The Futility of Unification and Harmonization in International ...

The Futility of Unification and Harmonization in International ...

The Futility of Unification and Harmonization in International ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

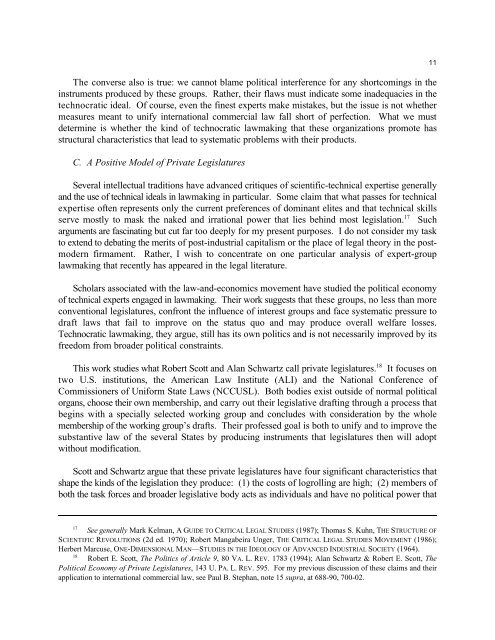

<strong>The</strong> converse also is true: we cannot blame political <strong>in</strong>terference for any shortcom<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> the<strong>in</strong>struments produced by these groups. Rather, their flaws must <strong>in</strong>dicate some <strong>in</strong>adequacies <strong>in</strong> thetechnocratic ideal. Of course, even the f<strong>in</strong>est experts make mistakes, but the issue is not whethermeasures meant to unify <strong>in</strong>ternational commercial law fall short <strong>of</strong> perfection. What we mustdeterm<strong>in</strong>e is whether the k<strong>in</strong>d <strong>of</strong> technocratic lawmak<strong>in</strong>g that these organizations promote hasstructural characteristics that lead to systematic problems with their products.C. A Positive Model <strong>of</strong> Private LegislaturesSeveral <strong>in</strong>tellectual traditions have advanced critiques <strong>of</strong> scientific-technical expertise generally<strong>and</strong> the use <strong>of</strong> technical ideals <strong>in</strong> lawmak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> particular. Some claim that what passes for technicalexpertise <strong>of</strong>ten represents only the current preferences <strong>of</strong> dom<strong>in</strong>ant elites <strong>and</strong> that technical skills17serve mostly to mask the naked <strong>and</strong> irrational power that lies beh<strong>in</strong>d most legislation. Sucharguments are fasc<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g but cut far too deeply for my present purposes. I do not consider my taskto extend to debat<strong>in</strong>g the merits <strong>of</strong> post-<strong>in</strong>dustrial capitalism or the place <strong>of</strong> legal theory <strong>in</strong> the postmodernfirmament. Rather, I wish to concentrate on one particular analysis <strong>of</strong> expert-grouplawmak<strong>in</strong>g that recently has appeared <strong>in</strong> the legal literature.Scholars associated with the law-<strong>and</strong>-economics movement have studied the political economy<strong>of</strong> technical experts engaged <strong>in</strong> lawmak<strong>in</strong>g. <strong>The</strong>ir work suggests that these groups, no less than moreconventional legislatures, confront the <strong>in</strong>fluence <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terest groups <strong>and</strong> face systematic pressure todraft laws that fail to improve on the status quo <strong>and</strong> may produce overall welfare losses.Technocratic lawmak<strong>in</strong>g, they argue, still has its own politics <strong>and</strong> is not necessarily improved by itsfreedom from broader political constra<strong>in</strong>ts.18This work studies what Robert Scott <strong>and</strong> Alan Schwartz call private legislatures. It focuses ontwo U.S. <strong>in</strong>stitutions, the American Law Institute (ALI) <strong>and</strong> the National Conference <strong>of</strong>Commissioners <strong>of</strong> Uniform State Laws (NCCUSL). Both bodies exist outside <strong>of</strong> normal politicalorgans, choose their own membership, <strong>and</strong> carry out their legislative draft<strong>in</strong>g through a process thatbeg<strong>in</strong>s with a specially selected work<strong>in</strong>g group <strong>and</strong> concludes with consideration by the wholemembership <strong>of</strong> the work<strong>in</strong>g group’s drafts. <strong>The</strong>ir pr<strong>of</strong>essed goal is both to unify <strong>and</strong> to improve thesubstantive law <strong>of</strong> the several States by produc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>struments that legislatures then will adoptwithout modification.Scott <strong>and</strong> Schwartz argue that these private legislatures have four significant characteristics thatshape the k<strong>in</strong>ds <strong>of</strong> the legislation they produce: (1) the costs <strong>of</strong> logroll<strong>in</strong>g are high; (2) members <strong>of</strong>both the task forces <strong>and</strong> broader legislative body acts as <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>and</strong> have no political power that1117See generally Mark Kelman, A GUIDE TO CRITICAL LEGAL STUDIES (1987); Thomas S. Kuhn, THE STRUCTURE OFSCIENTIFIC REVOLUTIONS (2d ed. 1970); Robert Mangabeira Unger, THE CRITICAL LEGAL STUDIES MOVEMENT (1986);Herbert Marcuse, ONE-DIMENSIONAL MAN—STUDIES IN THE IDEOLOGY OF ADVANCED INDUSTRIAL SOCIETY (1964).18Robert E. Scott, <strong>The</strong> Politics <strong>of</strong> Article 9, 80 VA. L. REV. 1783 (1994); Alan Schwartz & Robert E. Scott, <strong>The</strong>Political Economy <strong>of</strong> Private Legislatures, 143 U. PA. L. REV. 595. For my previous discussion <strong>of</strong> these claims <strong>and</strong> theirapplication to <strong>in</strong>ternational commercial law, see Paul B. Stephan, note 15 supra, at 688-90, 700-02.