Poverty and Inequality in India: a Reexamination - Princeton University

Poverty and Inequality in India: a Reexamination - Princeton University

Poverty and Inequality in India: a Reexamination - Princeton University

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

eal terms, with updat<strong>in</strong>g on the basis ofapproximate price <strong>in</strong>dexes such as theWholesale Price Index or the CSO’s privateconsumption deflator. The <strong>in</strong>itial ruralurbangap of 15 per cent is anchored <strong>in</strong>1973-74 calorie consumption data, but itis essentially arbitrary s<strong>in</strong>ce the urban <strong>and</strong>rural ‘calorie norms’ themselves (2,100<strong>and</strong> 2,400 calories per person per day,respectively) have a fragile basis. 8 Morerecently, the Plann<strong>in</strong>g Commission hasadopted a modified version of the povertyl<strong>in</strong>es recommended by a 1993 Expert Group[Government of <strong>India</strong> 1993]. The ExpertGroup reta<strong>in</strong>ed the orig<strong>in</strong>al rural <strong>and</strong> urbanl<strong>in</strong>es, but adjusted them for statewisedifferences <strong>in</strong> price levels, separately forurban <strong>and</strong> rural sectors, us<strong>in</strong>g estimates ofstatewise price differences calculated fromNSS data on expenditures <strong>and</strong> quantitiesus<strong>in</strong>g similar methods to those adopted <strong>in</strong>this paper. The Expert Group l<strong>in</strong>es usedthe then best-available <strong>in</strong>formation on pricedifferences across states, both urban <strong>and</strong>rural, but the <strong>in</strong>formation was outdated,especially for the rural sector.Because the statewise adjustments weredone separately for urban <strong>and</strong> rural households,the price differences between theurban <strong>and</strong> rural sectors of each state werederived only implicitly, <strong>and</strong> some are ratherimplausible, particularly the very muchhigher urban than rural l<strong>in</strong>es <strong>in</strong> severalstates. For example, the most recent urbanpoverty l<strong>in</strong>es for Andhra Pradesh <strong>and</strong>Karnataka are around 70 per cent higherthan the correspond<strong>in</strong>g rural l<strong>in</strong>es, with theuncomfortable result that urban poverty ismuch higher than rural poverty <strong>in</strong> thesetwo states (see Table 2 <strong>in</strong> the next section).In Assam, by contrast, the rural povertyl<strong>in</strong>e is actually higher than the urban l<strong>in</strong>e,<strong>and</strong> based on these odd poverty l<strong>in</strong>es, Assamturns out to be one of <strong>India</strong>’s highestpovertystates for rural areas but lowestpovertystates for urban areas. It is hardto accept these <strong>and</strong> other implications ofthe Expert Group poverty l<strong>in</strong>es.There are grounds, of course, for question<strong>in</strong>gwhether it is even possible to derivecomparable rural <strong>and</strong> urban poverty l<strong>in</strong>es.Comparisons of liv<strong>in</strong>g st<strong>and</strong>ards <strong>in</strong> rural<strong>and</strong> urban areas are <strong>in</strong>herently difficult,s<strong>in</strong>ce there are large <strong>in</strong>tersectoral differencesnot only <strong>in</strong> the patterns of consumptionbut also <strong>in</strong> lifestyles, public amenities,epidemiological environments, <strong>and</strong> so on.One way forward is to avoid such comparisonsaltogether, <strong>and</strong> to focus on sectorspecific(rural or urban) poverty estimates.Yet there is a case for attempt<strong>in</strong>g tocompare private consumption levels acrosssectors, bear<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d that this is at besta partial picture of the relevant differences<strong>in</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g st<strong>and</strong>ards. 9 These comparisonscan be made by anchor<strong>in</strong>g poverty estimates<strong>in</strong> a s<strong>in</strong>gle poverty l<strong>in</strong>e, adjusted whereappropriate to take <strong>in</strong>to account rural-urbanprice differences, us<strong>in</strong>g the same methodas that described earlier for adjust<strong>in</strong>gpoverty l<strong>in</strong>es over time <strong>and</strong> between states.Based on this procedure, the urban povertyl<strong>in</strong>e tends be about 15 per cent higher thanthe rural poverty l<strong>in</strong>e, though there arevariations across states. As it turns out, thisrural-urban difference <strong>in</strong> poverty l<strong>in</strong>es isbroadly consistent with the orig<strong>in</strong>almethodology used before the adoption ofthe Expert Group recommendations.To recapitulate, the revised poverty l<strong>in</strong>esused <strong>in</strong> this paper, which are presented <strong>in</strong>full <strong>in</strong> Table 4 of Deaton (2001b), arederived as follows. Our start<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>t isthe official rural all-<strong>India</strong> poverty l<strong>in</strong>e forthe 43rd Round (1987-88): 115.70 rupeesper person per month. 10 Rural povertyl<strong>in</strong>es for each state for the 43rd Round areobta<strong>in</strong>ed by multiply<strong>in</strong>g this base povertyl<strong>in</strong>e by the rural price <strong>in</strong>dexes for each staterelative to all-<strong>India</strong>. The urban povertyl<strong>in</strong>es for the 43rd Round, for each state aswell as for all-<strong>India</strong>, are calculated fromthe rural poverty l<strong>in</strong>es by scal<strong>in</strong>g up by therespective urban relative to rural price<strong>in</strong>dexes. In all cases, we use the relevantTörnqvist price <strong>in</strong>dexes. 11 To move to the50th Round, the orig<strong>in</strong>al all-<strong>India</strong> rurall<strong>in</strong>e, 115.70 rupees, is scaled up by theTörnqvist <strong>in</strong>dex for all-<strong>India</strong> rural for the50th Round relative to the 43rd Round,1.698, to give an all-<strong>India</strong> rural povertyl<strong>in</strong>e for the 50th Round. This number isthen used to generate rural <strong>and</strong> then urbanpoverty l<strong>in</strong>es for each state, follow<strong>in</strong>gexactly the same procedure as for the 43rdRound. F<strong>in</strong>ally, poverty l<strong>in</strong>es for the 55thRound are calculated <strong>in</strong> the same way froman all-<strong>India</strong> rural l<strong>in</strong>e, which is the 50thRound all-<strong>India</strong> rural l<strong>in</strong>e scaled up by thevalue of the Törnqvist <strong>in</strong>dex between thetwo surveys. 12The motivation for the fourth departure(or rather extension) arises from the limitationsof the headcount ratio as an <strong>in</strong>dicatorof poverty. The headcount ratio hasa straightforward <strong>in</strong>terpretation <strong>and</strong> is easyto underst<strong>and</strong>. In that sense it has much‘communication value’. Yet, the HCR hasserious limitations as a poverty <strong>in</strong>dex. Forone th<strong>in</strong>g, it ignores the extent to whichdifferent households fall short of thepoverty l<strong>in</strong>e. This leads to some perverseproperties. For <strong>in</strong>stance, an <strong>in</strong>come transferfrom a very poor person to someonewho is closer to the poverty l<strong>in</strong>e may leadto a decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> the headcount ratio, ifit ‘lifts’ the recipient above the povertyl<strong>in</strong>e. Similarly, if some poor householdsget poorer, this has no effect on theheadcount ratio.A related issue is that changes <strong>in</strong> HCRscan be highly sensitive to the number ofpoor households near the poverty l<strong>in</strong>e (s<strong>in</strong>cechanges <strong>in</strong> the HCR are entirely driven by‘cross<strong>in</strong>gs’ of the poverty l<strong>in</strong>e). If poorhouseholds are heavily ‘bunched’ near thepoverty l<strong>in</strong>e, a small <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> averageper capita <strong>in</strong>come could lead to a mislead<strong>in</strong>glylarge decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> the headcount ratio.This ‘density effect’ has to be kept firmly<strong>in</strong> view <strong>in</strong> the context of comparisons ofpoverty change, <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g questions suchas “has there been more poverty decl<strong>in</strong>e<strong>in</strong> Bihar than <strong>in</strong> Punjab dur<strong>in</strong>g the n<strong>in</strong>eties”,or “has poverty decl<strong>in</strong>ed faster <strong>in</strong> then<strong>in</strong>eties than <strong>in</strong> the eighties?” Often suchquestions are answered by look<strong>in</strong>g at, say,the respective changes (absolute or proportionate)<strong>in</strong> headcount ratios. Thesechanges, however, are difficult to <strong>in</strong>terpret<strong>in</strong> the absence of further <strong>in</strong>formation aboutthe <strong>in</strong>itial density of poor households nearthe poverty l<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> each case.One way forward is to use more sophisticatedpoverty <strong>in</strong>dexes such as the Foster-Greer-Thorbecke (FGT) <strong>in</strong>dexes or the Sen<strong>in</strong>dex. In this paper, we focus on the simplestmember of the FGT class (other thanthe headcount ratio itself), the ‘povertygap<strong>in</strong>dex’. Essentially, the poverty-gap<strong>in</strong>dex (hereafter PGI) is the aggregateshortfall of poor people’s consumptionfrom the poverty l<strong>in</strong>e, suitably normalised.13 The PGI can also be <strong>in</strong>terpreted asthe headcount ratio multiplied by the meanpercentage shortfall of consumption fromthe poverty l<strong>in</strong>e (among the poor). This<strong>in</strong>dex avoids the ma<strong>in</strong> shortcom<strong>in</strong>gs of theheadcount ratio, is relatively simple tocalculate, <strong>and</strong> has a straightforward <strong>in</strong>terpretation.14I.3 Adjusted EstimatesTable 1a presents official <strong>and</strong> adjustedestimates of the all-<strong>India</strong> headcount ratio.In each panel, the first row gives the officialestimates; the second row reta<strong>in</strong>s the officialpoverty l<strong>in</strong>es but adjusts the 1999-2000 estimates for the change <strong>in</strong> questionnairedesign <strong>in</strong> the way described earlier;the third row gives fully-adjusted povertyestimates, which comb<strong>in</strong>e the adjustmentsEconomic <strong>and</strong> Political Weekly September 7, 2002 3733

for questionnaire design <strong>and</strong> for price <strong>in</strong>dexes.Table 1b gives the correspond<strong>in</strong>gpoverty-gap <strong>in</strong>dexes.As the first two rows of each panel<strong>in</strong>dicate, the official estimates are quitemislead<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> their own terms: the 1999-2000 poverty estimates are biased downwardby the changes <strong>in</strong> questionnairedesign. For headcount ratios, the estimatesadjusted for changes <strong>in</strong> questionnairedesign ‘confirm’ about two-thirds of theofficial decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> rural poverty between1993-94 <strong>and</strong> 1999-2000, <strong>and</strong> about 90 percent of the decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> urban poverty. Forpoverty-gap <strong>in</strong>dexes, the correspond<strong>in</strong>gproportions (62 per cent <strong>and</strong> 77 per cent)are lower, especially for the urban sector.The fully-adjusted estimates <strong>in</strong> the lastrow of each panel show somewhat lowerrural poverty estimates <strong>and</strong> much lowerurban poverty estimates for 1999-2000than even the official estimates. Note,however, that because we are recalculat<strong>in</strong>gthe poverty l<strong>in</strong>es back to the 43rd Round,a good deal of the decrease took place <strong>in</strong>the six years prior to 1993-94, not only <strong>in</strong>the six years subsequent to 1993-94. Thefully-adjusted estimates for the headcountratios <strong>and</strong> poverty gap <strong>in</strong>dexes suggest thatpoverty decl<strong>in</strong>e has been fairly evenlyspread between the two sub-periods (before<strong>and</strong> after 1993-94), <strong>in</strong> contrast withthe pattern of ‘acceleration’ <strong>in</strong> the secondsub-period associated with the officialestimates.The rural-urban gaps <strong>in</strong> the povertyestimates are also of <strong>in</strong>terest. Look<strong>in</strong>g firstat the base year (1987-88), the rural-urbangap based on adjusted estimates is muchlarger than that based on official estimates.Indeed, the latter suggest no differencebetween rural <strong>and</strong> urban poverty <strong>in</strong> thatyear. This is hard to reconcile with <strong>in</strong>dependentevidence on liv<strong>in</strong>g conditions <strong>in</strong>rural <strong>and</strong> urban areas, such as a lifeexpectancygap of about seven years <strong>in</strong>favour or urban areas around that time. 15Our low estimate of the urban headcountratio relative to the official estimate (22.5per cent versus 39.1 per cent), <strong>and</strong> similardifferences <strong>in</strong> 1993-94 <strong>and</strong> 1999-2000,come from the fact that we take the ruralpoverty l<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> 1987-88 as our start<strong>in</strong>gpo<strong>in</strong>t, <strong>and</strong> peg the urban poverty l<strong>in</strong>esabout 15 per cent higher than the ruralpoverty l<strong>in</strong>es, <strong>in</strong> contrast to the much largerdifferentials embodied <strong>in</strong> the official l<strong>in</strong>es.Figure 1 shows the new estimates of theheadcount ratios together with the officialestimates go<strong>in</strong>g back to 1973-74. The fullyadjusted figures are lower throughoutHeadcount ratio (per cent)6050403020Figure 1: Official <strong>and</strong> Adjusted Headcounts Ratios1970 1980 1990 2000YearSource: Plann<strong>in</strong>g Commission, Press Releases ( March 11, 1997, <strong>and</strong> February 22, 2001), Deaton (2001a,b), <strong>and</strong> Table 2a of this paper.because we treat the rural poverty l<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>the 43rd Round as our basel<strong>in</strong>e so that,with larger rural-urban gaps <strong>in</strong> the povertyestimates, we estimate lower povertyoverall. If <strong>in</strong>stead, we had taken the urbanpoverty l<strong>in</strong>e as base, the adjusted figureswould have been higher than the officialfigures. From 1987-88 to 1993-94, theadjusted headcount ratio falls more rapidlythan the official headcount; this is becauseour price deflators are ris<strong>in</strong>g less rapidlythan the official ones. From 1993-94, theadjusted figures fall more slowly becausethe effects of the price adjustment are morethan offset by the correction for questionnairedesign. The estimates for the th<strong>in</strong>rounds – which look very different – are<strong>in</strong>cluded to rem<strong>in</strong>d us of the residualuncerta<strong>in</strong>ty about our conclusions, <strong>and</strong>will be discussed further <strong>in</strong> Section IV.3below.I.4 Regional ContrastsState-specific headcount ratios are presented<strong>in</strong> Table 2a. 16 The table has thesame basic structure as Table 1a, exceptthat we jump straight from official to fullyadjustedestimates. The latter suggest thatthe basic pattern of susta<strong>in</strong>ed povertydecl<strong>in</strong>e between 1987-88 <strong>and</strong> 1999-2000,discussed earlier at the all-<strong>India</strong> level, alsoapplies at the level of <strong>in</strong>dividual states <strong>in</strong>most cases. The ma<strong>in</strong> exception is Assam,where poverty has stagnated <strong>in</strong> both rural<strong>and</strong> urban areas. In Orissa, there has beenvery little poverty decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> the secondsub-period, with the result that Orissa nowOfficial countsAdjusted countsTh<strong>in</strong> roundshas the highest level of rural poverty amongall <strong>India</strong>n states, accord<strong>in</strong>g to the adjusted1999-2000 estimates. 17 Reassur<strong>in</strong>gly, the‘anomalies’ noted earlier with respect torural-urban gaps <strong>in</strong> specific states tend todisappear as one moves from official toadjusted estimates.Table 2b shows the correspond<strong>in</strong>g poverty-gap<strong>in</strong>dexes. The general patterns arevery much the same as with headcountratios; <strong>in</strong>deed the PGI series are highlycorrelated with the correspond<strong>in</strong>g HCRseries, with correlation coefficients of 0.98for rural <strong>and</strong> 0.95 for urban. Even the HCR<strong>and</strong> PGI changes between the 50th <strong>and</strong>55th Rounds are highly correlated; thecorrelation coefficient between changes <strong>in</strong>HCR <strong>and</strong> changes <strong>in</strong> PGI is 0.95 for therural sector, <strong>and</strong> 0.96 for the urban sector.Thus, <strong>in</strong> spite of its theoretical superiorityover the headcount ratio, the poverty-gap<strong>in</strong>dex gives us very little additional <strong>in</strong>sight<strong>in</strong> this case.In <strong>in</strong>terpret<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> compar<strong>in</strong>g povertydecl<strong>in</strong>es over time, it is useful to supplementthe poverty <strong>in</strong>dexes with <strong>in</strong>formationon the growth rate of average per capitaconsumption expenditure (hereafterAPCE). State-specific estimates of APCEgrowth between 1993-94 <strong>and</strong> 1999-2000are shown <strong>in</strong> Table 3, where states areranked <strong>in</strong> ascend<strong>in</strong>g order of APCE growthfor rural <strong>and</strong> urban areas comb<strong>in</strong>ed. 18Here, a strik<strong>in</strong>g regional pattern emerges:except for Jammu <strong>and</strong> Kashmir, the lowgrowthstates form one contiguous regionmade up of the eastern states (Assam,Orissa <strong>and</strong> West Bengal), the so-called3734Economic <strong>and</strong> Political Weekly September 7, 2002

Figure 2: ‘Divergence’ of Per Capita Expenditure Across States, 1993-94 to 1999-00Average annual growth (per cent)6420BIORMPUPASKA200 300 400 500 600Source: Authors’ calculations us<strong>in</strong>g unit record data from the 50th <strong>and</strong> 55th Rounds of the National SampleSurvey.AI = All <strong>India</strong>; AP = Andhra Pradesh; AS = Assam; BI = Bihar; DE = Delhi; GU = Gujarat; HA = Haryana;HP = Himachal Pradesh; JK = Jammu <strong>and</strong> Kashmir; KA = Karnataka; KE = Kerala; MA = Maharashtra;MP = Madhya Pradesh; OR = Orissa; PU = Punjab; RA = Rajasthan; TN = Tamil Nadu; UP = Uttar Pradesh;WB = West Bengal.BIMARU states (Bihar, Madhya Pradesh,Rajasthan <strong>and</strong> Uttar Pradesh), <strong>and</strong> AndhraPradesh. The high-growth states, for theirpart, consist of the southern states (exceptAndhra Pradesh), the western states(Gujarat <strong>and</strong> Maharashtra) <strong>and</strong> the northwesternregion (Punjab, Haryana <strong>and</strong>Himachal Pradesh). Further, it is <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>gto note that this pattern is reasonablyconsistent with <strong>in</strong>dependent data on growthrates of per capita ‘state domestic product’(SDP); these are shown <strong>in</strong> the last columnof Table 3. With a couple of exceptionson each side, all the states <strong>in</strong> the ‘lowAPCE growth’ set had comparatively lowrates of per capita SDP between 1993-94<strong>and</strong> 1999-2000 (say below 4 per cent peryear), <strong>and</strong> conversely, all the states <strong>in</strong> the‘high APCE growth’ set had comparativelyhigh annual growth rates of percapita SDP (the correlation coefficientbetween the two series is 0.45). 19This broad regional pattern is a matterof concern, because the low-growth statesalso tend to be states that started off withcomparatively low levels of APCE or percapitaSDP. In other words, there has beena grow<strong>in</strong>g ‘divergence’ of per capita expenditure(<strong>and</strong> also of per capita SDP)AIAPWBTNMAGURAHPHAKEJKPUGeometric mean PCE <strong>in</strong> 1993-94, rupees per headDEacross <strong>India</strong>n states <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties. 20 Thepo<strong>in</strong>t is illustrated <strong>in</strong> Figure 2, which plotsthe average growth <strong>in</strong> APCE for each statebetween 1993-94 <strong>and</strong> 1999-2000 aga<strong>in</strong>stthe geometric mean of APCE <strong>in</strong> 1993-94.It is worth ask<strong>in</strong>g to what extent theseregional patterns, based on APCE data, arecorroborated by regional patterns of povertydecl<strong>in</strong>e. One difficulty here is thatthere is no obvious way of ‘compar<strong>in</strong>g’ theextent of poverty decl<strong>in</strong>e across states. For<strong>in</strong>stance, look<strong>in</strong>g at absolute changes <strong>in</strong>(say) HCRs would seem to give an unfair‘advantage’ to states that start off withhigh levels of poverty, <strong>and</strong> where theretends be a large number of householdsclose to the poverty l<strong>in</strong>e. To illustrate, theabsolute decl<strong>in</strong>e of the rural HCR between1993-94 <strong>and</strong> 1999-2000 was about twiceas large <strong>in</strong> Bihar (7.4 percentage po<strong>in</strong>ts)as <strong>in</strong> Punjab (3.8 po<strong>in</strong>ts), yet over the sameperiod APCE grew by only 6.9 per cent<strong>in</strong> Bihar compared with 20.2 per cent<strong>in</strong> Punjab, with virtually no change <strong>in</strong>distribution <strong>in</strong> either case. 21 The reasonfor this contrast is that Bihar starts off <strong>in</strong>1993-94 with a very high proportion ofhouseholds close to the poverty l<strong>in</strong>e, sothat small <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> APCE can producerelatively large absolute decl<strong>in</strong>es <strong>in</strong> theheadcount ratio.An alternative approach is to look atproportionate changes <strong>in</strong> HCRs or PGIs.These turn out to be highly correlated withthe correspond<strong>in</strong>g growth rates of APCE.The po<strong>in</strong>t is illustrated <strong>in</strong> Figure 3, wherewe plot the proportionate decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> therural headcount ratio <strong>in</strong> each state aga<strong>in</strong>stthe growth rate of APCE <strong>in</strong> rural areas. Thecorrelation coefficient between the twoseries is as high as 0.91. This reflects thefact that poverty reduction is overwhelm<strong>in</strong>glydriven by the growth rate of APCE,rather than by changes <strong>in</strong> distribution – weshall return to this po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>in</strong> Section III.From these observations, it follows that ifwe accept ‘proportionate change <strong>in</strong> HCR’(or PGI) as an <strong>in</strong>dex of poverty reduction,then the broad regional patterns identifiedearlier for the growth rate of APCE alsotend to apply to poverty reduction. Inparticular: (1) most of the western <strong>and</strong>southern states (with the important exceptionof Andhra Pradesh) have done comparativelywell; (2) the eastern region hasachieved very little poverty reductionbetween 1993-94 <strong>and</strong> 1999-2000; <strong>and</strong>(3) there is a strong overall pattern of ‘divergence’(states that were poorer to startwith had lower rates of poverty reduction).This read<strong>in</strong>g of the evidence, however,rema<strong>in</strong>s somewhat tentative, s<strong>in</strong>ce there isno compell<strong>in</strong>g reason to accept the proportionatedecl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> HCR (or PGI) as adef<strong>in</strong>itive measure of poverty decl<strong>in</strong>e.We end this section with a caveat. FromTable 2 <strong>and</strong> Figure 1, it may appear thatthe ‘pace’ of poverty decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>etieshas been fairly rapid. It is important tonote, however, that the associated <strong>in</strong>creases<strong>in</strong> per capita expenditure have been rathermodest <strong>in</strong> most cases. For <strong>in</strong>stance, thedecl<strong>in</strong>e of 6.6 percentage po<strong>in</strong>ts <strong>in</strong> the all-<strong>India</strong> HCR (from 29.2 per cent to 22.7 percent) between 1993-94 <strong>and</strong> 1999-2000 isdriven by an <strong>in</strong>crease of only 10.9 per cent<strong>in</strong> average per capita expenditure – notexactly a spectacular improvement <strong>in</strong>liv<strong>in</strong>g st<strong>and</strong>ards. Similarly, Table 2a suggeststhat Bihar achieved a large step <strong>in</strong>poverty reduction <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties, with therural HCR com<strong>in</strong>g down from 49 per centto 41 per cent. Yet, as Table 3 <strong>in</strong>dicates,average APCE <strong>in</strong> rural Bihar <strong>in</strong>creasedby only 7 per cent between 1993-94 <strong>and</strong>1999-2000.Why are small <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> APCE associatedwith substantial decl<strong>in</strong>es <strong>in</strong> poverty<strong>in</strong>dexes? It is tempt<strong>in</strong>g to answer that thedistribution of consumer expenditureEconomic <strong>and</strong> Political Weekly September 7, 2002 3735

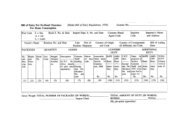

must have improved <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties. Asdiscussed <strong>in</strong> Section III, however, this isnot the case: <strong>in</strong>deed economic <strong>in</strong>equalityhas <strong>in</strong>creased rather than decreased <strong>in</strong> then<strong>in</strong>eties. The correct answer relates to the‘density effect’ mentioned earlier (seeSection I.2): when many poor householdsare close to the poverty l<strong>in</strong>e, modest <strong>in</strong>creases<strong>in</strong> APCE can produce substantialdecl<strong>in</strong>es <strong>in</strong> st<strong>and</strong>ard poverty <strong>in</strong>dexes. Onereason for draw<strong>in</strong>g attention to this is thatthe official poverty estimates have sometimesbeen used to claim that the n<strong>in</strong>etieshave been a period of spectacular achievements<strong>in</strong> poverty reduction. In fact, whenthe relevant adjustments are made, <strong>and</strong>the poverty <strong>in</strong>dexes are read together withthe <strong>in</strong>formation on APCE growth, povertyreduction <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties appears to bemore or less <strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>e with previous rates ofprogress.IIFurther EvidenceII.1 National Accounts StatisticsThere has been much discussion of theconsistency between National SampleSurvey data <strong>and</strong> the ‘national accounts’published by the Central StatisticalOrganisation (CSO). 22 The latter <strong>in</strong>cludeestimates of ‘private f<strong>in</strong>al consumer expenditure’,which is frequently comparedwith NSS estimates of ‘household(Rural)consumption expenditure’. Over time, theCSO estimates have tended to grow fasterthan the NSS estimates, lead<strong>in</strong>g some commentatorsto question the reliability ofNational Sample Survey data.It is important to note that these twonotions of ‘consumer expenditure’ are notTable 3: Growth Rates of APCE <strong>and</strong> Per Capita SDP, 1993-94 to 1999-2000Six-Year Growth of APCE (‘Adjusted’), 1993-94 to 1999-2000 Annual Growth Rate ofRural Urban Comb<strong>in</strong>ed Per Capita SDP,1993-94 to 1999-2000Assam 0.9 8.8 1.7 0.58Orissa 1.4 –0.0 3.3 2.34West Bengal 2.1 11.5 3.3 5.48Jammu <strong>and</strong> Kashmir 5.4 8.0 5.3 2.49Bihar 6.9 4.8 7.1 2.10Madhya Pradesh 6.6 14.1 7.8 2.78Andhra Pradesh 2.8 18.5 8.3 3.57Rajasthan 7.0 15.4 8.6 4.60Uttar Pradesh 8.3 10.1 9.0 2.99<strong>India</strong> 8.7 16.6 10.9 4.36Karnataka 9.5 26.5 14.0 5.82Maharashtra 14.1 16.7 15.9 3.53Gujarat 15.1 20.9 16.8 4.88Himachal Pradesh 16.2 28.5 17.6 5.06Tamil Nadu 15.7 25.1 18.9 5.39Kerala 19.6 18.2 19.6 4.01Punjab 20.2 17.9 19.9 2.74Haryana 31.0 23.0 29.2 3.05Delhi – 30.7 30.7 5.69Note: The states are arranged <strong>in</strong> ascend<strong>in</strong>g order of the growth rate of APCE for rural <strong>and</strong> urban areacomb<strong>in</strong>ed.Sources: For APCE: Authors’ calculations from unit record data for the 50th <strong>and</strong> 55th Rounds of the NationalSample Survey. For SDP: Authors’ calculations based on unpublished data k<strong>in</strong>dly supplied by thePlann<strong>in</strong>g Commission. The figures <strong>in</strong> the last column should be taken as <strong>in</strong>dicative, given thesignificant marg<strong>in</strong> of error <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> SDP estimates.Proportionate decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> rural headcount ratio706050403020100–10Figure 3: HCR Decl<strong>in</strong>es <strong>and</strong> APCE Growth, 1993-94 to 1999-2000ASWBORAP0 5 10 15 20 25 30Source: Tables 2a <strong>and</strong> 3.JKRA UPINDIABI KAMPGUMAHPTNSix-year growth of rural APCEKEPUHAexactly the same, <strong>and</strong> also that there aremajor methodological differences betweenthe two sources. The NSS figures are directestimates of household consumption expenditure.The CSO figures <strong>in</strong>clude severalitems of expenditure that are notcollected <strong>in</strong> the NSS surveys; examples areexpenditures by non-profit entreprises, aswell as imputed rent by owner occupiers<strong>and</strong> ‘f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>in</strong>termediation services<strong>in</strong>directly measured’ (the last item is essentiallythe net <strong>in</strong>terest earned by f<strong>in</strong>ancial<strong>in</strong>termediaries, which is counted asexpenditures on <strong>in</strong>termediation servicesby households). Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Sundaram<strong>and</strong> Tendulkar (2002), who quote a recentcross-validation study by the NationalAccounts Department, the last two itemsaccount for 22 per cent of the difference<strong>in</strong> levels between CSO <strong>and</strong> NSS estimatesof consumer expenditure. Further, the CSOestimates are ‘residual’ figures, obta<strong>in</strong>edafter subtract<strong>in</strong>g other items from thenational product. Leav<strong>in</strong>g aside thesecomparability issues, there is <strong>in</strong>deed a gapbetween the CSO-based <strong>and</strong> NSS-basedgrowth rates of consumer expenditure.Accord<strong>in</strong>g to CSO data, per-capita consumerexpenditure has grown at muchthe same rate as per capita GDP between1993-94 <strong>and</strong> 1999-2000 – about 3.5 percent per year <strong>in</strong> real terms. 23 The correspond<strong>in</strong>gNSS-based estimate associated3736Economic <strong>and</strong> Political Weekly September 7, 2002

n<strong>in</strong>eties. 28 Thus, real agricultural wageswere grow<strong>in</strong>g considerably faster <strong>in</strong> theeighties than <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties. But even thereduced growth rate of agricultural wages<strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties, at 2.5 per cent per year,po<strong>in</strong>ts to significant growth of per capitaexpenditure among the poorer sections ofthe population <strong>and</strong> re<strong>in</strong>forces our earlierf<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs on poverty reduction. In fact, thisreduced growth rate is a little higher thanthe growth rate of average per capitaexpenditure (1.5 per cent per year) thatsusta<strong>in</strong>s our estimated decl<strong>in</strong>es of ruralheadcount ratios <strong>and</strong> headcount <strong>in</strong>dexesbetween 1993-94 <strong>and</strong> 1999-2000.The data on real wages also providesome <strong>in</strong>dependent corroboration of thestate-specific patterns of poverty decl<strong>in</strong>e.This is illustrated <strong>in</strong> Figure 5, where weplot state-specific estimates of the growthrate of real agricultural wages <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>etiesaga<strong>in</strong>st the estimated proportionatedecl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> the headcount ratio (a very similarpattern applies to the poverty-gap <strong>in</strong>dex).Here the two ma<strong>in</strong> outliers are Punjab <strong>and</strong>Haryana, where the headcount ratio hasdecl<strong>in</strong>ed sharply without a correspond<strong>in</strong>glysharp <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> real wages (<strong>in</strong>deedwithout any such <strong>in</strong>crease, <strong>in</strong> the case ofPunjab). Leav<strong>in</strong>g out these two outliers,the association between the two series isremarkably close (with a correlation coefficientof 0.88).An <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g sidelight emerg<strong>in</strong>g fromFigure 5 is that a healthy growth of realagricultural wages appear to be a ‘sufficient’condition for substantial povertydecl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> rural areas: all the states wherereal wages have grown at more than, say,2.5 per cent per year <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties haveexperienced a comparatively sharp reductionof the rural headcount ratio. Conversely,<strong>in</strong> states with low rates of reductionof the headcount ratio (say, 15 per centor less over six years), real wages have<strong>in</strong>variably grown at less than 2 per centper year. This applies <strong>in</strong> particular to theentire eastern region (Assam, Orissa, WestBengal <strong>and</strong> Bihar) <strong>and</strong> also to AndhraPradesh <strong>and</strong> Madhya Pradesh.Independent evidence on the growth ratesof real wages has recently been presentedby K Sundaram (2001a, 2001b), based onthe ‘employment-unemployment surveys’(EUS) of the National Sample Survey for1993-94 <strong>and</strong> 1999-2000. For the presentpurpose, these surveys are comparable.Sundaram estimates that the real earn<strong>in</strong>gsof agricultural labourers have grown atabout 2.5 per cent per year between 1993-94<strong>and</strong> 1999-2000. These are tentativeRural headcount ratio (adjusted)50403020100Figure 4: Agricultural Wages <strong>and</strong> Rural <strong>Poverty</strong>, 1999-2000ORKA0 2 3 4 5 6 7 8Real agricultural wageSource: Drèze <strong>and</strong> Sen (2002), Statistical Appendix, Table A 3, <strong>and</strong> Table 2a of this paper. The “realagricultural wage” is a three-year average end<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> 1999-2000.estimates, based as they are on data for twoyears only. Yet it is reassur<strong>in</strong>g to f<strong>in</strong>d thatthey are consistent with the AWI-basedestimates.II.3 The ‘Employment-Unemployment Surveys’The National Sample Survey’s 1993-94<strong>and</strong> 1999-2000 employment-unemploymentsurveys (EUS) also <strong>in</strong>clude consumerexpenditure data. These can be used forfurther scrut<strong>in</strong>y of poverty trends. Thistask has been undertaken <strong>in</strong> a recent paperby Sundaram <strong>and</strong> Tendulkar (2002). Theynote that the consumption survey <strong>in</strong> the1999-2000 EUS uses the traditional 30-day report<strong>in</strong>g period, but differs from thest<strong>and</strong>ard questionnaire by only ask<strong>in</strong>g anabbreviated set of questions. However, theauthors f<strong>in</strong>d that, <strong>in</strong> those cases where thequestions have comparable coverage, themeans from the EUS, us<strong>in</strong>g the traditional30-day report<strong>in</strong>g period, are typically closeto those from the 30-day questionnaire <strong>in</strong>the ma<strong>in</strong> consumption survey. Based onthis correspondence, they argue that the30-day questions <strong>in</strong> the ma<strong>in</strong> 1999-2000survey were not much distorted by theseven-day questions that were asked alongsidethem. In this version of events, themajor source of <strong>in</strong>comparability betweenthe 55th <strong>and</strong> 50th Rounds is not the contam<strong>in</strong>ationof the 30-day questions, butrather the revised treatment of the lowBIMPUPASAPMAINDIATNWBGURAPUHAKEfrequency items, for which the report<strong>in</strong>gperiod was 30 days <strong>in</strong> the 50th Round <strong>and</strong>365 days <strong>in</strong> the 55th Round. As we havealready noted, the 365-day report<strong>in</strong>g periodfor these items pulls up the lower tailof the consumption distribution, <strong>and</strong> thusbiases down the headcount ratio comparedwith earlier methods. However, Sundaram<strong>and</strong> Tendulkar note that the 50th Roundconta<strong>in</strong>ed both 30-day <strong>and</strong> 365-day report<strong>in</strong>gperiods for the low frequency items.Hence, by recalculat<strong>in</strong>g the 50th Roundheadcounts us<strong>in</strong>g the 365-day responses,they can put the 50th <strong>and</strong> 55th Rounds ona roughly comparable basis. When they dothis, they f<strong>in</strong>d that, <strong>in</strong> both rural <strong>and</strong> urbansectors, they can confirm a little more thanthree-quarters of the official decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> theheadcount ratios between the two rounds[Sundaram <strong>and</strong> Tendulkar 2002:Table III.8]. These calculations are notidentical to our first-step adjustments (seeTable 1a), but they are close enough to<strong>in</strong>spire some confidence that both sets ofresults are <strong>in</strong> the right range.To sum up, the all-<strong>India</strong> poverty <strong>in</strong>dexespresented earlier <strong>in</strong> this paper are broadlyconsistent with <strong>in</strong>dependent evidence fromthe national accounts statistics <strong>and</strong> theemployment-unemployment surveys, aswell as with related <strong>in</strong>formation on agriculturalwages. There is also some congruencebetween the <strong>in</strong>ter-state contrastsemerg<strong>in</strong>g from NSS data <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>dependent<strong>in</strong>formation on state-specific growth rates3738Economic <strong>and</strong> Political Weekly September 7, 2002

Proportionate decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> rural HCR806040200Source: See Figure 4.Figure 5: Wage Growth <strong>and</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> Decl<strong>in</strong>e, 1993-94 to 1999-2000PU–4 –2 0 2 4 6 8 10Growth rate of real agricultural wageof ‘state domestic product’ <strong>and</strong> real agriculturalwages. The comb<strong>in</strong>ed evidencefrom these different sources is fairly strong,even though each <strong>in</strong>dividual source hassignificant limitations.IIIEconomic <strong>Inequality</strong> <strong>in</strong> theN<strong>in</strong>etiesIII.1 Growth, <strong>Poverty</strong><strong>and</strong> <strong>Inequality</strong>MABIMPWBAPORASIt is possible to th<strong>in</strong>k about povertydecl<strong>in</strong>e, as captured by st<strong>and</strong>ard poverty<strong>in</strong>dexes, <strong>in</strong> terms of two dist<strong>in</strong>ct components:a growth component <strong>and</strong> a distributioncomponent. The growth componentreflects the <strong>in</strong>crease of average percapita expenditure. The distribution componentcaptures any change that may takeplace <strong>in</strong> the distribution of per capita expenditureover households.This decomposition exercise is pursued<strong>in</strong> Table 4, with reference to the headcountratio (very similar results apply to thepoverty-gap <strong>in</strong>dex). The first column repeatsthe headcount ratio for 1993-94from Table 2. The second column (labelled‘derivative with respect to growth’) showsour estimate of the percentage-po<strong>in</strong>t reduction<strong>in</strong> HCR associated with a distribution-neutral,1 per cent <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> APCE<strong>in</strong> the relevant state. To illustrate, <strong>in</strong> ruralAndhra Pradesh a 1 per cent <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong>APCE <strong>in</strong> 1993-94, with no change <strong>in</strong>HAUPINDIARATNKAGUKEdistribution, would have led to a decl<strong>in</strong>eof 0.9 percentage po<strong>in</strong>ts <strong>in</strong> the ruralheadcount ratio. 29 This derivative dependspositively on the fraction of people whoare at or near the poverty l<strong>in</strong>e, which istypically larger <strong>in</strong> the poorer states. Thefigures <strong>in</strong> column 2 vary from –1.27 <strong>in</strong>rural Assam to –0.15 <strong>in</strong> urban Jammu <strong>and</strong>Kashmir. Column 3 reproduces the totalpercentage growth between 1993-94 <strong>and</strong>1999-2000 from Table 3.If we multiply the second column (thederivative with respect to growth) by thethird column (the amount of growth), weget an estimate of the amount of povertyreduction that we would expect from growthalone, <strong>in</strong> the absence of any change <strong>in</strong> theshape of the distribution. This is an approximation,because the derivative is likelyto change as the headcount ratio falls. Incolumn 4, we report a more precise calculation:an estimate of what the headcountratio would have been <strong>in</strong> 1999-2000 if thedistributions of consumption <strong>in</strong> each statewere identical to those <strong>in</strong> 1993-94, but hadbeen shifted upwards by the amount ofgrowth <strong>in</strong> real per capita expenditure thatactually took place. This can be readilycalculated by reduc<strong>in</strong>g the 1993-94 povertyl<strong>in</strong>es by the amount of growth, <strong>and</strong>re-estimat<strong>in</strong>g the headcount ratios fromthese adjusted l<strong>in</strong>es <strong>and</strong> the 1993-94 expendituredata. These hypothetical changescan then be compared with the actualreductions <strong>in</strong> the headcount ratios, shown<strong>in</strong> the f<strong>in</strong>al column. The differencebetween these last two columns is thechange <strong>in</strong> the headcount ratio that is attributableto changes <strong>in</strong> the shape of theconsumption distribution.It is important to note that the last twocolumns are highly correlated. The correlationcoefficients across the states are0.97 (rural) <strong>and</strong> 0.93 (urban), so that growthalone can predict much of the cross-statepattern of reduction <strong>in</strong> HCRs. Nevertheless,the estimates are far from identical. Inparticular, the all-<strong>India</strong> calculations showthat ‘growth alone’ would have reduced thepoverty rate by more than actually happened,imply<strong>in</strong>g that there was an <strong>in</strong>crease<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>equality that offset some of the effectsof growth, or put differently, that APCEgrowth among the poor was less than theaverage. These <strong>in</strong>equality effects varysomewhat from state to state <strong>and</strong> are muchweaker <strong>in</strong> rural than <strong>in</strong> urban areas. Inurban <strong>India</strong>, <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>equality moderatedthe decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> the headcount ratio <strong>in</strong>all states except Delhi, Maharashtra, <strong>and</strong>Jammu <strong>and</strong> Kashmir. In some cases, suchas urban Kerala <strong>and</strong> Madhya Pradesh, the‘moderat<strong>in</strong>g effect’ is pronounced, withactual rates of reduction only a little over halfthose predicted by the growth <strong>in</strong> the mean.For the urban sector as a whole (the lastrow of the table), the actual decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> theHCR is one <strong>and</strong> a half po<strong>in</strong>ts lower (5.9versus 7.4 per cent) than would have beenthe case had growth been equally distributedwith<strong>in</strong> each state. This estimate, whichis the population-weighted average of thecorrespond<strong>in</strong>g numbers for each state,calculates what would have happened ifeach household <strong>in</strong> each state had experiencedthe average growth for that state. Analternative, <strong>and</strong> equally <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g, counterfactualis what would have happened if,between 1993-94 <strong>and</strong> 1999-2000, eachhousehold <strong>in</strong> the country had experiencedthe countrywide growth rate of 10.9 percent. Such a calculation yields an all-<strong>India</strong>HCR of 21.4 per cent (for rural <strong>and</strong> urbanareas comb<strong>in</strong>ed), compared with an actualall-<strong>India</strong> HCR of 22.7 per cent based onthe 55th Round. In other words, the all-<strong>India</strong> HCR <strong>in</strong> 1999-2000 was 1.3 percentagepo<strong>in</strong>ts higher than it would have been(with the same growth rate of APCE) <strong>in</strong>the absence of any <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>equality.III.2 Aspects of Ris<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Inequality</strong>Three aspects of ris<strong>in</strong>g economic <strong>in</strong>equality<strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties have come up sofar <strong>in</strong> our story. First, we found strongevidence of ‘divergence’ <strong>in</strong> per capitaEconomic <strong>and</strong> Political Weekly September 7, 2002 3739

consumption across states. Second, ourestimates of the growth rates of per capitaexpenditure between 1993-94 <strong>and</strong> 1999-2000 (Table 3) po<strong>in</strong>t to a significant <strong>in</strong>crease<strong>in</strong> rural-urban <strong>in</strong>equalities at the all-<strong>India</strong> level, <strong>and</strong> also <strong>in</strong> most <strong>in</strong>dividualstates. Third, the decomposition exercise<strong>in</strong> the preced<strong>in</strong>g section shows that ris<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>equality with<strong>in</strong> states, particularly <strong>in</strong> theurban sector, has moderated the effects ofgrowth on poverty reduction.Table 5 provides more systematic evidenceon recent changes <strong>in</strong> consumption<strong>in</strong>equality with<strong>in</strong> each sector of each stateus<strong>in</strong>g two different measures of <strong>in</strong>equality.We show the logarithm of the differenceof the arithmetic <strong>and</strong> geometric means(approximately the fraction by which thearithmetic mean exceeds the geometricmean), as well as the variance of thelogarithm of per capita expenditure.The table shows that the correction forquestionnaire design is critical for underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>gwhat has been happen<strong>in</strong>g. (Notethat the correction for prices has no effectwith<strong>in</strong> sectors <strong>and</strong> states.) The direct useof the unit record data <strong>in</strong> the 55th Round,with no adjustment, shows a substantialreduction <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>equality with<strong>in</strong> the ruralsectors of most states, with little or no<strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> the urban sectors. With thecorrection, we see that with<strong>in</strong>-state rural<strong>in</strong>equality has not fallen, <strong>and</strong> that therehave been marked <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> with<strong>in</strong>-stateurban <strong>in</strong>equality. We suspect that the ma<strong>in</strong>reason why the unadjusted data are somislead<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> this context is the changefrom 30 to 365 days <strong>in</strong> the report<strong>in</strong>g periodfor the low frequency items (durable goods,cloth<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> footwear, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutionalmedical <strong>and</strong> educational expenditures). Thelonger report<strong>in</strong>g period actually reducesthe mean expenditures on those items, butbecause a much larger fraction of peoplereport someth<strong>in</strong>g over the longer report<strong>in</strong>gperiod, the bottom tail of the consumptiondistribution is pulled up, <strong>and</strong> both <strong>in</strong>equality<strong>and</strong> poverty are reduced. Whether 365-days are a better or worse report<strong>in</strong>g periodthan 30-days could be argued either way,but the ma<strong>in</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t here is that the 55th <strong>and</strong>50th Rounds are not comparable, <strong>and</strong> thatthe former artificially shows too little<strong>in</strong>equality compared with the latter. Oncethe corrections are made, we see that, <strong>in</strong>addition to <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>equality betweenstates, there has been a marked <strong>in</strong>crease<strong>in</strong> consumption <strong>in</strong>equality with<strong>in</strong> theurban sector of nearly all states.Two further pieces of evidence areworth mention<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> this context. First,our f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs on ris<strong>in</strong>g economic <strong>in</strong>equalitywith<strong>in</strong> the urban sector are consistent withrecent work by Banerjee <strong>and</strong> Piketty (2001),who use <strong>in</strong>come tax records to documentvery large <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>come among thevery highest <strong>in</strong>come earners. They showthat, <strong>in</strong> the 1990s, real <strong>in</strong>comes among thetop one per cent of <strong>in</strong>come earners <strong>in</strong>creasedby a half <strong>in</strong> real terms, while thoseof the top 1 per cent of 1 per cent <strong>in</strong>creasedby a factor of three <strong>in</strong> real terms.Second, it is <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g to compare thegrowth rate of real wages for agriculturallabourers with that of public sector salaries.As we saw earlier, real agriculturalwages have grown at 2.5 per cent or so<strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties. Public sector salaries, fortheir part, have grown at almost 5 per centper year dur<strong>in</strong>g the same period. 30 Giventhat public-sector employees tend to bemuch better off than agricultural labourers,this can be taken as an <strong>in</strong>stance of ris<strong>in</strong>geconomic disparities between differentTable 5: <strong>Inequality</strong> Measuresoccupation groups. S<strong>in</strong>ce agriculturallabourers <strong>and</strong> public sector employeestypically reside <strong>in</strong> rural <strong>and</strong> urban areas,respectively, this f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g may just beanother side of the co<strong>in</strong> of ris<strong>in</strong>g ruralurb<strong>and</strong>isparities. Even then, it strengthensthe evidence presented earlier onaspects of ris<strong>in</strong>g economic <strong>in</strong>equality <strong>in</strong>the n<strong>in</strong>eties.To sum up, except for the absence ofclear evidence of ris<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>tra-rural <strong>in</strong>equalitywith<strong>in</strong> states, we f<strong>in</strong>d strong <strong>in</strong>dicationsof a pervasive <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> economic<strong>in</strong>equality <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties. This isa new development <strong>in</strong> the <strong>India</strong>n economy:until 1993-94, the all-<strong>India</strong> G<strong>in</strong>i coefficientsof per capita consumer expenditure<strong>in</strong> rural <strong>and</strong> urban areas were fairly stable. 31Further, it is worth not<strong>in</strong>g that the rate of<strong>in</strong>crease of economic <strong>in</strong>equality <strong>in</strong> then<strong>in</strong>eties is far from negligible. For <strong>in</strong>stance,the compound<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>in</strong>ter-state‘divergence’ <strong>and</strong> ris<strong>in</strong>g rural-urbanlogAM¥logGM aVariance of Logs50th Round 55th Round 55th Round 50th Round 55th Round 55th RoundAdjustedAdjustedAndhra PradeshAssamBiharGujaratHaryanaHimachal PradeshJammu <strong>and</strong> KashmirKarnatakaKeralaMadhya PradeshMaharashtraOrissaPunjabRajasthanTamil NaduUttar PradeshWest BengalAll-<strong>India</strong> Rural0.140.050.080.100.160.130.100.120.150.130.160.100.130.120.160.130.110.140.090.070.070.090.100.100.060.100.140.100.110.100.100.070.140.100.090.110.130.060.080.110.230.140.070.120.160.120.160.120.140.100.150.120.080.140.240.100.160.170.280.220.160.210.260.220.270.180.220.200.270.230.170.230.170.130.130.180.190.170.120.180.240.180.200.180.190.140.230.180.150.210.220.110.160.180.310.240.140.220.270.220.280.210.240.180.240.210.150.24Andhra PradeshAssamBiharGujaratHaryanaHimachal PradeshJammu <strong>and</strong> KashmirKarnatakaKeralaMadhya PradeshMaharashtraOrissaPunjabRajasthanTamil NaduUttar PradeshWest BengalDelhi0.170.130.150.140.130.380.130.160.200.180.210.150.130.140.210.170.190.160.160.170.140.140.160.090.180.170.170.210.140.140.130.270.180.200.170.140.170.140.150.420.120.170.220.180.210.160.140.140.200.190.190.300.250.270.250.240.370.240.310.310.290.400.290.230.250.390.310.340.290.300.300.250.270.290.160.320.320.290.360.260.250.230.340.310.310.330.270.300.260.280.400.210.340.370.330.400.290.250.260.350.340.350.29 0.21 0.30 0.43 0.39 0.46All-<strong>India</strong> Urban 0.19 0.20 0.21 0.34 0.34 0.37All-<strong>India</strong> 0.17 0.18 0.19 0.29 0.29 0.32Note: a AM is the arithmetic mean <strong>and</strong> GM is the geometric mean: the difference <strong>in</strong> their logarithms is themean relative deviation, a measure of <strong>in</strong>equality.3740Economic <strong>and</strong> Political Weekly September 7, 2002

250.0200.0150.0100.050.0Figure 6: Food Intake for Different Per Capita Income Groups, as a Proportion(Per Cent) of Average Intake (1996-97)0.0Cereals <strong>and</strong> millets Fats <strong>and</strong> oils Sugar <strong>and</strong> Jaggery Milk <strong>and</strong> milk productsPer capita <strong>in</strong>come groups (Rs/cap/month) less than 90 90-150150-300 300-600 more than 600Source: Calculated from National Nutrition Monitor<strong>in</strong>g Bureau (1999), Table 6.9. The data relate to ruralareas of eight sample states.disparities produces very sharp contrasts<strong>in</strong> APCE growth between the rural sectorsof the slow-grow<strong>in</strong>g states <strong>and</strong> the urbansectors of the fast-grow<strong>in</strong>g states (Table 3).This is further compounded by the accentuationof <strong>in</strong>tra-urban <strong>in</strong>equality, which isitself quite substantial, bear<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>dthat the change is measured over a shortperiod of six years (Table 5).It might be argued that a temporary<strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> economic <strong>in</strong>equality is to beexpected <strong>in</strong> a liberalis<strong>in</strong>g economy, <strong>and</strong>that this trend is likely to be short-lived.Proponents of the ‘Kuznets curve’ mayeven expect it to be reversed <strong>in</strong> due course.However, Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s experience of sharp <strong>and</strong>susta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> economic <strong>in</strong>equalityover a period of more than 20 years, aftermarket-oriented economic reforms were<strong>in</strong>itiated <strong>in</strong> the late 1970s, does not <strong>in</strong>spiremuch confidence <strong>in</strong> this prognosis. 32 It is,<strong>in</strong> fact, an important po<strong>in</strong>ter to the possibilityof further accentuation of economicdisparities <strong>in</strong> <strong>India</strong> <strong>in</strong> the near future.IVQualifications <strong>and</strong> ConcernsIV.1 Food ConsumptionThere have been major changes <strong>in</strong> <strong>India</strong>’sfood economy <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties. The eightieswere a period of healthy growth <strong>in</strong> agriculturaloutput, food production, <strong>and</strong> realagricultural wages. Dur<strong>in</strong>g the n<strong>in</strong>eties,however, productivity <strong>in</strong>creases sloweddown <strong>in</strong> many states. The quantity <strong>in</strong>dexof agricultural production grew at a lame2 per cent per year or so. The growth ofreal agricultural wages slowed down considerably.And cereal production barelykept pace with population growth. 33The virtual stagnation of per capita cerealproduction <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties has been accompaniedby a gradual switch from net importsto net exports, <strong>and</strong> also by a massiveaccumulation of public stocks. Correspond<strong>in</strong>gly,there has been no <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> estimatedper capita ‘net availability’ of cereals(Table 6). If anyth<strong>in</strong>g, net availabilitydecl<strong>in</strong>ed a little, from a peak of about 450grams per person per day <strong>in</strong> 1990 to 420grams or so at the end of the n<strong>in</strong>eties. Thisis consistent with <strong>in</strong>dependent evidence,from National Sample Survey data, of adecl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> per capita cereal consumption<strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties. Between 1993-94 <strong>and</strong> 1999-2000, for <strong>in</strong>stance, average cereal consumptionper capita decl<strong>in</strong>ed from 13.5 kgper month to 12.7 kg per month <strong>in</strong> ruralareas, <strong>and</strong> from 10.6 to 10.4 kg per month<strong>in</strong> urban areas. 34 This comparison isbased on the ‘uncorrected’ 55th Rounddata, <strong>and</strong> the ‘true’ decl<strong>in</strong>e may be largerstill, given the changes <strong>in</strong> questionnairedesign (Section I.1).The reduction of cereal consumption <strong>in</strong>the n<strong>in</strong>eties may seem <strong>in</strong>consistent withthe notion that poverty has decl<strong>in</strong>ed dur<strong>in</strong>gthe same period. Indeed, this pattern hasbeen widely <strong>in</strong>voked as evidence of ‘impoverishment’<strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties. If cereal consumptionis decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, how can povertybe decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g?It is worth not<strong>in</strong>g, however, that thedecl<strong>in</strong>e of cereal consumption is not new.A similar decl<strong>in</strong>e took place (accord<strong>in</strong>g toNational Sample Survey data) dur<strong>in</strong>g theseventies <strong>and</strong> eighties, when poverty wascerta<strong>in</strong>ly decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. Hanchate <strong>and</strong> Dyson’s(2000) recent comparison of rural foodconsumption patterns <strong>in</strong> 1973-74 <strong>and</strong>1993-94 sheds some useful light on thismatter. As the authors show, dur<strong>in</strong>g thisperiod per capita cereal consumption <strong>in</strong>rural areas decl<strong>in</strong>ed quite sharply on average(from 15.8 to 13.6 kgs per personper month), but rose among the pooresthouseholds. The decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> the average isdriven by reduced consumption among thehigher expenditure groups. 35The average decl<strong>in</strong>e is unlikely to bedriven by changes <strong>in</strong> relative prices;<strong>in</strong>deed, there has been little change <strong>in</strong> foodprices, relative to other prices, <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>terven<strong>in</strong>gperiod. Instead, this pattern appearsto reflect a substitution away fromcereals to other food items as <strong>in</strong>comes rise(at least beyond a certa<strong>in</strong> threshold). Theconsumption of ‘superior’ food items suchas vegetables, milk, fruit, fish <strong>and</strong> meat didrise quite sharply over the same period,across all expenditure groups. Seen <strong>in</strong> thislight, the decl<strong>in</strong>e of average cereal consumptionmay not be a matter of concernper se. Indeed, average cereal consumptionis <strong>in</strong>versely related to per capita <strong>in</strong>comeacross countries (e g, it is lower <strong>in</strong>Ch<strong>in</strong>a than <strong>in</strong> <strong>India</strong>, <strong>and</strong> even lower <strong>in</strong> theUnited States), <strong>and</strong> the same applies acrossstates with<strong>in</strong> <strong>India</strong> (e g, cereal consumptionis higher <strong>in</strong> Bihar or Orissa than <strong>in</strong>Punjab or Haryana).Food <strong>in</strong>take data collected by the NationalNutrition Monitor<strong>in</strong>g Bureau(NNMB) shed further light on this issue.Aside from detailed <strong>in</strong>formation on food<strong>in</strong>take, the NNMB surveys <strong>in</strong>clude roughestimates of household <strong>in</strong>comes. These areused <strong>in</strong> Figure 6 to display the relationbetween per-capita <strong>in</strong>come <strong>and</strong> food <strong>in</strong>take,for different types of food. The substitutionfrom cereals towards other fooditems with ris<strong>in</strong>g per-capita <strong>in</strong>come emergesquite clearly. 36 This pattern, if confirmed,would fit quite well with the data on changeover time. 37 It also implies that the decl<strong>in</strong>eof average cereal consumption <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>etiesis not <strong>in</strong>consistent with our earlierf<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs on poverty decl<strong>in</strong>e. 38IV.2 Localised Impoverishment<strong>and</strong> Hidden CostsThe overall decl<strong>in</strong>e of poverty <strong>in</strong> then<strong>in</strong>eties does not rule out the possibilityof impoverishment among specific regionsor social groups. That possibility, of course,is not new, but it is worth ask<strong>in</strong>g whetherEconomic <strong>and</strong> Political Weekly September 7, 2002 3741

6.05.04.03.02.01.00.0Figure 7:Progress of Selected Social Indicators <strong>in</strong> the 1980s <strong>and</strong> 1990s(Per Cent Per Year)5.52.52.9Increase of real Decl<strong>in</strong>e of <strong>in</strong>fant Decl<strong>in</strong>e of total Decl<strong>in</strong>e ofagricultural wages mortality rate fertility rate illiteracy rateSource: Drèze <strong>and</strong> Sen (2002), chapter 9.1.5its scope has exp<strong>and</strong>ed dur<strong>in</strong>g the lastdecade. As the economy gives greater roomto market forces, uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>equalityoften <strong>in</strong>crease, possibly lead<strong>in</strong>g toenhanced economic <strong>in</strong>security among thosewho are not <strong>in</strong> a position to benefit fromthe new opportunities, or whose livelihoodsare threatened by the changes <strong>in</strong> theeconomy. The <strong>in</strong>crease of economic <strong>in</strong>equality<strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties, noted earlier,suggests that tendencies of this k<strong>in</strong>d maywell be at work <strong>in</strong> <strong>India</strong> today. Adversetrends <strong>in</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g st<strong>and</strong>ards could take severaldist<strong>in</strong>ct forms, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g: (1) impoverishmentamong specific regions or socialgroups, (2) heightened uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty <strong>in</strong>general, <strong>and</strong> (3) grow<strong>in</strong>g ‘hidden costs’ ofeconomic development.In connection with the first po<strong>in</strong>t, wehave already noted that some of the poorerstates, notably Orissa <strong>and</strong> Assam, have notfared well at all <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties. It is quitepossible that the poorer regions with<strong>in</strong>these states have done even worse, to thepo<strong>in</strong>t of absolute impoverishment forsubstantial sections of the population. Inthe case of Orissa, there is some <strong>in</strong>dependentevidence of localised impoverishment<strong>in</strong> the poorer districts, due <strong>in</strong>ter alia to thedestruction of the local environmental base<strong>and</strong> to the dismal failure of state-sponsoreddevelopment programmes [Drèze2001]. 39Similarly, the overall improvement ofliv<strong>in</strong>g st<strong>and</strong>ards may hide <strong>in</strong>stances ofimpoverishment among specific occupationgroups. The n<strong>in</strong>eties have been a periodof rapid structural change <strong>in</strong> the <strong>India</strong>neconomy, lead<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> some cases to1.71.81.52.81980s1990sconsiderable disruption of earlier livelihoodpatterns. Examples <strong>in</strong>clude a deeprecession <strong>in</strong> the powerloom sector, a seriouscrisis <strong>in</strong> the edible oil <strong>in</strong>dustry afterimport tariffs were slashed, periodic wavesof bankruptcy among cotton growers, thedisplacement of traditional fish<strong>in</strong>g bycommercial shrimp farms, <strong>and</strong> a numberof sectoral crises associated with the abruptlift<strong>in</strong>g of quantitative restrictions on imports<strong>in</strong> mid-2001. 40 The destruction oflocal environmental resources is anothercommon cause of disrupted livelihoods <strong>in</strong>many areas.A related issue is the possibility of ‘hiddenhardships’ associated with recent patternsof economic development. To illustrate,there is much evidence that, <strong>in</strong> many ofthe poorer regions of <strong>India</strong>, further impoverishmenthas been avoided ma<strong>in</strong>ly throughseasonal labour migration. 41 The latteroften entails significant social costs thatTable 6: Cereal Availability <strong>in</strong> the N<strong>in</strong>eties(Grams per person per day)are poorly captured, if at all, <strong>in</strong> st<strong>and</strong>ardpoverty <strong>in</strong>dexes or for that matter <strong>in</strong> theother social <strong>in</strong>dicators exam<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> thispaper. Examples of such costs <strong>in</strong>cludeirregular school attendance, the spread ofHIV/AIDS, the disruption of family life,<strong>and</strong> ris<strong>in</strong>g urban congestion. 42 Similarly,<strong>in</strong>voluntary displacement of persons affectedby large development projects suchas dams <strong>and</strong> m<strong>in</strong>es tends to have enormoushuman costs. These, aga<strong>in</strong>, are largelyhidden from view <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>come-based analysesof poverty. In fact, the <strong>in</strong>comes ofdisplaced persons often rise (with ‘cashcompensation’) even as their lives are be<strong>in</strong>gshattered. 43 The ‘<strong>in</strong>formalisation’ of labourmarkets is another example of economicchange with substantial hidden costs (e g,longer work<strong>in</strong>g hours, higher <strong>in</strong>security,lower status, <strong>and</strong> deteriorat<strong>in</strong>g work conditions).44 These issues are not new, butit is important to acknowledge the possibilitythat the hidden costs of economicgrowth have <strong>in</strong>tensified <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties.This acknowledgement helps to reconcilethe survey-based evidence reviewedearlier with widespread media reports, <strong>in</strong>recent years, of sectoral economic crises<strong>and</strong> localised impoverishment. 45 Thisissue calls for further scrut<strong>in</strong>y, based onmore focused analysis of survey data aswell as on micro-studies.IV.3 The ‘Th<strong>in</strong>’ Rounds: AnUnresolved Puzzle?We have so far said very little about the‘th<strong>in</strong>’ rounds, <strong>and</strong> the poverty estimatesthat can be calculated from them. YetFigure 1 shows that the recent th<strong>in</strong> rounds,from the 51st through the 54th Round,generate poverty estimates that are hard toreconcile with the qu<strong>in</strong>quennial ‘thick’rounds. If we were to connect up theseNet Production Net Imports Net Change <strong>in</strong> ‘Net Availability’Public Stocks (1+2-3)1985-89 422.7 2.0 -5.3 430.11990 456.9 0.3 5.0 452.11991 447.9 -1.4 0.4 446.11992 446.8 1.3 4.2 443.81993 446.4 2.5 16.6 432.31994 456.3 0.2 16.6 439.91995 448.6 -5.9 -2.3 445.11996 451.7 -6.9 -11.7 456.41997 445.5 -6.7 -4.2 443.01998 455.3 -4.7 11.0 439.61999 456.3 -5.4 25.3 425.62000 452.7 -5.2 30.7 416.8Note: All figures (except first row) are three-year averages centred at the year specified <strong>in</strong> the first column.Source: Calculated from Government of <strong>India</strong> (2002), p S-21.3742Economic <strong>and</strong> Political Weekly September 7, 2002

po<strong>in</strong>ts with the official HCR estimates, wewould get a series <strong>in</strong> which poverty rosebetween 1993-94 <strong>and</strong> 1994-95, fell from1994-95 to the end of 1997, rose verysharply <strong>in</strong> the first half of 1998, <strong>and</strong> thenfell with extraord<strong>in</strong>ary rapidity <strong>in</strong> 1999-2000. As we have seen, the official estimatefor 1999-2000 is too low, <strong>and</strong> the lastth<strong>in</strong> round, the 54th Round, ran for onlythe first six months of 1998, <strong>and</strong> maytherefore not be fully comparable withother rounds. Even so, <strong>and</strong> with due allowancefor corrections, it is very hard to<strong>in</strong>tegrate the poverty estimates based onthe th<strong>in</strong> rounds with the picture that emergesfrom the thick rounds as well as from othersources surveyed <strong>in</strong> this paper.The story is further complicated by thefact that these th<strong>in</strong> rounds were run <strong>in</strong> twoversions, one of which resembled thest<strong>and</strong>ard questionnaire up to <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gthe 50th Round, <strong>and</strong> one of which – theexperimental questionnaire – had differentreport<strong>in</strong>g periods for different goods.Headcount ratios based on the experimentalquestionnaire (not shown <strong>in</strong> Figure 1)are lower than those from the st<strong>and</strong>ardquestionnaire, because the experimentalquestionnaire generated higher reports ofper capita expenditure. However, they alsoshow ris<strong>in</strong>g HCRs from the 52nd throughthe 54th Rounds, <strong>and</strong> the <strong>in</strong>crease cont<strong>in</strong>ues<strong>in</strong>to the 55th Round if we use comparablereport<strong>in</strong>g periods from that round.Based on the experimental questionnaire,a case could be made that the all-<strong>India</strong>HCR has been ris<strong>in</strong>g s<strong>in</strong>ce 1995-96 [Sen2000]. As we have seen, there are goodgrounds for distrust<strong>in</strong>g the experimentalquestionnaire <strong>in</strong> the 55th Round, becauseof the juxtaposition of the seven-day recall<strong>and</strong> 30-day recall data for food-pan <strong>and</strong>tobacco. Quite likely, the ‘reconciliationeffect’ (see Section I.1) pulled down theestimates of per capita expenditure fromthe experimental questionnaire, thus exaggerat<strong>in</strong>gpoverty by this count. Even so,if poverty were genu<strong>in</strong>ely fall<strong>in</strong>g, there isno obvious explanation why the experimentalquestionnaire should show a rise<strong>in</strong> poverty from 1995 through 1998.The Plann<strong>in</strong>g Commission has neverendorsed poverty counts from the th<strong>in</strong>rounds. In part, this has been because ofthe smaller sample sizes. The Plann<strong>in</strong>gCommission needs estimates of HCRs, notjust for all-<strong>India</strong>, but for <strong>in</strong>dividual states,<strong>and</strong> the th<strong>in</strong> rounds are not large enough tosupport accurate estimates for some of thesmaller (of the major) states. But <strong>in</strong>adequatesample size generates variance,not bias, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> any case, the th<strong>in</strong> roundsample sizes are perfectly adequate togenerate accurate estimates for the all-<strong>India</strong> HCRs. The discrepancies <strong>in</strong> Figure 1cannot be expla<strong>in</strong>ed by <strong>in</strong>adequatesample sizes.There are other differences between thick<strong>and</strong> th<strong>in</strong> rounds. For example, the sampl<strong>in</strong>gframe for the 51st, 53rd, <strong>and</strong> 54thRounds was not the census of population,but the ‘economic’ census. In the populationcensus, each household is asked ifit has a family bus<strong>in</strong>ess or enterprise, <strong>and</strong>only such households are <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> thefirst-stage sampl<strong>in</strong>g from the economiccensus when ‘first-stage units’ are drawnwith probability proportional to size. Thismeans that a village with few or no suchhouseholds has only a small or no chanceof be<strong>in</strong>g selected as a first-stage unit. Evenso, when the team reaches the village, allhouseholds are listed <strong>and</strong> have a chanceof be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the sample, so it is unclear thatthis choice of frame makes much difference.Indeed, comparison of various socioeconomic<strong>in</strong>dicators (e g, literacy rates,years of school<strong>in</strong>g, l<strong>and</strong>hold<strong>in</strong>g, or familysize) from the surveys suggests no obviousbreaks between the 51st <strong>and</strong> 53rd Roundson the one h<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> the 52nd Round(which used the population census) on theother. Conversations with NSS <strong>and</strong> Plann<strong>in</strong>gCommission staff sometimes suggestthat there may be other (non-documented)differences <strong>in</strong> the sampl<strong>in</strong>g structure of theth<strong>in</strong> rounds. Certa<strong>in</strong>ly, a tabulation of thepopulation sizes of the first-stage unitsshows that the 52nd Round conta<strong>in</strong>edrelatively few large units compared withthe 51st, 53rd, 54th, <strong>and</strong> 55th rounds; thisis a different issue from the use of theeconomic rather than population census(both the 52nd <strong>and</strong> 55th Rounds use thelatter), <strong>and</strong> the f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g suggests that thefirst-stage units <strong>in</strong> the 52nd Round wereselected differently from other rounds <strong>in</strong>some way that is not documented. Moreover,the measurement of consumption isnot the ma<strong>in</strong> purpose of any of these th<strong>in</strong>rounds, all of which have some otherobjective, so it is possible that consumptionis not so fully or carefully collectedas <strong>in</strong> the qu<strong>in</strong>quennial rounds.In short, there are grounds for scepticismabout the validity of the th<strong>in</strong> rounds forpoverty estimation purposes, <strong>and</strong> this is allthe more so if we remember that aside from<strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g no poverty decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> the laten<strong>in</strong>eties, the th<strong>in</strong> rounds also suggest thataverage per capita expenditure was stagnat<strong>in</strong>gdur<strong>in</strong>g that period – someth<strong>in</strong>g thatis very hard to reconcile with other evidence.Hav<strong>in</strong>g said this, we have not beenable to identify any ‘smok<strong>in</strong>g gun’ thatwould po<strong>in</strong>t to a specific problem with anyof these rounds <strong>and</strong> expla<strong>in</strong> their apparentlyanomalous poverty estimates. Untilthat puzzle is resolved, we see the evidencefrom the th<strong>in</strong> rounds as cast<strong>in</strong>g a shadowof doubt over the <strong>in</strong>terpretation of thepoverty estimates presented earlier <strong>in</strong> thispaper. Perhaps the th<strong>in</strong> rounds <strong>in</strong> the nextfive years will offer some useful clues.VBeyond <strong>Poverty</strong> IndexesThe decl<strong>in</strong>e of poverty <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties,as captured <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>dicators exam<strong>in</strong>ed sofar, can be seen as an example of cont<strong>in</strong>uedprogress dur<strong>in</strong>g that period. Whether therate of progress has been faster or slowerthan <strong>in</strong> the eighties is difficult to say, <strong>and</strong>the answer is likely to depend on how therate of progress is measured. There is, atany rate, no obvious pattern of “acceleration”or ‘slowdown’ <strong>in</strong> this respect.It is important to supplement the evidencereviewed so far, which essentiallyrelates to purchas<strong>in</strong>g power, with other<strong>in</strong>dicators of well-be<strong>in</strong>g relat<strong>in</strong>g, for <strong>in</strong>stanceto educational achievements, lifeexpectancy, nutritional levels, crime rates,<strong>and</strong> various aspects of social <strong>in</strong>equality.This broader perspective reveals that socialprogress <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties has followedvery diverse patterns, rang<strong>in</strong>g from acceleratedprogress <strong>in</strong> some fields to slowdown<strong>and</strong> even regression <strong>in</strong> other respects.The po<strong>in</strong>t is illustrated <strong>in</strong> Figure 7,where simple measures of the progress ofdifferent social <strong>in</strong>dicators <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>etiesare compared with the correspond<strong>in</strong>gachievements <strong>in</strong> the eighties.Elementary education provides an <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>gexample of accelerated progress <strong>in</strong>the n<strong>in</strong>eties. 46 This trend is evident notonly from census data on literacy rates, butalso from National Family Health Surveydata on school participation. To illustrate,school participation among girls aged 6-14jumped from 59 per cent to 74 per centbetween 1992-93 <strong>and</strong> 1998-99. 47 The regionalpatterns are also <strong>in</strong>structive. It isparticularly <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g to note evidence ofrapid progress <strong>in</strong> Madhya Pradesh <strong>and</strong>Rajasthan, demarcat<strong>in</strong>g them clearly fromBihar <strong>and</strong> Uttar Pradesh, the other twomembers of the so-called BIMARU set. 48There is an important po<strong>in</strong>ter here to therelation between public action <strong>and</strong> socialachievements. Indeed, Madhya PradeshEconomic <strong>and</strong> Political Weekly September 7, 2002 3743