BEECHER - NAWC

BEECHER - NAWC

BEECHER - NAWC

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

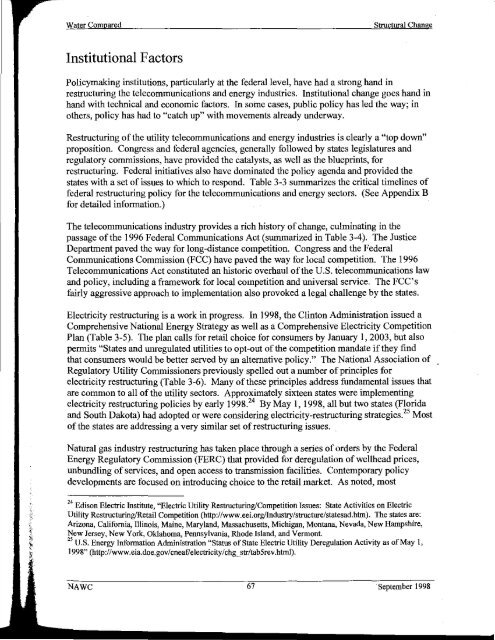

lWater Compared Structoral ChangeInstitutional FactorsPolicymaking institutions, particularly at the federal level, have had a strong hand inrestructuring the telecommunications and energy industries. Institutional change goes hand inhand with technical and economic factors. In soine cases, public policy has led the way; inothers, policy has had to "catch up" with movements already underway.Restructuring of the utility telecommunications and energy industries is clearly a "top down"proposition. Congress and federal agencies, generally followed by states legislatures andregulatory commissions, have provided the catalysts, as well as the blueprints, forrestructuring. Federal initiatives also have dominated the policy agenda and provided thestates with a set of issues to which to respond. Table 3-3 summarizes the critical timelines offederal restructuring policy for the telecommunications and energy sectors. (See Appendix Bfor detailed information.)The telecommunications industry provides a rich history of change, culminating in thepassage of the 1996 Federal Communications Act (summarized in Table 3-4). The JusticeDepartment paved the way for long-distance competition. Congress and the FederalCommunications Commission (FCC) have paved the way for local competition. The 1996Telecommunications Act constituted an historic overhaul of the U.S. telecommunications lawand policy, including a framework for local competition and universal service. The FCC'sfairly aggressive approach to implementation also provoked a legal challenge by the states.Electricity restructuring is a work in progress. In 1998, the Clinton Administration issued aComprehensive National Energy Strategy as well as a Comprehensive Electricity CompetitionPlan (Table 3-5). The plan calls for retail choice for consumers by January I, 2003, but alsopermits "States and unregulated utilities to opt-out of the competition mandate if they findthat consumers would be better served by an alternative policy." The National Association ofRegulatory Utility Commissioners previously spelled out a number of principles forelectricity restructuring (Table 3-6). Many of these principles address fundamental issues thatare common to all of the utility sectors. Approximately sixteen states were implementingelectricity restructuring policies by early 1998. 24 By May 1, 1998, all but two states (Floridaand South Dakota) had adopted or were considering electricity-restructuring strategies. 25 Mostof the states are addressing a very similar set of restructuring issues.Natural gas industry restructuring has taken place through a series of orders by the FederalEnergy Regulatory Commission (PERC) that provided for deregulation of wellhead prices,unbundling of services, and open access to transmission facilities. Contemporary policydevelopments are focused on introducing choice to the retail market. As noted, most24Edison Electric Institnte, "Electric Utility Restructuring/Competition Issues: State Activities on ElectricUtility Restructuring/Retail Competition (http://www.eei.orgilndustry/structore/statesad.htrn). The states are:'Arizona, California, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire,~-New Jersey, New York, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont.25U.S. Energy Information Administration "Status of State Electric Utility Deregulation Activity as of May I,1998" (http://www.eia.doe.gov /cneaf/electricity /chg__str/tab5rev.htrnl).<strong>NAWC</strong> 67 ·September I 998