Income quartilesI 13 0.42 0.08 0.22 0.28 0.52 0.09 0.07 0.32II 14 0.33 0.04 0.36 0.27 0.29 0.16 0.29 0.27III 15 0.19 0.29 0.12 0.40 0.22 0.38 0.07 0.32IV 14 0.05 0.51 0.09 0.35 0.11 0.68 0.02 0.19Bank typeABC 16 0.13 0.15 0.22 0.51 0.11 0.20 0.12 0.57RCC 43 0.45 0.15 0.22 0.18 0.48 0.24 0.14 0.15Note: All means are weighted by <strong>the</strong> amount of outstanding loans.46