You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Tom</strong> <strong>Thomson</strong><br />

Life & Work by David P. Silcox<br />

<strong>Thomson</strong> didn’t abandon his urge to<br />

document as he developed what his patron<br />

Dr. James MacCallum called his “Encyclopedia<br />

of the North.” In Hot Summer Moonlight, 1915,<br />

he captured a common lake scene in Algonquin<br />

Park, though as a nocturne, not, as most artists<br />

preferred, by day. The sermon the future<br />

members of the Group of Seven wanted to<br />

preach to their fellow Canadians relied on<br />

representation. As David Milne (1881–1953),<br />

writing to Harry McCurry of the National Gallery<br />

of Canada, Ottawa, in April 1932, expressed it,<br />

“<strong>Tom</strong> <strong>Thomson</strong> isn’t popular for what aesthetic<br />

qualities he showed, but because his work is<br />

close enough to representation to get by with the<br />

average man.”<br />

6<br />

Judging by his sketches from the spring<br />

and summer of 1917, <strong>Thomson</strong> may have begun<br />

to realize there was a limit to the challenges and<br />

the rewards of Algonquin Park as a subject. If he<br />

was to respond honestly to his deepening sense<br />

of art’s power and of being an artist in touch with<br />

his times, he must have had intimations that he could not go on in that manner forever:<br />

he would have to acknowledge the Expressionist tendency toward abstraction and<br />

gestural painting that was already evident in his work, as revealed in one of his last<br />

sketches, After the Storm, 1917.<br />

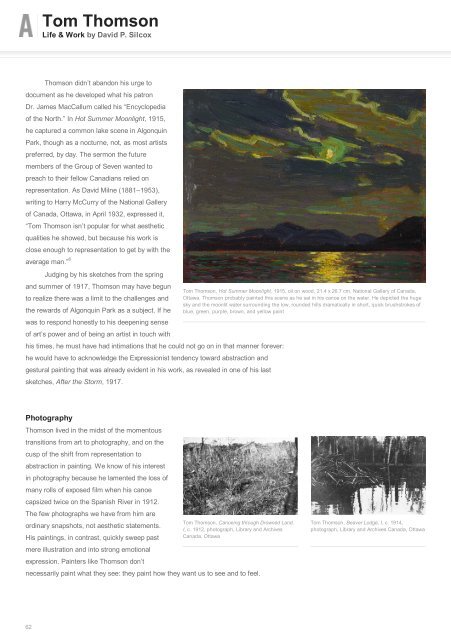

<strong>Tom</strong> <strong>Thomson</strong>, Hot Summer Moonlight, 1915, oil on wood, 21.4 x 26.7 cm, National Gallery of Canada,<br />

Ottawa. <strong>Thomson</strong> probably painted this scene as he sat in his canoe on the water. He depicted the huge<br />

sky and the moonlit water surrounding the low, rounded hills dramatically in short, quick brushstrokes of<br />

blue, green, purple, brown, and yellow paint<br />

Photography<br />

<strong>Thomson</strong> lived in the midst of the momentous<br />

transitions from art to photography, and on the<br />

cusp of the shift from representation to<br />

abstraction in painting. We know of his interest<br />

in photography because he lamented the loss of<br />

many rolls of exposed film when his canoe<br />

capsized twice on the Spanish River in 1912.<br />

The few photographs we have from him are<br />

ordinary snapshots, not aesthetic statements.<br />

His paintings, in contrast, quickly sweep past<br />

mere illustration and into strong emotional<br />

expression. Painters like <strong>Thomson</strong> don’t<br />

<strong>Tom</strong> <strong>Thomson</strong>, Canoeing through Drowned Land,<br />

I, c. 1912, photograph, Library and Archives<br />

Canada, Ottawa<br />

necessarily paint what they see: they paint how they want us to see and to feel.<br />

<strong>Tom</strong> <strong>Thomson</strong>, Beaver Lodge, I, c. 1914,<br />

photograph, Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa<br />

62