Poverty and Inequality in India: a Reexamination - Princeton University

Poverty and Inequality in India: a Reexamination - Princeton University

Poverty and Inequality in India: a Reexamination - Princeton University

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

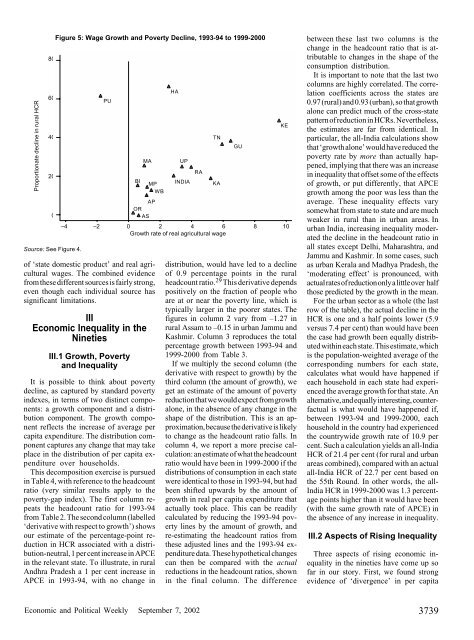

Proportionate decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> rural HCR806040200Source: See Figure 4.Figure 5: Wage Growth <strong>and</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> Decl<strong>in</strong>e, 1993-94 to 1999-2000PU–4 –2 0 2 4 6 8 10Growth rate of real agricultural wageof ‘state domestic product’ <strong>and</strong> real agriculturalwages. The comb<strong>in</strong>ed evidencefrom these different sources is fairly strong,even though each <strong>in</strong>dividual source hassignificant limitations.IIIEconomic <strong>Inequality</strong> <strong>in</strong> theN<strong>in</strong>etiesIII.1 Growth, <strong>Poverty</strong><strong>and</strong> <strong>Inequality</strong>MABIMPWBAPORASIt is possible to th<strong>in</strong>k about povertydecl<strong>in</strong>e, as captured by st<strong>and</strong>ard poverty<strong>in</strong>dexes, <strong>in</strong> terms of two dist<strong>in</strong>ct components:a growth component <strong>and</strong> a distributioncomponent. The growth componentreflects the <strong>in</strong>crease of average percapita expenditure. The distribution componentcaptures any change that may takeplace <strong>in</strong> the distribution of per capita expenditureover households.This decomposition exercise is pursued<strong>in</strong> Table 4, with reference to the headcountratio (very similar results apply to thepoverty-gap <strong>in</strong>dex). The first column repeatsthe headcount ratio for 1993-94from Table 2. The second column (labelled‘derivative with respect to growth’) showsour estimate of the percentage-po<strong>in</strong>t reduction<strong>in</strong> HCR associated with a distribution-neutral,1 per cent <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> APCE<strong>in</strong> the relevant state. To illustrate, <strong>in</strong> ruralAndhra Pradesh a 1 per cent <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong>APCE <strong>in</strong> 1993-94, with no change <strong>in</strong>HAUPINDIARATNKAGUKEdistribution, would have led to a decl<strong>in</strong>eof 0.9 percentage po<strong>in</strong>ts <strong>in</strong> the ruralheadcount ratio. 29 This derivative dependspositively on the fraction of people whoare at or near the poverty l<strong>in</strong>e, which istypically larger <strong>in</strong> the poorer states. Thefigures <strong>in</strong> column 2 vary from –1.27 <strong>in</strong>rural Assam to –0.15 <strong>in</strong> urban Jammu <strong>and</strong>Kashmir. Column 3 reproduces the totalpercentage growth between 1993-94 <strong>and</strong>1999-2000 from Table 3.If we multiply the second column (thederivative with respect to growth) by thethird column (the amount of growth), weget an estimate of the amount of povertyreduction that we would expect from growthalone, <strong>in</strong> the absence of any change <strong>in</strong> theshape of the distribution. This is an approximation,because the derivative is likelyto change as the headcount ratio falls. Incolumn 4, we report a more precise calculation:an estimate of what the headcountratio would have been <strong>in</strong> 1999-2000 if thedistributions of consumption <strong>in</strong> each statewere identical to those <strong>in</strong> 1993-94, but hadbeen shifted upwards by the amount ofgrowth <strong>in</strong> real per capita expenditure thatactually took place. This can be readilycalculated by reduc<strong>in</strong>g the 1993-94 povertyl<strong>in</strong>es by the amount of growth, <strong>and</strong>re-estimat<strong>in</strong>g the headcount ratios fromthese adjusted l<strong>in</strong>es <strong>and</strong> the 1993-94 expendituredata. These hypothetical changescan then be compared with the actualreductions <strong>in</strong> the headcount ratios, shown<strong>in</strong> the f<strong>in</strong>al column. The differencebetween these last two columns is thechange <strong>in</strong> the headcount ratio that is attributableto changes <strong>in</strong> the shape of theconsumption distribution.It is important to note that the last twocolumns are highly correlated. The correlationcoefficients across the states are0.97 (rural) <strong>and</strong> 0.93 (urban), so that growthalone can predict much of the cross-statepattern of reduction <strong>in</strong> HCRs. Nevertheless,the estimates are far from identical. Inparticular, the all-<strong>India</strong> calculations showthat ‘growth alone’ would have reduced thepoverty rate by more than actually happened,imply<strong>in</strong>g that there was an <strong>in</strong>crease<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>equality that offset some of the effectsof growth, or put differently, that APCEgrowth among the poor was less than theaverage. These <strong>in</strong>equality effects varysomewhat from state to state <strong>and</strong> are muchweaker <strong>in</strong> rural than <strong>in</strong> urban areas. Inurban <strong>India</strong>, <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>equality moderatedthe decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> the headcount ratio <strong>in</strong>all states except Delhi, Maharashtra, <strong>and</strong>Jammu <strong>and</strong> Kashmir. In some cases, suchas urban Kerala <strong>and</strong> Madhya Pradesh, the‘moderat<strong>in</strong>g effect’ is pronounced, withactual rates of reduction only a little over halfthose predicted by the growth <strong>in</strong> the mean.For the urban sector as a whole (the lastrow of the table), the actual decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> theHCR is one <strong>and</strong> a half po<strong>in</strong>ts lower (5.9versus 7.4 per cent) than would have beenthe case had growth been equally distributedwith<strong>in</strong> each state. This estimate, whichis the population-weighted average of thecorrespond<strong>in</strong>g numbers for each state,calculates what would have happened ifeach household <strong>in</strong> each state had experiencedthe average growth for that state. Analternative, <strong>and</strong> equally <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g, counterfactualis what would have happened if,between 1993-94 <strong>and</strong> 1999-2000, eachhousehold <strong>in</strong> the country had experiencedthe countrywide growth rate of 10.9 percent. Such a calculation yields an all-<strong>India</strong>HCR of 21.4 per cent (for rural <strong>and</strong> urbanareas comb<strong>in</strong>ed), compared with an actualall-<strong>India</strong> HCR of 22.7 per cent based onthe 55th Round. In other words, the all-<strong>India</strong> HCR <strong>in</strong> 1999-2000 was 1.3 percentagepo<strong>in</strong>ts higher than it would have been(with the same growth rate of APCE) <strong>in</strong>the absence of any <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>equality.III.2 Aspects of Ris<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Inequality</strong>Three aspects of ris<strong>in</strong>g economic <strong>in</strong>equality<strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties have come up sofar <strong>in</strong> our story. First, we found strongevidence of ‘divergence’ <strong>in</strong> per capitaEconomic <strong>and</strong> Political Weekly September 7, 2002 3739