Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Tom</strong> <strong>Thomson</strong><br />

Life & Work by David P. Silcox<br />

The Canadian Documentary Tradition<br />

The documentary tradition has always been strong in Canada. It arrived with the British<br />

military in the mid-eighteenth century as it recorded Canadian topography in drawings,<br />

watercolours, and oils. Later visitors and settlers such as Paul Kane (1810–1871)<br />

travelled west, eager to paint Aboriginal peoples before, as everyone expected at the<br />

time, they disappeared entirely.<br />

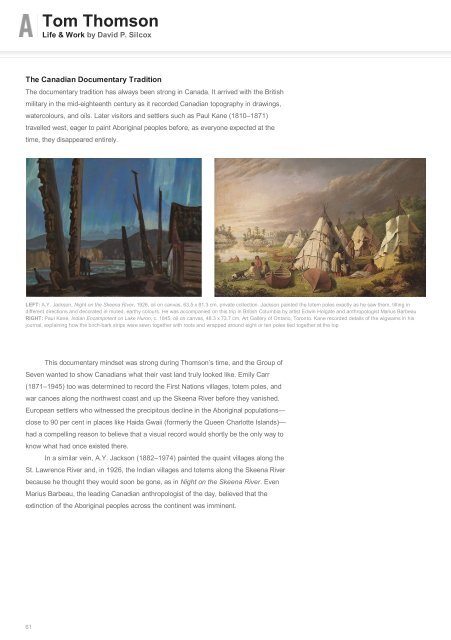

LEFT: A.Y. Jackson, Night on the Skeena River, 1926, oil on canvas, 63.5 x 81.3 cm, private collection. Jackson painted the totem poles exactly as he saw them, tilting in<br />

different directions and decorated in muted, earthy colours. He was accompanied on this trip in British Columbia by artist Edwin Holgate and anthropologist Marius Barbeau<br />

RIGHT: Paul Kane, Indian Encampment on Lake Huron, c. 1845, oil on canvas, 48.3 x 73.7 cm, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. Kane recorded details of the wigwams in his<br />

journal, explaining how the birch-bark strips were sewn together with roots and wrapped around eight or ten poles tied together at the top<br />

This documentary mindset was strong during <strong>Thomson</strong>’s time, and the Group of<br />

Seven wanted to show Canadians what their vast land truly looked like. Emily Carr<br />

(1871–1945) too was determined to record the First Nations villages, totem poles, and<br />

war canoes along the northwest coast and up the Skeena River before they vanished.<br />

European settlers who witnessed the precipitous decline in the Aboriginal populations—<br />

close to 90 per cent in places like Haida Gwaii (formerly the Queen Charlotte Islands)—<br />

had a compelling reason to believe that a visual record would shortly be the only way to<br />

know what had once existed there.<br />

In a similar vein, A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974) painted the quaint villages along the<br />

St. Lawrence River and, in 1926, the Indian villages and totems along the Skeena River<br />

because he thought they would soon be gone, as in Night on the Skeena River. Even<br />

Marius Barbeau, the leading Canadian anthropologist of the day, believed that the<br />

extinction of the Aboriginal peoples across the continent was imminent.<br />

61