Download PDF (2.5MB) - Anchor Environmental

Download PDF (2.5MB) - Anchor Environmental

Download PDF (2.5MB) - Anchor Environmental

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

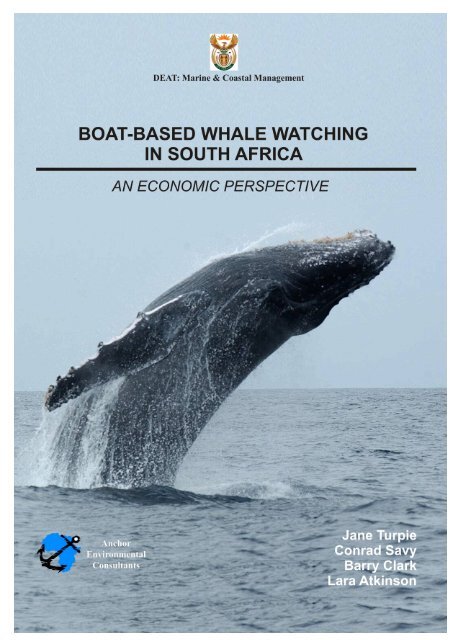

BOAT-BASED WHALE WATCHING<br />

IN SOUTH AFRICA:<br />

AN ECONOMIC PERSPECTIVE<br />

Jane Turpie, Conrad Savy, Barry Clark & Lara Atkinson<br />

<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Consultants, PO Box 34035, Rhodes Gift 7707<br />

With inputs from<br />

Tony Leiman 1 , Zyd Mzamo 1 , Leigh Lakay 1 ,<br />

Ken Findlay 2 , Peter Best 3 & Simon Elwen 4<br />

1 School of Economics, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7701<br />

2 Cetus Projects, 13 Norfolk Road, Lakeside 7945<br />

3 Iziko Museums of Cape Town<br />

4 Mammal Research Unit, University of Pretoria<br />

June 2005<br />

Cover Photo: Ken Findlay

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

<strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Consultants were commissioned by DEAT: Marine and Coastal Management<br />

to undertake a study of the boat-based whale watching industry in South Africa with a view to<br />

providing recommendations as to how to maximise the value of the industry. The aims of the study<br />

were to (1) describe the industry characteristics and activities, (2) determine profitability and reasons<br />

for success or failure, (3) estimate the value of the industry, (4) highlight potential for growth and (5)<br />

identify threats to growth.<br />

The study was based on a literature review of the industry worldwide, surveys of permitted and nonpermitted<br />

boat-based whale watching operators, and interviews with key informants in the tourism<br />

industry.<br />

Whale watching began as a commercial activity in 1955 in the USA, and spread rapidly around the<br />

world from the late 1980s. By 1998, the phenomenon had grown to 9 million whale watchers in 87<br />

countries or territories, with an estimated global expenditure of S$1049 million, of which $299 million<br />

was spent directly on whale watching tours. Most (72%) of this is boat-based, and land-based whale<br />

watching occurs mainly in ten countries, with South Africa being the top land-based whale watching<br />

destination. Boat-based whale watching is relatively recent in South Africa. Boat-based whale<br />

watching has become increasingly regulated around the world in order to minimise impacts on<br />

whales, and South Africa has among the most stringent regulations.<br />

Whale watching in South Africa forms part of a marine tourism industry which benefits from the high<br />

diversity and accessibility of cetaceans and other marine attractions such as seabirds, seals, the<br />

‘sardine run’ and coastal scenery. The whale watching aspect focuses on Southern Right, Humpback<br />

and Bryde’s whales. Southern Rights dominate whale watching along the Cape coast, where they<br />

spend the winter and spring (July – December). 90% of the visiting population occur within a mile of<br />

the coast, predominantly in sheltered bays. Humpback whales are seen on migration up and down<br />

the west and east coasts during May-June and October-December. Bryde’s whales are resident<br />

along the Cape coast, in relatively low densities.<br />

Boat-based whale watching began in South Africa in the early 1990s, and became legal for permit<br />

holders in 1998. Marine and Coastal Management administers permits and is responsible for policing<br />

the industry, except in KwaZulu-Natal, where KZN Wildlife takes responsibility for policing. Boatbased<br />

whale watching is still classified as an experimental fishery, with permits being short-term and<br />

renewable annually. The permit holders are represented by the South African Boat-based Whale<br />

Watching Association (SABBWWA). There are currently 25 areas for boat-based whale watching<br />

around the coast, with one permit per area in most cases (26 possible permits in total). Permits are<br />

for a single boat, and the fee is based on passenger capacity (currently R6400 plus R1860 per<br />

passenger).<br />

18 permits are currently allocated. Half of the permit holders are in the Western Cape, which has 14<br />

of the available permits and the highest proportion of permits that have been allocated. Some of the<br />

permits are very recently allocated, and had not begun operating at the time of study.<br />

Among the permit-holders, boat-based whale watching is largely an activity that adds value to a<br />

marine tourism business. Specialist operators were rare and did not do well. In addition, many of the<br />

marine tour businesses had links to other similar or complementary businesses (such as<br />

accommodation establishments). Most operators offered marine tours thoughout the year, with whale<br />

watching featuring during the whale season. Nevertheless, an average of 79% of income from the<br />

permitted boat was estimated to be generated by whale watching. The boat-based whale watching<br />

aspect of the business typically employs one or two individuals fulfilling the manager, skipper and<br />

guide roles, and sometimes an additional person for administrative and marketing aspects. In most<br />

cases this aspect of the business relies on one boat and one vehicle, plus a small office facility near<br />

the launch site. A few had specialised equipment such as hydrophones. Catamarans were most<br />

common, although a range of boat types were used, ranging from R115 000 to R5 million in value. A<br />

typical boat is 5-10 m, with a capacity of 10-20 passengers. Boat size was limited where operators<br />

had to launch from a beach or slipway, but larger boats (up to 50 passengers) occur in areas where<br />

moorings are available. There is a trade-off between passenger capacity and number of trips per day:<br />

most permit holders felt that a larger boat would improve their turnover, except for the very large boat

owners, who felt that a smaller, faster boat would allow more trips. Whale watching trips are typically<br />

two hours long, compared with other marine tours that typically last an hour.<br />

Peak demand for whale watching occurs from August to November, coinciding with the peak period<br />

for overseas visitors and the local September holiday period. However, whale watching is feasible as<br />

a year-round activity in some areas. Operators conduct up to 4 or 5 trips per day durng the main<br />

season. Numbers of trips, passengers and occupancy rates vary greatly between operators, and<br />

there were discrepancies between logbook and interview data. For operators that reported all trips,<br />

whale sightings occurred on 23-82% of trips, whereas those that just reported whale trips had<br />

sightings on 92-100% of trips. It was estimated that 26 000 passengers went on whale watching trips<br />

in 2004, of whom 86% were foreign.<br />

With prices per trip ranging from R150 – R650 (average R400), total turnover was estimated to be in<br />

the order of R12.8 mililon. Most permit holders generate over R200 000 from whale watching trips<br />

alone. Based on costs attributed to the boat-based whale watching aspect of the business, this<br />

activity was estimated to be profitable for two-thirds of permit holders. The non-profitable businesses<br />

were not operating at full capacity for various reasons. About half of turnover is profit. The success of<br />

different permit holders was not significantly related to frequency of whale sightings, but there was a<br />

strong relationship between the degree of investment in marketing and business turnover. High<br />

profits were also generally recorded for operations with medium sized boats (16 – 30 passengers).<br />

Other factors that probably influenced success included the capability of permit hodlers, the location,<br />

e.g. in relation to tourist centres, and competition from other locations or operators, including nonpermitted<br />

operators in the same area.<br />

Boat-based whale watching is estimated to generate about R45 million in tourism expenditure in<br />

South Africa, contributing some R37 million to Gross Domestic Product. Strictly speaking, the<br />

economic impact of boat-based whale watching is the expenditure that would not have occurred in the<br />

absence of the industry. It is difficult to assess the degree to which this is the case without carrying<br />

out a survey of whale watchers. For the industry to have a really significant impact, boat-based whale<br />

watching has to become a sufficiently significant component in the variety of attractions offered by<br />

South Africa to swing tourists’ decisions about where to go on vacation. In other words, it has to be<br />

competitive on a global scale.<br />

In addition to permitted activity, there is considerable activity by non-permitted operators. The<br />

permitted and non-permitted activities together provide a reasonable picture of the variation of<br />

demand around the coast. This variation, in relation to numbers of permits currently on offer, can help<br />

inform future management of the industry, such as where to concentrate activity. Four types of<br />

operators were identified, with estimates of their numbers as follows:<br />

Possible Permit<br />

Non-permitted operators<br />

permits holders Dedicated Incidental Opportunistic<br />

West coast 3 1 1 3-5 2-4<br />

Cape Metro 3 4 1 4 <br />

Agulhas Coast 5 5<br />

Garden Route 4 4 1 1 2<br />

Sunshine Coast 2 1 3<br />

Border Kei 1 0 2<br />

Wild Coast 2 1<br />

Hibiscus Coast 2 1 1 3 5-6<br />

Durban/Dolphin Coast 1 0 1 3-4<br />

Zululand 1 0<br />

Maputaland 2 1 2 4 2<br />

There is no rigorous way of quantifying future potential of an industry. Assumptions have to be made<br />

on the basis of the factors perceived to be important to the success of businesses in the industry.<br />

The magnitude and future changes of these factors themselves often have to be estimated based on<br />

expert opinion. This is certainly the case with boat-based whale watching. Future potential can be<br />

assessed by examining the natural resources that contribute to the attractiveness of the service<br />

offered, current occupancy levels and surplus capacity (taking cognisance of the influence of different

usiness characteristics and unrelated reasons for failure), the pre-existing tourist market and<br />

accessibility and the constraints such as sea and launching conditions. We take these factors into<br />

consideration in estimating the potential number of permits required in each area in order to maximise<br />

industry potential.<br />

Boat-based whale watching has grown steadily from 1999 to 2003, with numbers of passengers<br />

remaining stable from 2003 to 2004, possibly due in part to the strengthening of the rand. Based on<br />

possible seagoing days during whale season, it is estimated that the permitted boats are only<br />

operating at about one third of their potential capacity. Some of this is due to certain boats that have<br />

not yet begun operations, and others that are experiencing difficulties. The degree of non-permitted<br />

activity suggests that the demand exists to take advantage of this spare capacity to some extent.<br />

Taking the marketability of the resource base into account (the quality of whale watching), the<br />

limitations imposed by sea conditions, and the existing demand as described by operators and<br />

tourism agents, different parts of the coast were rated from poor to excellent in terms of their whale<br />

watching potential. Based on existing demand, rather than potential demand that could be generated<br />

by additional marketing, it is estimated that the coast could already support at least six additional<br />

permits in some of the better areas. Note that current demand is a function of successful marketing<br />

efforts by existing permit holders as well as regional tourism bodies. Taking untapped existing<br />

markets into account, this could potentially increase to 11 additional permits. Demand could<br />

potentially be increased in a number of other areas by marketing, although permit numbers will<br />

ultimately be restricted by sustainability issues. Indeed, the decision on where to expand boat-based<br />

whale watching activities in future should ultimately be decided on the basis of marketing strategy<br />

(e.g. concentrating activity into high quality whale watching areas) and what the resource can<br />

withstand, rather than where current demand exists. In the poor areas, where few of the possible<br />

permits have been taken up, the activity may not be viable at present.<br />

The increased number of permits should be seen as synonymous with an expansion in the number of<br />

boats (i.e. each permit is for one boat). There is no economic reason for this to mean that the<br />

additional permits should not go to existing permit holders. Indeed, multiple users working in the<br />

same area would be expected to compete, which would create greater pressure on the resource,<br />

whereas a single owner of multiple permits would have more of an incentive to protect the resource.<br />

Moreover, allowing existing permit holders to have additional permitted boats rewards these operators<br />

instead of penalising them by providing new permits to other operators in areas where they have<br />

created demand.<br />

In order to maximise the industry potential and minimise the obstacles to growth, the main<br />

recommendations made with regard to its management by MCM are as follows:<br />

• MCM and SABBWWA should enter into a co-management arrangement whereby SABBWWA<br />

participates in permit allocation, law enforcement and performance assessment of permit holders;<br />

• Communication should be streamlined through a dedicated liaison person from each organisation;<br />

• The number of available permits should be increased in areas with high potential, subject to<br />

environmental impact assessment, and reviewed on a regular basis;<br />

• Allocation of permits should be based on a systematic set of criteria and weightings which include<br />

indications of capability and likely success, black empowerment and quality of service;<br />

• Permits should confer long-term rights, subject to annual payments and performance assessments<br />

which check activity, compliance, monitoring and standards of service; and<br />

• Permit fees should be used towards effective policing, data analysis, communication and research.

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

1. INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................1<br />

2. STUDY APPROACH AND METHODS..................................................................................2<br />

2.1 Overall approach...................................................................................................................2<br />

2.2 Consultation with management authorities and industry.........................................................2<br />

2.3 Review..................................................................................................................................2<br />

2.4 Questionnaire surveys and data collection.............................................................................2<br />

2.5 Assessment of industry potential ...........................................................................................4<br />

2.6 Capacity building...................................................................................................................4<br />

3. WHALE WATCHING: AN INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVE...............................................5<br />

3.1 General overview ..................................................................................................................5<br />

3.2 South Africa in perspective....................................................................................................9<br />

4. THE RESOURCE AND MANAGEMENT OF BOAT-BASED WHALE WATCHING IN SOUTH<br />

AFRICA...........................................................................................................................................12<br />

4.1 The whale resource.............................................................................................................12<br />

4.2 Management of boat-based whale watching ........................................................................13<br />

4.3 Designated boat-based whale watching areas .....................................................................14<br />

4.4 Permit charges....................................................................................................................16<br />

5. PERMIT-HOLDER CHARACTERISTICS, SUCCESS AND ECONOMIC CONTRIBUTION .17<br />

5.1 Sensitivity and availability of information..............................................................................17<br />

5.2 Distribution and history of permit holders .............................................................................17<br />

5.3 Business characteristics......................................................................................................18<br />

5.4 Employment........................................................................................................................19<br />

5.5 Equipment and infrastructure...............................................................................................19<br />

5.6 Boat characteristics, current and optimal capacity................................................................20<br />

5.7 Use of permitted boats ........................................................................................................22<br />

5.8 Trip characteristics ..............................................................................................................22<br />

5.9 Seasonality, number of trips and passengers.......................................................................22<br />

5.10 Prices and turnover.........................................................................................................26<br />

5.11 Operating costs and profitability ......................................................................................28<br />

5.12 What determines success .............................................................................................29<br />

5.13 Contribution to the economy............................................................................................31<br />

6. BBWW ACTIVITY AND DEMAND AROUND THE COAST .................................................34<br />

6.1 Introduction .........................................................................................................................34<br />

6.2 Western Cape .....................................................................................................................35<br />

6.2.1 West Coast (Areas 1-3; Permits: 1 of 3) ......................................................................36<br />

6.2.2 Cape Metro (Areas 4-6; Permits: 4 of 3) ......................................................................38<br />

6.2.3 Agulhas Coast (Area 7-11; Permits: 5 of 5)..................................................................40<br />

6.2.4 Garden Route (Area 12-14; Permits: 4 of 4) ................................................................42<br />

6.3 Eastern Cape ......................................................................................................................44<br />

6.3.1 Sunshine Coast (Areas 15-16; Permits: 1 of 2)............................................................44<br />

6.3.2 Border Kei Region (Area 17; Permits: 0 of 1)...............................................................46<br />

6.3.3 Wild Coast Region (Areas 18-19; Permits: 1 of 2)........................................................47<br />

6.4 KwaZulu-Natal.....................................................................................................................49<br />

6.4.1 Hibiscus Coast (Area 20-21; Permits: 1 of 2)...............................................................49<br />

6.4.2 Durban Metro and Dolphin Coast (Area 22; Permits: 0 of 1) ........................................51<br />

6.4.3 Zululand (Area 23; Permits: 0 of 1)..............................................................................53<br />

6.4.4 Maputaland (Area 24-25; Permits: 1 of 2)....................................................................53<br />

6.5 Summary of legal and illegal activity ....................................................................................57<br />

7. FUTURE POTENTIAL OF THE INDUSTRY ........................................................................59<br />

7.1 Past growth of the industry ..................................................................................................59<br />

7.2 Current capacity and demand..............................................................................................60<br />

7.3 Marketability of the resource base .......................................................................................61<br />

7.4 Estimated potential of different areas...................................................................................62<br />

7.5 The importance of standards and marketing ........................................................................68<br />

7.6 Sustainability limits..............................................................................................................68<br />

8. CONCLUSIONS AND MANAGEMENT RECOMMENDATIONS..........................................70<br />

8.1 Introduction .........................................................................................................................70<br />

8.2 Numbers of permits.............................................................................................................70

8.3 The permit system, conditions and incentives......................................................................71<br />

8.4 Compliance, awareness and monitoring ..............................................................................72<br />

8.5 Co-management .................................................................................................................73<br />

8.6 Distributional issues ............................................................................................................73<br />

8.7 Specific recommendations...................................................................................................74<br />

9. REFERENCES....................................................................................................................76<br />

10. APPENDIX 1. TOURISM INFORMATION OFFICES CONTACTED....................................78<br />

11. APPENDIX 2. SUMMARY OF COMMERCIAL WHALE WATCHING AROUND THE WORLD<br />

...........................................................................................................................................79<br />

11.1 North America.................................................................................................................79<br />

11.1.1 United States of America.............................................................................................79<br />

11.1.2 Canada.......................................................................................................................79<br />

11.1.3 Mexico........................................................................................................................80<br />

11.2 Africa (other than South Africa) .......................................................................................81<br />

11.2.1 Canary Islands (Spain)................................................................................................81<br />

11.2.2 Namibia ......................................................................................................................81<br />

11.2.3 Mozambique ...............................................................................................................82<br />

11.2.4 Madagascar................................................................................................................82<br />

11.3 Australasia......................................................................................................................82<br />

11.3.1 Australia .....................................................................................................................82<br />

11.3.2 New Zealand...............................................................................................................84<br />

11.3.3 Tonga .........................................................................................................................85<br />

11.3.4 Antarctica....................................................................................................................86<br />

11.4 Europe............................................................................................................................86<br />

11.4.1 Norway .......................................................................................................................86<br />

11.4.2 Iceland........................................................................................................................86<br />

11.4.3 Greenland (self-governing territory of Denmark)..........................................................87<br />

11.4.4 United Kingdom ..........................................................................................................87<br />

11.4.5 Ireland ........................................................................................................................88<br />

11.4.6 Spain (not including Canary Islands) ...........................................................................88<br />

11.4.7 Azores Islands (Portugal)............................................................................................88<br />

11.5 South America ................................................................................................................89<br />

11.5.1 Ecuador ......................................................................................................................89<br />

11.5.2 Brazil ..........................................................................................................................89<br />

11.5.3 Argentina ....................................................................................................................89<br />

11.6 Central America and West Indies ....................................................................................90<br />

11.6.1 Bahamas ....................................................................................................................90<br />

11.6.2 Turks & Caicos Islands ...............................................................................................90<br />

11.6.3 Dominican Republic ....................................................................................................90<br />

11.6.4 St Lucia ......................................................................................................................91<br />

11.7 Asia ................................................................................................................................91<br />

11.7.1 Oman..........................................................................................................................91<br />

11.7.2 Japan .........................................................................................................................91<br />

11.7.3 Taiwan........................................................................................................................92<br />

12. APPENDIX 3: NOTIFICATION OF PERMTS (1998)............................................................93<br />

13. APPENDIX 4: NOTIFICATION OF PERMITS (2002)...........................................................96<br />

14. APPENDIX 5: ASSESSMENT OF THE QUALITY OF THE WHALE RESOURCE............. 102<br />

15. APPENDIX 6. STATUS OF BOAT-BASED WHALE WATCHING IN SOUTH AFRICA –<br />

STATEMENT BY SABBWWA, JANUARY 2005............................................................................ 104

1. INTRODUCTION<br />

The whale watching industry has undergone significant growth over the last ten years, associated with<br />

the massive recovery of Southern Right and Humpback Whale populations along the coast. Whale<br />

watching in South Africa started with land-based whale watching at Hermanus, and grew with the<br />

area’s reputation as having the among best land-based whale watching in the world. Increasing<br />

demand, as well as international trends, led to pressure for allowing boat-based whale watching,<br />

which became legal in South Africa in 1998.<br />

Prior research has indicated that land-based whale watching makes a major contribution to the South<br />

African economy through the expenditure of visitors (Findlay 1997), but little or no work has been<br />

carried out on the more-recently introduced phenomenon of boat-based whale watching in South<br />

Africa. Judging by global trends, the industry has the potential to make a sizeable economic<br />

contribution, provided that both the industry and the resource upon which it depends are managed<br />

with appropriate foresight.<br />

Up till now, the industry has been hampered by management problems and has not developed to its<br />

full potential. The Department of <strong>Environmental</strong> Affairs and Tourism: Branch Marine and Coastal<br />

Management (MCM) commissioned <strong>Anchor</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Consultants to conduct an independent<br />

study on the boat-based whale watching industry with a view to providing recommendations as to how<br />

to maximise the economic value of the industry. The industry has not been assessed previously and<br />

the results of this study will provide valuable information to guide management and development of<br />

the sector according to sound economic principles, in conjunction with supporting biological data.<br />

The aims of this study were:<br />

1. To describe the industry in terms of its characteristics and activities;<br />

2. To determine the profitability of licence holders in whale watching areas and identify reasons for<br />

their success or failure in this regard;<br />

3. To assess and quantify the overall value and economic impact of the industry as it currently<br />

exists;<br />

4. To highlight potential for future economic growth and provide recommendations on how to<br />

maximise economic benefits; and<br />

5. To identify threats to growth which prevent the maximisation of economic benefits and provide<br />

recommendations on how to reduce these.<br />

1

2. STUDY APPROACH AND METHODS<br />

2.1 Overall approach<br />

This study was based on an international literature review of boat-based whale watching, interviews<br />

with major stakeholders in the boat-based whale watching industry in South Africa, and logbook data<br />

submitted by boat-based whale watching permit holders to MCM as part of their permit requirements.<br />

Information on resource quality was also taken into consideration.<br />

2.2 Consultation with management authorities and industry<br />

The study began with a meeting the client (MCM) in Cape Town in November 2004, to discuss the<br />

characteristics of the industry and to identify key areas for focus that would result in relevant outputs<br />

according to their management and policy needs. MCM supplied data on permit-holder details.<br />

During client meetings and subsequent research, the researchers were made aware of the existence<br />

of the South African Boat-based Whale Watching Association (SABBWWA). After initial contact<br />

,concern was expressed by SABBWA that the study had been commissioned and the questionnaire<br />

had been developed without their knowledge or input. The study was delayed for a period until<br />

SABBWWA had given their inputs and were happy for the survey process to resume. Meetings were<br />

held between the project leaders and members of SABBWWA in Knysna in December 2004 and with<br />

the chairman in Cape Town in January 2005. An MCM representative was also present at the latter<br />

meeting. During these meetings, the perceptions and concerns of SABBWWA relating to the industry<br />

were discussed. This provided an important alternative and independent assessment of the current<br />

management and industry characteristics to that provided by the management authority.<br />

2.3 Review<br />

The first part of the study was to conduct a review of boat-based whale watching. This included a<br />

search for information on the boat-based whale watching industry in South Africa. The main output of<br />

this task was a review of the whale watching industry internationally, in order to set the South African<br />

industry within a larger context, in terms of the quality of resources, demand for whale watching and<br />

its economic value, as well as the way in which boat-based whale watching is managed<br />

internationally. The review also served to set a framework for understanding the industry and its<br />

potential for growth through a review of its establishment and growth in South Africa, the existence of<br />

supporting and enabling frameworks and a description of the existing patterns of management and<br />

control of the resources.<br />

2.4 Questionnaire surveys and data collection<br />

Following this, questionnaire instruments were developed for surveying permit-holders and nonpermitted<br />

operators. Clients could not be surveyed because the study had to be conducted out of<br />

whale watching season. The permit-holder questionnaire sought to acquire information on the nature<br />

of the businesses involved and services provided, limitations, levels of occupancy and capital and<br />

operating costs associated with whale watching (Box 2.1). It also elicited the operators’ perceptions<br />

of future trends in the industry and of management. Non-permitted operators interviewed included<br />

marine tour operators that illegally conducted boat-based whale watching tours to varying extents,<br />

and some that did not, but that could potentially. In addition to marine tour operators, interviews were<br />

also conducted with hotel owners in the Border-Kei area and on the Wild Coast.<br />

In total, 17 of the 18 existing permit holders granted the researchers time for interviews. Permit<br />

holders were identified through contact details and related information provided by MCM and<br />

SABBWWA. These interviews were conducted between December 2004 and March 2005, outside<br />

2

the main whale watching season. All but one of the interviews was conducted in person. Though<br />

relatively costly, this method allows for what is widely recognised as the most accurate collection of<br />

interview data. Furthermore, visiting each area facilitated the identification of related stakeholders,<br />

particularly non-permitted operators, and direct observation of infrastructure and conditions specific to<br />

each area. This allowed the researchers to develop the best possible assessment of the<br />

characteristics of each permitted area. Supplementary material, such as pamphlets and maps was<br />

also collected from the operators as well as from general tourism outlets.<br />

Concurrent with each of these site visits, an additional 29 non-permitted individuals were interviewed<br />

during this study. The majority of these were identified during investigation and research in the field<br />

and relied on information provided by permit holders, local tourism authorities and non-permitted<br />

operators themselves. Other sources of information including launch-site controllers, NSRI volunteers<br />

and tourism associations were used to add value and where necessary substantiate claims made<br />

during interviews. The majority of these were identified opportunistically by other stakeholders. The<br />

degree of animosity between many non-permitted and potential operators and permit holders also<br />

provided the opportunity for a certain amount of triangulation regarding some of the perceptions of<br />

different interviewees.<br />

Box 2.1. Outline of the permit-holder survey instrument<br />

Part One<br />

• Description of the nature of the business and how whale watching fits in<br />

• Years of operation<br />

• Boat capacity<br />

• Use of the licensed boat for whale watching versus other activities (%sea days & % income)<br />

• Seasonality of activities (graph), and seasonality of demand (description)<br />

• Typical trip, duration and area used<br />

• Maximum possible trips per day, days per year<br />

• Estimated actual days per year, and trips per day<br />

• Demand relative to supply of trips<br />

• Average occupancy on trips<br />

• Changes over time<br />

• Envisaged future trends<br />

• Opinion on optimal boat size<br />

• Value added by offering whale watching and by having a permit<br />

• Existence and names of other operators in the area<br />

• Their impact on the business – negative and/or positive<br />

• Main constraints to growth of the whale watching aspect of the business<br />

• How could management by MCM be improved<br />

Part Two<br />

• Tour prices and discounts<br />

• Breakdown of tourists by origin<br />

• Operating costs per trip<br />

• Details of boat and other capital employed in the business<br />

• Staffing and salaries<br />

• Overhead costs<br />

As noted above, the period for research and site visits occurred outside of the recognised boat-based<br />

whale watching season. As a result it was not possible to interview actual clients in order to assess<br />

the patterns of spending by whale watchers. Estimates of overall turnover related to the industry, in<br />

terms of multiplier effects and their larger economic contribution to the SA economy, were thus made<br />

on the basis of related regional and international studies.<br />

3

2.5 Assessment of industry potential<br />

A contact database of relevant stakeholders in the tourism sector was developed from various<br />

sources, including information from tourist information offices on the internet, printed materials such<br />

as pamphlets and personal referrals by other contacts. In total 28 tourism offices and were contacted<br />

during this survey (Appendix 1). Tourist offices were organised into three main levels ranging from<br />

provincial to regional and finally, where possible, local information offices. This spread allowed a<br />

relatively complete picture of the tourism demand in these areas to be developed. Information was<br />

collected in face-to-face or telephonic interviews with these relevant contacts and covered information<br />

on the level of existing demand and trends in demand for marine tours, including boat-based whale<br />

watching. Contacts were also asked as to their opinion on the number of operators which were<br />

feasible based on the current demand for boat-based whale watching. These results were used to<br />

categorise each whale watching area according to the existing demand for boat-based whale<br />

watching.<br />

The quality of the whale resource and other tourism attractions were also considered important to<br />

take into consideration in assessing the potential of the industry. Whale experts Dr Ken Findlay<br />

(Cetus Projects) and Dr Peter Best (Iziko Museums of Cape Town) were consulted in this regard, and<br />

asked to describe and rate different areas of the coast in terms of the probability of encountering<br />

different types of whales and the quality of whale viewing, based on available data.<br />

2.6 Capacity building<br />

Capacity building formed an important thrust of this study. Two previously disadvantaged postgraduate<br />

students from the University of Cape Town’s School of Economics, Mr Zyd Mzamo and Ms<br />

Leigh Lakay were engaged to provide assistance on aspects of the project. In addition, an MSc<br />

student, Mr. Simon Elwen, based at the Mammal Research Institute/Iziko Museum’s Whale Unit,<br />

assisted Dr Peter Best in the assessment of the resource quality and sightings frequency for whale<br />

species in the permitted areas.<br />

4

3. WHALE WATCHING: AN INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVE<br />

3.1 General overview<br />

Whale watching, as a commercial enterprise, started in 1955 in southern California, where it focussed<br />

on viewing the endangered grey whale migrations passing the coastline (Hoyt 2001, Garrod & Fennell<br />

2004). An estimated 10 000 whale watchers visited the first official public whale watch lookout during<br />

1955, with both numbers of whale watchers and whale viewing platforms increasing steadily up to the<br />

mid-1980’s (Hoyt 2001, Greenpeace 2001). In the 1980’s the discovery of populations of blue whales<br />

and Humpback Whales, as well as local small whale and dolphin populations off the coast of<br />

California, allowed the industry to expand beyond its original dependence on the seasonal migration<br />

route of grey whales (Hoyt 2001). The International Whaling Commission’s (IWC) moratorium on<br />

whaling in 1986 further encouraged whale watching as a non-consumptive, sustainable use of the<br />

resource, around the world (Woods-Ballard et al. 2003). Shortly thereafter, in the late 1980’s,<br />

commercial whale watching grew rapidly as it spread to Australia, New Zealand, Japan and the<br />

Canary Islands (Greenpeace 2001).<br />

The first published world-wide survey on the value, extent and prospects of whale watching was<br />

conducted by Hoyt (1992) during 1991 which reported that 31 countries and/or territories were<br />

involved in commercial whale watching, with the number of whale watchers totalling just over 4 million<br />

per year. This first global study estimated that total whale watching expenditures (the amount whale<br />

watchers spent on tours as well as travel, food, accommodation and souvenirs) were US$317.9<br />

million per annum, although only US$77 million of that was being spent directly on the cost of tours<br />

(Hoyt 2001). A follow-up study in 1994 showed a 10% increase in the number of global whale<br />

watchers to 5.4 million through 65 countries or territories, with an estimated total expenditure of<br />

US$504 million (direct costs on tours US$122 million). By 1998 international whale watching had<br />

grown to encompass over 9 million whale watchers (a growth of 12%) through 87 countries or<br />

territories, yielding a total estimated expenditure of US$1049 million (direct costs on tours US$299<br />

million, Hoyt 2001). On a global scale, whale watching has clearly grown into a major tourist activity,<br />

which is capable of bringing substantial socio-economic benefits to the many communities around the<br />

world in which it takes place (Garrod & Fennell 2004).<br />

The report by Hoyt (2001) is currently the most recent, comprehensive documentation on worldwide<br />

tourism numbers, expenditures and socio-economic benefits of whale watching. For each country or<br />

territory involved in some degree of commercial whale watching, Hoyt (2001) summarises the<br />

following information;<br />

• The overall tourism and economic background<br />

• An estimate of the number of annual whale watchers<br />

• How much they spend on whale watching activities<br />

• A socio-economic profile of whale watching tourists, operators and the community, and<br />

• A concise assessment of the status and future of whale watching<br />

A summary of activities in different whale watching countries is provided in Appendix 2. Once a<br />

country claims more than a million whale watchers in a year, it is considered to belong to the “million<br />

whale watch club” Hoyt (2001). In 1994, only the United States yielded more than a million whale<br />

watchers, however, in 1998, Canada and Canary Islands (Spain) also reported more than a million<br />

whale watchers. By 1998 both Australia and South Africa had recorded more than half a million<br />

whale-watchers, and were anticipated to have exceeded a million by 2000. The fastest growing<br />

whale watching country in the world between 1994 and 1998 was Taiwan, which grew from zero to 30<br />

000 whale watchers during this period and continued to grow through 2000. Iceland, Italy, Spain and<br />

South Africa were recorded as being the next fastest growing whale watching countries between 1994<br />

and 1998. There is some evidence from visitor surveys that the whale watching growth in Iceland<br />

may not have been as rapid if the country had resumed whaling. The fastest growing continent for<br />

whale watching is Africa with an average 53% annual increase between 1994 and 1998, followed by<br />

Central America and West Indies (47.4%). Subsequent to1998, the fastest growing whale watching<br />

country in the world was recorded to be St Lucia in the eastern Caribbean, which had an<br />

extraordinary annual increase of whale watchers between 1998 and 2000 of 685%. This has been<br />

partly attributed to the fact that whale watch tour operators in this area have begun to market their<br />

5

tours through the cruise ship industry and the first regional association of whale watch operators<br />

(Caribbean Whale Watch Association) was formed. During the past decade, whale watching has<br />

continued to expand in most countries where commercial whale watching has been established.<br />

The World Tourism Organisation (WTO) predicts that tourist arrivals will continue increasing by on<br />

average 3-4% annually beyond 2000. The annual rate of increase in whale watching between 1994<br />

and 1998 was 13.6% and is likely to continue growing at a faster rate than that of predicted world<br />

tourism growth rates. Even taking into account the recent reduction in world tourism, Hoyt (2001)<br />

conservatively estimates that during 2001 as many as 10.1 million people went whale watching.<br />

The most common form of whale watching is boat-based (72%) with a wide range of vessels being<br />

used for this purpose, including anything from kayaks to converted ferry ships. Land-based whale<br />

watching accounts for the remaining 28% of whale watching and is principally conducted in only 10<br />

countries. In order for land based whale watching to successfully occur, the land-sea interface must<br />

be of a specific terrain. High cliffs dropping off steeply into the ocean and locations where the edge of<br />

the continental shelf drops off fairly close to land, allows the whales to come close inshore thus<br />

facilitating good land-based whale watching. Commercial ventures in land-based whale watching are<br />

globally dominant in four countries namely, South Africa, Canada, Australia and United States. Less<br />

than 0.001% of all whale watching consists of aircraft tours.<br />

Of the 83 cetacean species world wide, most are observed to some degree in various whale watch<br />

programs. The most common focal species for whale watching industries are humpback, grey,<br />

northern and southern right, blue, minke, sperm, short-finned pilot whales, orcas and bottlenose<br />

dolphins. The blue and northern right whales are classified as endangered species while the<br />

humpback and southern right whales are considered vulnerable (IUCN Red Data Book).<br />

The interaction of whales and humans dates far back in history and whales have been a source of<br />

fascination for coastal communities through the ages, with their images being evident in paintings,<br />

coins and early writings (Orams 2002). Human interest in cetaceans has primarily been based on<br />

commercial gain as a source of products for human use. Almost every large whale species was<br />

hunted at some stage in history, resulting in severe depletion of their numbers. By the middle of the<br />

20th century some species were on the verge of extinction (Orams 2002). Perhaps as a result of their<br />

severe exploitation by humans, resulting in very low numbers and thus rarely been seen, in the past<br />

50 years an increasing sense of compassion and empathy for these animals has developed. Whales<br />

have become icon images for many environmental movements around the world. There are ongoing<br />

debates at cultural, economic, political and scientific levels regarding the future management of<br />

whales. Two opposing viewpoints emerge, one being that whales should be protected from any<br />

consumptive use and the other that whales should be hunted on a sustainable basis (Orams 2002).<br />

The International Whaling Commission (IWC), established in 1946, is the international agency<br />

charged with management of large whales and with providing for the “conservation, development and<br />

optimum utilization of whale resources”. On establishment, the IWC was anticipated to be prowhaling,<br />

however, in more recent times the conflict between pro-whaling and anti-whaling within the<br />

IWC has received much criticism from several government representatives. In recent decades, the<br />

rapid growth in the whale watching industry has placed an additional economic value on live whales<br />

(as opposed to dead whales) in that they have become a popular tourist attraction. The whale<br />

watching industry however, is dependant on large numbers of easily accessible whales, purely for<br />

viewing purposes, rather than for consumption. The requirements of the whale watching industry are<br />

in direct conflict with that of the more traditional whaling industry. Some countries have even<br />

managed to, thus far, sustain practises of both whaling and whale watching simultaneously (e.g.<br />

Norway and Japan) although the two industries take place in different locations around the coastline<br />

and target different species.<br />

With the dramatic global growth in the commercial whale watching industry, it is not surprising that<br />

there has developed an associated need for specific regulations or guidelines to regulate the industry<br />

and minimise the negative impact thereof on the marine life and environment. There are widespread<br />

concerns that this recreational activity, growing in popularity, may have serious negative impacts on<br />

the whales. Whale watching has the potential to inflict some significantly negative impacts on the<br />

animals, most obviously are those impacts which are associated with disturbance of the animals, due<br />

to the close approach of boats (Garrod & Fennell 2004). If cetaceans feel threatened by the proximity<br />

of humans, their typical response is to move away, either by diving or swimming to a different<br />

6

location. Most cetaceans spend the majority of their lives in the open ocean where whale watching is<br />

not viable, however, most species targeted by the industry come close to land during critical stages in<br />

their lives e.g. to feed, breed, calve or nurse their young. It is at these stages in their life cycles that<br />

the animals are most vulnerable and also most subjected to disturbance by whale watchers. There is<br />

concern that repeated, intensive disturbance may impact negatively on foraging and/or hunting,<br />

causing the animals to move away from rich feeding grounds and potential mates (Garrod & Fennell<br />

2004). There have been reports of vessels moving between mother and calf pairs, causing the calves<br />

to become separated from their food supply, stressed and in extreme cases, dying as a result of this<br />

disturbance. The most dramatic form of disturbance caused by whale watchers is when boats<br />

accidentally collide with whales causing physical injury and sometimes death of the whale.<br />

Considering some of the potential impacts of commercial whale watching on cetaceans, governments<br />

and non-governmental organisations around the world are increasingly acknowledging that some<br />

level of whale watching management is required (Garrod & Fennell 2004). What is less evident is the<br />

extent and type of management intervention that should be implemented. Some countries have<br />

imposed “command and control” regulations that have been legally declared and disregarding the law<br />

is considered a criminal offence, while others simply encourage tour operators and tourists to<br />

voluntarily adopt a more responsible approach to whale watching. Many countries have established<br />

semi-formal, voluntary guidelines or codes of conduct for whale watching activities.<br />

Carlson (2001) provides a comprehensive compilation of all the whale watching regulations and<br />

guidelines currently in place around the world and the reader is further referred to this document for<br />

specific details that are not mentioned in this report. Garrod and Fennell (2004) analysed 58 such<br />

codes of conduct from around the world and ultimately report that the voluntary guideline approach to<br />

whale watching is increasingly being accepted as the preferred means of management. Accreditation<br />

schemes (belonging to scientific and/or research linked organisations providing approval of the<br />

operations) are also being promoted for management of whale watching (Berrow 2003). Most<br />

countries or communities involved with whale watching have some regulations, including codes of<br />

conduct which are voluntary, but have some degree of legal enforcement in specific areas e.g. marine<br />

reserves or sensitive areas (Berrow 2003). Development of an internationally recognized voluntary<br />

code of conduct that will be universally accepted by the world’s whale watchers is unlikely due to the<br />

considerable diversity of whale watching operations around the world.<br />

The formal legislative approach to whale watching management has often resulted in a complex array<br />

of regulations where some aspects of different legislations are contradictory or overlap or where major<br />

gaps exist in others. This creates confusion and misunderstandings when attempting to interpret the<br />

different regulations intended for the whale watching industry (Garrod & Fennell 2004). The<br />

legislation has, in many cases, failed to keep up with the rapidly growing and relatively new whale<br />

watching industry, with growth occurring at a rate regulators failed to predict (Garrod & Fennell 2004).<br />

A further problem with legally prescriptive regulations of the industry is that they are often poorly or<br />

incompletely enforced, mostly due to many operators interacting with many highly mobile targets over<br />

a vast area of sea being difficult and expensive to manage.<br />

The informal management of the whale watching industry relies on voluntary implementation of codes<br />

of conduct that are enforced by ethical obligation and peer pressure (Garrod & Fennell 2004).<br />

Voluntary guidelines have the advantage of being relatively easy to introduce in a short space of time<br />

and can be used to regulate the industry while more formal national regulations are being created and<br />

introduced. Formal regulations constructed in this manner are considered to be based on experience<br />

gained and to incorporate local knowledge, resulting in a mix of formal and informal regulations,<br />

allowing authorities to modify aspects to local conditions while still maintaining a common set of basic<br />

principles (Garrod & Fennell 2004).<br />

In general, management of whale watching, in whatever form it occurs, is acknowledged to be<br />

necessary and at the broadest level should aim to minimise the environmental and ecological<br />

impacts, including the impacts on cetaceans, such as to allow long term benefits to both the whale<br />

watching industry and the ecosystem (Greenpeace 2001). The basic principles are:<br />

• Whale watching activity must allow cetaceans to continue whatever behaviour they are engaged in<br />

at the time of contact. Care should be taken to ensure that they are not disturbed or interrupted in<br />

their activities by the approaching vessel. This includes noise disturbance.<br />

7

• The goal of whale watching should not be interaction but rather observation of undisturbed<br />

cetacean behaviour. When cetaceans decide to interact with whale watchers, the cetaceans<br />

should always control the duration and nature of such interactions.<br />

• In the long term, whale watching should not lead to changes in cetacean behaviour or dynamics, a<br />

change in habitat use or a decline in reproductive success.<br />

The International Whaling Commission (IWC) has established general principles for whale watching to<br />

serve as a basic guideline to whale watching regulations or codes of conduct as a whole (see Box 1).<br />

Box 1. General Principles for Whale Watching<br />

The IWC Scientific Committee has agreed the following general guidelines for whale watching:<br />

(1) Manage the development of whale watching to minimise the risk of adverse impacts:<br />

(i) implement as appropriate measures to regulate platform numbers and size, activity, frequency and<br />

length of exposures in encounters with individuals and groups of whales;<br />

-management measures may include closed seasons or areas where required to provide additional<br />

protection;<br />

-ideally, undertake an early assessment of the numbers, distribution and other characteristics of the<br />

target population/s in the area;<br />

(ii) monitor the effectiveness of management provisions and modify them as required to accommodate<br />

new information<br />

(iii) where new whale watching operations are evolving, start cautiously, moderating activity until<br />

sufficient information is available on which to base any further development.<br />

(iv) implement scientific research and population monitoring and collection of information on operations,<br />

target cetaceans and possible impacts, including those on the acoustic environment, as an early<br />

(v)<br />

and integral component of management;<br />

develop training programs for operators and crew on the biology and behaviour of target species,<br />

whale watching operations, and the management provisions in effect;<br />

(vi) encourage the provision of accurate and informative material to whale watchers, to:<br />

-developed an informed and supportive public;<br />

-encourage development of realistic expectations of encounters and avoid disappointment and<br />

pressure for increasingly risky behaviour.<br />

(2) Design, maintain and operate platforms to minimize the risk of adverse effects on cetaceans, including<br />

disturbance from noise:<br />

• vessels, engines and other equipment should be designed, maintained, and operated during whale<br />

watching to reduce as far as practicable adverse impacts on the target species and their<br />

environment;<br />

• cetacean species may respond differently to low and high frequency sounds, relative sound intensity<br />

or rapid changes in sound;-vessel operators should be aware of the acoustic characteristics of the<br />

target species and of their vessel under operating conditions; particularly of the need to reduce as far<br />

as possible production of potentially disturbing sound;<br />

• vessel design and operation should minimize the risk of injury to cetaceans should contact occur, for<br />

example, shrouding of propellers can reduce both noise and risk of injury;<br />

• operators should be able to keep track of whales during an encounter.<br />

(3) Allow the cetaceans to control the nature and duration of ‘interactions’:<br />

• operators should have a sound understanding of the behaviour of the cetaceans and be aware of<br />

behavioural changes which may indicate disturbance;<br />

• in approaching or accompanying cetaceans, maximum platform speeds should be determined<br />

relative to that of the cetacean, and should not exceed it once on station;<br />

• use appropriate angles and distances of approach; species may react differently, and most existing<br />

guidelines preclude head-on approaches;<br />

• friendly whale behaviour should be welcomed, but not cultivated; do not instigate direct contact with a<br />

platform;<br />

• avoid sudden changes in speed, direction or noise;<br />

• do not alter platform speed or direction to counteract avoidance behaviour by cetaceans;<br />

• do not pursue, head off, or encircle cetaceans or cause groups to separate;<br />

• approaches to mother/calf pairs and solitary calves and juveniles should be undertaken with special<br />

care there may be an increased risk of disturbance to these animals, or risk of injury if vessels are<br />

approached by calves;<br />

• cetaceans should be able to detect a platform at all times;-while quiet operations are desirable,<br />

attempts to eliminate all noise may result in cetaceans being startled by a platform which has<br />

approached undetected; -rough seas may elevate background noise to levels at which vessels are<br />

less detectable.<br />

8

3.2 South Africa in perspective<br />

Boat-based whale watching regulations and the levels of activity and estimated expenditure for<br />

different countries around the world are summarised in Tables 3.1 - 3.3. Table 3.1 shows that South<br />

Africa has among the strictest regulations for boat-based whale watching in the world. It must be<br />

noted, nevertheless that Hoyt’s (2001) estimates are regarded as extremely rough.<br />

Table 3.1. Summary of regulations pertaining to boat-based whale watching in major whale watching<br />

countries (source: Hoyt 2001)<br />

Regulation/<br />

Guideline<br />

Permit<br />

required<br />

Caution<br />

-ary<br />

Zone<br />

Minimum<br />

distance<br />

from<br />

whale<br />

Limit #<br />

boats<br />

per<br />

whale<br />

(close)<br />

Limit<br />

time of<br />

encounter<br />

Angle of<br />

approach<br />

restriction<br />

Speed<br />

restriction<br />

Approach<br />

females<br />

with calf<br />

Closed<br />

areas<br />

USA No 2 miles 100 yds 1 30 min Yes 7 knots -<br />

Canada Yes 300 m 50 m 1 15 min Yes no - Yes<br />

wake<br />

Mexico Yes - 30 m 2 30 min Yes 4 knots - Yes<br />

Canary Yes 300 m 60 m 1 - Yes slow - -<br />

Islands<br />

South Africa Yes 300 m 50 m 1 20 min Yes no No Yes<br />

wake<br />

Madagascar No 800 m 300 m 1 30 min Yes slow - -<br />

Australia In some 300 m 100 m 1 No Yes no No Yes<br />

areas<br />

wake<br />

New<br />

Yes 300 m 50 m 1 - Yes no 200 m<br />

Zealand<br />

wake<br />

Tonga No 300 m 100 m 1 - Yes 4 knots - -<br />

Norway No 300 m 30 m 1 - - - - -<br />

Iceland No - 50 m 1 not too Yes idle - -<br />

long<br />

United No - 200 m - - Yes 5 knots Minimal -<br />

Kingdom<br />

Azores Yes 200 m 50 m 1 30 min Yes - 100 m -<br />

Islands<br />

Brazil Yes - 50 m - - - - - -<br />

Argentina Yes - 50 m 1 - - - No -<br />

Dominican Yes 400 m 50 m 2 15 min Yes no - -<br />

Rep.<br />

wake<br />

Oman No 300 m 50 m - - Yes no - -<br />

wake<br />

Japan No 200 m 50 m 3 60 min - slow 100 m -<br />

Table 3.2. Proportion of global proportion of expenditure and number of operators for top 5 countries<br />

based on Hoyt (2001) estimates.<br />

Rank Whale watchers Operators Total expenditure<br />

1 USA (48%) USA (268) USA (34%)<br />

2 Canada (12%) Canada (237) Canada (19%)<br />

3 Canary islands (11%) Australia (223) South Africa (7%)<br />

4 Australia (8%) New Zealand (50) Canary Islands (6%)<br />

5 South Africa (6%) Japan (45) Argentina (5.7%)<br />

9

Table 3.3. Numbers of whale watching visitors, operators and direct and total estimated expenditures for<br />

countries offering tours which include whales as an attraction, based on Hoyt (2001). Countries<br />

are ranked by direct expenditures on whale watching.<br />

Rank Country Start Whalewatchers<br />

Operators<br />

Direct<br />

expenditure<br />

(mill US $)*<br />

Total<br />

expenditure<br />

(mill US $)<br />

1 USA 1955 4,316,537 268 158.385 357.020<br />

2 Canada 1971 1,075,304 237 27.438 195.515<br />

3 Ecuador Early 1980’s 11,610 19.700 23.350<br />

4 Canary Islands Late 1980’s 1,000,000 17.770 62.195<br />

5 Antarctica 1980’s 2,503 18 15.348 16.600<br />

6 Australia Late 1960’s 734,962 223 11.869 56.196<br />

7 Mexico 1970 108,206 39 8.736 41.638<br />

8 New Zealand 1987 230,000 50 7.503 48.736<br />

9 Japan 1988 102,785 45 4.300 32.984<br />

10 Brazil Mid 1980’s 167,107 4.071 11.314<br />

11 Iceland 1991 30,330 12 2.958 6.470<br />

12 Bahamas Late 1970’s 1,800 10 2.700 2.970<br />

13 Dominican Republic 1986 22,284 22 2.307 5.200<br />

14 United Kingdom Mid 1980’s 121,125 42 1.884 8.231<br />

15 Argentina 1983 84,164 10 1.638 59.384<br />

16 Norway 1988 22,380 10 1.632 13.043<br />

17 Ireland 1986 177,600 2 1.322 7.119<br />

18 Indonesia 1991 41,000 1.281 4.551<br />

19 Taiwan 1997 30,000 13 1.223 4.280<br />

20 Greenland Early 1990’s 2,500 2 0.832 2.750<br />

21 Azores Islands 1989 9,500 6 0.582 3.370<br />

22 Spain Late 1980’s 31,500 21 0.550 1.925<br />

23 France 1983 750 13 0.411 0.512<br />

24 Oman 1996 4,700 6 0.320 0.500<br />

25 South Africa Early 1990’s 510,000 15 0.311 69.186<br />

26 Italy 1988 5,300 3 0.241 0.543<br />

27 Namibia 1998 7,000 3 0.216 0.756<br />

28 Chile Early 1990’s 3,300 0.194 0.679<br />

29 Greece Late 1980’s 3,678 3 0.140 0.261<br />

30 Dominica 1988 5,000 4 0.127 0.970<br />

31 Philippines 1991 12,000 1 0.121 0.927<br />

32 Madagascar 1988 4,000 12 0.120 0.774<br />

33 New Caledonia 1995 1,695 15 0.107 0.375<br />

34 Maldives 1998 30 1 0.100 0.149<br />

35 Mozambique Late 1990’s 500 0.100 0.150<br />

36 Costa Rica 1990 1,227 1 0.100 0.218<br />

37 Puerto Rico 1994 92,500 1 0.096 0.650<br />

38 Grenada 1993 1,800 1.5 0.090 0.270<br />

39 Peru 1985 531 1 0.064 0.081<br />

40 Tonga 1994 2,334 4 0.055 0.422<br />

41 Turks and Caicos Early 1990’s 1,500 2 0.043 0.150<br />

42 St Vincent + Gren. Late 1980’s 600 3 0.034 0.100<br />

43 St Pierre & Miquelon 1993 607 1 0.016 0.094<br />

44 Bermuda 1981 180 3 0.013 0.020<br />

45 Guadeloupe & isl. 1994 400 3 0.013 0.023<br />

46 St Lucia 1997 65 2 0.005 0.008<br />

47 British Virgin Islands Late 1980’s 200 0.004 0.014<br />

48 US Virgin Islands 1991 75 2 0.004 0.008<br />

49 Niue 1994 50 3 0.002 0.002<br />

10

Table 3.3 excludes countries where current activity was regarded by Hoyt (2001) as minimal but which<br />

are just beginning to develop their own whale watching sector or where only dolphin-watching was<br />

offered. Note that where detailed data were available on expenditure (n=6), the boat-based element of<br />

these expenditure estimates were significant (percentage of overall expenditure: 98-100%; of direct<br />

expenditure: 84-100%). On average, 90% of all whale-watchers were boat-based in the 6 countries<br />

for which data were available, ranging from 59-100% of all whale watchers. All data are based on the<br />

year 1998. In 1998 South Africa ranked 25 th in terms of direct expenditure on whale watching.<br />

Over half (53%) of direct expenditures and 34% of total expenditures are accounted for by the United<br />

States alone, which has offered whale watching since the 1950’s. The next largest is Canada which<br />

accounts for just 9% of direct and 19% of total global expenditures by whale watchers. These<br />

countries also support the largest number of operators of any whale watching country. In comparison,<br />

South Africa accounted for only 0.1% of direct expenditures but 7% in total expenditures and 6% of all<br />

whale-watchers, placing it in the top 5 countries for these latter two characteristics (Table 3.2). The<br />

high ranking is probably a result of the importance of land-based viewing in South Africa. This<br />

indicates that South Africa may be in a prime position to add significant value to its whale-based<br />

tourism sector through the development of a boat-based element in this sector and an increase in<br />

direct spending on whale watching. It is also important to note that these figures were calculated in<br />

the period prior to the establishment and subsequent growth in South Africa’s boat-based whale<br />

watching sector where only 4 permit holders were recorded by MCM in 1999 (compared to the current<br />

total of 18 permit holders in 2004). Hoyt (2001) however records a total of 15 operators, with 14 of<br />

these described as being active. South Africa’s ranking could thus have risen substantially during the<br />

intervening period.<br />

11

4. THE RESOURCE AND MANAGEMENT OF BOAT-BASED<br />

WHALE WATCHING IN SOUTH AFRICA<br />

4.1 The whale resource<br />

South Africa supports a relatively high cetacean diversity, with over 19 species having been recorded<br />

in southern African waters (Stuart and Stuart 1988). Only 5 cetacean species, including 3 baleen<br />

whale species are, however, sighted regularly enough to support any kind of whale watching tourism<br />

(Apps 1996, Table 4.1). The two main targets for whale-watchers are undoubtedly the Southern Right<br />

and Humpback whales which occur regularly off the coast during winter and spring seasons (Apps<br />

1996). A third species, Bryde’s whale is also regularly encountered and appears to have some<br />

populations resident along the western and southern coast (Apps 1996).<br />

Table 4.1. Common cetacean species sighted regularly in Southern African waters<br />

Common name Species Occurrence<br />

Baleen Whales (Suborder Mysticeti)<br />

Southern Right Whale Eubalaena australis Migrant in winter<br />

Humpback Whale Megaptera novaeangliae Migrant in winter<br />

Bryde’s Whale Balaenoptera edenii Resident<br />

Dolphins or Toothed Whales (Suborder Odontoceti)<br />

Bottlenose Dolphin Tursiops truncatus Resident<br />

Common Dolphin Delphinus delphis Resident<br />

Dusky Dolphin Lagenorhynchus obscurus Resident<br />

Heaviside’s Dolphin Cephalorynchus heavisidii Resident<br />

Humpback Dolphin Sousa plumbea Resident<br />

The Southern Right Whale populations of South Africa are the most well-known whale watching<br />

attractions in the country. This species supports a thriving whale-viewing industry, including one of<br />

the most valuable land-based viewing tourism, largely around the Western Cape (Findlay 1997).<br />

Populations migrate to the South African coastline each winter in order to mate and calve, with a<br />

significant proportion of females, over 90%, returning to have their first calf (Best 2000). Their<br />

distribution, though discontinuous, is highly predictable (Elwen & Best 2004a). Research into returns<br />

and movement patterns in season suggest however, that they are not site specific, indicating instead<br />

that the individuals along the South African coast appear to contribute to one homogenous population<br />

(Best 2000). Although they are generally common along the south-western coastline between<br />

Lambert’s Bay and Algoa Bay, sightings have been recorded as far east as St Lucia (Apps 1996,<br />

MCM unpubl. data). During the season, about 90% of Southern Right Whales occur within one<br />

nautical mile of the coast. They tend to concentrate in large sheltered bays, with the highest densities<br />

occurring between Arniston and Puntjie (on the Duiwenhoks estuary which includes De Hoop Marine<br />

Reserve). Other major concentrations occur at Mossel Bay, Struis Baai, Pearly Beach, Walker Bay,<br />

Kleinmond and to a lesser extent, False Bay. On the West Coast, concentrations occur at Yzerfontein<br />

and St Helena, but these are at much lower densities than on the southern coast. The whales are<br />

thought to move around to the west coast during periods of prolonged south-easterly winds, possibly<br />

due to poor sea conditions on the south coast and imminent upwelling on the west coast (K. Findlay,<br />

pers. comm.). Southern Rights are interesting from a boat-based whale watching perspective in that<br />

they are boat-attracted, slow moving and exhibit a high level of surface activity including ‘spy –<br />

hopping’ between boat propellers.<br />

Humpback whales occur off the South African coast predominantly in mid-winter months and spring<br />

(Best et al. 1998). They mainly occur on migration between their Antarctic feeding grounds and their<br />

subtropical breeding grounds in warm waters of over 24ºC located in Mozambique and Madagascar<br />

on the east coast and northern Namibia, Angola and possibly Gabon on the west coast (Apps 1996).<br />

Their migration routes come near to the African coast along the west coast and Wild Coast regions,<br />

with relatively little activity in the southerly parts of the country (Best et al. 1998). On the West Coast,<br />

Humpbacks are most common moving northwards in May-June and returning southward in October to<br />

December. However, it appears that some individuals delay southward migration, remaining on the<br />

12

west coast up to February or March (Best et al. 1995). On the east coast, the whales are most<br />

common in May-June and in October-November. Individuals seen along the South African coast are<br />

thus generally moving to and from these areas and are not as easily approached or sighted as<br />

Southern Right Whales. Whales on migration commonly move at about 5km/h, though it is possible<br />

to find more static groups displaying interesting surface activity (K. Findlay, pers. comm.). The whales<br />

tend to come through in loose aggregations, so that sighting rates vary widely and can approach 100<br />

on a single trip. Findlay & Best (1996) estimated the population of this species migrating along the<br />

northern KwaZulu-Natal coast to be at least 1700 individuals in 1991. More recent estimates suggest<br />

that the east coast breeding population has recovered to over 6000 animals, with rates of increase in<br />

the order of 8 – 10%, and the population is now thought to be close to 70% of its carrying capacity (K.<br />

Findlay, pers. comm.). The species has been protected since 1963.<br />