Uilkraals Situation Assessment - Anchor Environmental

Uilkraals Situation Assessment - Anchor Environmental

Uilkraals Situation Assessment - Anchor Environmental

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

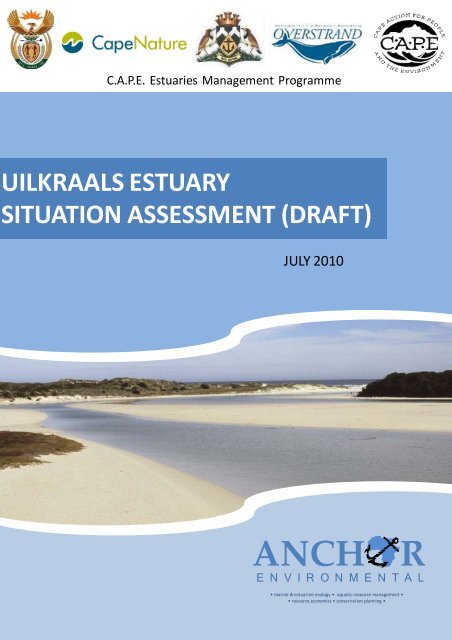

C.A.P.E. Estuaries Management ProgrammeUILKRAALS ESTUARYSITUATION ASSESSMENT (DRAFT)DRAFTJULY 2010ENVIRONMENTALANCH RUniversity of Cape Town,PO Box 34035, Rhodes Gift 7707barry.clark@uct.ac.zaENVIRONMENTAL• marine & estuarine ecology • aquatic resource management •• resource economics • conservation planning •i

seen hundreds and even thousands of waders and terns around the estuary. In February 2010 a total ofonly 60 waders were counted. This is most likely due to a loss in the intertidal feeding habitat whichcovered the entire sandlfat region below and above the causeway. The estuary also seems to havebecome less suitable as a tern roosting site.The <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary is now categorised as a D‐class estuary in terms of its present state of health. Thismeans it is considered to be a ”largely modified” system. Although the estuary currently receives 80% ofits Mean Annual Runoff (MAR), the loss of an important part of the natural hydrology of the estuary hasbeen removed (winter and summer base flows), which has modified the natural condition and caused theestuary to become permanently closed off from the sea. This has resulted in changes to the habitatswithin and around the estuary (i.e. microalgae abundance and saltmarsh areas) and has caused adecrease in the number of bird species, especially waders utilising the estuary. It is likely that theestuary’s condition will continue to deteriorate. Turpie & Clark (2007) listed the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary as ahigh priority estuary for rehabilitation. Alien plant clearance and the removal of the causeway werelisted as the types of requirements needed to rehabilitate the estuary. Increasing the freshwater inflowsand ensuring more natural flows into the system are also needed.Ecosystem servicesEstuaries provide a range of services that have economic or welfare value. In the case of the <strong>Uilkraals</strong>Estuary, the most important of these are the recreational and tourism values of the estuary as well as theprovision of a nursery area for fish. There may be additional services, such as carbon sequestration, butthese are not likely to be of major value.The <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary is a popular tourist destination for local and regional South African tourists. Thearea surrounding the mouth of the estuary has been developed on the west bank in the form of theUilenkraalsmond Holiday Resort, which includes the municipal caravan and camping park as well asassociated recreational amenities located on the site. This establishment is generally full during themajor holiday periods. Birding and recreational opportunities represent an important draw card forvisitors to the estuary.Legislation and management issuesLittle legislation has been designed for estuaries in particular. However, the fact that estuaries containfreshwater, terrestrial and marine components, and are heavily influenced by activities in a much broadercatchment and adjacent marine area, means that they are affected by a large number of policies andlaws. There is also no specific provision for Estuarine Protected Areas. The Department of Water and<strong>Environmental</strong> Affairs Estuary is the primary agency responsible for estuary management in South Africawith a small amount of responsibility (fisheries) attributable to the Deapartment of Agriculture andFishies. <strong>Environmental</strong> management in most instances is devolved to provincial level, aside from waterresources and fisheries which remain a national competancy. At a municipal level, by‐laws are passedwhich cannot conflict with provincial and national laws. The <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary lies wholly within theOverstrand Local Municipality, which falls within the Overberg District Municipality of the Western CapeProvince.Water quality and quantity are mainly controlled under the National Water Act 36 of 1998. This makesprovision for an <strong>Environmental</strong> Reserve which stipulates the quantity and quality of water flow requiredto protect the natural functioning of each water resource, including estuaries. The extent to which an<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>iii<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

Need for protection of the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> EstuaryThe <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary is important in terms of its conservation value. It has unique macrophyte diversityand is a very important birding site. The <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary was included within a set of estuaries in thecountry identified as requiring protection in order to achieve national biodiversity protection targets. Theestablishment of a protected area on the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary is highly recommended and is consideredhighly feasible. Specific recommendations, to be further developed in consultation with stakeholders, areas follows:1. Establish a nature reserve encompassing as much of the land around the estuary as possibleincluding supratidal estuarine habitats;2. Establish a Marine Protected Area on the estuary incorporating the most significant birdhabitats and fish nursery areas as well as a representative section of all habitat types presentin the estuary (mudflat, salt marsh, submerged and emergent vegetation)3. Develop a zonation plan in which 50% of the MPA (not necessarily contiguous) is declared ano‐take zone.The <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary has also been identified as one in which there is a need for rehabilitation. Keymanagement interventions identified in this respect include:1. Restoration of the quantity of freshwater inflows;2. Restoration of water quality;3. Removing significant obstructions to flow; and4. Removal of alien vegetationThe degree to which these factors should be managed to restore the health of the system dependslargely on the vision that is developed for the estuary, and on its future protection status.<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>v<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMSWMABASC.A.P.E.ChlaCPUEDEA&DPDEATDINDRPDRSDWAFERCEHIEWRHIV/AIDSIDPIEPNEMANWAMARMCMMECMm 3MSLPESRDMREIRSARQOSDFTPCWCNCBWater Management AreaBest Attainable StateCape Action Plan for People and the EnvironmentChlorophyll aCatch per unit effortDepartment of <strong>Environmental</strong> Affairs and Development Planning (provincial)Department of <strong>Environmental</strong> Affairs and Tourism (national)Dissolved Inorganic NitrogenDissolved Reactive PhosphateDissolved Reactive SilicateDepartment of Water Affairs and ForestryEcological Reserve CategoryEstuary Health IndexEcological Water RequirementHuman Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Disease SyndromeIntegrated Development PlanningIntegrated <strong>Environmental</strong> ProgrammeNational <strong>Environmental</strong> Management ActNational Water ActMean Annual RunoffMarine & Coastal ManagementMember of provincial Executive CouncilMillion cubic metresMean Sea LevelPresent Ecological StatusResource Directed MeasuresRiver‐Estuary‐InterfaceRepublic of South AfricaResource Quality ObjectivesSpatial Development FrameworkThreshold of Potential ConcernWestern Cape Nature Conservation Board<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>vi<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

TABLE OF CONTENTS1. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................ 92. GEOGRAPHIC AND SOCIO‐ECONOMIC CONTEXT ..................................................................... 112.1 LOCATION AND EXTENT OF THE ESTUARY AND ITS CATCHMENT ....................................................................... 112.2 CATCHMENT CLIMATE, VEGETATION AND DRAINAGE .................................................................................... 132.3 CATCHMENT POPULATION, LAND‐USE AND ECONOMY.................................................................................. 15Population and socio‐economic status ............................................................................................ 15Land‐use .......................................................................................................................................... 16Economy .......................................................................................................................................... 173. ECOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS AND FUNCTIONING OF THE ESTUARY .................................... 183.1 MOUTH DYNAMICS, HYDROLOGY AND CHANNEL SHAPE ................................................................................ 183.2 WATER CHEMISTRY ............................................................................................................................... 223.3 MICROALGAE ...................................................................................................................................... 223.4 VEGETATION ....................................................................................................................................... 23Macroalgae ..................................................................................................................................... 23Submerged macrophytes ................................................................................................................. 23Salt marsh ....................................................................................................................................... 23Reeds and sedges ............................................................................................................................ 24Terrestrial vegetation ...................................................................................................................... 243.5 INVERTEBRATES ................................................................................................................................... 25Benthic invertebrates ...................................................................................................................... 25Hyperbenthic invertebrates ............................................................................................................. 253.6 FISH .................................................................................................................................................. 263.7 BIRDS ................................................................................................................................................ 283.8 CURRENT HEALTH OF THE ESTUARY .......................................................................................................... 31Implications for the estuary ............................................................................................................ 334. ECOSYSTEM SERVICES ............................................................................................................ 344.1 WHAT ARE ECOSYSTEM SERVICES? ........................................................................................................... 344.2 GOODS AND SERVICES PROVIDED BY THE UILKRAALS ESTUARY ....................................................................... 344.3 RAW MATERIALS .................................................................................................................................. 354.4 CARBON SEQUESTRATION ...................................................................................................................... 354.5 WASTE TREATMENT .............................................................................................................................. 364.6 EXPORT OF MATERIALS AND NUTRIENTS .................................................................................................... 364.7 REFUGIA AREAS AND NURSERY VALUE ....................................................................................................... 364.8 GENETIC RESOURCES ............................................................................................................................. 384.9 TOURISM AND RECREATIONAL VALUE ....................................................................................................... 385. LEGISLATION AND MANAGEMENT ISSUES .............................................................................. 405.1 THE MAIN THREATS AND OPPORTUNITIES TO BE CONSIDERED ........................................................................ 405.2 GENERAL POLICY AND LEGISLATIVE BACKGROUND ....................................................................................... 405.3 WATER QUANTITY AND QUALITY REQUIREMENTS ........................................................................................ 47Legislative context ........................................................................................................................... 47The classification process ................................................................................................................ 47<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>vii<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

The reserve determination process ................................................................................................. 475.4 EXPLOITATION OF LIVING MARINE RESOURCES ............................................................................................ 48Legislative context ........................................................................................................................... 48Issues surrounding recreational fishing ........................................................................................... 485.5 LAND USE AND MANAGEMENT OF ESTUARY MARGINS .................................................................................. 48Legislative context ........................................................................................................................... 48Development planning pertaining to the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary ............................................................ 53Issues of surrounding land use and development ........................................................................... 665.6 NON‐CONSUMPTIVE RECREATIONAL USE ................................................................................................... 66Legislation ....................................................................................................................................... 66Management issues ........................................................................................................................ 665.7 POTENTIAL FOR PROTECTED AREA STATUS ................................................................................................. 67Legislative context ........................................................................................................................... 67Potential for protection of the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary ............................................................................. 68Recommendations and procedure for establishing a protected area ............................................. 685.8 POTENTIAL AND NEED FOR RESTORATION ON THE UILKRAALS ESTUARY ........................................................... 696. REFERENCES ........................................................................................................................... 70<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>viii<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

1. INTRODUCTIONThe <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary is one of South Africa’s approximately 279 functional estuaries (Turpie2004). It is one of 21 estuaries within the warm temperate biogeographical region to beclassified as a temporarily open/closed, mixed blackwater system (van Niekerk & Taljaard2007). A medium to large sized estuary, it is estimated to cover an area of 105 ha (Turpie &Clark 2007) (Figure 1), and before the construction of the upstream Kraaibosch Dam hadnaturally hyposaline conditions and a strong tidal exchange when open to the sea. This tidalexchange helped to maintain an open mouth state (Harrison et al. 1995b), but since theconstruction of the dam in 1999, there has been a disruption in the natural freshwater inflows.Owing to its large size, high diversity and abundance of certain biota, the estuary is rated as34 th overall in terms of conservation importance in South Africa (Turpie et al. 2002, Turpie &Clark 2007). It has been identified as a particularly important estuary for macrophyte diversity(macroalgae, submerged macrophytes and saltmarsh) and birds (both residential and migrants)(Barnes 1996).Figure 1: The <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary before it became closed to the sea (Source: Google Earth).Despite the widely acknowledged conservation importance of the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary, the systemis currently under no formal protection. The estuary has been subjected to relatively highlevels of development and anthropogenic disturbance. This includes the construction of theroad bridge over the estuary which affected the natural east to west migration of the mouth.Increasing recreational use of the estuary, including natural resource use (such as fishing) andnon‐consumptive activities (birdwatching and hiking) is putting pressure on the system, whichwill most likely see a change in the character of the area. However, the most significant impacthas been the reduction in freshwater flow into the estuary due to water storage. The<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>9<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

construction of the Kraaibosch dam some 10 km upstream from the estuary in 1999 hasresulted in a reduction in freshwater input, which has had profound effects on the physical andecological functioning of the estuary. Due to the prolonged variation in freshwater inputs, theestuary closed to the sea for an extended period for the first time in January 2009, andremained closed until July 2009. In December of the same year, the estuary enetered anotherprolonged closed phase. This alteration in the natural flow regime will most likely to result in areduction in the frequency and extent of floodplain inundation, and a reduction in scouring ofsediment in the estuary. Further threats to the estuary include increased siltation due toerosion, the loss and destruction of natural habitat by development and alien plant invasion,and deterioration in water quality caused by agricultural and residential pollution.This study forms part of the Cape Action Plan for the Environment (C.A.P.E.) Regional EstuarineManagement Programme. The main aim of the programme is to develop a strategicconservation plan for the estuaries of the Cape Floristic Region (CFR), and to prepare detailedmanagement plans for each estuary. The estuary programme is divided into three phases. Thefirst phase involved the establishment of a regional conservation plan (Turpie & Clark 2007),the development of guidelines for estuary management plans (van Niekerk & Taljaard 2007),and the preparation of detailed management plans for a few selected systems. Of these,<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Consultants cc was tasked with preparing the management plan for the<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary. These studies will then pave the way for preparation of management plansfor the remaining systems in the region in subsequent phases of the programme.This document is the <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong> report for the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary. It providesbackground information on the estuary including the geographic and socio‐economic context,a description of the ecosystem functioning and biodiversity, the legal and planning context,threats to the system, and its conservation importance. This document will form the basis ofthe development of a vision and strategy for the management of the estuary in a participatoryprocess involving stakeholders. Terms of Reference for the study are in Appendix 1.<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>10<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

2. GEOGRAPHIC AND SOCIO‐ECONOMIC CONTEXT2.1 Location and extent of the estuary and its catchmentThe <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary is situated approximately 60 km northwest of Cape Agulhas and 11 kmeast of Danger Point on the south‐west coast within the cool temperate biogeographic regionof South Africa (Whitfield 1998) (Figure 2). It is the first estuary to be found east of DangerPoint (Heydorn & Bickerton 1982). The <strong>Uilkraals</strong> River runs southward and drains into theIndian Ocean 6 km southeast of Gansbaai. The total catchment area of the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuarycovers approximately 105 ha (Turpie & Clark 2007).Figure 2. Map of the south western tip of South Africa. The arrow indicates the relative position of the<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary (adapted from Harrison 2004).Figure 3. Map showing Overberg region in which the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary is located.<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>11<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

The <strong>Uilkraals</strong> catchment lies within the Overberg District Municipality in the Western CapeProvince and the estuary is located within the Overstrand Local Municipality (Figure 3 andFigure 4). The estuary enters the sea at 34˚36’23”S 19˚24’33”E when the estuary mouth isopen (Whitfield 2000). The river is approximately 46 km in length from the mouth to thesource of the Sondagskloof, one of its major tributaries. The junction of the Sondagskloof andthe Perdeberg rivers forms the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> at an approximate elevation of 200 m roughly 30 kmfrom the mouth. In the lower catchment the Boesmans River joins the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> approximately6 km from the mouth. The size of the estuary from the mouth to the the confluence of the<strong>Uilkraals</strong> and Boesmans is approximately 260 ha (Heydorn & Bickerton 1982). A bridgeapproximately 220 m long spans the estuary approximately 800 m from the mouth. Acauseway approximately 120 m in length supports the eastern road access to the bridge whilstthe remaining 100 m is spanned and supported by large concrete pylons (Heydorn & Bickerton1982).Figure 4. Overstrand Local Municipality map showing the main settlements. The <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary(shown by the arrow) is located between Gansbaai and Pearly Beach (Source: Overstrand SDF 2009).<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>12<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

2.2 Catchment climate, vegetation and drainageThe <strong>Uilkraals</strong> River Catchment is relatively small at 313 km 2 , is dominated by Table MountainSandstone (Heydorn & Bickerton 1982) and lies wholly within the Western Cape Province,which receives most precipitation during the winter rainfall season. MAR for the wholecatchment is approximately 22 Mm 3 (van Niekerk, unpubl. data) and the average annualrainfall in the catchment ranges between 500 and 700 mm (Heydorn & Tinley 1980, Heydorn &Bickerton 1982) with peaks in June and July. The river flow is therefore high in winter with runoffdeclining in summer. At Franskraal, located at the estuary mouth, the annual average dailymaximum temperature is 22°, with the monthly average maximum temperature ranging from27°C in February to 18°C in June, July and August. The annual average daily minimumtemperature is 11°C. The settlement of Franskraal receives on average 500‐600 mm annuallywith most of the rain falling in the winter months (South African Rain Atlas 2010).The spatial patterns in the natural vegetation within the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> River Catchment aredetermined primarily by the underlying geology and regional rainfall. The upper catchment ischaracterised by the acidic and nutrient poor Table Mountain Group (TMG) sandstones andquartzites, which are dominated by mountain fynbos. Lower down in the river valley, rocks ofthe Malmesbury Formation outcrop and support limestone fynbos. The mountain fynbosvegetation in the higher lying areas of the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> River catchment remain predominantlyintact. The lower areas of the catchment have been altered by increased anthropogenicactivities, mainly agriculture and alien plant invasion. Natural riparian vegetation along mostof the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> River’s course (with the exeption of the saltmarsh alongside the estuary) hasbeen replaced by invasive exotics, in particular gums, poplars, Port Jackson and rooikrans (Gale1998).Figure 5. Overstrand Local Municipality physical morphology and landscape map (Source: OverstrandSDF 2009).<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>13<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

The Kraaibosch dam (Figure 6) was constructed on the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> River in 1999 to supply thetown of Gansbaai with water for domestic and industrial use and the surrounding areas withwater for irrigation. The dam wall lies appproximately 10 km upriver from the estuary mouth(du Preez & Sasman 1999), covers 102 ha and can hold 5.5 x 10 6 m 3 . According to the damspermit conditions only winter flow is allowed to be retained and all summer flow is let through.Detailed flow records of river inflow, spillage, rainfall and outflow are kept on a daily basis.Data collected over the past 48 years shows that the average annual rainfall (Figure 7) hasremained between 600 and 750 mm per annum. The amount of rain received over the last 10years is in fact comfortably above this annual average, which strongly suggests that recentanomalous mouth closure events are most likely attributable to the construction and operationof the Kraaibosch the dam, as opposed to changes in rainfall. Retaining water in the damdecreases riverine base flows and floods which changes the physical functioning of the estuary.Estuaries are not only reliant on base flow but also require flood peaks to scour them andmaintain their dynamics, something that cannot easily be supported where in‐channel storagedams are developed (DWAF 2004a).The Boesmansrivier which joins the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> approximately 6 km from the mouth also has alarge dam upstream called the Nieuwedam. There is an unknown number of small dams andwater abstraction points by local farmers on the river below the Nieuwedam. The total volumeof water abstracted from these dams is not known though. The Breede Water ManagamentArea (WMA) Internal Strategic Perspective (ISP) anticipated that the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> River Catchment(G40M) would have a 40% increase in summer allocations out of the Kraaibosch Dam (DWAF2004a) indicating increasing demand, through the progressive implementation of agriculturaldevelopment in the catchment.Figure 6. Kraaibosch Dam (Source: Google Earth)<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>14<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

Figure 7: Annual rainfall for the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> River Catchment from 1962 – 2009.2.3 Catchment population, land‐use and economyPopulation and socio‐economic statusThe total population living within the Overstrand Local Municipality, in which the <strong>Uilkraals</strong>River Catchment is located, was estimated at 74 546 in the 2007 StatsSA Community Survey.Population density was estimated at 35 people per square kilometre and total household countwas 24 485. The majority of the population in the Overstrand Local Municipality are classifiedas Coloured (37%) and White (34%), followed by Black Africans (29%) (Local EconomicDevelopment 2008). The overall population of the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> River catchment (G40M) is a smallproportion of the total for the Overstrand Local Municipality as it contains a relatively smallurban area. Larger settlements such as Gansbaai with approximately 20 000 residents andStanford with 8 000 residents are located outside of the boundaries of the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> catchment.The Overberg District Municipality population growth has been declining since 1995, and theaverage annual growth rate is only 3%. If the current trend of population growth continues,the Overberg will soon have a negative growth rate, as is already seen in the Cape AgulhasLocal Municipality (Local Economic Development 2008). Approximately 56% of the populationin the Overberg area is employed, with 20% of the population being unemployed (LocalEconomic Development 2008). Agriculture and trade are the economic sectors with thehighest employment at 20.1% and 16.5%, respectively. The geographic trend in economicactivity along the catchment is predominately agriculturally based in the middle and upper<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>15<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

eaches and tourism and fishing industry based near the mouth. One of the larger tourismdevelopments within the catchment is the Uilenkraalsmond Holiday Resort, located at theestuary mouth, which includes permanent holiday cottages, caravan sites and recreationalamenities.Land‐useThe catchment consists mainly of agricultural areas and an ecological corridor/area, with someprivate conservation areas and other statutory conservation areas. Development within thecatchment includes small urbanised areas along the coast and larger areas developed foragricultural purposes, with agriculture, fruit farming, stock‐farming, viticulture and natureconservation being the main land use activities. Agriculturally based industries dominate in theOverstrand and include wineries, fruit and fynbos cultivation (Overberg Spatial DevelopmentFramework 2004). The Overstrand Local Municipality lists the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> River Catchment as anintensive agricultural resource area (Figure 8).Urban development accounts for a very small proportion of the catchment land cover. Themajor towns in the area, Gansbaai and Stanford, lie adjacent to the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> catchment. Thelargest town within the catchment is Franskraal, which is located at the mouth of the estuaryon the coast.Figure 8. Intensive agricultural resource areas showing the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> River Catchment as being one ofthe larger agricultural areas in the Overstrand (Source: Overstrand SDF 2009).<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>16<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

EconomyAgriculture dominates much of the upper <strong>Uilkraals</strong> River Catchment, with wineries, fruitcultivation and fynbos cultivation being the most important contributors to this sector.Tourism is a major economic contributor across the catchment, through nature basedrecreation and holiday destinations. The estuary is considered a bird watching destination andrecreational fishing remains a draw card. In addition, Pearly Beach and the UilenkraalsmondResort are big attractions to the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> catchment, where the popularity as a holidaydestination results in a fourfold increase in the population over the holiday seasons. TheOverstrand has had the highest positive annual Gross Domestic Product growth in theOverberg District since 1995 (Local Economic Development 2008). In 2008, the Gross DomesticProduct for the Overberg District was estimated to be in the region of R4 billion, equivalent toapproximately only 0.3% of the national GDP (Local Economic Development 2008).<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>17<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

3. ECOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS AND FUNCTIONING OFTHE ESTUARY3.1 Mouth dynamics, hydrology and channel shapeThe <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary has been classified as a temporarily open‐closed estuary (Whitfield 2000),and is a mixed (in terms of salinity), blackwater system (van Niekerk unpubl. data). Whenfunctioning naturally, the estuary has tidal exchange and a high frequency of connection to thesea, similar to the Palmiet and Kleinmond estuaries, but is in a more advanced stage ofprogressive infilling and reduction of the tidal prism (Harrison et al. 1995a). The road bridge,which was constructed in 1973, is approximately 220 m long and crosses the riverapproximately 800 m from the mouth (Figure 9 and Figure 10). It is supported on the easternside by a high embankment of rubble spanning almost two‐thirds of the original high tide riverwidth (Gaigher 1984). The remaining 100 m are supported by concrete pylons, effectivelyhalving the width of the estuary there and concentrating the river flow against the westernbank (Heydorn & Bickerton 1982). In 1978 a 150 m long rubble and rock embankment wasbuilt on the beach in front of the beach facing bungalows, forcing the estuary moutheastwards, away from the caravan park (Heydorn & Bickerton 1982). However, theembankment was quickly eroded by wave and tidal action and a shallow, stagnant pool ofwater and a series of sand dunes formed on the beach in front of the bungalows (Figure 9).In the past the estuary mouth opened over a beach with a relatively flat profile and the openmouth status was probably maintained by strong tidal currents (Harrison 2004). Tidal currentsplay a major role in maintaining a connection with the sea in cool and warm‐temperateestuaries (unlike subtropical estuaries, where river flow is the major factor; Cooper et al. 1999,Cooper 2001). Seasonal closure and migration of the estuary occurs due to strong seasonalvariations of river flow and wave climate where limited river flow allows the formation of asand bar across the estuary mouth.<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>18<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

Figure 9. An aerial view of the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary mouth in October 1979 (altitude of 500m).When functioning naturally, the river enters the sea via a meandering channel across thefloodplain, which opens onto sand flats (Heydorn & Bickerton 1982). The road bridge crossesat the lower reaches of these sand flats. There are several river channels which flow across thesand flats upstream of the bridge (Heydorn & Bickerton 1982). The mouth was originallymobile and in the past could enter the sea at any point between the eastern dune and westernpart of the beach opposite the caravan park (Heydorn & Bickerton 1982). The mouth laterbecame fixed by a combination of factors, including the causeway of the road bridge and thestabilization of both the eastern and western dunes (Heydorn & Bickerton 1982).Figure 10. Picture of the bridge and causeway of the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary facing downstream.<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>19<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

The first time in recorded history that the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary became closed for a long period oftime was in January 2009. It re‐opened six months later for a short period but closed again foran extended period in December 2009. Water storage in the Kraaibosch Dam, approximately10 km upstream from the estuary, has significantly altered the natural freshwater in‐flows tothe estuary while agricultural activities in the upper catchment have introduced an increasedsediment load into the estuary, ultimately resulting in reduced flow over time and an increasedlikelihood of mouth closure of the estuary in low flow periods.The lower reaches of the estuary used to consist of several braided channels that expanded toa single 400 m wide channel at high tide (Harrison et al. 1995b). Water in the area below thebridge is now restricted to two smaller shallow channels, the larger of which ends at the beachin front of the huts at the caravan park (Figure 11). Before mouth closure occurred, tidalinfluence reached beyond the bridge, with the majority of the sandflats becoming inundated athigh tide (Harrison et al. 1995b). Tidal interchange was recorded up to 3 km upstream in a1981 survey (Heydorn & Bickerton 1982). Currently, a very shallow braided channel runsacross the sandflats upstream from the bridge, probably similar to former low tide conditions.The majority of the sandflats are now permanently exposed (Figure 12).Figure 11. The closed estuary mouth facing upstream (left) and the area below the bridge facingdownstream (right, picture taken from the bridge), February 2010.The middle reaches of the estuary consist of a wide meandering channel across a largefloodplain, surrounded by saltmarsh vegetation. Before the road bridge was built, the estuarywas a marine‐dominated tidal lagoon. The large volumes of tidal exchange would have rapidlyreduced any effects of floods, when they did occur (Gaigher 1984). Factors affectingcirculation also affect salinity by altering the volumes of salty water entering the estuary aswell as the ratio of dilution of fresh and salt water (Clark 1977). The obstruction caused by theroad bridge would therefore have changed the circulation and hence salinity regime of theestuary immensely. This would have been most critical during periods of freshwater flooding,by prolonging the extension time of freshwater over tidal sandbanks. This effect would havebeen most intensive in the extensive flood area on the landside of the bridge (Gaigher 1984).<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>20<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

Figure 12. Pictures of the exposed sandflats above the bridge, February 2010.Flows recorded at Kraaibosch Dam (some 10 km upstream of the estuary) are well correlatedwith rainfall in the area. While flows are largely natural in the upper reaches, there aresubstantial decreases in downstream flow during the winter months compared with naturalcondition, and increases in summer flow along parts of the river. Annual flood peaks into theestuary are important, but the impact of a flood also depends to some extent on the base flow,with greater flooding impact when the base flows are higher. The estuary currently receives anestimated 80% of its natural MAR (van Niekerk, unpubl. data), however, an importantcomponent of the natural flow (i.e. winter and summer base flows) has been modified to alarge extent, including reductions in floods that would normally scour the system and maintainthe opening of the estuary to the sea.There is little data on the sediments or on historical sedimentation processes of the <strong>Uilkraals</strong>Estuary. Estuaries contain a mixture of river and marine sediments, the balance of which isdetermined by the amount of water moving in and out of the estuary during a tidal cycle,riverine base flows and floods. The size of particles that can be transported from thecatchment increases with amplified velocity, and larger particles are deposited before smallparticles as flow decreases. Base flows carry relatively little sediment, mostly fine silts, and thisis deposited when freshwater flows are slowed by the pushing effect of incoming sea water.This process generally leads to an accumulation of fine sediments in the lower to middlereaches of the estuary, which results in the channel and inter‐tidal areas becoming muddierand shallower with time. Floods carry a lot of silt from the catchment, and this is depositedwherever floodwaters slow down significantly, such as on the floodplain. They also scour awayaccumulated sediments from the estuary the channel and in the lower inter‐tidal areas. Verylarge floods may scour the floodplain as well. The area of scouring versus deposition dependson the size of the flood.<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>21<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

3.2 Water chemistryThe distribution of saline water in an estuary (the longitudinal salinity distribution) is offundamental importance as it affects the distribution of all biota in the system due to theirdiffering salinity tolerances. River inflow and sea level together determine the penetration ofseawater into the system, thereby determining the salinity profile of the estuary.In 1979 and 1981 surveys showed that salinities below the bridge ranged from 35.5‰ at themouth to 26‰ at the bridge. The main channel had a salinity of 20‰ 2 km from the mouthand 0‰ only 500 m further upstream (Heydorn & Bickerton 1982). Harrison (2004) measuredsalinities at six stations along the estuary and reported a mean value of 15.43‰ (SE ± 2.11).Surface water temperature was recorded as 24.5˚C to 25.5˚C at 400 m and 500 m from themouth respectively in the 1979 survey (Heydorn & Bickerton 1982). At the same sampling sitesdissolved oxygen concentrations of 9.8 mg/l and 10.8 mg/l were measured, with a highermeasurement of 13.0 mg/l near algae at the latter (Heydorn & Bickerton 1982). Harrison(2004) measured a mean temperature of 17.33˚C (SE ± 0.27), a mean dissolved oxygenconcentration of 8.49 (SE ± 0.11) mg/l and a mean turbidity of 5.33 (SE ± 0.88) NTU. Extendedmouth closure events will affect the water chemistry of the estuary. The estuary is no longerflushed by the sea or freshwater as frequently as it was in the past and this could result eitherin hypersaline conditions or fresh conditions developing within the estuary, depending on theamount of freshwater inflows and the amount of evaporation.3.3 MicroalgaeMicroalgae in estuaries comprise unicellular algae that live either suspended in the watercolumn (termed phytoplankton) or benthically on rocks or sediments in the estuary (termedmicrophytobenthos or benthic microalgae). These microalgae (i.e. phytoplankton andmicrophytobenthos) are very important in estuarine systems as they are generally the mainsource of primary production in the estuary.Phytoplankton communities in estuaries are influenced by salinity, generally dominated byflagellates where river flow dominates and by diatoms in marine dominated areas. Diatomsare most common in the area of the estuary where the salinity is in the region of 10‐15‰,often referred to as the River Estuary Interface (REI) zone. Phytoplankton biomass in anestuary is also generally at its maximum in this region. Biomass of phytoplankton in estuariesvaries widely and may range from 0‐210 µgChla/l (Adams et al. 1999). If nutrientconcentrations in an estuary are high (particularly in the case of nitrogen) then phytoplanktonbiomass in the estuary is generally high too. Under extreme conditions, when nutrient levelsare very high, certain toxic dinoflagellate species may form dense blooms known as red tides.Less is known about benthic microalgae (microphytobenthos) in estuaries than phytoplankton.Values for benthic microalgae biomass are often reported in different units which makescomparisons between estuaries difficult. Currently there is no available information onmicroalgae in the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary.<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>22<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

3.4 VegetationThere are four main vegetation communities associated with the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary: macroalgae,submerged macrophytes, reeds and sedges, and salt marsh.Heydorn & Bickerton (1982) recorded 13 species of semi‐aquatic plants in and around the<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary. These included Crassula glomerata, Plantago carnosa, triglochin bulbosum,Scirpus littoralis, Sebaea minutiflora, Sebaea albens, Spergularia marginata, Cotula eckloniana,Chenolea diffusa, Samolus deis and Limonium scabrum.MacroalgaeMacroalgae can be indicative of water quality and nutrient enrichment. Macroalgae may beintertidal (intermittently exposed) or subtidal (continually submerged) and can be attached tohard or soft substrata or they may float (Adams et al. 1999). Opportunistic macroalgae arefound in temporary closed estuaries like the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> as they can tolerate fluctuating salinities.During a survey in 1981 the filamentous algae Enteromorpha and Cladophora were recorded inthe estuary and Ulva beds were present under the road bridge (Heydorn & Bickerton 1982).Enteromorpha and Cladorphora belong to the family Chlorophyta, and are often found toextend further into estuaries due to their salinity tolerance (Adams et al. 1999).Submerged macrophytesThe high macrophyte diversity in the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary is of conservation importance. Thereare approximately 2 ha of submerged macrophytes in the estuary, which provide an importanthabitat for invertebrates and juvenile fish. Submerged macrophytes are plants rooted in bothsoft subtidal and low intertidal substrata, which are completely submersed for most states ofthe tide (Adams et al. 1999). Submerged macrophyte beds support diverse and abundantinvertebrate and juvenile fish communities (Whitfield 1984, 1989). Primary productivity ofsubmerged macrophytes is high and on par with the most productive plant habitats in marineand terrestrial ecosystems (Day 1981, Fredette et al. 1990). Adams et al. (1999) found in salinewaters in the region, Zostera capensis is prevalent. Submerged macrophytes are important intheir provision of food for epifaunal and benthic invertebrate species as well as nursery areasfor juvenile fish through the provision of food, shelter and protection (Adams et al. 1999).Salt marshSalt marshes in estuaries are a source of primary production and provide habitat and food for avariety of faunal species (Adams et al. 2006). The degree of tidal flushing is important indetermining how much nutrients they release into the water column (Childers & Day 1990).An open mouth is important as this maintains the intertidal salt marsh community. Salt marshplants are distributed away from the water’s edge along an inundation gradient (Figure 13).Intertidal salt marsh occurs between the limits of the high and low tide ranges, while supratidalmarsh occurs above the intertidal zone and is only normally flooded during spring tide and<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>23<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

other associated high water levels. Floodplain marshes are normally elevated above the rest ofthe estuary, and are normally only covered with water during large flood events.Mucina et al. (2003) described and classified 11 salt marsh plant communities at the <strong>Uilkraals</strong>Estuary. Dominant species included Salicornia meyeriana, Sarcocornia perennis agg., S.capensis, S. decumbens, Bassia diffusa, Limonium sp. nova, Juncus kraussii subsp. kraussii,Sporobolus virginicus and Triglochin bulbosa. In a 1981, study the saltmarsh covered an area ofapproximately 1.3 ha or 0.6% of the studied estuarine region (Heydorn & Bickerton 1982) andhad the highest cover (95%) of all recorded vegetation types. A more recent vegetation studyrecorded approximately 38 ha of saltmarsh, which is still the highest cover of all recordedvegetation types and is of high conservation importance.Figure 13. Picture of the upper channel and saltmarsh area facing upstream, February 2010.Reeds and sedgesReeds and sedges act as natural biological filters, they are important for bank stabilisation asthey are rooted in soft intertidal or shallow subtidal strata (Adams et al. 1999). Reeds andsedges contribute to the diversity of aquatic life, particularly the avifauna (Coetzee et al. 1997).Terrestrial vegetationParsons (1982) identified 10 main terrestrial plant communities around the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary,including the saltmarsh (Error! Reference source not found.). These can be consolidated intofive plant formations visually: low shrubland (0.25‐1.0 m), mid‐high shrubland (1‐2 m),woodland, herbland and grassland. In the study area (205 ha) the low shrubland was the mostextensive (39 ha), followed by the herbland (37 ha) and woodland (32 ha). Mid‐high shrubland<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>24<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

covered 19 ha and grassland 1.3 ha. Open sand, including the beach, made up 46 ha. Fynboscommunities made up fairly large patches in the study area with a total cover of 56 ha or27.3% of the study area. Dense stands of exotic vegetation surround the estuary with the maininvader being the rooikrans Acacia cyclops (Heydorn & Bickerton 1982).3.5 InvertebratesInvertebrates inhabiting estuaries can be divided into a number of sub‐groups based on wherethey reside in the estuary. Zooplankton live mostly in the water column, benthic organismslive in the sediments on the bottom and sides of the estuary channel, and hyperbenthicorganisms live just above the sediment surface. Benthic organisms are frequently furthersubdivided into intertidal (those living between the high and low water marks on the banks ofthe estuary) and subtidal groups (those living below the low water mark). Only limitedinformation on some benthic and hyperbenthic species is available for the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary,summarised below.Benthic invertebratesDuring a 1955 survey, before the construction of the road bridge, a good population ofbloodworms Arenicola loveni, sandprawns Callianassa kraussi and mudprawns Upogebiaafricana were found both up‐ and downstream of the foot bridge (Heydorn & Bickerton 1982,Gaigher 1984). In 1973 a strong, viable population of bloodworms was reported in the tidallyexposed sandbanks of the estuary reaching at least 2 km upstream (Gaigher 1984). Threeyears later, after the erection of the road bridge and the long rubble embankment on which itwas built, no bloodworms were found above the bridge, which is situated approximately 800 mfrom the mouth. Another survey in 1979 confirmed the extinction of the bloodworm in theestuary. A very small juvenile bloodworm population was found in a permanent seawater poolon the beach adjacent to the estuary mouth (Gaigher 1984). The associated change in thesalinity regime of the estuary caused by the construction of the road bridge is the most likelycause of the loss of this species from the estuary.In December 1979 sandprawns and mudprawns were found up and downstream of the newroad bridge, with sandprawns being more abundant and more widely distributed. Mudprawndistribution ended abruptly 100 m upstream of the bridge (Heydorn & Bickerton 1982). InMarch 1981, sandprawns were found in abundance from the mouth across the floodplain towhere freshwater conditions prevailed. Only a few mudprawn burrows were noted (Heydorn& Bickerton 1982).Hyperbenthic invertebratesThe crown crab Hymenosa orbiculare and the hermit crab Diogenes brevirostris were abundantnear the road bridge in 1979, while smaller numbers of the crab Cyclograpsus punctatus werefound in the same area. In 1981 large numbers of C. punctatus were found just above thebridge, as well as large numbers of the shrimp Palaemon pacificus (Heydorn & Bickerton 1982).<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>25<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

3.6 FishEstuaries provide an extremely important habitat for fish in southern Africa. The vast majorityof coastal habitat in southern Africa is directly exposed to the open ocean, and as such issubject to intensive wave action throughout the year (Field & Griffiths 1991). Estuaries insouthern Africa are thus disproportionately important relative to other parts of the world, inthat they constitute the bulk of the sheltered, shallow water inshore habitat in the region.Juveniles of many marine fish species in southern Africa have adapted to take advantage ofthis situation, and have developed the necessary adaptations to enable them to persist inestuaries for at least part of their life cycles. There are at least 100 species that show a clearassociation with estuaries in South Africa (Whitfield 1998). Most of these are juveniles ofmarine species that enter estuaries as juveniles, remain there for a year or more beforereturning to the marine environment as adults or sub‐adults where they spawn, completingthe cycles. Several other species also use estuaries in southern Africa, including some that areable to complete their entire life cycles in these systems, and a range of salt tolerantfreshwater species and euryhaline marine species. Whitfield (1994) has developed a detailedclassification system of estuary associated fishes in southern Africa. He recognized five majorcategories of estuary associated fish species and several subcategories (Table 1).Table 1. Classification of South African fish fauna according to their dependence on estuaries (Whitfield1994)CategoryIIaIbIIIIaIIbIIcIIIIVVDescriptionTruly estuarine species, which breed in southern African estuaries; subdivided as follows:Resident species which have not been recorded breeding in the freshwater or marineenvironmentResident species which have marine or freshwater breeding populationsEuryhaline marine species which usually breed at sea with the juveniles showing varyingdegrees of dependence on southern African estuaries; subdivided as follows:Juveniles dependant of estuaries as nursery areasJuveniles occur mainly in estuaries, but are also found at seaJuveniles occur in estuaries but are more abundant at seaMarine species which occur in estuaries in small numbers but are not dependant onthese systemsEuryhaline freshwater species that can penetrate estuaries depending on salinitytolerance. Includes some species which may breed in both freshwater and estuarinesystemsObligate catadromous species which use estuaries as transit routes between the marineand freshwater environmentsFish species in categories I, II, and V as defined by Whitfield (1994) are all wholly or largelydependent on estuaries for their survival and are hence the most important from an estuaryconservation perspective. These species need to receive most attention from a managementperspective.<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>26<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

Because the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary is categorised as a cool‐temperate open‐closed system itsicthyofaunal composition is likely to be consistent with estuaries in the same category as fish inestuaries respond to their environment in a consistent manner and estuaries with similarhabitats and environmental regimes support similar species assemblages (Whitfield 1998).Harrison (2005) described species caught during extended field research carried out in the1990s, with open cool‐temperate estuaries having an average of 6.8 species captured perestuary. The numerically dominant species caught included harder Liza richardsonii, capesilverside Atherina breviceps and estuarine round‐herring Gilchristella aestuaria. KobArgyrosomus sp., shad Pomatomus saltatrix , flathead mullet Mugil cephalus , and cape whitecatfish Galeicthys feliceps also contributed to the overall biomass (Harrison 2005). In opencool‐temperate estuaries like the <strong>Uilkraals</strong>, Harrison (2005) found that they did not appear tocontain any unique taxa, instead comprising of a mix of widespread and endemic species whichprefer cooler waters (e.g. Cape silverside and harder).G F van Wyk recorded white steenbras Lithognathus lithognathus, mullet (Family: Mugilidae)and nude goby Caffrogobius nudiceps in the estuary in 1955. During a 1981 site visit thepresence of mullet in abundance was noted as well as the presence of white steenbras and theKnysna sandgoby Psammagobius knysnaensis in smaller numbers (Heydorn & Bickerton 1982).White steenbras is a category IIa species and is dependent on estuaries as a nursery area for atleast the first year of life (Whitfield 1994). Harrison et al. (1995b) recorded four species of fishin the estuary; Cape silverside, Knysna sand goby, harder, and flathead mullet.An ichthyological survey at the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary was conducted in 2006. Ten hauls were doneat 10 sampling sites, covering a total sampling area of 3000 m 2 . 11 species of fishes wererecorded (Table 2). Three of these were likely to be breeding in the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary; Capesilverside, nude goby, and the Knysna sand goby. One species, flathead mullet, was likely to bedependent on the estuary as a nursery area for at least its first year of life. Another fivespecies were at least partially dependent on the estuary as a nursery area; Cape soleHeteromycteris capensis, groovy mullet Liza dumerilii, blackhand sole Soleo bleekeri, harder,and white stumpnose Rhabdosargus globiceps.In total, nine species (82% of the fish species recorded from the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary) can beregarded as either partially or completely dependent on the estuary for their survival. Themost abundant species in terms of numbers was the Knysna sand goby, followed by harder(Table 2). Both species are at least partially dependant on the estuary. In terms of biomasssandshark contributed most to the total biomass in the system, followed by harders. However,sandsharks do not rely on estuaries as part of their life cycle.<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>27<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

PiscivoresTable 3. Water‐associated birds recorded at <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary (Summers et al. 1976; Heydorn &Bickerton 1982; A. Terörde, unpubl. data).Invertebrate feedersAfrican Darter Anhinga rufa African Oystercatcher Haematopus moquiniAfrican Fish‐eagle Haliaeetus vocifer African Sacred Ibis Threskiornis aethiopicusAfrican Spoonbill Platalea alba Bar‐tailed Godwit Limosa lapponicaBlack Stork Ciconia nigra Blacksmith Lapwing Vanellus armatusCape Gannet Morus capensis Blackwinged Stilt Himantopus himantopusCape Cormorant Phalacrocorax capensis Cape Wagtail Motacilla capensisCaspian Tern Sterna caspia Common Greenshank Tringa nebulariaCommon Tern Sterna hirundo Common Ringed Plover Charadrius hiaticulaCrowned Cormorant Phalacrocorax coronatus Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucosGiant Kingfisher Megaceryle maxima Eurasian Curlew Numenius arquataGreat Egret Casmerodius albus Curlew Sandpiper Calidris ferrugineaGreyheaded Gull Larus cirrocephalus Grey Plover Pluvialis squatarolaGrey Heron Ardea cinerea Kittlitz's Plover Charadrius pecuariusHartlaub's Gull Larus hartlaubii Little Stint Calidris minutaKelp Gull Larus dominicanus Marsh Sandpiper Tringa stagnatilisLittle Egret Egretta garzetta Ruddy Turnstone Arenaria interpresMalachite Kingfisher Alcedo cristata Sanderling Calidris albaOsprey Pandion haliaetus Terek Sandpiper Xenus cinereusPied Kingfisher Ceryle rudis Three‐banded Plover Charadrius tricollarisReed Cormorant Phalacrocorax africanis Whimbrel Numenius phaeopusSandwich Tern Sterna sandvicensis White‐fronted Plover Charadrius marginatusSwift Tern Sterna bergii HerbivoresWhite‐breasted Cormorant Phalacrocorax lucidus Common Moorhen Gallinula chloropusEgyptian GooseRed‐knobbed CootYellow‐billed DuckAlopochen aegyptiacaFulica cristataAnas undulataTable 4. Summary of bird count results conducted at the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary.January 1976(Summers et al. 1976)January 1976(Summers unpublisheddata)December 1979(Heydorn & Bickerton1982)January 1981(Ryan et al. 1988)February 1996(Barnes 1996)February 2010(A. Terörde, unpub.data)Number ofspeciesTotalabundanceWaderabundanceMost abundant species32 Not counted 774 Waders: Curlew Sandpiper (480)17 4864 720 Sandwich Tern (2000)Waders: Curlew Sandpipers(440)26 5879 584 Sandwich Tern (5000)Waders: Curlew Sandpiper (480)24 6755 880 Common Tern (4720)Waders: Curlew Sandpiper (534)30 2180 1041 Common Tern (513)Waders: Curlew Sandpiper (421)22 435 60 Kelp Gull (310)Waders: Whimbrel (17)<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>29<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

For this study, a count of water‐associated birds was conducted in late February 2010, whensummer migrant numbers are usually maximal. Birds were recorded from the mouth to thesection of the estuary where the wider channel becomes a series of smaller braided channels,approximately 3 km from the mouth.Counts during this study showed a drastic decrease in bird numbers compared to previousyears, while diversity was not affected as much (Table 4). Only 435 individuals were recorded,the majority of these being Kelp Gulls (310 individuals). Most birds (89%) were found in thesandflats above the bridge (Error! Reference source not found.). Ten species were piscivoresand 12 species were invertebrate‐feeding waders. No herbivores were recorded. Compared tothe study by Barnes (1996) the proportion of invertebrate‐feeders, piscivores and herbivoreswas similar. Barnes (1996) recorded 15 species of piscivores, 18 species of invertebratefeedersand one species of herbivore (Egyptian Goose).The low numbers can be explained by the significant decrease in the numbers of CurlewSandpipers, as well as only a small number of terns being present (32 individuals) as comparedto previous counts (Error! Reference source not found.). Curlew Sandpiper has been recordedat the estuary in high numbers during every previous survey conducted (Error! Referencesource not found.). It is an Arctic‐breeding migratory species, and is found in southern Africafrom August/November to March/April. It forages for nereid worms, snails and crustaceansmainly in the intertidal area of coastal lagoons and estuaries and on sheltered open shores withmuch stranded algae (Hockey et al. 2005). The estuary was closed to the sea during the studyand had been closed for approximately two months. Therefore, the large inter‐tidal feedinghabitat which covered the entire sandflat region below and above the road bridge was lost.Most inter‐tidal invertebrates had probably desiccated and died or migrated elsewhere. Whilemany sandprawn burrows were still present, these animals are able to burrow deeper to a levelof sufficient moisture in dry times and are often found in closed systems. They are also verytolerant of varying salinities (Forbes 1974). Due to their large size and the depth of theirburrows it is unlikely that sandprawns can be utilised as prey by small invertebrate‐feedingwaders.Kelp Gulls were recorded roosting for the first time in high numbers at <strong>Uilkraals</strong> with 310individuals recorded (Table 5). Barnes (1996) recorded 67 and Ryan et al. (1988) recorded 77individuals. On the day of the count a strong south‐easterly wind was blowing and it is possiblethat this species seeks shelter in the estuary sporadically. Similar numbers of Kelp Gulls were,however, still present the following two days, even after the wind had died down. The lownumbers of terns recorded are of particular concern as this site was once a major roost forseveral tern species including the Caspian Tern, Sandwich Tern and Swift Tern, of which ithosted 6.8%, 2.8% and 6.6% respectively of the south‐western Cape’s population (Barnes1996). Whimbrel has previously been recorded in high numbers at the estuary (76 and 65individuals) making it the second largest population in the south‐western Cape after LangebaanLagoon (Barnes 1996). Only 17 individuals were recorded in this study. Whimbrel are relativelysensitive to disturbance and higher levels of recreational use of the estuary by people may be acontributing factor, in addition to the loss of intertidal feeding habitat.In addition to the changes associated with the building of the bridge and the closure of themouth, disturbance would have increased with the size of the surrounding settlements andamount of people utilizing the adjoining caravan park and estuary for recreational purposes.<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>30<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

Table 5. Results of the waterbird count (February 2010). Area 1: mouth to bridge; Area 2: bridge tosaltmarsh (sandflats); Area 3: channel through to saltmarsh.Piscivores Area 1 Area 2 Area 3 TOTALCape Cormorant 1 1Caspian Tern 4 2 6Common Tern 12 12Grey Heron 1 1Hartlaub's Gull 8 8Kelp Gull 310 310Little Egret 1 11 12Reed Cormorant 1 1Sandwich Tern 1 1Swift Tern 13 13Invertebrate‐feedersBlacksmith Lapwing 2 3 5Cape Wagtail 2 2 4Common Sandpiper 1 1Curlew Sandpiper 12 12Common Greenshank 1 1African Oystercatcher 4 4Ruff 4 4Sacred Ibis 2 2Terek Sandpiper 3 3Whimbrel 17 17White‐fronted Plover 9 7 16Wood Sandpiper 1 1Total number of individuals 24 387 24 435Total number of species 6 15 6 223.8 Current health of the estuaryWhitfield (2000) conducted an assessment on the condition of estuaries of the entire SouthAfrican coast. The estuaries were broadly classified as follows:• Excellent: estuary in near pristine condition (negligible human impact)• Good: no major negative anthropogenic influences on either the estuary or catchment(low impact)• Fair: noticeable degree of ecological degradation in the catchment and/or estuary(moderate impact)• Poor: major ecological degradation arising from a combination of anthropogenicinfluences (high impact)The <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary was classified by Whitfield (2000) as being in a fair condition. A morerecent health assessment found that the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary has an Estuarine Health Index (EHI)score of 55 (van Niekerk, unpubl. data). The EHI assesses the degree to which the current stateresembles the reference (i.e. natural) condition. Once the natural hydrological conditions havebeen described, specialists assess the condition of the estuary in terms of a range of<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>31<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

iophysical variables. The current state is then scored for each of these variables on a scale of0 (no resemblance to original state) to 100 (same as natural state). The health scores andoverall score are summarised in Table 6. Although the estuary currently receives some 80% ofits natural MAR, an important part of the hydrology and natural functioning of the estuary hasbeen removed (winter and summer base flows) which affects the mouth conditionsignificantly. The similarity score given for the hydrology of system is 50% of the naturalcondition, which is lower than the percentage in natural MAR (80% of natural). This is becausean important component of the natural flow regime has been modified to a large extent, thehydrodynamics and mouth condition (0% of natural condition) are severely altered. Thereduction in flow has also had an impact on the water quality of the system, both due to thereduced ability to dilute pollution and due to the increase in polluted return flows as a result ofwater use for irrigation. The reduced flows may have also altered the physical habitat of theestuary in that the depth and profile have changed. There has been a recorded 81%transformation in the 1 km buffer zone of the estuary (van Niekerk, unpub. data), most likely aconsequence of increased alien vegetation and reduced flows.The reduction in flows has also resulted in considerable changes to the biota of the estuary.Primary productivity by microalgae is thought to have increased due to the nutrient input andreduction in flushing of the estuary. Being a blackwater system, the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> is naturallyoligotrophic and because the water is being retained in the estuary for an extended period oftime, the primary productivity has increased substantially. Plants have also been significantlyaffected. Mouth closure for such extended periods can lead to a significant reduction insaltmarsh vegetation. Saltmarsh cannot survive inundation which is caused by the permanentrise of the water level in the estuary due to a closed mouth. A reduced cueing effect toestuarine dependent invertebrate and fish species could result in a reduction in nurseryfunction, abundance and diversity of species. Birds have also been significantly affected by theclosure of the estuary. The large intertidal feeding habitat which covered the entire sandflatregion below and the above the causeway has been lost, resulting in a severe decrease inwader numbers. The estuary has also become less suitable as a tern roost. The score of 80%allocated to birds is most likely an over estimate and has become even lower as the estuarycontinues to remain closed off from the sea.Table 6. The Estuarine Health Index scores allocated to the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary (Present State)VARIABLESCORE (% resemblance to natural condition)Hydrology 50Hydrodynamics and mouth condition 0Water quality 70Salinity 50Total Water Quality Score 62Physical habitat 70Habitat health score 45.5Microalgae 35Plants (macrophytes) 70Invertebrates 70Fish 75Birds 80Biological health score 64OVERALL EHI SCORE 55<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>32<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

The overall health score of 55 translates into a Present Ecological Status of a D, which is classedas a largely modified system (Table 7).Although the Present State of the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary currently falls within an Ecological CategoryD, it is likely that the estuary is on a negative trajectory of change, because of the extremelylow base flows under the Present State. Turpie & Clark (2007) listed the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary as ahigh priority estuary in need of rehabilitation. Alien plant clearance and the removal of thecauseway were listed as the types of requirements needed to rehabilitate the estuary.Increasing freshwater inflow and ensuring more natural flows into the system are also needed.Table 7. Relationship between Estuarine Health Score, Present Ecological Status (PES) classification,and how it is understood.EHI Score PES General description91 – 100 A Unmodified, natural76 – 90 B Largely natural with few modifications61 – 75 C Moderately modified41 – 60 D Largely modified21 – 40 E Highly degraded0 – 20 F Extremely degradedImplications for the estuaryThe estuary is degrading under the current flows. The main consequences of maintaining the<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary in an Ecological Category D through these flows are considered to be asfollows:1. Excessive (or nuisance) macrophyte growth during the late summer months in theupper reaches, particularly if nutrient inputs are not reduced, negatively impacting onwater intake systems, recreational usage and aesthetics (i.e. ‘loss of value’).2. Reduced cueing effect to estuarine dependent invertebrate and fish species andresulting reduction in nursery function.3. A loss of saltmarsh through inundation or dessication if the estuary remains closed tothe sea.4. A further decrease in bird numbers as the estuary becomes less suitable for wadersand terns. Birds that require an inter‐tidal feeding area are severely affected.<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>33<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

Table 8. Ecosystem goods, services and attributes based on definitions by Costanza et al. (1997) thatare likely to be provided by temperate South African estuaries (Turpie 2007)GoodsEcosystem Goods,Services & AttributesDescriptionImportance inestuariesFood, medicines Production of fish and food plants; medicinal plants HighRaw materialsProduction of craftwork materials, construction materials andfodderMediumServicesAttributesGas regulation Carbon sequestration, oxygen and ozone production, LowClimate regulation Urban heat amelioration, wind generation LowErosion control andsediment retentionWaste treatmentRefugiaNursery areasExport of materialsand nutrientsGenetic resourcesStructure andcompositionPrevention of soil loss by vegetation cover, and capture of soil inwetlands, added agricultural (crop and grazing) output inwetlands/floodplainsBreaking down of waste, detoxifying pollution; dilution andtransport of pollutantsCritical habitat for migratory fish and birds, important habitats forspeciesCritical breeding habitat,Nurseries for marine fishExport of nutrients and sediments to marine ecosystemsMedicine, products for materials science, genes for resistance toplant pathogens and crop pests, ornamental speciesSpecies diversity and habitats providing opportunities forrecreational and cultural activitiesLowMediumHighHighHighLowHigh4.3 Raw materialsThere is no recorded use of building materials (e.g. reeds, sand) gathered from the <strong>Uilkraals</strong>Estuary for subsistence of commercial purposes. The lack of subsistence use is unsurprisingbecause of the population make‐up and the lack of traditional dwellings in this catchment.4.4 Carbon sequestrationCarbon sequestration is measured in terms of the net storage or loss of carbon that takes placeas a result of a long‐term increase or decrease in biomass. The contribution made by estuariesto carbon sequestration is largely unknown, and was thought unlikely to be significant apartfrom in mangrove systems. However recent studies have found estuarine wetlands are able tosequester carbon at ten times the rate of any other wetland ecosystem due to the high soilcarbon content and burial due to sea level rise (Brigham et al. 2006). Therefore higher rates ofcarbon sequestration and lower methane emissions in marsh areas, such as those identified inthe <strong>Uilkraals</strong> by Mucina et al. (2003) have the potential to be valuable carbon sinks.Nevertheless, the area is not extensive and the overall value is not likely to be significant inisolation, but only inasmuch as it contributes cumulatively to this service provided byecosystems in general.<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>35<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>

4.5 Waste treatmentWaste treatment is likely to be an important ecological service provided by the aquaticecosystems of the <strong>Uilkraals</strong> catchment, particularly in that agricultural return flows are dilutedand assimilated by the system. The value of this function is usually estimated in terms of thecost savings of treating the water before it is released. However, the quantity of pollutantsreleased into the system is unknown. It is important to note that the value of the system isonly measured in terms of the amount assimilated by the system. This capacity could bereduced under certain circumstances, resulting in decreased water quality downstream andexacerbating the negative impacts on downstream users that would already be caused byincreased pollution loads due to agricultural expansion.In order to effectively quantify the value of the waste treatment services water qualityassessments would have to identify any periods of elevated loads, which would signify whenthe <strong>Uilkraals</strong> system was not able to assimilate and dilute agricultural return flows, which havethe capacity to deliver of organic pollutants into the estuary.The capacity to assimilate pollutants could also be reduced under certain circumstances,resulting in decreased water quality downstream and exacerbating the negative impacts ondownstream users that would already be caused by increased pollution loads due toagricultural expansion.4.6 Export of materials and nutrientsThe export of sediments and nutrients to the marine zone is an important function of someriver systems. For example, the prawn fisheries of KwaZulu‐Natal depend on such exports(DWAF 2004b). However, this function is far more important on the east coast, which isrelatively nutrient‐poor, than on the west coast, where the outputs of estuaries do notcompete with the nutrients supplied by the Atlantic upwelling systems (Turpie & Clark 2007).It is unlikely that the export of materials and nutrients is important in this system because itslow mean annual runoff (MAR).4.7 Refugia areas and nursery valueRefugia areas are areas that help to maintain populations in a broader area. For example,wetlands within relatively arid areas may play an important seasonal role in the maintenanceof wild herbivores that are utilised in tourism operations well beyond the wetland. This isprobably not important in the study area apart from for fish. In the rivers, some of the smallertributaries have become important as refuge areas for endemic fish, although their ability torepopulate the rest of the river system is low at present. In the estuary, some inshore marinefish populations may utilise the estuary as a warmer refuge during upwelling events (Lamberth2003). The extent of this function in its contribution to marine populations is unknown.<strong>Uilkraals</strong> Estuary <strong>Situation</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>36<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong>