The Futility of Unification and Harmonization in International ...

The Futility of Unification and Harmonization in International ...

The Futility of Unification and Harmonization in International ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

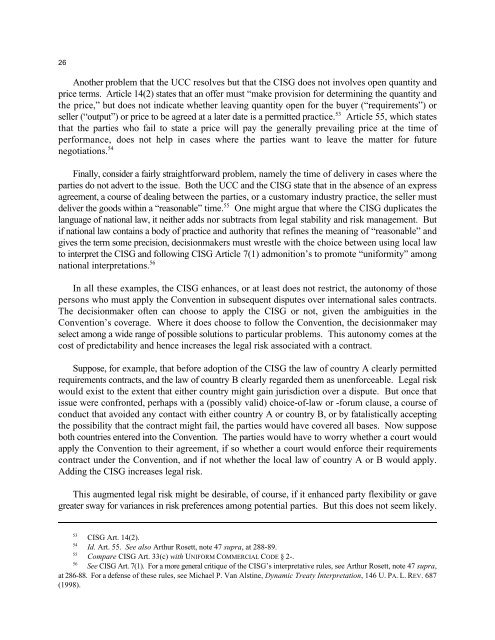

26Another problem that the UCC resolves but that the CISG does not <strong>in</strong>volves open quantity <strong>and</strong>price terms. Article 14(2) states that an <strong>of</strong>fer must “make provision for determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the quantity <strong>and</strong>the price,” but does not <strong>in</strong>dicate whether leav<strong>in</strong>g quantity open for the buyer (“requirements”) or53seller (“output”) or price to be agreed at a later date is a permitted practice. Article 55, which statesthat the parties who fail to state a price will pay the generally prevail<strong>in</strong>g price at the time <strong>of</strong>performance, does not help <strong>in</strong> cases where the parties want to leave the matter for futurenegotiations. 54F<strong>in</strong>ally, consider a fairly straightforward problem, namely the time <strong>of</strong> delivery <strong>in</strong> cases where theparties do not advert to the issue. Both the UCC <strong>and</strong> the CISG state that <strong>in</strong> the absence <strong>of</strong> an expressagreement, a course <strong>of</strong> deal<strong>in</strong>g between the parties, or a customary <strong>in</strong>dustry practice, the seller must55deliver the goods with<strong>in</strong> a “reasonable” time. One might argue that where the CISG duplicates thelanguage <strong>of</strong> national law, it neither adds nor subtracts from legal stability <strong>and</strong> risk management. Butif national law conta<strong>in</strong>s a body <strong>of</strong> practice <strong>and</strong> authority that ref<strong>in</strong>es the mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> “reasonable” <strong>and</strong>gives the term some precision, decisionmakers must wrestle with the choice between us<strong>in</strong>g local lawto <strong>in</strong>terpret the CISG <strong>and</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g CISG Article 7(1) admonition’s to promote “uniformity” amongnational <strong>in</strong>terpretations. 56In all these examples, the CISG enhances, or at least does not restrict, the autonomy <strong>of</strong> thosepersons who must apply the Convention <strong>in</strong> subsequent disputes over <strong>in</strong>ternational sales contracts.<strong>The</strong> decisionmaker <strong>of</strong>ten can choose to apply the CISG or not, given the ambiguities <strong>in</strong> theConvention’s coverage. Where it does choose to follow the Convention, the decisionmaker mayselect among a wide range <strong>of</strong> possible solutions to particular problems. This autonomy comes at thecost <strong>of</strong> predictability <strong>and</strong> hence <strong>in</strong>creases the legal risk associated with a contract.Suppose, for example, that before adoption <strong>of</strong> the CISG the law <strong>of</strong> country A clearly permittedrequirements contracts, <strong>and</strong> the law <strong>of</strong> country B clearly regarded them as unenforceable. Legal riskwould exist to the extent that either country might ga<strong>in</strong> jurisdiction over a dispute. But once thatissue were confronted, perhaps with a (possibly valid) choice-<strong>of</strong>-law or -forum clause, a course <strong>of</strong>conduct that avoided any contact with either country A or country B, or by fatalistically accept<strong>in</strong>gthe possibility that the contract might fail, the parties would have covered all bases. Now supposeboth countries entered <strong>in</strong>to the Convention. <strong>The</strong> parties would have to worry whether a court wouldapply the Convention to their agreement, if so whether a court would enforce their requirementscontract under the Convention, <strong>and</strong> if not whether the local law <strong>of</strong> country A or B would apply.Add<strong>in</strong>g the CISG <strong>in</strong>creases legal risk.This augmented legal risk might be desirable, <strong>of</strong> course, if it enhanced party flexibility or gavegreater sway for variances <strong>in</strong> risk preferences among potential parties. But this does not seem likely.53CISG Art. 14(2).54Id. Art. 55. See also Arthur Rosett, note 47 supra, at 288-89.55Compare CISG Art. 33(c) with UNIFORM COMMERCIAL CODE § 2-.56See CISG Art. 7(1). For a more general critique <strong>of</strong> the CISG’s <strong>in</strong>terpretative rules, see Arthur Rosett, note 47 supra,at 286-88. For a defense <strong>of</strong> these rules, see Michael P. Van Alst<strong>in</strong>e, Dynamic Treaty Interpretation, 146 U. PA. L. REV. 687(1998).