Evaluating the “Good Death” Concept from Iranian Bereaved Family

Evaluating the “Good Death” Concept from Iranian Bereaved Family

Evaluating the “Good Death” Concept from Iranian Bereaved Family

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

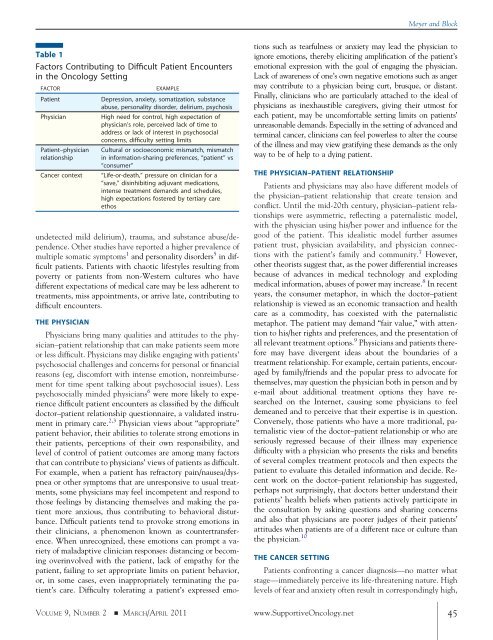

Table 1<br />

Factors Contributing to Difficult Patient Encounters<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Oncology Setting<br />

FACTOR EXAMPLE<br />

Patient Depression, anxiety, somatization, substance<br />

abuse, personality disorder, delirium, psychosis<br />

Physician High need for control, high expectation of<br />

physician’s role, perceived lack of time to<br />

address or lack of interest in psychosocial<br />

concerns, difficulty setting limits<br />

Patient–physician<br />

relationship<br />

Cultural or socioeconomic mismatch, mismatch<br />

in information-sharing preferences, “patient” vs<br />

“consumer”<br />

Cancer context “Life-or-death,” pressure on clinician for a<br />

“save,” disinhibiting adjuvant medications,<br />

intense treatment demands and schedules,<br />

high expectations fostered by tertiary care<br />

ethos<br />

undetected mild delirium), trauma, and substance abuse/dependence.<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r studies have reported a higher prevalence of<br />

multiple somatic symptoms 1 and personality disorders 5 in difficult<br />

patients. Patients with chaotic lifestyles resulting <strong>from</strong><br />

poverty or patients <strong>from</strong> non-Western cultures who have<br />

different expectations of medical care may be less adherent to<br />

treatments, miss appointments, or arrive late, contributing to<br />

difficult encounters.<br />

THE PHYSICIAN<br />

Physicians bring many qualities and attitudes to <strong>the</strong> physician–patient<br />

relationship that can make patients seem more<br />

or less difficult. Physicians may dislike engaging with patients’<br />

psychosocial challenges and concerns for personal or financial<br />

reasons (eg, discomfort with intense emotion, nonreimbursement<br />

for time spent talking about psychosocial issues). Less<br />

psychosocially minded physicians 6 were more likely to experience<br />

difficult patient encounters as classified by <strong>the</strong> difficult<br />

doctor–patient relationship questionnaire, a validated instrument<br />

in primary care. 2,3 Physician views about “appropriate”<br />

patient behavior, <strong>the</strong>ir abilities to tolerate strong emotions in<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir patients, perceptions of <strong>the</strong>ir own responsibility, and<br />

level of control of patient outcomes are among many factors<br />

that can contribute to physicians’ views of patients as difficult.<br />

For example, when a patient has refractory pain/nausea/dyspnea<br />

or o<strong>the</strong>r symptoms that are unresponsive to usual treatments,<br />

some physicians may feel incompetent and respond to<br />

those feelings by distancing <strong>the</strong>mselves and making <strong>the</strong> patient<br />

more anxious, thus contributing to behavioral disturbance.<br />

Difficult patients tend to provoke strong emotions in<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir clinicians, a phenomenon known as countertransference.<br />

When unrecognized, <strong>the</strong>se emotions can prompt a variety<br />

of maladaptive clinician responses: distancing or becoming<br />

overinvolved with <strong>the</strong> patient, lack of empathy for <strong>the</strong><br />

patient, failing to set appropriate limits on patient behavior,<br />

or, in some cases, even inappropriately terminating <strong>the</strong> patient’s<br />

care. Difficulty tolerating a patient’s expressed emo-<br />

Meyer and Block<br />

tions such as tearfulness or anxiety may lead <strong>the</strong> physician to<br />

ignore emotions, <strong>the</strong>reby eliciting amplification of <strong>the</strong> patient’s<br />

emotional expression with <strong>the</strong> goal of engaging <strong>the</strong> physician.<br />

Lack of awareness of one’s own negative emotions such as anger<br />

may contribute to a physician being curt, brusque, or distant.<br />

Finally, clinicians who are particularly attached to <strong>the</strong> ideal of<br />

physicians as inexhaustible caregivers, giving <strong>the</strong>ir utmost for<br />

each patient, may be uncomfortable setting limits on patients’<br />

unreasonable demands. Especially in <strong>the</strong> setting of advanced and<br />

terminal cancer, clinicians can feel powerless to alter <strong>the</strong> course<br />

of <strong>the</strong> illness and may view gratifying <strong>the</strong>se demands as <strong>the</strong> only<br />

way to be of help to a dying patient.<br />

THE PHYSICIAN–PATIENT RELATIONSHIP<br />

Patients and physicians may also have different models of<br />

<strong>the</strong> physician–patient relationship that create tension and<br />

conflict. Until <strong>the</strong> mid-20th century, physician–patient relationships<br />

were asymmetric, reflecting a paternalistic model,<br />

with <strong>the</strong> physician using his/her power and influence for <strong>the</strong><br />

good of <strong>the</strong> patient. This idealistic model fur<strong>the</strong>r assumes<br />

patient trust, physician availability, and physician connections<br />

with <strong>the</strong> patient’s family and community. 7 However,<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>orists suggest that, as <strong>the</strong> power differential increases<br />

because of advances in medical technology and exploding<br />

medical information, abuses of power may increase. 8 In recent<br />

years, <strong>the</strong> consumer metaphor, in which <strong>the</strong> doctor–patient<br />

relationship is viewed as an economic transaction and health<br />

care as a commodity, has coexisted with <strong>the</strong> paternalistic<br />

metaphor. The patient may demand “fair value,” with attention<br />

to his/her rights and preferences, and <strong>the</strong> presentation of<br />

all relevant treatment options. 9 Physicians and patients <strong>the</strong>refore<br />

may have divergent ideas about <strong>the</strong> boundaries of a<br />

treatment relationship. For example, certain patients, encouraged<br />

by family/friends and <strong>the</strong> popular press to advocate for<br />

<strong>the</strong>mselves, may question <strong>the</strong> physician both in person and by<br />

e-mail about additional treatment options <strong>the</strong>y have researched<br />

on <strong>the</strong> Internet, causing some physicians to feel<br />

demeaned and to perceive that <strong>the</strong>ir expertise is in question.<br />

Conversely, those patients who have a more traditional, paternalistic<br />

view of <strong>the</strong> doctor–patient relationship or who are<br />

seriously regressed because of <strong>the</strong>ir illness may experience<br />

difficulty with a physician who presents <strong>the</strong> risks and benefits<br />

of several complex treatment protocols and <strong>the</strong>n expects <strong>the</strong><br />

patient to evaluate this detailed information and decide. Recent<br />

work on <strong>the</strong> doctor–patient relationship has suggested,<br />

perhaps not surprisingly, that doctors better understand <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

patients’ health beliefs when patients actively participate in<br />

<strong>the</strong> consultation by asking questions and sharing concerns<br />

and also that physicians are poorer judges of <strong>the</strong>ir patients’<br />

attitudes when patients are of a different race or culture than<br />

<strong>the</strong> physician. 10<br />

THE CANCER SETTING<br />

Patients confronting a cancer diagnosis—no matter what<br />

stage—immediately perceive its life-threatening nature. High<br />

levels of fear and anxiety often result in correspondingly high,<br />

VOLUME 9, NUMBER 2 � MARCH/APRIL 2011 www.SupportiveOncology.net 45