You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Tom</strong> <strong>Thomson</strong><br />

Life & Work by David P. Silcox<br />

Diverse Influences<br />

In the early 1900s in Toronto, <strong>Thomson</strong> had no opportunities to see first-hand what<br />

was going on in Europe or even in New York—a city he never visited. The art he was<br />

exposed to came in the form of reproductions in The Studio: An Illustrated Magazine of<br />

Fine and Applied Art and other art magazines, or was filtered through the interpretations<br />

of art movements by his colleagues, the future members of the Group of Seven, all of<br />

whom were trained in art and art history.<br />

Consequently, what we find in <strong>Thomson</strong>’s work are smatterings of many earlier<br />

art movements: Impressionism, Expressionism, Art Nouveau, Arts and Crafts motifs,<br />

stray examples of American versions of French Impressionism, and Victorian and<br />

Edwardian English landscape traditions. The Pointers, 1916–17, shows <strong>Thomson</strong> flirting<br />

with Impressionism, for example, while The West Wind, 1916–17—especially the<br />

foreground and the sinuous branches of the tree—draws on Art Nouveau. <strong>Thomson</strong>’s<br />

nod to Expressionism crops up most strongly in 1916 and 1917 as he moves toward<br />

abstraction in such works as After the Storm, 1917 and Cranberry Marsh, 1916.<br />

Any art books or magazines that floated into <strong>Thomson</strong>’s view would have had<br />

mostly black and white images. From the various influences he eagerly absorbed, he<br />

received a wealth of possibilities, none of which, however, reflected the vital modernist<br />

movements (Cubism, the Fauves, Surrealism) that had been roiling through Europe<br />

during the two decades before his death in 1917.<br />

In works such as Approaching Snowstorm, 1915, <strong>Thomson</strong> was drawn to the<br />

English landscape painter John Constable (1776–1837), who had been introduced to<br />

him by Arthur Lismer (1885–1969) and J.E.H. MacDonald (1873–1932). Constable was<br />

the first artist to approach the landscape not just as a painting genre but as an<br />

experience of a natural event—a rainstorm, a brilliant rainbow, an unusual cloud<br />

formation, a misty sunrise. In this respect, he and his contemporary William J.M. Turner<br />

(1775–1851) rewrote the rules for landscape painting. In 1888 a critic described<br />

Constable’s small oil sketches as “faithful and brilliant transcriptions of the thing of the<br />

moment—nature caught in the very act.” He might have been writing of <strong>Thomson</strong>’s<br />

small sketches almost three decades later.<br />

1<br />

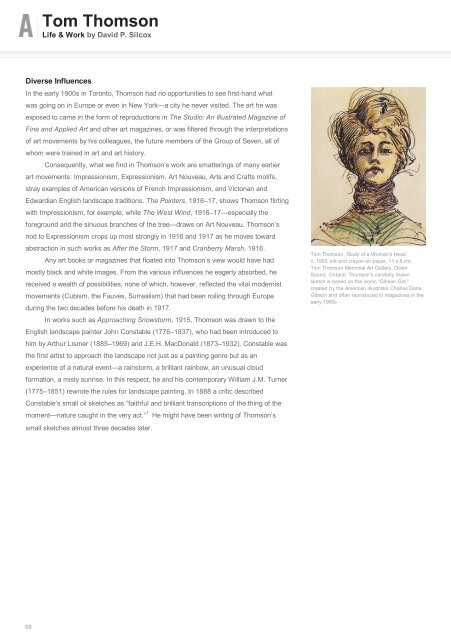

<strong>Tom</strong> <strong>Thomson</strong>, Study of a Woman’s Head,<br />

c. 1903, ink and crayon on paper, 11 x 8 cm,<br />

<strong>Tom</strong> <strong>Thomson</strong> Memorial Art Gallery, Owen<br />

Sound, Ontario. <strong>Thomson</strong>’s carefully drawn<br />

sketch is based on the iconic “Gibson Girl,”<br />

created by the American illustrator Charles Dana<br />

Gibson and often reproduced in magazines in the<br />

early 1900s<br />

68