Poverty and Inequality in India: a Reexamination - Princeton University

Poverty and Inequality in India: a Reexamination - Princeton University

Poverty and Inequality in India: a Reexamination - Princeton University

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

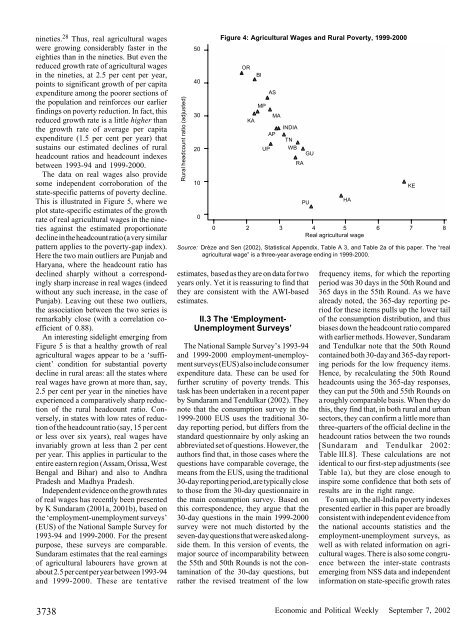

n<strong>in</strong>eties. 28 Thus, real agricultural wageswere grow<strong>in</strong>g considerably faster <strong>in</strong> theeighties than <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties. But even thereduced growth rate of agricultural wages<strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties, at 2.5 per cent per year,po<strong>in</strong>ts to significant growth of per capitaexpenditure among the poorer sections ofthe population <strong>and</strong> re<strong>in</strong>forces our earlierf<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs on poverty reduction. In fact, thisreduced growth rate is a little higher thanthe growth rate of average per capitaexpenditure (1.5 per cent per year) thatsusta<strong>in</strong>s our estimated decl<strong>in</strong>es of ruralheadcount ratios <strong>and</strong> headcount <strong>in</strong>dexesbetween 1993-94 <strong>and</strong> 1999-2000.The data on real wages also providesome <strong>in</strong>dependent corroboration of thestate-specific patterns of poverty decl<strong>in</strong>e.This is illustrated <strong>in</strong> Figure 5, where weplot state-specific estimates of the growthrate of real agricultural wages <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>etiesaga<strong>in</strong>st the estimated proportionatedecl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> the headcount ratio (a very similarpattern applies to the poverty-gap <strong>in</strong>dex).Here the two ma<strong>in</strong> outliers are Punjab <strong>and</strong>Haryana, where the headcount ratio hasdecl<strong>in</strong>ed sharply without a correspond<strong>in</strong>glysharp <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> real wages (<strong>in</strong>deedwithout any such <strong>in</strong>crease, <strong>in</strong> the case ofPunjab). Leav<strong>in</strong>g out these two outliers,the association between the two series isremarkably close (with a correlation coefficientof 0.88).An <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g sidelight emerg<strong>in</strong>g fromFigure 5 is that a healthy growth of realagricultural wages appear to be a ‘sufficient’condition for substantial povertydecl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> rural areas: all the states wherereal wages have grown at more than, say,2.5 per cent per year <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties haveexperienced a comparatively sharp reductionof the rural headcount ratio. Conversely,<strong>in</strong> states with low rates of reductionof the headcount ratio (say, 15 per centor less over six years), real wages have<strong>in</strong>variably grown at less than 2 per centper year. This applies <strong>in</strong> particular to theentire eastern region (Assam, Orissa, WestBengal <strong>and</strong> Bihar) <strong>and</strong> also to AndhraPradesh <strong>and</strong> Madhya Pradesh.Independent evidence on the growth ratesof real wages has recently been presentedby K Sundaram (2001a, 2001b), based onthe ‘employment-unemployment surveys’(EUS) of the National Sample Survey for1993-94 <strong>and</strong> 1999-2000. For the presentpurpose, these surveys are comparable.Sundaram estimates that the real earn<strong>in</strong>gsof agricultural labourers have grown atabout 2.5 per cent per year between 1993-94<strong>and</strong> 1999-2000. These are tentativeRural headcount ratio (adjusted)50403020100Figure 4: Agricultural Wages <strong>and</strong> Rural <strong>Poverty</strong>, 1999-2000ORKA0 2 3 4 5 6 7 8Real agricultural wageSource: Drèze <strong>and</strong> Sen (2002), Statistical Appendix, Table A 3, <strong>and</strong> Table 2a of this paper. The “realagricultural wage” is a three-year average end<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> 1999-2000.estimates, based as they are on data for twoyears only. Yet it is reassur<strong>in</strong>g to f<strong>in</strong>d thatthey are consistent with the AWI-basedestimates.II.3 The ‘Employment-Unemployment Surveys’The National Sample Survey’s 1993-94<strong>and</strong> 1999-2000 employment-unemploymentsurveys (EUS) also <strong>in</strong>clude consumerexpenditure data. These can be used forfurther scrut<strong>in</strong>y of poverty trends. Thistask has been undertaken <strong>in</strong> a recent paperby Sundaram <strong>and</strong> Tendulkar (2002). Theynote that the consumption survey <strong>in</strong> the1999-2000 EUS uses the traditional 30-day report<strong>in</strong>g period, but differs from thest<strong>and</strong>ard questionnaire by only ask<strong>in</strong>g anabbreviated set of questions. However, theauthors f<strong>in</strong>d that, <strong>in</strong> those cases where thequestions have comparable coverage, themeans from the EUS, us<strong>in</strong>g the traditional30-day report<strong>in</strong>g period, are typically closeto those from the 30-day questionnaire <strong>in</strong>the ma<strong>in</strong> consumption survey. Based onthis correspondence, they argue that the30-day questions <strong>in</strong> the ma<strong>in</strong> 1999-2000survey were not much distorted by theseven-day questions that were asked alongsidethem. In this version of events, themajor source of <strong>in</strong>comparability betweenthe 55th <strong>and</strong> 50th Rounds is not the contam<strong>in</strong>ationof the 30-day questions, butrather the revised treatment of the lowBIMPUPASAPMAINDIATNWBGURAPUHAKEfrequency items, for which the report<strong>in</strong>gperiod was 30 days <strong>in</strong> the 50th Round <strong>and</strong>365 days <strong>in</strong> the 55th Round. As we havealready noted, the 365-day report<strong>in</strong>g periodfor these items pulls up the lower tailof the consumption distribution, <strong>and</strong> thusbiases down the headcount ratio comparedwith earlier methods. However, Sundaram<strong>and</strong> Tendulkar note that the 50th Roundconta<strong>in</strong>ed both 30-day <strong>and</strong> 365-day report<strong>in</strong>gperiods for the low frequency items.Hence, by recalculat<strong>in</strong>g the 50th Roundheadcounts us<strong>in</strong>g the 365-day responses,they can put the 50th <strong>and</strong> 55th Rounds ona roughly comparable basis. When they dothis, they f<strong>in</strong>d that, <strong>in</strong> both rural <strong>and</strong> urbansectors, they can confirm a little more thanthree-quarters of the official decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> theheadcount ratios between the two rounds[Sundaram <strong>and</strong> Tendulkar 2002:Table III.8]. These calculations are notidentical to our first-step adjustments (seeTable 1a), but they are close enough to<strong>in</strong>spire some confidence that both sets ofresults are <strong>in</strong> the right range.To sum up, the all-<strong>India</strong> poverty <strong>in</strong>dexespresented earlier <strong>in</strong> this paper are broadlyconsistent with <strong>in</strong>dependent evidence fromthe national accounts statistics <strong>and</strong> theemployment-unemployment surveys, aswell as with related <strong>in</strong>formation on agriculturalwages. There is also some congruencebetween the <strong>in</strong>ter-state contrastsemerg<strong>in</strong>g from NSS data <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>dependent<strong>in</strong>formation on state-specific growth rates3738Economic <strong>and</strong> Political Weekly September 7, 2002