A fair chance - United Nations Girls' Education Initiative

A fair chance - United Nations Girls' Education Initiative

A fair chance - United Nations Girls' Education Initiative

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

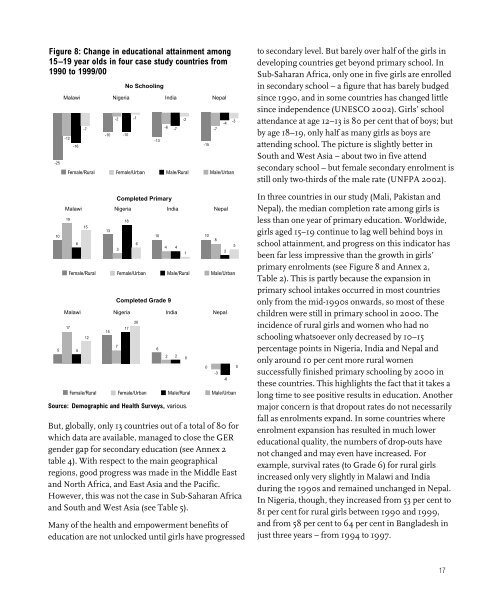

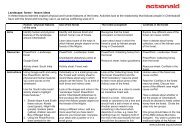

Figure 8: Change in educational attainment among15–19 year olds in four case study countries from1990 to 1999/00-2510Malawi Nigeria India Nepal-12-16Malawi Nigeria India Nepal19Malawi Nigeria India Nepal1765 5-71512-2 -1-10 -10131537No SchoolingFemale/Rural Female/Urban Male/Rural Male/Urban186But, globally, only 13 countries out of a total of 80 forwhich data are available, managed to close the GERgender gap for secondary education (see Annex 2table 4). With respect to the main geographicalregions, good progress was made in the Middle Eastand North Africa, and East Asia and the Pacific.However, this was not the case in Sub-Saharan Africaand South and West Asia (see Table 5).Many of the health and empowerment benefits ofeducation are not unlocked until girls have progressed-1310-6Completed Primary-74 4Female/Rural Female/Urban Male/Rural Male/UrbanCompleted Grade 9172062 2-210-1510-78-42-350 0-3-6Female/Rural Female/Urban Male/Rural Male/UrbanSource: Demographic and Health Surveys, various.to secondary level. But barely over half of the girls indeveloping countries get beyond primary school. InSub-Saharan Africa, only one in five girls are enrolledin secondary school – a figure that has barely budgedsince 1990, and in some countries has changed littlesince independence (UNESCO 2002). Girls’ schoolattendance at age 12–13 is 80 per cent that of boys; butby age 18–19, only half as many girls as boys areattending school. The picture is slightly better inSouth and West Asia – about two in five attendsecondary school – but female secondary enrolment isstill only two-thirds of the male rate (UNFPA 2002).In three countries in our study (Mali, Pakistan andNepal), the median completion rate among girls isless than one year of primary education. Worldwide,girls aged 15–19 continue to lag well behind boys inschool attainment, and progress on this indicator hasbeen far less impressive than the growth in girls’primary enrolments (see Figure 8 and Annex 2,Table 2). This is partly because the expansion inprimary school intakes occurred in most countriesonly from the mid-1990s onwards, so most of thesechildren were still in primary school in 2000. Theincidence of rural girls and women who had noschooling whatsoever only decreased by 10–15percentage points in Nigeria, India and Nepal andonly around 10 per cent more rural womensuccessfully finished primary schooling by 2000 inthese countries. This highlights the fact that it takes along time to see positive results in education. Anothermajor concern is that dropout rates do not necessarilyfall as enrolments expand. In some countries whereenrolment expansion has resulted in much lowereducational quality, the numbers of drop-outs havenot changed and may even have increased. Forexample, survival rates (to Grade 6) for rural girlsincreased only very slightly in Malawi and Indiaduring the 1990s and remained unchanged in Nepal.In Nigeria, though, they increased from 53 per cent to81 per cent for rural girls between 1990 and 1999,and from 58 per cent to 64 per cent in Bangladesh injust three years – from 1994 to 1997.17