Self-help Groups as Financial Intermediaries in India ... - Sa-Dhan

Self-help Groups as Financial Intermediaries in India ... - Sa-Dhan

Self-help Groups as Financial Intermediaries in India ... - Sa-Dhan

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

List of AcronymsAIAMEDAIMSAPMASASAASCAASSEFACAPARTCASHECBOCBsCCACDFCLACREDITCYSDDPIPDRDADWCRAFWWBGTZGVHCSSCHDFCHUDCOICCOICDSIFADIGAJLGLEADMACSMACTSMBTM-CRILMFMFIMISNABARDNBFCAll <strong>India</strong> Association for Micro Enterprise DevelopmentAssess<strong>in</strong>g the Impact of Microenterprise ServicesAndhra Pradesh Mahila Abhivruddhi SocietyActivists for Social AlternativesAccumulat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Sa</strong>v<strong>in</strong>gs and Credit AssociationAssociation of <strong>Sa</strong>rva Seva FarmsCouncil for Advancement and Promotion of Agriculture and RuralTechnologyCredit and <strong>Sa</strong>v<strong>in</strong>g for Household EnterpriseCommunity-b<strong>as</strong>ed OrganisationCommercial BanksConvergent Community ActionCooperative Development FoundationCluster-level AssociationCredit Rotation for Empowerment and Development through InstitutionBuild<strong>in</strong>g and Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gCentre for Youth and Social DevelopmentDistrict Poverty Initiatives ProjectDistrict Rural Development AgencyDevelopment of Women and Children <strong>in</strong> Rural Are<strong>as</strong>Friends of Women’s World Bank<strong>in</strong>gGesellschaft fur Technische ZusammenarbeitGram VidiyalHoly Cross Social Service CentreHous<strong>in</strong>g Development F<strong>in</strong>ance CorporationHous<strong>in</strong>g and Urban Development Corporation Ltd.Interchurch organization for development cooperationIntegrated Child Development SchemeInternational Fund for Agricultural DevelopmentIncome Generation ActivitiesJo<strong>in</strong>t Liability GroupLeague for Education and DevelopmentMutually Aided Cooperative SocietyMutually Aided Cooperative Thrift SocietyMutual Benefit TrustMicro-Credit Rat<strong>in</strong>gs & Guarantees <strong>India</strong> Ltd.Microf<strong>in</strong>anceMicrof<strong>in</strong>ance InstitutionManagement Information SystemNational Bank for Agriculture and Rural DevelopmentNon-Bank<strong>in</strong>g F<strong>in</strong>ance Companyiv

NBJKNGONOFPLAPRAPRADANRBIRGVNRMKROCROSCARRBsSAPAPSEWASGSYSHARESHGSHPISIDBISJSKSMBTSNFTNWDCUNDPUNICEFNav Bharat Jagriti KendraNon Government OrganisationNet Owned FundParticipatory Learn<strong>in</strong>g and ActionParticipatory Rural AppraisalProfessional Assistance for Development ActionReserve Bank of <strong>India</strong>R<strong>as</strong>htriya Grameen Vik<strong>as</strong> NidhiR<strong>as</strong>htriya Mahila KoshRegistrar of CooperativesRotat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Sa</strong>v<strong>in</strong>gs and Credit AssociationRegional Rural BanksSouth Asia Poverty Alleviation Project<strong>Self</strong> Employed Women's AssociationSwarnajayanti Gram Swarozgar YojanaSociety for Help<strong>in</strong>g Awaken<strong>in</strong>g of Rural Poor through Education<strong>Self</strong> Help Group<strong>Self</strong>-Help Promot<strong>in</strong>g InstitutionSmall Industries Development Bank of <strong>India</strong><strong>Sa</strong>rva Jana Seva Kosh<strong>Sa</strong>rvodaya Mutual Benefit Trust<strong>Sa</strong>rvodaya Nano F<strong>in</strong>anceTamil Nadu Women’s Development CorporationUnited Nations Development ProgrammeUnited Nations Children’s Fundv

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY1. Introduction1.1 This study, which h<strong>as</strong> been undertaken for <strong>Sa</strong>-<strong>Dhan</strong>, New Delhi on behalf of ICCOand Cordaid, supplements studies undertaken by I/C Consult on the self-<strong>help</strong> group(SHG) landscape <strong>in</strong> <strong>India</strong> (Bosch, 2001; & Bosch and Damen, 2000). It analyses therole and development of SHGs <strong>in</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>in</strong>termediation <strong>in</strong> rural <strong>India</strong>.1.2 The pr<strong>in</strong>cipal objective of the study is to contribute to a consistent and relevantfund<strong>in</strong>g policy for ICCO and Cordaid. It seeks to achieve an understand<strong>in</strong>g of “bestpractice” <strong>in</strong> SHG development <strong>in</strong> <strong>India</strong> and to <strong>help</strong> direct donor funds formicrof<strong>in</strong>ance (MF).1.3 The study addresses three ma<strong>in</strong> issues:• Efficiency: What can be said about the average cost of SHG promotion both with andwithout emph<strong>as</strong>is on social and political empowerment? What difference does thecredit plus approach make to average SHG promotion costs?• Effectiveness: What is known through results of <strong>as</strong>sessment studies of the effects andimpact of SHG promotion? What is known about the results of monitor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dicatorsof impact?• Susta<strong>in</strong>ability: What k<strong>in</strong>d of susta<strong>in</strong>ability or ph<strong>as</strong>e out strategy is employed byNGOs?1.4. The study is b<strong>as</strong>ed on a review of literature on SHGs, the experiences of sevenlead<strong>in</strong>g NGOs <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> the formation of SHGs and <strong>in</strong>terviews with chief executivesand staff of a dozen other major NGOs/ projects promot<strong>in</strong>g SHGs.2. SHG Development <strong>in</strong> <strong>India</strong>: An Overview2.1 While the term ‘self-<strong>help</strong> group’ or SHG can be used to describe a wide range off<strong>in</strong>ancial and non-f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>as</strong>sociations, <strong>in</strong> <strong>India</strong> it h<strong>as</strong> come to refer to a form ofAccumulat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Sa</strong>v<strong>in</strong>g and Credit Association (ASCA) promoted by government agencies,NGOs or banks. These groups manage and lend their accumulated sav<strong>in</strong>gs and externallyleveraged funds to their members.2.2 SHGs have varied orig<strong>in</strong>s, mostly <strong>as</strong> part of <strong>in</strong>tegrated development programmes runby NGOs with donor support. The major programme <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>in</strong>termediationby SHGs is the SHG-bank L<strong>in</strong>kage Programme. This Programme w<strong>as</strong> launched <strong>in</strong> 1992by National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD), the apex bank forrural development <strong>in</strong> <strong>India</strong>. By March 2002, the programme covered 7.8 million familieswith 90 per cent women members. On-time repayment of loans w<strong>as</strong> over 95% for banksparticipat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the programme. It also <strong>in</strong>volved 2,155 non-government organizationsvi

(NGOs) and other self-<strong>help</strong> promot<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>stitutions. NABARD’s corporate mission is tomake available microf<strong>in</strong>ance services to 20 million poor households, or one-third of thepoor <strong>in</strong> the country, by 2008. However, there is at present a high degree of concentration<strong>in</strong> the southern states, with just two states, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu account<strong>in</strong>gfor more than 66% of the SHGs l<strong>in</strong>ked to banks.2.3 The outreach of SHG-bank l<strong>in</strong>kage may seem impressive, but <strong>in</strong> the context of themagnitude of poverty <strong>in</strong> <strong>India</strong> and the flow of funds for poverty alleviation, it represents avery small <strong>in</strong>tervention. Only about one-third of the SHG members are able to accessloans out of external funds <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>itial years. Thus of 4.5 million families covered byMarch 2001, only 1.5 million would have received a loan of an average of Rs. 3,000 atpresent. Disbursements under the poverty-focused self-employment programme SwarnaJayanti Swarozgar Yojana (SGSY), meant for families below the poverty l<strong>in</strong>e, were Rs.642.34 crores * dur<strong>in</strong>g 2000-2001, <strong>as</strong> aga<strong>in</strong>st Rs. 250.62 crores under bank l<strong>in</strong>kage.2.4 Apart from NABARD, about half a dozen other apex bodies or wholesalers provideloans to f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>in</strong>termediaries for on-lend<strong>in</strong>g to SHGs. These <strong>in</strong>clude the SmallIndustries Development Bank of <strong>India</strong> (SIDBI), R<strong>as</strong>htriya Mahila Kosh (RMK), Hous<strong>in</strong>gand Urban Development Corporation (HUDCO), Hous<strong>in</strong>g Development F<strong>in</strong>anceCorporation (HDFC) and Friends of Women’s World Bank<strong>in</strong>g (FWWB). Donors andbanks, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Rabobank, also provide grants and loans to microf<strong>in</strong>ance <strong>in</strong>stitutions(MFIs) for on-lend<strong>in</strong>g to SHGs and federations of SHGs.2.5 The lead<strong>in</strong>g SHG-promot<strong>in</strong>g NGOs constitute a mixed group that <strong>in</strong>cludes both pureSHG promoters <strong>as</strong> well <strong>as</strong> NGOs operat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>as</strong> MFIs. They have developed a variety of<strong>in</strong>stitutional arrangements, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g cooperatives, to provide access to f<strong>in</strong>ancial servicesto the poor, particularly women.3. Paths of SHG Development: NGO Strategies and Structures for <strong>F<strong>in</strong>ancial</strong>Intermediation3.1 L<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g SHGs directly to banks is the b<strong>as</strong>ic model <strong>in</strong> which an SHG, promoted by anNGO or other <strong>in</strong>stitution, can access a multiple of its sav<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> the form of loan funds ora c<strong>as</strong>h credit limit from the local rural bank. The SHG onlends the funds it accesses frombanks to its members. The bank l<strong>in</strong>kage model a sav<strong>in</strong>gs-led model, with a m<strong>in</strong>imumsav<strong>in</strong>gs period of 6 months prior to the availability of bank credit. The quantum of creditavailable to SHGs starts from parity with sav<strong>in</strong>gs and can <strong>in</strong>cre<strong>as</strong>e to eight times the levelof SHG sav<strong>in</strong>gs.3.2 The SHG-bank l<strong>in</strong>kage model provides the cheapest and most direct source of funds.However, this h<strong>as</strong> to be set aga<strong>in</strong>st the low volume of funds that available through thischannel <strong>in</strong> view of the l<strong>in</strong>kage of credit with SHG sav<strong>in</strong>gs. Further, the SHG is notnecessarily the appropriate unit for organis<strong>in</strong>g a host of other community-b<strong>as</strong>ed f<strong>in</strong>ancialand non-f<strong>in</strong>ancial services. Many lead<strong>in</strong>g NGOs have formed federations of SHGs for* 1 crore = 10 million; 1 lakh = 1,00,000; 100 lakhs = 1 crorevii

self-management by members and scal<strong>in</strong>g up of development activities and to enableaccess to <strong>in</strong>cre<strong>as</strong>ed resources from fund<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>stitutions.3.3 An exam<strong>in</strong>ation of the SHG federation models adopted by the lead<strong>in</strong>g NGOs revealsa variety of <strong>in</strong>novations. These <strong>in</strong>clude l<strong>in</strong>kage to the parent NGO-MFI, l<strong>in</strong>kage withexternal MFIs, community ownership of a Non-Bank<strong>in</strong>g F<strong>in</strong>ance Company (NBFC) andSHGs be<strong>in</strong>g reconstituted <strong>in</strong>to mutually aided credit and thrift cooperatives. Federationsof SHGs are now <strong>in</strong> a position to access funds even from wholesale MFIs. However,several of these <strong>in</strong>novations are one-off <strong>in</strong>itiatives <strong>in</strong>capable of e<strong>as</strong>y replication or, <strong>as</strong> <strong>in</strong>the c<strong>as</strong>e of the mutually-aided cooperatives, specific to the context of state <strong>in</strong> which theyhave been <strong>in</strong>troduced.3.4 The many possible comb<strong>in</strong>ations of formal and non-formal <strong>in</strong>stitutional channels thatreach MF for the poor through SHGs are a feature of a system where a suitable regulatoryenvironment of MF h<strong>as</strong> not developed and MFIs struggle to f<strong>in</strong>d an appropriate pathgiven the national and local constra<strong>in</strong>ts.4. Costs of SHG Promotion4.1 Estimates of costs of SHG promotion have been undertaken for 10 NGOs/projectsalong with a discussion of the factors <strong>in</strong>volved. A dist<strong>in</strong>ction is made between four majortypes of SHG “models”: (i) the “m<strong>in</strong>imalist” approach of banks and NBFCs promot<strong>in</strong>gmicrof<strong>in</strong>ance SHGs; (ii) large project <strong>in</strong>itiatives related to sav<strong>in</strong>gs and credit, capacitybuild<strong>in</strong>g and women’s empowerment; (iii) lead<strong>in</strong>g NGOs adopt<strong>in</strong>g a microf<strong>in</strong>ance plusapproach focus<strong>in</strong>g on livelihoods development; and (iv) a mixed category of SHGsformed through local <strong>in</strong>itiatives, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g SHGs promoted by the district developmentagency.4.2 Though <strong>in</strong>puts and contexts differ across the country, rough benchmarks for cost ofpromotion of SHGs have been proposed <strong>in</strong> the study. The available data suggests aconvergence of cost of promotion per SHG at around Rs. 4,000 for the m<strong>in</strong>imalist modelof pure bank l<strong>in</strong>kage and Rs. 10,000 to Rs. 12,000 with<strong>in</strong> a more comprehensiveempowerment framework. The cost of promotion of SHGs appears generally to be <strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>ewith the scale of support provided by various government agencies. Necessaryadjustments would, however, have to be made for particular regional, social and povertycontexts.4.3 Some other benchmarks that can be suggested: (i) period of support – 3 to 5 years;(ii) clients per field worker – 400 or 20 to 25 groups; (iii) m<strong>in</strong>imum scale of <strong>in</strong>terventionto justify costs <strong>in</strong>curred – 150 to 200 groups, or 2,500 to 3,000 members, <strong>in</strong> ageographically compact area.4.4 There are prospects for a reduction <strong>in</strong> these costs over time <strong>as</strong> SHG numbers <strong>in</strong>cre<strong>as</strong>e<strong>in</strong> an area and where <strong>as</strong>sociations of exist<strong>in</strong>g SHGs <strong>help</strong> to form new SHGs.viii

5. Susta<strong>in</strong>ability of SHGs and SHG-b<strong>as</strong>ed Institutions5.1 The susta<strong>in</strong>ability of SHGs and SHG-b<strong>as</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>stitutions is com<strong>in</strong>g under closescrut<strong>in</strong>y. However, f<strong>in</strong>ancial viability at the level of the SHGs is currently not an issue.SHG <strong>in</strong>come, though small, is matched by an extremely low cost of operations.5.2 The quality and <strong>in</strong>stitutional susta<strong>in</strong>ability of the SHGs promoted is more open toquestion. Even best practice NGOs generally place only about 50% of groups <strong>in</strong> thehighest category of performance, with 10-20% fail<strong>in</strong>g to take off. SHGs l<strong>in</strong>ked to banksdo not appear thus far to be able to e<strong>as</strong>ily graduate to (larger) <strong>in</strong>dividual loans under thebank’s normal lend<strong>in</strong>g programme. The lead<strong>in</strong>g NGOs covered <strong>in</strong> this study have ph<strong>as</strong>edout from some are<strong>as</strong> after l<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g SHGs to banks. There is, however, une<strong>as</strong>e about theability of SHGs to cont<strong>in</strong>ue to access funds from the banks and to <strong>help</strong> their membersmove along a growth path out of poverty.5.3 Nevertheless, SHGs l<strong>in</strong>ked to banks are emerg<strong>in</strong>g <strong>as</strong> a low cost option toma<strong>in</strong>stream delivery systems of f<strong>in</strong>ancial services for the poor. At the same time theevidence suggests MFIs lend<strong>in</strong>g to SHGs realise a poor return on their portfolio.5.4 Where SHGs have been formed <strong>in</strong>to federations, the operational self-sufficiency ofthe <strong>in</strong>termediary <strong>in</strong>stitutions h<strong>as</strong> yet to be demonstrated. The type of emerg<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>stitutions and their development is constra<strong>in</strong>ed by the exist<strong>in</strong>g regulatory framework forMF and the legal forms available <strong>in</strong> each state.5.5 The ph<strong>as</strong>e-out of NGOs from are<strong>as</strong> where SHGs have been federated h<strong>as</strong> proved tobe difficult <strong>in</strong> practice. The leadership and management of most SHG federations andcooperatives cont<strong>in</strong>ue to be <strong>in</strong> the hands of NGO staff. The development of the capacityof these <strong>in</strong>stitutions for self-management rema<strong>in</strong>s an important issue.6. Impact of SHG-b<strong>as</strong>ed MF programmes6.1 Comprehensive impact studies on the effectiveness of SHGs are virtually nonexistenteven for the best practice NGOs. Programme Management Information Systems(MIS) of NGOs are also generally not geared to provid<strong>in</strong>g substantive impact data.6.2 A major NABARD impact evaluation cover<strong>in</strong>g 560 members of 223 SHGs l<strong>in</strong>ked tobanks <strong>in</strong> 11 states showed that SHG members realized major <strong>in</strong>cre<strong>as</strong>es <strong>in</strong> <strong>as</strong>sets, <strong>in</strong>comeand employment. Also, women members were found to have become more <strong>as</strong>sertive <strong>in</strong>confront<strong>in</strong>g social evils and problem situations. Nearly half the poor member householdshad crossed the poverty l<strong>in</strong>e.6.3 Various other reviews and evaluations of SHG programmes suggest that SHGs have• provided access to credit to their members;• <strong>help</strong>ed to promote sav<strong>in</strong>gs and yielded moderate economic benefits;• reduced the dependence on moneylenders; and• resulted <strong>in</strong> empowerment benefits to women.ix

6.4 On the other hand field reports also suggest that• contrary to the vision for SHG development, SHGs are generally notcomposed of ma<strong>in</strong>ly the poorest families;• there is greater evidence of social empowerment rather than significantand consistent economic impact; and• f<strong>in</strong>ancial skills of group members have not developed <strong>as</strong> planned.6.5 Prelim<strong>in</strong>ary f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs from an <strong>in</strong>-depth impact evaluation of a non-SHG MF model(Share Microf<strong>in</strong>) show that half the families covered were found to be no longer poor. Asignificant discovery w<strong>as</strong> that the clients used <strong>as</strong> many <strong>as</strong> 17 different “paths” out ofpoverty <strong>as</strong> represented by different comb<strong>in</strong>ations of activities. It appears that “prov<strong>in</strong>gimpact” us<strong>in</strong>g “state of the art” techniques h<strong>as</strong> been found necessary for MFIs directly<strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> lend<strong>in</strong>g operations <strong>in</strong> order to access funds for their MF operations. The samepressure is not felt by SHG facilitators.6.6 It is clear that substantial capacity build<strong>in</strong>g is necessary at NGO and SHG level toundertake the study of program effectiveness. As additional layers of primary andsecondary federation are created, roles and responsibilities of various agents, MISrequirements and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>puts have to be planned and provided for these organizations<strong>as</strong> well.7. RecommendationsThe follow<strong>in</strong>g are<strong>as</strong> of <strong>in</strong>tervention for ICCO-Cordaid support for the SHG and MFsector may be considered:• Development of standards for SHGs• Support for MF and promotion of SHGs <strong>in</strong> poverty belt states• Development of loan products for MFIs work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> undeveloped states• Fund<strong>in</strong>g for state-level support <strong>in</strong>stitutions like APMAS and resource NGOs forSHG development• Research on SHG/SHG federation susta<strong>in</strong>ability• Cont<strong>in</strong>ued grant support for SHG promotionx

1. INTRODUCTIONThis paper seeks to exam<strong>in</strong>e the development of self-<strong>help</strong> groups (SHGs) and their role <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ancial services delivery <strong>in</strong> <strong>India</strong>. It is now a decade s<strong>in</strong>ce the National Bank forAgriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) piloted the SHG-bank L<strong>in</strong>kageProgramme to provide poor rural households access to bank<strong>in</strong>g services. The programmeh<strong>as</strong> grown <strong>in</strong> an exponential manner, particularly dur<strong>in</strong>g the p<strong>as</strong>t five years or so. WhileNGOs have taken the lead <strong>in</strong> form<strong>in</strong>g SHGs, a variety of f<strong>in</strong>ancial service promoters and<strong>in</strong>termediaries, official and non-official, are currently <strong>as</strong>sociated with the programme.Further, several central government m<strong>in</strong>istries and state governments have launchedprojects and schemes <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g the organisation of sav<strong>in</strong>gs and credit groups, usually ofpoor women, often <strong>as</strong> part of programmes supported by bilateral and multilateral agencyfund<strong>in</strong>g. Indeed, SHGs are currently seen <strong>as</strong> an essential and <strong>in</strong>tegral part not only off<strong>in</strong>ancial services delivery, but also <strong>as</strong> a channel for the delivery of non-f<strong>in</strong>ancial serviceswith<strong>in</strong> larger objectives of livelihoods promotion, community development and women’sempowerment.Barr<strong>in</strong>g a few exceptions, sav<strong>in</strong>gs and credit h<strong>as</strong> been used <strong>as</strong> a practical entry-po<strong>in</strong>tactivity around which to organise (poor) women <strong>in</strong>to SHGs. These SHGs are potential“micro-banks”, either on their own, or through higher levels of <strong>as</strong>sociation, capable ofus<strong>in</strong>g their own resources, grants and borrowed funds for f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>in</strong>termediation. Apartfrom access<strong>in</strong>g funds from the formal f<strong>in</strong>ancial sector, SHGs can also become a forumfor dissem<strong>in</strong>ation of development ide<strong>as</strong> and <strong>in</strong>formation, an <strong>as</strong>sociation for communitymobilisation or an organisational unit for l<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g up with other economic, social andpolitical <strong>in</strong>terventions.With<strong>in</strong> this role for SHGs a range of models and approaches have emerged, represent<strong>in</strong>gdifferent methods of ensur<strong>in</strong>g effectiveness and susta<strong>in</strong>ability of this community<strong>in</strong>stitution. These models envisage solely f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>in</strong>termediation or <strong>in</strong>clude other nonf<strong>in</strong>ancialelements <strong>as</strong> well. Given the diversity of approaches be<strong>in</strong>g practised it isdesirable to exam<strong>in</strong>e costs and benefits and prospects of long-term function<strong>in</strong>g of SHGsand the emerg<strong>in</strong>g SHG federations, particularly those promoted by lead<strong>in</strong>g NGOs. Thiswill contribute to an understand<strong>in</strong>g of “best practice” <strong>in</strong> SHG development towards widerreplication of the SHG model. It is also expected to <strong>help</strong> <strong>in</strong> direct<strong>in</strong>g funds from donorsand other f<strong>in</strong>ance providers <strong>in</strong>to the future development of effective <strong>in</strong>stitutions andactivities <strong>in</strong> the microf<strong>in</strong>ance sector.This study supplements counterpart studies undertaken by I/C Consult, The Hague, TheNetherlands on the self-<strong>help</strong> group landscape <strong>in</strong> <strong>India</strong> (Bosch, 2001; Bosch and Damen,2000). The study h<strong>as</strong> been undertaken by <strong>Sa</strong>-<strong>Dhan</strong>, an <strong>as</strong>sociation of <strong>India</strong>n communitydevelopment f<strong>in</strong>ance <strong>in</strong>stitutions, on behalf of ICCO and Cordaid, two Dutch cof<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>gagencies that support a large variety of NGO programmes aimed at promot<strong>in</strong>g1

susta<strong>in</strong>able self-<strong>help</strong> groups. An <strong>in</strong>cre<strong>as</strong><strong>in</strong>g number of <strong>Sa</strong>-<strong>Dhan</strong> members are alsodeliver<strong>in</strong>g f<strong>in</strong>ancial services through SHGs.1.1 Objectives of the studyThe pr<strong>in</strong>cipal objective of this study is to contribute to a consistent and relevant fund<strong>in</strong>gpolicy for ICCO and Cordaid, which encomp<strong>as</strong>ses the promotion of SHGs <strong>as</strong> a vehiclefor development and emancipation.The study also attempts to provide a current perspective on the function<strong>in</strong>g of SHGsengaged <strong>in</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>in</strong>termediation, and their support <strong>in</strong>stitutions, for <strong>Sa</strong>-<strong>Dhan</strong> membersand the many and varied stakeholders <strong>in</strong> the SHG movement <strong>in</strong> <strong>India</strong> with the objectiveof direct<strong>in</strong>g future policy and fund<strong>in</strong>g for SHGs.The study conta<strong>in</strong>s an <strong>in</strong>quiry <strong>in</strong>to the cost of promotion of SHGs, the impact of SHGprogrammes and the susta<strong>in</strong>ability of SHG-b<strong>as</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>stitutions and frameworks forf<strong>in</strong>ancial services delivery <strong>in</strong> <strong>India</strong>. The study also undertakes a critical analysis of thepaths of SHG development emerg<strong>in</strong>g from current practices <strong>in</strong> different regionalcontexts.1.2 Methodology of the studyThe study addresses three ma<strong>in</strong> issues:• Efficiency: What can be said about the average cost of SHG promotion both with andwithout emph<strong>as</strong>is on social and political empowerment? What difference does thecredit plus approach make to average SHG promotion costs?• Effectiveness: What is known through results of <strong>as</strong>sessment studies of the effects andimpact of SHG promotion? What is known about the results of monitor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dicatorsof impact?• Susta<strong>in</strong>ability: What k<strong>in</strong>d of susta<strong>in</strong>ability or ph<strong>as</strong>e out strategy is employed byNGOs? The strategies considered <strong>in</strong>clude: (i) bank l<strong>in</strong>kage; (ii) transformation ofNGOs promot<strong>in</strong>g SHGs <strong>in</strong>to MFIs; and (iii) creation of f<strong>in</strong>ancially <strong>in</strong>dependentfederations of SHGs.The study sets out to understand SHG development through learn<strong>in</strong>g from theexperiences of selected NGOs, projects and <strong>in</strong>stitutions generally accepted <strong>as</strong> form<strong>in</strong>g apart of the vanguard of the SHG movement. At the same time it seeks to place the visionand practice of SHG promotion <strong>in</strong> the context of global issues and <strong>in</strong>ternational bestpractice of microf<strong>in</strong>ance. It makes a prelim<strong>in</strong>ary attempt to exam<strong>in</strong>e SHGs through thelens of cost-effectiveness, impact and susta<strong>in</strong>ability and to detail the emerg<strong>in</strong>g paths forfuture SHG development.2

The study h<strong>as</strong> drawn extensively on recent literature on SHGs and microf<strong>in</strong>ance <strong>in</strong>identify<strong>in</strong>g experiences, issues and prospects of the SHG movement. It is not b<strong>as</strong>ed onprimary data. However, by participat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> several SHG and federation meet<strong>in</strong>gs, theauthor h<strong>as</strong> brought a field perspective to the study. The study is b<strong>as</strong>ed on data obta<strong>in</strong>edfrom seven selected NGOs <strong>as</strong> well <strong>as</strong> data for the various apex organisations. This h<strong>as</strong>been supplemented with <strong>in</strong>terviews, f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs of unpublished notes and reports, <strong>in</strong>ternalevaluations, project submissions, workshop presentations and proceed<strong>in</strong>gs and othersimilar “grey” material. Comprehensive <strong>in</strong>terviews with chief executives and staff of adozen other NGOs/ agencies have provided useful <strong>in</strong>sights <strong>in</strong>to the SHG phenomenon. Alist of organizations visited and <strong>in</strong>dividuals met is given <strong>in</strong> Appendix 1.S<strong>in</strong>ce the SHG movement is still comparatively new, documentation of SHG experienceis limited and not much systematic research h<strong>as</strong> taken place. As a result the study h<strong>as</strong>been constra<strong>in</strong>ed by the variable quality of data available. This h<strong>as</strong> prevented a morestructured and rigorous analysis.1.3 Organisation of the ReportChapter 2 presents the doma<strong>in</strong> and outreach of SHGs <strong>in</strong> the microf<strong>in</strong>ance sector and <strong>in</strong>poverty alleviation. It <strong>in</strong>troduces the pr<strong>in</strong>cipal actors that promote and fund SHGs and theNGOs covered by the study.Chapter 3 sets out NGO strategies for SHG development, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g bank l<strong>in</strong>kage and avariety of forms of SHG federations l<strong>in</strong>ked to other MFIs. It maps the structures of<strong>in</strong>termediation through which funds flow to SHGs and SHG federations from apexlend<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>stitutions.Chapter 4 discusses estimates of costs of promotion under different models - m<strong>in</strong>imalist,empowerment and livelihoods development - and develops benchmarks for costs of SHGpromotion.Chapter 5 exam<strong>in</strong>es, from available evidence, the prospects of long-term susta<strong>in</strong>ability ofthe strategies adopted by the different NGOs for SHGs and SHG federations promoted bythem.Chapter 6 discusses the f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs of various impact <strong>as</strong>sessments of SHGs engaged <strong>in</strong> MFand identifies the capacity build<strong>in</strong>g needs of SHG-b<strong>as</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>stitutions for impact<strong>as</strong>sessment.Chapter 7 makes recommendations for donor policy towards the future development ofSHGs.3

2. DEVELOPMENT OF SELF-HELP GROUPS IN INDIA – AN OVERVIEW2.1 Features of SHGsA variety of group-b<strong>as</strong>ed approaches that rely on social collateral and its many enabl<strong>in</strong>gand cost-reduc<strong>in</strong>g effects are a feature of modern microf<strong>in</strong>ance (MF). It is possible todist<strong>in</strong>guish between: (a) groups that are primarily geared to deliver f<strong>in</strong>ancial servicesprovided by microf<strong>in</strong>ance <strong>in</strong>stitutions (MFIs) to <strong>in</strong>dividual borrowers (such <strong>as</strong> the jo<strong>in</strong>tliability groups of Grameen and the NGO-banks of Bangladesh); and (b) groups thatmanage and lend their accumulated sav<strong>in</strong>gs and externally leveraged funds to theirmembers.While the term ‘self-<strong>help</strong> group’ or SHG can be used to describe a wide range off<strong>in</strong>ancial and non-f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>as</strong>sociations, <strong>in</strong> <strong>India</strong> it h<strong>as</strong> come to refer to a form ofAccumulat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Sa</strong>v<strong>in</strong>g and Credit Association (ASCA) (after Bouman, 1995) promoted bygovernment agencies, NGOs or banks. Thus, SHGs fall with<strong>in</strong> the latter category ofgroups described above.A dist<strong>in</strong>ction can be made between different types of SHGs accord<strong>in</strong>g to their orig<strong>in</strong> andsources of funds (Appendix 2). Several SHGs have been carved out of larger groups,formed under pre-exist<strong>in</strong>g NGO programmes for thrift and credit or more broad-b<strong>as</strong>edactivities. Some have been promoted by NGOs with<strong>in</strong> the parameters of the bank l<strong>in</strong>kagescheme but <strong>as</strong> part of an <strong>in</strong>tegrated development programme. Others have been promotedby banks and the district rural development agencies (DRDAs). Still others have beenformed <strong>as</strong> a component of various physical and social <strong>in</strong>fr<strong>as</strong>tructure projects. Some of thecharacteristic features of SHGs currently engaged <strong>in</strong> MF are given below:• An SHG is generally an economically homogeneous group formed through a processof self-selection b<strong>as</strong>ed upon the aff<strong>in</strong>ity 1 of its members.• Most SHGs are women’s groups with membership rang<strong>in</strong>g between 10 and 20.• SHGs have well-def<strong>in</strong>ed rules and by-laws, hold regular meet<strong>in</strong>gs and ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>records and sav<strong>in</strong>gs and credit discipl<strong>in</strong>e.• SHGs are self-managed <strong>in</strong>stitutions characterised by participatory and collectivedecision mak<strong>in</strong>g.NGO-promoted SHGs were often nested <strong>in</strong> sangh<strong>as</strong> or village development groupsundertak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>tegrated development activities. As they have developed, SHGs or sangh<strong>as</strong>have been grouped <strong>in</strong>to larger clusters and multi-village federations for f<strong>in</strong>ancial and nonf<strong>in</strong>ancialactivities.1 The question of aff<strong>in</strong>ity is, however, a contentious one. Several practitioners <strong>as</strong>cribe the “poor” quality ofnew SHGs be<strong>in</strong>g formed (particularly by banks and state agencies <strong>as</strong> part of a target-driven approach) tothe lack of aff<strong>in</strong>ity among their members. In fact, a lead<strong>in</strong>g NGO calls groups it promotes self-<strong>help</strong> aff<strong>in</strong>itygroups (SAGs) rather than SHGs. On the other hand, the concern with aff<strong>in</strong>ity can translate <strong>in</strong>to formationof c<strong>as</strong>te-b<strong>as</strong>ed SHGs (rather than formation of groups b<strong>as</strong>ed upon shared poverty conditions), with thepotential negative ramifications of c<strong>as</strong>te politics.4

2.2 SHG-Bank L<strong>in</strong>kage2.2.1 Bank L<strong>in</strong>kage Scheme – The ModelThe SHG-bank L<strong>in</strong>kage Programme h<strong>as</strong> its orig<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong> a GTZ-sponsored project <strong>in</strong>Indonesia. Launched <strong>in</strong> 1992 <strong>in</strong> <strong>India</strong>, early results achieved by SHGs promoted byNGOs such <strong>as</strong> MYRADA, prompted NABARD to offer ref<strong>in</strong>ance to banks for collateralfreeloans to groups, progressively up to four times the level of the group's sav<strong>in</strong>gsdeposits. SHGs thus "l<strong>in</strong>ked" became micro-banks able to access funds from the formalbank<strong>in</strong>g system. The l<strong>in</strong>kage permitted the reduction of transaction costs of banksthrough the externalisation of costs of servic<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividual loans and also ensur<strong>in</strong>g theirrepayment through the peer pressure mechanism.The programme encomp<strong>as</strong>ses three broad models of l<strong>in</strong>kage:Model I: Bank - SHG - MembersIn this model the bank itself promotes and nurtures the self-<strong>help</strong> groups until they reachmaturity. It accounted for 16% of cumulative bank loan provided till the end of March2002.Model II: Bank - Facilitat<strong>in</strong>g Agency - SHG - MembersHere groups are formed and supported by NGOs or government agencies. Thedom<strong>in</strong>ant model, it accounted for 75% of cumulative loans of banks by March2002.Model III: Bank - NGO-MFI - SHG - MembersIn this model NGOs act <strong>as</strong> both facilitators and MF <strong>in</strong>termediaries, and often federateSHGs <strong>in</strong>to apex organisations to facilitate <strong>in</strong>ter-group lend<strong>in</strong>g and larger access to funds.Cumulative bank loans through this channel were 9% of total by March 2002.Another model h<strong>as</strong> been piloted recently by NABARD for facilitat<strong>in</strong>g theformation of SHGs for bank l<strong>in</strong>kage <strong>in</strong> are<strong>as</strong> where there are no NGOs. This<strong>in</strong>volves us<strong>in</strong>g the services of committed <strong>in</strong>dividual volunteers identified by bankbranches.2.2.2 Outreach of SHG-bank l<strong>in</strong>kageDetails of outreach of the SHG-bank l<strong>in</strong>kage programme are given <strong>in</strong> Table 2.1. While theSHG-bank l<strong>in</strong>kage programme w<strong>as</strong> slow to take off, <strong>in</strong> recent years it h<strong>as</strong> expandedexponentially. By the end of March 2001, its coverage had more than doubled over theprevious year to 4.5 million families <strong>in</strong> nearly 2.64 lakh 2 SHGs, with 90% womenmembers. These SHGs had availed of Rs. 480.87 crores <strong>in</strong> cumulative bank loans. The2 1 lakh = 100,000; 10 lakhs = 1 million; 100 lakhs or 10 million = 1crore5

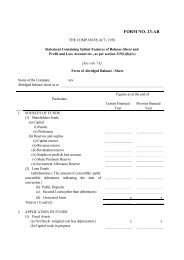

average loan per SHG w<strong>as</strong> Rs. 18,227 3 and per family Rs. 1,072. On-time repayment bySHGs w<strong>as</strong> reported to be over 95%.Outreach of SHG-Bank L<strong>in</strong>kageAs on As on As on31.3.2000 31.3.2001 31.3.20021. No. of groups 114,775 263,825 461,4782. Coverage 1.9 4.5 7.8(no. of families) (million)3. % of women’s groups 85 90 904. Cumulative bank 192.98 480.87 1,026.30loans (Rs. crores)5. No. of NGO partners 718 1030 2,1556. Repayment rate: > 95 > 95 > 95(from SHG to Bank/NGO) (%)7. Average loan per SHG 16,814 18,227 22,240(Rs.)8. Average loan per family 1,016 1,072 1,316(Rs.)Source: NABARD & Microf<strong>in</strong>ance, 2000-2001 and 2001-2002Accord<strong>in</strong>g to the latest data, by the end of March 2002 the coverage of the SHG-bankl<strong>in</strong>kage programme had <strong>in</strong>cre<strong>as</strong>ed to 7.8 million families <strong>in</strong> 461,478 SHGs, with 90%women members, which had availed of Rs. 1,026.30 crores <strong>in</strong> cumulative bank loans. Ontimerepayment cont<strong>in</strong>ued to be over 95 %. This programme <strong>in</strong>volved 2,155 NGOs andother self-<strong>help</strong> promot<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>stitutions. It is claimed to be currently the largest MFprogramme worldwide.NABARD's corporate mission is to make available MF services to 20 million poorhouseholds, or one-third of the total poor <strong>in</strong> the country, by 2008. However, there is, atpresent, a high degree of concentration <strong>in</strong> the southern states with just two states, AndhraPradesh and Tamil Nadu account<strong>in</strong>g for more than 66 % of the SHGs receiv<strong>in</strong>g loansthrough bank l<strong>in</strong>kage, with the coverage <strong>in</strong> Andhra Pradesh be<strong>in</strong>g nearly 53% of totalSHGs. These states have a history of women’s enterprise, higher levels of literacy and3 48.50 <strong>India</strong>n Rupees (Rs.) = 1 US $6

strong cooperative <strong>in</strong>stitutions. SHG-bank l<strong>in</strong>kage h<strong>as</strong> not <strong>as</strong> yet made an impact <strong>in</strong> thepoverty belt of the northern, central and e<strong>as</strong>tern regions.The outreach of SHG-bank l<strong>in</strong>kage may seem to be impressive, but <strong>in</strong> the context of themagnitude of poverty <strong>in</strong> <strong>India</strong> and the flow of funds for poverty alleviation it represents avery small <strong>in</strong>tervention. An estimated 60 million <strong>India</strong>n rural households may be cl<strong>as</strong>sified<strong>as</strong> poor. It is well known that only about one-third of SHG members are able to accessloans <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>itial years. Thus of the 4.5 million families covered by March 2001 andeligible for bank loans, only about 1.5 million would have received loans of an average ofRs. 3,000 each. The benefit of bank f<strong>in</strong>ance is thus realised by a much smaller number offamilies. Other members, however, may benefit through sav<strong>in</strong>gs and petty loans from theSHGs’ <strong>in</strong>ternal fund.Rs. 53,504 crores w<strong>as</strong> expected to be disbursed for agriculture and allied activities by thebank<strong>in</strong>g system dur<strong>in</strong>g 2000-2001 4 . Dur<strong>in</strong>g the same period, disbursements under bankl<strong>in</strong>kage were Rs.250.62 crores or less than half of one per cent of this figure. Similarly,disbursements of bank loans under the poverty-focused self-employment programme,Swarna Jayanti Swarozgar Yojana (SGSY) 5 , meant for families below the poverty l<strong>in</strong>e,were Rs. 642.34 crores or more than two and a half times the advances under SHG-bankl<strong>in</strong>kage. Thus while the SHG programme h<strong>as</strong> made notable progress <strong>in</strong> provid<strong>in</strong>g loans tolargely poor families, it h<strong>as</strong> not significantly <strong>in</strong>cre<strong>as</strong>ed the credit flow to rural are<strong>as</strong>.2.3 Institutions Fund<strong>in</strong>g and Promot<strong>in</strong>g SHGs2.3.1 MF WholesalersThere are half-a-dozen apex <strong>in</strong>stitutions provid<strong>in</strong>g funds and capacity-build<strong>in</strong>g supportfor MF through various MFIs. Under various schemes they provide bulk loans to retailNGO-MFIs and other emerg<strong>in</strong>g forms of microf<strong>in</strong>ance <strong>in</strong>stitutions (MFIs) such <strong>as</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ancial cooperatives, mutually aided cooperative thrift societies (MACTS), andfederations of SHGs. Detailed particulars of their loan schemes and terms are given <strong>in</strong>Appendix 3. A similar approach to NABARD’s bank l<strong>in</strong>kage, us<strong>in</strong>g NGOs/MFIs <strong>as</strong><strong>in</strong>termediaries (model III <strong>in</strong> section 2.2.1 above) h<strong>as</strong> also been adopted by other bulklend<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>stitutions such <strong>as</strong> the Small Industries Bank of <strong>India</strong> (SIDBI), R<strong>as</strong>htriya MahilaKosh (RMK), Hous<strong>in</strong>g and F<strong>in</strong>ance Development Corporation (HDFC), Hous<strong>in</strong>g andUrban Development Corporation (HUDCO), R<strong>as</strong>htriya Grameen Vik<strong>as</strong> Nidhi (RGVN)and Friends of Women’s World Bank<strong>in</strong>g (FWWB).NABARD: Apart from giv<strong>in</strong>g the lead <strong>in</strong> pilot<strong>in</strong>g the SHG-bank l<strong>in</strong>kage and the ref<strong>in</strong>anceof loans by banks to SHGs, NABARD is engaged <strong>in</strong> fulfill<strong>in</strong>g a variety of promotion andsupport functions <strong>as</strong> the apex bank for agriculture and rural development. These <strong>in</strong>clude:• develop<strong>in</strong>g a conducive policy framework4 These data and those below are from NABARD Annual Report 2000-2001.5 This, <strong>in</strong> turn, is currently be<strong>in</strong>g implemented on a smaller scale than its predecessor, the IRD programme,which closed <strong>in</strong> 1999 and under which annual bank loans were <strong>in</strong> excess of Rs. 1,500 crores.7

• tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and sensitis<strong>in</strong>g bank officers• capacity-build<strong>in</strong>g support to NGOs, SHGs and banks• f<strong>in</strong>ancial support to NGOs for SHG promotion• provision of revolv<strong>in</strong>g fund <strong>as</strong>sistance to MFIs• evaluation studies and dissem<strong>in</strong>ation of SHG best practicesA Microf<strong>in</strong>ance Development Fund with a corpus of Rs. 100 crores h<strong>as</strong> been establishedto scale up the bank l<strong>in</strong>kage programme, build expertise <strong>in</strong> MF and support the evolutionof regulatory and support mechanisms for MFIs. So far utilization h<strong>as</strong> been low with 330NGOs supported to the extent of Rs. 4 crores by October 2001. NABARD h<strong>as</strong> alsoreceived the first tranche of a DM 3 million GTZ grant for capacity build<strong>in</strong>g ofNABARD and its partner agencies.SIDBI: SIDBI h<strong>as</strong> set up the Foundation for Microcredit. By 31 March 2000 it hadsanctioned aggregate <strong>as</strong>sistance of Rs. 52.76 crores to 160 MFIs. It also provides capacitybuild<strong>in</strong>g support to eligible MFIs. It h<strong>as</strong> s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>in</strong>cre<strong>as</strong>ed the fund<strong>in</strong>g available forextend<strong>in</strong>g loans and equity to MFIs to Rs. 500 crores.RMK: A fund set up <strong>in</strong> 1993 by the Department of Women and Child Development,Government of <strong>India</strong>, RMK provides loans to NGOs for on-lend<strong>in</strong>g to womenbeneficiaries. It had disbursements of nearly 60 crores by March 2000. Its loans attractthe lowest rates of <strong>in</strong>terest at 8 % with concessions for timely repayment. Grants for SHGpromotion are also provided.HUDCO and HDFC: These corporations are ma<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> hous<strong>in</strong>g f<strong>in</strong>ance,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g f<strong>in</strong>ance to economically weaker sections. HDFC had Rs. 80 crores of loansoutstand<strong>in</strong>g but its portfolio is not directed only at the rural poor.RGVN: RGVN is a non-profit society formed <strong>in</strong> April 1990. Operat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the neglectednorth-e<strong>as</strong>tern region of the country, it is the only national donor agency work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> thisremote area. Sponsored by some of the biggest f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>in</strong>stitutions like the IndustriesDevelopment Bank of <strong>India</strong> (IDBI), Industrial Credit and Investment Corporation of<strong>India</strong> (ICICI) and SIDBI, it also recycles grant funds by extend<strong>in</strong>g “returnable grants” toNGOs. It outstand<strong>in</strong>g loans were Rs. 2.31 crores at the end of March 2001.FWWB: FWWB is a non-profit organisation set up <strong>in</strong> 1982 <strong>as</strong> an affiliate of Women’sWorld Bank<strong>in</strong>g. It started a revolv<strong>in</strong>g loan fund <strong>in</strong> 1989. It had outstand<strong>in</strong>g loans of Rs.17.41 crores to various MFIs by March 2001. It h<strong>as</strong> also availed of a Cordaid loanrepayable <strong>in</strong> rupees at 9 % <strong>in</strong>terest.2.3.2 Donors and International LendersOver the years a large number of the well-known <strong>in</strong>ternational donors have supportedmicrof<strong>in</strong>ance (MF) programmes run by NGOs. Several large projects are also promot<strong>in</strong>gSHGs through multilateral fund<strong>in</strong>g. These donors provide adm<strong>in</strong>istrative support andcapacity-build<strong>in</strong>g grants <strong>as</strong> well <strong>as</strong> revolv<strong>in</strong>g loan funds to NGOs. In addition to the8

sources above, about Rs. 150 crores of funds are available through this route. With theliberalisation of guidel<strong>in</strong>es for external commercial borrow<strong>in</strong>g, MFIs are now borrow<strong>in</strong>gfrom various <strong>in</strong>ternational lenders such <strong>as</strong> Deutsche Bank, Rabobank Foundation andOikocredit.2.3.3 GovernmentThe major government programme promot<strong>in</strong>g SHGs and channel<strong>in</strong>g large funds forpoverty reduction is the SGSY programme. Other state and central governmentprogrammes too have promoted SHGs <strong>in</strong> large numbers, especially <strong>in</strong> Andhra Pradesh.Some of the issues related to these programmes are discussed <strong>in</strong> subsequent chapters.2.3.4 NGOsAll over the country NGOs have been promot<strong>in</strong>g SHGs for sav<strong>in</strong>gs and credit andother social and economic programmes for at le<strong>as</strong>t the p<strong>as</strong>t 20-25 years. Over 2000NGOs are currently <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> the bank-l<strong>in</strong>kage programme. The lead<strong>in</strong>g SHGpromot<strong>in</strong>g NGOs are a mixed group that <strong>in</strong>cludes pure SHG promoters, NGOsfunction<strong>in</strong>g <strong>as</strong> MF <strong>in</strong>termediaries, and NGOs that have promoted non-profit and forprofitnon-bank<strong>in</strong>g companies for on-lend<strong>in</strong>g grant and borrowed funds to SHGs andSHG-b<strong>as</strong>ed federations. However, the majority of them act <strong>as</strong> promoters and facilitatorsof SHGs. Of the SHGs l<strong>in</strong>ked to banks by March 2002, 75% have been formed by NGOfacilitators and only 9% by NGO <strong>in</strong>termediaries.One of the major issues relat<strong>in</strong>g to the function<strong>in</strong>g of NGOs <strong>as</strong> MFIs is the absence ofan appropriate legal form that the NGO can adopt to carry on MF activity. (A note on thelegal form of MFIs <strong>in</strong> <strong>India</strong> is given at Appendix 4).Seven NGOs promot<strong>in</strong>g SHGs are covered <strong>in</strong> this study 6 . These are PRADAN, NavBharat Juvak Kendra (NBJK), Holy Cross Social Service Centre (HCSSC), MYRADA,OUTREACH, DHAN Foundation and Association of <strong>Sa</strong>rva Seva Farms (ASSEFA). Adetailed profile of their operations and outreach is given <strong>in</strong> Table 2.1. For the vision ofthe NGOs and the nature of the SHG model they are promot<strong>in</strong>g see Chapter 3. Three ofthe NGOs are ICCO/Cordaid partners. Four of the NGOs operate <strong>in</strong> Tamil Nadu,Karnataka and partly <strong>in</strong> Andhra Pradesh. Three NGOs, viz., PRADAN, NBJK andHCSSC, operate <strong>in</strong> Jharkhand and Bihar. These NGOs are presently promot<strong>in</strong>g thousandsof SHGs with the support of a wide range of donor agencies. The succeed<strong>in</strong>g chapters arelargely b<strong>as</strong>ed upon data and <strong>in</strong>sights on SHG development provided by these NGOs.While these NGOs provide <strong>in</strong>stances of largely sound practice, they are notrepresentative of the thousands of other NGOs also promot<strong>in</strong>g SHGs and their6 With the exception of DHAN Foundation, the author visited all the other NGOs dur<strong>in</strong>g the course of thestudy.9

organizational structure and the nature and scale of their operations is not e<strong>as</strong>ilyreplicable.10

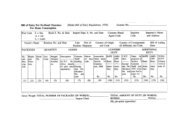

Table 2.1Profile of Operations and Outreach of selected NGO Promoters of SHGsS.No.ParticularsNBJKHazaribagh,JharkhandHoly CrossSSCJharkhandOUTREACHBangalore,KarnatakaDHANFoundation,Madurai,T.N.ASSEFA(<strong>Sa</strong>rvodayaNanof<strong>in</strong>ance)Chennai, T.N.PRADANNew DelhiMYRADABangalore,KarnatakaYear of data March 2001 Dec. 2001 July 2001 July 2001 March 2001 March 2001 Dec. 20001. NGO legal form/ MFfunctionSociety.NGO-MFIon-lends toSHGsSociety.PromotesSHG bankl<strong>in</strong>kageSociety, NGO-MFI lendsthrough SHGfederationsTrust.Promoter ofSHG/SHGfederationsSociety/trust.NBFC ownedby SHG feds.(trusts)Society.PromotesSHG bankl<strong>in</strong>kageSociety.Bank l<strong>in</strong>kage+ promoterof MF Co.2. Area of coverage 5 districts 450 villages/ 3 states 1901 villages 10 projects 18 districts 16 districtshamlets(14 blocks)3. No. of SHGs formed 732 1,513 1,400 5,194 2,779 2,752 4,8333a. Men’s groups 0 51 20 0 0 0 4093b. Women’s groups 732 1,460 1,380 5,194 2,779 2,752 4,1813c. Mixed groups 0 2 0 0 0 0 2434. Total SHG13,927 21,240 80,263 54,341 38,000 85,427membership5. % age of women 100% 97% 97% 100% 100% 100% 85-90%members6. No. of SHGs l<strong>in</strong>kedto banksNil825 400 2,056 601 821 1,771(Mar. 2001)7. Total amount lent bybanks (direct toSHGs/Feds) (Rs.)Nil2,50,00,000 n.a. 7,14,00,000 n.a. n.a 7,09,59,5958. SHG loan from NGO<strong>as</strong>sociates (Rs.)NilNil Nil Nil Nil Nil 87,09,000(<strong>Sa</strong>nghamitra)9. No. of federations of Nil40 (nonf<strong>in</strong>ancial)60 CLAs 1530, of which 19 n.a. 117 (non-SHGs promoted(block level) regd. <strong>as</strong> MBTsf<strong>in</strong>ancial)10. No. of MF field staff n.a. 40 7 n.a. 207 (10 SNF) n.a. n.a(contd.)11

Table 2.1 (contd.)S.No.ParticularsNBJKHazaribagh,JharkhandHoly CrossJharkhandOUTREACHBangalore,KarnatakaDHANFoundation,MaduraiASSEFA(<strong>Sa</strong>rvodayaNanof<strong>in</strong>ance)PRADANMYRADABangalore,Karnataka11. Total sav<strong>in</strong>gs ofSHGs (to date) (Rs.)12. Average <strong>Sa</strong>v<strong>in</strong>gs perSHG (to date) (Rs.)13. Loans outstand<strong>in</strong>g(Rs.)14. Average loanoutstand<strong>in</strong>g perSHG (Rs.)15. Current SHGrepayment rate16. Rate of <strong>in</strong>terest paidby SHGs17. Range of groups<strong>in</strong>ternal lend<strong>in</strong>g rate18. Selected otheractivities85,99,54911,7481,25,58,351(NBJK)80,00,000 2,75,00,000 10,67,00,000 5,15,61,000 n.a. 11,79,42,6725,288 19,643 20,543 18,554 n.a. 24,404Nil 75,00,000(OUTREACHloans only)20,75,00,000(externallysourced)17,156 n.a n.a. 39,950(externallysourced)3,09,04,956(SNF) (Jan.2002)Nil Niln.a. n.a. n.a.85% >90% 100% 98% 100% n.a. 98%18% (toNGO)12% (bankl<strong>in</strong>kage)20%(to CLAs)n.a.15% 12% (bankl<strong>in</strong>kage)24% 24-36% 24% n.a. As per group 24%decisionRural Irrigation Watershed Hous<strong>in</strong>g, Social security Irrigated<strong>in</strong>dustries and land programme, <strong>in</strong>surance, schemes, agriculture,programme, dev., <strong>in</strong>come livelihood and bus<strong>in</strong>ess hous<strong>in</strong>g, watershedwatershed generation, PRA tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, promotion, dairy<strong>in</strong>g, water development,development, human res. crop risk and <strong>in</strong>come harvest<strong>in</strong>g, villagemarket<strong>in</strong>g, dev., health cattlegeneration market<strong>in</strong>g of enterprises,tribal dev. and medical <strong>in</strong>surance, andagricultural humanawareness, services, enterprise agricultural goods, resourcecapacity human rights development, development community and development.build<strong>in</strong>g. counsel<strong>in</strong>g. agro services. programme. <strong>in</strong>ternaltra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g.Computed from: 1. <strong>Sa</strong>-<strong>Dhan</strong> data b<strong>as</strong>e. 2. Annual reports. 3. Data/<strong>in</strong>formation provided dur<strong>in</strong>g the study12% (bankl<strong>in</strong>kage)24%Naturalresourcemanagementhealth andeducationprogramme,PRA,tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g.12

3. PATHS OF SHG DEVELOPMENT: NGO STRATEGIES AND STRUCTURESFOR FINANCIAL INTERMEDIATIONThe objectives of SHG promotion <strong>in</strong> <strong>India</strong> by NGOs are expressed <strong>in</strong> a variety of ways withlivelihoods and empowerment at the centre. Barr<strong>in</strong>g a few exceptions, these NGOs have been<strong>in</strong>volved with microf<strong>in</strong>ance (MF) along with health, education and natural resourcemanagement often <strong>as</strong> part of an <strong>in</strong>tegrated approach 7 . However, NGOs are under pressure toaddress the question of f<strong>in</strong>ancial susta<strong>in</strong>ability of their MF programmes, an issue that is<strong>in</strong>cre<strong>as</strong><strong>in</strong>gly be<strong>in</strong>g raised by <strong>in</strong>ternational donors and domestic fund<strong>in</strong>g sources. It h<strong>as</strong>become necessary for NGOs to demonstrate that their microf<strong>in</strong>ance programmes can becomeoperationally and f<strong>in</strong>ancially self-sufficient. At the same time NGOs are constra<strong>in</strong>ed by thequestion of which legal form (most NGOs have been work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>as</strong> registered not-for-profitsocieties) to adopt for cont<strong>in</strong>ued operations <strong>in</strong> this sector. This is further tempered by the NGOobjective of creat<strong>in</strong>g community owned and managed f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>in</strong>stitutions built upon the SHGconcept. These pressures have brought about a period of transition <strong>as</strong> NGOs struggle to discoverthe appropriate <strong>in</strong>stitutional structure, both for themselves and the community <strong>in</strong>stitutionspromoted by them, given the conditions attached to various sources of funds and local andnational legal and regulatory provisions.Table 3.1 gives the vision and organisational details of SHG models promoted by the sevenlead<strong>in</strong>g NGOs covered by this study. For the flow of f<strong>in</strong>ancial resources, the vision <strong>in</strong>variably<strong>in</strong>volves a l<strong>in</strong>kage between the <strong>in</strong>formal SHGs and formal or ma<strong>in</strong>stream structures off<strong>in</strong>ancial services delivery. With the exception of NBJK all the NGOs have been at theforefront of the SHG- bank l<strong>in</strong>kage programme. However, there is a divergence between thelong-term paths of SHG development envisaged by the different SHG promoters. Therationale for these is discussed below.While SHGs promoted by these NGOs are part of a “microf<strong>in</strong>ance plus” approach, two broadpaths for long-term SHG <strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>in</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>in</strong>termediation can be identified:(i) SHGs l<strong>in</strong>ked directly to banks on a permanent b<strong>as</strong>is;(ii) SHGs/federations of SHGs l<strong>in</strong>ked to various types of MFIs.3.1 SHGs L<strong>in</strong>ked Directly to BanksThis is the b<strong>as</strong>ic model <strong>in</strong> which an SHG, promoted by an NGO or other <strong>in</strong>stitution, canaccess a multiple of its sav<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> the form of loans or c<strong>as</strong>h credit limits from the rural bankbranch. The SHG then on-lends the funds to its members.The SHG model is a sav<strong>in</strong>gs-led and sav<strong>in</strong>gs-l<strong>in</strong>ked credit model, with a m<strong>in</strong>imum sav<strong>in</strong>gsperiod of 6 months prior to the availability of bank credit 8 . The quantum of credit available to7 Many of these established NGOs have <strong>in</strong> the p<strong>as</strong>t supported SHGs or other community organisations <strong>in</strong> aprogramme of “poverty lend<strong>in</strong>g” (Kilby, et al., 2000) which w<strong>as</strong> characterised by objectives that give higherpriority to social outreach than f<strong>in</strong>ancial susta<strong>in</strong>ability. Revolv<strong>in</strong>g loan fund grants, earmarked for target groups,were managed and held <strong>in</strong> trust by NGOs until community capacity for self-management w<strong>as</strong> developed. Anunclear vision and weak management of funds led to a failure to develop the necessary community capacity and“ownership” towards NGO ph<strong>as</strong>e-out. In many c<strong>as</strong>es this also led to the erosion of community funds. Theopportunity to access loan funds through sources like bank l<strong>in</strong>kage and alternative examples of successfulmicrof<strong>in</strong>ance practice have led to donors generally do<strong>in</strong>g away with the provision of revolv<strong>in</strong>g fund grants forcommunity organisations.8 It thus necessarily tends to exclude the extreme poor who are <strong>in</strong>capable of mak<strong>in</strong>g regular c<strong>as</strong>h sav<strong>in</strong>gs.13

the SHG from banks starts from parity with SHG sav<strong>in</strong>gs and can <strong>in</strong>cre<strong>as</strong>e to 8 times thelevel of SHG sav<strong>in</strong>gs. There are two <strong>in</strong>terl<strong>in</strong>ked parts of the SHG f<strong>in</strong>ancial operations: (i) therotation of its own sav<strong>in</strong>gs and (ii) on-lend<strong>in</strong>g of external funds.The rationale and grow<strong>in</strong>g enthusi<strong>as</strong>m for SHGs among bankers is primarily due to thepossibility of externalisation of the transaction costs of small loans and ensured recoveriesthrough the operation of peer pressure among group members.Loans to SHGs are available at 12 % per annum reduc<strong>in</strong>g balance from banks 9 . The SHGonlends these funds to its members at 18 to 36% with 24% <strong>as</strong> the most commonly reportedrate. The sav<strong>in</strong>gs of the group and the operational profits of f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>in</strong>termediation areavailable for rotation among the members. The SHGs' own capital or sav<strong>in</strong>gs fund is usuallydeployed for lend<strong>in</strong>g to members for short-term and emergency needs. The sav<strong>in</strong>gs fundeffectively also acts <strong>as</strong> the means for servic<strong>in</strong>g the bank loan <strong>in</strong> the event of <strong>in</strong>sufficientrecoveries from group members.Many NGOs and government programmes also provide a revolv<strong>in</strong>g fund grant of Rs. 10,000to Rs. 25,000 to supplement the sav<strong>in</strong>gs of the SHGs 10 . This is often recorded <strong>as</strong> an <strong>in</strong>terestfreeloan to the SHG. Though the objective is to provide supplementary resources to kickstartthe group’s <strong>in</strong>ternal lend<strong>in</strong>g the usual practice among most SHGs is to divide the grantamong members, <strong>in</strong>stead of us<strong>in</strong>g it for credit rotation 11 . Op<strong>in</strong>ion among practitioners nowdoes not generally favour such grants <strong>as</strong> they are not a factor <strong>in</strong> ensur<strong>in</strong>g susta<strong>in</strong>ability ofSHG operations and can <strong>in</strong>stead raise expectations of further grants and handouts..HCSSC and PRADAN are the two study NGOs committed to bank l<strong>in</strong>kage, the ma<strong>in</strong>streammodel adopted by over 2000 NGOs. The other five NGOs have developed models <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>gSHG federations and MFIs and alternative sources of f<strong>in</strong>ancial services to the SHGs 12 . Theseare discussed <strong>in</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g sub-sections. The c<strong>as</strong>e made out by HCCSC and PRADAN forcont<strong>in</strong>ued bank l<strong>in</strong>kage is that given the extensive outreach of the <strong>India</strong>n bank<strong>in</strong>g system, it ismore important and efficient to br<strong>in</strong>g the poor <strong>in</strong>to the fold of the exist<strong>in</strong>g ma<strong>in</strong>streambank<strong>in</strong>g than to promote high cost delivery of f<strong>in</strong>ancial services through (often) unregulated<strong>in</strong>termediaries 13 .3.2 SHGs/Federations of SHGs L<strong>in</strong>ked to Various Types of MFIsDespite the many attractions of the SHG bank l<strong>in</strong>kage model, the considerable reductions <strong>in</strong>transaction costs both for bankers and borrowers and the further possibilities of “graduation”9 While the <strong>in</strong>terest rate cap on loans to SHGs h<strong>as</strong> been removed s<strong>in</strong>ce April 1999, banks cont<strong>in</strong>ue to charge thesame rates <strong>as</strong> under the earlier regulated regime. With a downward movement <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>terest rate regime, no<strong>in</strong>cre<strong>as</strong>e <strong>in</strong> lend<strong>in</strong>g rates of SHGs can be expected <strong>in</strong> the foreseeable future. Indeed, the NABARD ref<strong>in</strong>ance rateof 7.5% to banks is now comparable with rates paid by banks on long-term deposits. It rema<strong>in</strong>s to be seen if theunrestricted or “free” <strong>in</strong>terest rates of banks and MFIs lend<strong>in</strong>g to SHGs with NABARD and SIDBI ref<strong>in</strong>ance areflexible downwards, <strong>as</strong> <strong>in</strong>deed the ref<strong>in</strong>ance rate.10 For example, DWCRA (now SGSY), SAPAP and CASHE projects and several MF programmes of NGOssupported by bilateral donors.11 See, for example, APMAS SHG study f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs for Cuddapah district, December 2001 (www.apm<strong>as</strong>.org).12 HCSSC and PRADAN (<strong>as</strong> also MYRADA) have also promoted federations <strong>in</strong> village clusters but these arenot engaged <strong>in</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>in</strong>termediation.13 These NGOs are work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Bihar and Jharkhand some of the poorest and remote are<strong>as</strong> of the country wherethe local economy is particularly undeveloped. The demand for credit of SHG members is low <strong>as</strong> compared tothat of SHGs <strong>in</strong> other states.14

of <strong>in</strong>dividual borrowers <strong>in</strong>to the banks’ regular lend<strong>in</strong>g programmes, many NGOs andwholesalers favour alternative paths for f<strong>in</strong>ancial service provision for SHG members. There<strong>as</strong>ons for this are varied.NGOs work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the southern states of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh areunhappy with the constra<strong>in</strong>t posed by the sav<strong>in</strong>g requirement on the credit access of SHGs and<strong>in</strong>dividuals. They have organised f<strong>in</strong>ancial federations of SHGs <strong>in</strong> village clusters to facilitate<strong>in</strong>ter-group lend<strong>in</strong>g and larger and more reliable sources of funds than provided under SHGbankl<strong>in</strong>kage. MYRADA (whose federations are non-f<strong>in</strong>ancial), on the other hand, h<strong>as</strong> promoteda not-for-profit company to provide parallel and competitive f<strong>in</strong>ancial services to the exist<strong>in</strong>gbank<strong>in</strong>g channels. Some NGOs have chosen to transform themselves <strong>in</strong>to f<strong>in</strong>ancial<strong>in</strong>termediaries or are <strong>in</strong> the process of sett<strong>in</strong>g up <strong>in</strong>dependent satellite MFIs under the NGOumbrella to act <strong>as</strong> <strong>in</strong>termediaries for SHGs or their federations. While the range ofexperimentation is high, the experience of these different models and evidence of theirreplicability is still very limited. We observe below features of and issues related to thefollow<strong>in</strong>g broad types:• SHGs/SHG clusters/secondary federations l<strong>in</strong>ked to NGO-MFIs• SHGs/SHG federations access<strong>in</strong>g funds from not-for-profit companies and NBFCs• SHG federations borrow<strong>in</strong>g from microf<strong>in</strong>ance wholesalers and banks• Mutually-Aided Cooperative Societies (MACS)We consider each <strong>in</strong> turn.3.2.1 SHGs/SHG Clusters/Secondary Federations L<strong>in</strong>ked to NGO-MFIs(a) NGOs lend<strong>in</strong>g to SHGs/<strong>in</strong>dividualsWhile most NGOs have been content to l<strong>in</strong>k the SHGs directly to banks, some have decidedto <strong>in</strong>volve themselves <strong>in</strong> borrow<strong>in</strong>g and on-lend<strong>in</strong>g funds to SHGs. Two of the NGOscovered <strong>in</strong> this study, NBJK and OUTREACH, are <strong>in</strong> the process of transform<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to MFIsor start<strong>in</strong>g a satellite MFI. NBJK h<strong>as</strong> an impressive range of microf<strong>in</strong>ance andmicroenterprise projects and donor support. It h<strong>as</strong> also promoted an organisation Lok Shaktifor engagement <strong>in</strong> social action. With support from Cordaid it h<strong>as</strong> used the services of ASA,Bangladesh to develop an MFI model. The model <strong>in</strong>volves provid<strong>in</strong>g services to <strong>in</strong>dividualclients (with guarantors from a jo<strong>in</strong>t liability group) <strong>in</strong>stead of loans to SHGs 14 .All over <strong>India</strong>, many NGOs are creat<strong>in</strong>g entities designed to separate the microf<strong>in</strong>anceoperation from their social agenda <strong>in</strong> order that a more professional and bus<strong>in</strong>ess-likeapproach can be adopted 15 . A few features of the NGO <strong>as</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>in</strong>termediary are <strong>as</strong> under:• NGOs can lend to <strong>in</strong>dividuals with or without the <strong>in</strong>volvement of SHGs.• Where SHGs are reta<strong>in</strong>ed, they can either cont<strong>in</strong>ue to borrow and on-lend <strong>as</strong> a groupor be limited to a pure facilitation role, of screen<strong>in</strong>g and recommend<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividualmembers.14 NBJK is, however, also on-lend<strong>in</strong>g to SHGs us<strong>in</strong>g funds provided under CARE-<strong>India</strong>’s CREDIT project <strong>in</strong>Ranchi district.15 This would also permit them to access funds from a range of microf<strong>in</strong>ance wholesalers and donors support<strong>in</strong>gonly professionally managed and susta<strong>in</strong>able NGO-MFIs. However, progress <strong>in</strong> this direction h<strong>as</strong> been slow.15

• In either situation SHGs can cont<strong>in</strong>ue to rotate their own sav<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> a limited f<strong>in</strong>ancial<strong>in</strong>termediation role.• Where loan<strong>in</strong>g is to or through SHGs the NGO does not have access to the group’ssav<strong>in</strong>gs for its operations, s<strong>in</strong>ce these are managed by the SHG itself.• Due to ambiguities <strong>in</strong> the regulatory framework, it is still possible, though notrecommended practice, for NGOs registered <strong>as</strong> non-profit societies, trusts orcompanies to provide sav<strong>in</strong>gs services to their “members”, along the l<strong>in</strong>es of majorBangladesh NGO-MFIs. However, the lead<strong>in</strong>g Grameen replicators (SHARE andCFTS) <strong>in</strong> <strong>India</strong> are registered <strong>as</strong> for-profit NBFCs, which cannot mobilize sav<strong>in</strong>gs.(b) NGOs lend<strong>in</strong>g to SHG clusters/federationsAnother variant of the SHG model is where the SHGs are constituted <strong>in</strong>to f<strong>in</strong>ancialfederations and access supplementary funds from the promot<strong>in</strong>g NGO. OUTREACH h<strong>as</strong>adopted this model through the formation of primary or cluster-level <strong>as</strong>sociations (CLAs).The argument <strong>in</strong> favour of the CLAs is that the SHG is too small a unit to carry out a widerange of f<strong>in</strong>ancial and non-f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>in</strong>termediation. 16 With 10-15 SHGs formed <strong>in</strong>to a cluster,a variety of <strong>in</strong>itiatives can be undertaken to organisationally and f<strong>in</strong>ancially susta<strong>in</strong> thiscommunity-b<strong>as</strong>ed organisation. OUTREACH CLAs undertake bulk purch<strong>as</strong>e of <strong>in</strong>puts, storegra<strong>in</strong>, manage group enterprises, run a crop <strong>in</strong>surance scheme through a risk fund, act <strong>as</strong>agents for <strong>in</strong>surance companies, directly market outputs of member SHGs, promote newSHGs and provide tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, apart from borrow<strong>in</strong>g funds from the NGO for provid<strong>in</strong>g credit tothe SHGs. Appendix 5 illustrates the transactions of an OUTREACH CLA and the l<strong>in</strong>kbetween the SHGs, CLA and the parent NGO. The CLA also is effective <strong>as</strong> the unit to<strong>in</strong>terface with the local bank. Thus, the l<strong>in</strong>k with the bank is shifted from the SHG to theCLA level. The bank’s transaction costs too are much reduced. For example, it is able tomake advances to 200-250 clients through one loan document 17 . CLAs are further federated<strong>in</strong>to project and block level federations.3.2.2 SHGs/SHG Clusters/Federations L<strong>in</strong>ked to Not-for-Profit Companies andNBFCsThe limitation on the quantum of loans available through SHG bank l<strong>in</strong>kage w<strong>as</strong> a majorconcern of various practitioners regard<strong>in</strong>g the model. This h<strong>as</strong> been particularly so <strong>in</strong> thesouthern states where SHG demand for loans is generally higher. Further, the availability offunds from local banks is often determ<strong>in</strong>ed by the degree of <strong>in</strong>terest shown by the bankmanager <strong>in</strong> the bank l<strong>in</strong>kage programme. In the p<strong>as</strong>t there have been many <strong>in</strong>stances of newmanagers fail<strong>in</strong>g to provide loans to SHGs supported earlier by their predecessors. Thiscreates uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty about availability of the bank l<strong>in</strong>kage facility over time 18 .16 A po<strong>in</strong>t of difference between OUTREACH CLAs and those of PRADAN and MYRADA discussed above isthat the latter do not have any f<strong>in</strong>ancial powers. The former, however, shares many of the features of the DHANFoundation cluster <strong>as</strong>sociation discussed <strong>in</strong> section 3.2.3.17 NABARD h<strong>as</strong> piloted a project with OUTREACH <strong>in</strong> which l<strong>in</strong>kage is undertaken by the bank branch with theCLA <strong>in</strong>stead of the SHG.18 The situation, however, is rapidly chang<strong>in</strong>g. Follow<strong>in</strong>g the impressive results over the years and the supportfor it <strong>in</strong> the highest bank<strong>in</strong>g circles – the Reserve Bank of <strong>India</strong> h<strong>as</strong> directed banks to make it their corporatestrategy – SHG-bank l<strong>in</strong>kage is now a showpiece programme. Bank managers generally are com<strong>in</strong>g forward tofacilitate l<strong>in</strong>kage.16