Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Tom</strong> <strong>Thomson</strong><br />

Life & Work by David P. Silcox<br />

Although <strong>Thomson</strong> retains the basic shape of the pine in his oil sketch, he makes<br />

the foreground considerably brighter in the canvas. The water surface, which in the oil<br />

sketch is hastily laid in with a muddy grey and then a yellowish grey against the far<br />

shore, is transformed into long slabs of pigment in mauves, blues, and yellows—<br />

somewhat in the style of Lawren Harris (1885–1970) and J.E.H. MacDonald (1873–<br />

1932), both of whom excelled in laying down long, unbroken battens of paint one above<br />

the other.<br />

This dramatic change is especially evident in the sky. In the sketch,<br />

<strong>Thomson</strong> provides only a rapid swirl of nondescript character, deliberately leaving the<br />

wood surface exposed in several places—just as he does in the sketch for The West<br />

Wind. In the canvas, however, and even more emphatically than for the lake surface, he<br />

dresses the sky in wide, horizontal ribbons of paint. With subtle modulations from the<br />

yellow-green sunset clouds at the horizon through to the bluish arc that appears at the<br />

top of the painting, <strong>Thomson</strong> creates a perfect backdrop to the pine and its<br />

immediate foreground.<br />

The colour of the wood of the small panels has changed since it was milled almost<br />

a hundred years ago. When it was new, it was much lighter, possibly even a bright<br />

yellowish-white tone if it was of birch. The slow oxidizing over the years has turned the<br />

wood into a rich, honey-coloured element in the painting and given it a mellow patina.<br />

What is surprising is the immense variety in the colours <strong>Thomson</strong> summons up<br />

for The Jack Pine, an array not seen in the sketch: sumptuous hues, complementing<br />

and contrasting light and dark, near and far, minute and grand. Even the softening of the<br />

distant shoreline, compared with the harder treatment in The West Wind, takes The<br />

Jack Pine into that vivid yet dusky and indeterminate hour of the day that fascinated<br />

another great Canadian painter, J.W. Morrice (1865–1924), and clearly bewitched<br />

<strong>Thomson</strong> too. In the last winter of his short life, <strong>Thomson</strong> had figured out how to make<br />

truly great and durable art.<br />

After the Storm 1917<br />

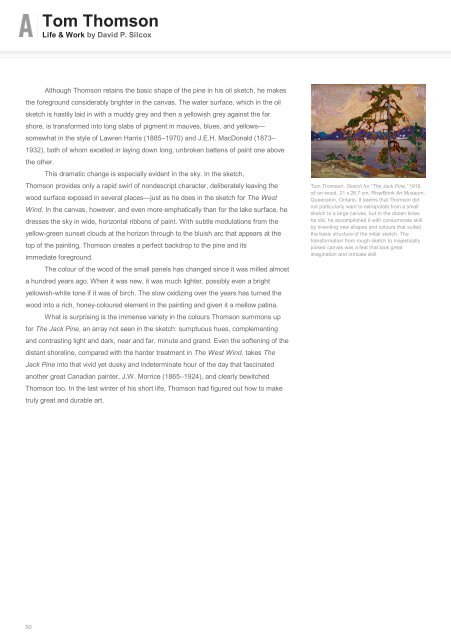

<strong>Tom</strong> <strong>Thomson</strong>, Sketch for “The Jack Pine,” 1916,<br />

oil on wood, 21 x 26.7 cm, RiverBrink Art Museum,<br />

Queenston, Ontario. It seems that <strong>Thomson</strong> did<br />

not particularly want to extrapolate from a small<br />

sketch to a large canvas, but in the dozen times<br />

he did, he accomplished it with consummate skill<br />

by inventing new shapes and colours that suited<br />

the basic structure of the initial sketch. The<br />

transformation from rough sketch to majestically<br />

poised canvas was a feat that took great<br />

imagination and intricate skill<br />

50