Poverty and Inequality in India: a Reexamination - Princeton University

Poverty and Inequality in India: a Reexamination - Princeton University

Poverty and Inequality in India: a Reexamination - Princeton University

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

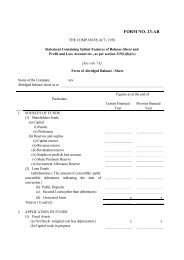

250.0200.0150.0100.050.0Figure 6: Food Intake for Different Per Capita Income Groups, as a Proportion(Per Cent) of Average Intake (1996-97)0.0Cereals <strong>and</strong> millets Fats <strong>and</strong> oils Sugar <strong>and</strong> Jaggery Milk <strong>and</strong> milk productsPer capita <strong>in</strong>come groups (Rs/cap/month) less than 90 90-150150-300 300-600 more than 600Source: Calculated from National Nutrition Monitor<strong>in</strong>g Bureau (1999), Table 6.9. The data relate to ruralareas of eight sample states.disparities produces very sharp contrasts<strong>in</strong> APCE growth between the rural sectorsof the slow-grow<strong>in</strong>g states <strong>and</strong> the urbansectors of the fast-grow<strong>in</strong>g states (Table 3).This is further compounded by the accentuationof <strong>in</strong>tra-urban <strong>in</strong>equality, which isitself quite substantial, bear<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>dthat the change is measured over a shortperiod of six years (Table 5).It might be argued that a temporary<strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> economic <strong>in</strong>equality is to beexpected <strong>in</strong> a liberalis<strong>in</strong>g economy, <strong>and</strong>that this trend is likely to be short-lived.Proponents of the ‘Kuznets curve’ mayeven expect it to be reversed <strong>in</strong> due course.However, Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s experience of sharp <strong>and</strong>susta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> economic <strong>in</strong>equalityover a period of more than 20 years, aftermarket-oriented economic reforms were<strong>in</strong>itiated <strong>in</strong> the late 1970s, does not <strong>in</strong>spiremuch confidence <strong>in</strong> this prognosis. 32 It is,<strong>in</strong> fact, an important po<strong>in</strong>ter to the possibilityof further accentuation of economicdisparities <strong>in</strong> <strong>India</strong> <strong>in</strong> the near future.IVQualifications <strong>and</strong> ConcernsIV.1 Food ConsumptionThere have been major changes <strong>in</strong> <strong>India</strong>’sfood economy <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties. The eightieswere a period of healthy growth <strong>in</strong> agriculturaloutput, food production, <strong>and</strong> realagricultural wages. Dur<strong>in</strong>g the n<strong>in</strong>eties,however, productivity <strong>in</strong>creases sloweddown <strong>in</strong> many states. The quantity <strong>in</strong>dexof agricultural production grew at a lame2 per cent per year or so. The growth ofreal agricultural wages slowed down considerably.And cereal production barelykept pace with population growth. 33The virtual stagnation of per capita cerealproduction <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties has been accompaniedby a gradual switch from net importsto net exports, <strong>and</strong> also by a massiveaccumulation of public stocks. Correspond<strong>in</strong>gly,there has been no <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> estimatedper capita ‘net availability’ of cereals(Table 6). If anyth<strong>in</strong>g, net availabilitydecl<strong>in</strong>ed a little, from a peak of about 450grams per person per day <strong>in</strong> 1990 to 420grams or so at the end of the n<strong>in</strong>eties. Thisis consistent with <strong>in</strong>dependent evidence,from National Sample Survey data, of adecl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> per capita cereal consumption<strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties. Between 1993-94 <strong>and</strong> 1999-2000, for <strong>in</strong>stance, average cereal consumptionper capita decl<strong>in</strong>ed from 13.5 kgper month to 12.7 kg per month <strong>in</strong> ruralareas, <strong>and</strong> from 10.6 to 10.4 kg per month<strong>in</strong> urban areas. 34 This comparison isbased on the ‘uncorrected’ 55th Rounddata, <strong>and</strong> the ‘true’ decl<strong>in</strong>e may be largerstill, given the changes <strong>in</strong> questionnairedesign (Section I.1).The reduction of cereal consumption <strong>in</strong>the n<strong>in</strong>eties may seem <strong>in</strong>consistent withthe notion that poverty has decl<strong>in</strong>ed dur<strong>in</strong>gthe same period. Indeed, this pattern hasbeen widely <strong>in</strong>voked as evidence of ‘impoverishment’<strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eties. If cereal consumptionis decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, how can povertybe decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g?It is worth not<strong>in</strong>g, however, that thedecl<strong>in</strong>e of cereal consumption is not new.A similar decl<strong>in</strong>e took place (accord<strong>in</strong>g toNational Sample Survey data) dur<strong>in</strong>g theseventies <strong>and</strong> eighties, when poverty wascerta<strong>in</strong>ly decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. Hanchate <strong>and</strong> Dyson’s(2000) recent comparison of rural foodconsumption patterns <strong>in</strong> 1973-74 <strong>and</strong>1993-94 sheds some useful light on thismatter. As the authors show, dur<strong>in</strong>g thisperiod per capita cereal consumption <strong>in</strong>rural areas decl<strong>in</strong>ed quite sharply on average(from 15.8 to 13.6 kgs per personper month), but rose among the pooresthouseholds. The decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> the average isdriven by reduced consumption among thehigher expenditure groups. 35The average decl<strong>in</strong>e is unlikely to bedriven by changes <strong>in</strong> relative prices;<strong>in</strong>deed, there has been little change <strong>in</strong> foodprices, relative to other prices, <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>terven<strong>in</strong>gperiod. Instead, this pattern appearsto reflect a substitution away fromcereals to other food items as <strong>in</strong>comes rise(at least beyond a certa<strong>in</strong> threshold). Theconsumption of ‘superior’ food items suchas vegetables, milk, fruit, fish <strong>and</strong> meat didrise quite sharply over the same period,across all expenditure groups. Seen <strong>in</strong> thislight, the decl<strong>in</strong>e of average cereal consumptionmay not be a matter of concernper se. Indeed, average cereal consumptionis <strong>in</strong>versely related to per capita <strong>in</strong>comeacross countries (e g, it is lower <strong>in</strong>Ch<strong>in</strong>a than <strong>in</strong> <strong>India</strong>, <strong>and</strong> even lower <strong>in</strong> theUnited States), <strong>and</strong> the same applies acrossstates with<strong>in</strong> <strong>India</strong> (e g, cereal consumptionis higher <strong>in</strong> Bihar or Orissa than <strong>in</strong>Punjab or Haryana).Food <strong>in</strong>take data collected by the NationalNutrition Monitor<strong>in</strong>g Bureau(NNMB) shed further light on this issue.Aside from detailed <strong>in</strong>formation on food<strong>in</strong>take, the NNMB surveys <strong>in</strong>clude roughestimates of household <strong>in</strong>comes. These areused <strong>in</strong> Figure 6 to display the relationbetween per-capita <strong>in</strong>come <strong>and</strong> food <strong>in</strong>take,for different types of food. The substitutionfrom cereals towards other fooditems with ris<strong>in</strong>g per-capita <strong>in</strong>come emergesquite clearly. 36 This pattern, if confirmed,would fit quite well with the data on changeover time. 37 It also implies that the decl<strong>in</strong>eof average cereal consumption <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>etiesis not <strong>in</strong>consistent with our earlierf<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs on poverty decl<strong>in</strong>e. 38IV.2 Localised Impoverishment<strong>and</strong> Hidden CostsThe overall decl<strong>in</strong>e of poverty <strong>in</strong> then<strong>in</strong>eties does not rule out the possibilityof impoverishment among specific regionsor social groups. That possibility, of course,is not new, but it is worth ask<strong>in</strong>g whetherEconomic <strong>and</strong> Political Weekly September 7, 2002 3741