A fair chance - United Nations Girls' Education Initiative

A fair chance - United Nations Girls' Education Initiative

A fair chance - United Nations Girls' Education Initiative

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

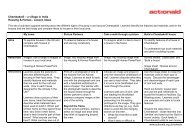

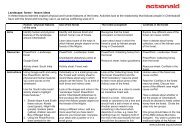

Box 9: Gender mainstreaming in DPEP, IndiaGirls’ education has been mainstreamed in the District Primary <strong>Education</strong> Project (DPEP) which is being implemented in 271districts in 15 states in India with strong backing by a consortium of donors. DPEP has adopted a two-pronged strategy,namely to make the education system more responsive to the needs and constraints of girls, and to create community demandfor girls’ education and facilitate enabling conditions for people’s participation. ‘The most important contribution of the genderand social equity-related work of DPEP is that it has succeeded in getting official recognition of, and support for, multiplestrategies necessary to reach out to the unreached.’ (India report).DPEP has not only outlined gender-related goals, it also provides a well-defined monitoring system with a mandate to functionas a catalyst, troubleshoot and provide specific inputs by way of training and resource support. At the national level, theNational Project Director has overall responsibility for ensuring that girls’ education objectives are mainstreamed in allparticipating states. External consultants help monitor and evaluate progress with respect to these goals. A GenderCoordinator has been appointed in each state. These coordinators meet every six months to review progress and makeconcrete recommendations. They identify low female literacy areas and constraints, review action plans made to promote girls’participation, organise conventions and awareness camps, facilitate the formation of mothers’ groups, and arrange to organisetraining for women to participate effectively in the newly created Village <strong>Education</strong> Committees. At the district level, a DistrictGender Coordinator is responsible for tracking girls’ participation. She is supported by gender focal points at the Block/Talukalevels. In some states, a District Resource Group provides this support.The primary work of Gender Coordinators is to sensitise the system to reach out and cater to the needs of girls in a nonjudgementaland gender-sensitive manner. Their activities include community mobilisation, organising escorts for girls,counseling parents, addressing girls’ work burdens, etc.The Village <strong>Education</strong> Committee (VEC) is the most important vehicle for increasing women’s participation and improving theenrolment and retention rates for girls. However, the representation of women on VECs varies enormously across the states.Source: India Reportcritical, when, in fact, demand factors tend to be moreimportant for girls. Another problem is thatpoliticians have found it easy to dismiss ‘gender’ as aforeign concept, partly because women’s groups, NGOsand other civil society members who could act aschampions for girls’ education, have been left ‘out ofthe loop’ in policy dialogue between governments anddonors. Similarly, in Pakistan and Nigeria it has been along uphill struggle to get politicians and policymakersto mainstream gender in major donor-supportededucation projects. A key factor behind recentprogress has been the co-option of gender advocatesfrom the NGO sector into influential policy-makingpositions in government, bringing with them not onlytheir own commitment but also their capacity to reachout to, and mobilise, wider civil society networks.Clearly there is no blueprint because these constraintsvary so much from one country to another. However,a balanced package addressing all aspects of genderinequalities in education is essential. Examples fromIndia and Malawi offer some possibilities (see Box 8and 9).Priority measuresGovernments and NGOs have adopted a range ofpolicies, programmes and projects in order toimprove girls’ education. The key measures that havebeen introduced in the case study countries aresummarised in Table 8. Comparative analysissuggests that within an integrated and comprehensivestrategy, the following interventions have beenespecially effective: free primary education, increasedincentives, more accessible schools, tackling sexualharassment and discrimination against pregnantpupils, developing a network of community schools,introducing bridging programmes to mainstreamnon-formal education, and promoting early childhoodeducation and care.32