A fair chance - United Nations Girls' Education Initiative

A fair chance - United Nations Girls' Education Initiative

A fair chance - United Nations Girls' Education Initiative

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

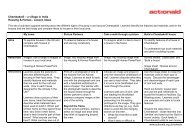

than 20 percentage points) in 15 countries includingEthiopia, Pakistan, and Nepal. There are another 14countries where it is between 10 and 20 percentagepoints, which include Cambodia, India, and Mali.Nearly half of the 29 countries where the GER gendergap was more than 10 percentage points are inFrench-speaking Africa. These countries are very poorand mainly rural, and repetition rates, especially inthe early grades of primary school, are very high.As discussed later, emphasis on achieving universalprimary education should not be allowed to disguisethe pressing importance of creating opportunities forgirls at post-primary level. Gender enrolmentinequality as measured by the gender parity index isconsiderably worse for secondary education (seeFigure 3). The Middle East and North Africa region isan important exception. It is worse still at universitiesand other higher education institutions. However, theabsolute GER gender gaps tend to be smaller at thesecondary level than at the primary level because theenrolment rates for secondary education as a wholeare lower, especially in the poorest countries. Table 2shows that there were 13 countries where this gap wasgreater than 10 percentage points in 1999/2000. Thisincludes India, Nepal and Pakistan. In contrast,relatively more females than males were attendingsecondary schools in Bangladesh.Data on intake rates is missing for quite a number ofcountries. However, countries without data are thesame group of French-speaking African countriesthat have the largest intake gender gaps (of over10 percentage points) as well as Ethiopia(30 percentage points), India (23), and Yemen (25)(see Annex 2 table 1).<strong>Education</strong>al attainmentData from household surveys shows far more clearlythan aggregate enrolments the devastating impactthat the education gender gap has on individual lives.<strong>Education</strong>al attainment statistics from Demographicand Health Surveys in over 30 countries show that avery high proportion of young women living in ruralareas have never been to school – nearly two-thirds inEthiopia and 28 per cent in India as recently as 1999.The gender gap among rural never-attenders is over10 percentage points for 17 out of the 23 countries inSub-Saharan Africa and in South and West Asia wherethis survey data is available (Annex 2 table 2). Thereare nine countries where such a large gender gap existswith respect to urban non-attenders. Figure 4 showsthe level of education attained by 15–19 year olds inthe nine case study countries from the latest surveys.There are enormous rural-urban disparities in femaleand male GERs in most countries. In Mali, forexample, the capital Bamako has a female primaryschool GER of 125 per cent compared with only 20 percent in remote regions such as Kidal and Mopti. Thefull attainment profiles for four of the case studycountries are presented in Figure 5. These show verystrikingly the size of the attainment gaps not onlybetween women and men, but also between the urbanand rural areas.Primary school completion rates are also very low inmany countries. This is especially the case for ruralwomen in much of French-speaking Africa and, amongthe case study countries in Ethiopia, Mali, Nepal, andPakistan. Barely one per cent of girls in their mid-lateteens, who were living in rural Ethiopia in 2000,finished the full eight-year primary school cycle. Thecompletion rate was only marginally better for rural boys(1.6 per cent). In India, fewer than half of rural females,but nearly two-thirds of rural boys, finished primaryschool in 1999. In contrast, in three countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (Malawi, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe),most of East Asia and the Pacific, Latin America, andthe Caribbean (including Brazil), completion ratesamong rural females are higher than for males.Grade 9 attainment data gives a good indication of therelative number of female and male children whomake the transition to secondary school. In a largemajority of developing countries, only a very smallpercentage of children reach even the lower grades ofsecondary school. In two-thirds of countries in11