EL SALVADOR

8clowSgZh

8clowSgZh

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>EL</strong> <strong>SALVADOR</strong><br />

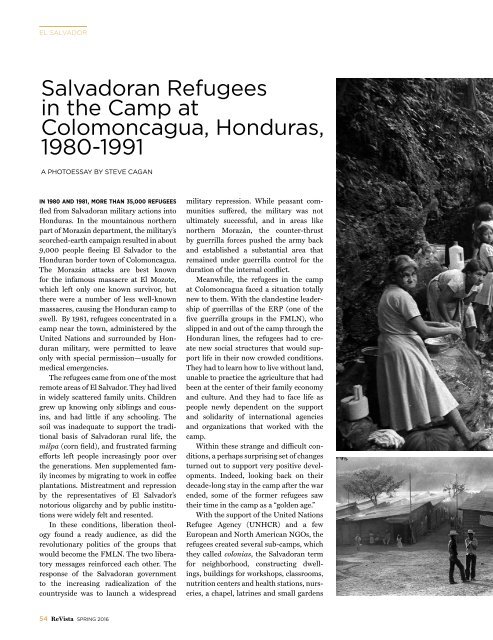

Salvadoran Refugees<br />

in the Camp at<br />

Colomoncagua, Honduras,<br />

1980-1991<br />

A PHOTOESSAY BY STEVE CAGAN<br />

IN 1980 AND 1981, MORE THAN 35,000 REFUGEES<br />

fled from Salvadoran military actions into<br />

Honduras. In the mountainous northern<br />

part of Morazán department, the military’s<br />

scorched-earth campaign resulted in about<br />

9,000 people fleeing El Salvador to the<br />

Honduran border town of Colomoncagua.<br />

The Morazán attacks are best known<br />

for the infamous massacre at El Mozote,<br />

which left only one known survivor, but<br />

there were a number of less well-known<br />

massacres, causing the Honduran camp to<br />

swell. By 1981, refugees concentrated in a<br />

camp near the town, administered by the<br />

United Nations and surrounded by Honduran<br />

military, were permitted to leave<br />

only with special permission—usually for<br />

medical emergencies.<br />

The refugees came from one of the most<br />

remote areas of El Salvador. They had lived<br />

in widely scattered family units. Children<br />

grew up knowing only siblings and cousins,<br />

and had little if any schooling. The<br />

soil was inadequate to support the traditional<br />

basis of Salvadoran rural life, the<br />

milpa (corn field), and frustrated farming<br />

efforts left people increasingly poor over<br />

the generations. Men supplemented family<br />

incomes by migrating to work in coffee<br />

plantations. Mistreatment and repression<br />

by the representatives of El Salvador’s<br />

notorious oligarchy and by public institutions<br />

were widely felt and resented.<br />

In these conditions, liberation theology<br />

found a ready audience, as did the<br />

revolutionary politics of the groups that<br />

would become the FMLN. The two liberatory<br />

messages reinforced each other. The<br />

response of the Salvadoran government<br />

to the increasing radicalization of the<br />

countryside was to launch a widespread<br />

military repression. While peasant communities<br />

suffered, the military was not<br />

ultimately successful, and in areas like<br />

northern Morazán, the counter-thrust<br />

by guerrilla forces pushed the army back<br />

and established a substantial area that<br />

remained under guerrilla control for the<br />

duration of the internal conflict.<br />

Meanwhile, the refugees in the camp<br />

at Colomoncagua faced a situation totally<br />

new to them. With the clandestine leadership<br />

of guerrillas of the ERP (one of the<br />

five guerrilla groups in the FMLN), who<br />

slipped in and out of the camp through the<br />

Honduran lines, the refugees had to create<br />

new social structures that would support<br />

life in their now crowded conditions.<br />

They had to learn how to live without land,<br />

unable to practice the agriculture that had<br />

been at the center of their family economy<br />

and culture. And they had to face life as<br />

people newly dependent on the support<br />

and solidarity of international agencies<br />

and organizations that worked with the<br />

camp.<br />

Within these strange and difficult conditions,<br />

a perhaps surprising set of changes<br />

turned out to support very positive developments.<br />

Indeed, looking back on their<br />

decade-long stay in the camp after the war<br />

ended, some of the former refugees saw<br />

their time in the camp as a “golden age.”<br />

With the support of the United Nations<br />

Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and a few<br />

European and North American NGOs, the<br />

refugees created several sub-camps, which<br />

they called colonias, the Salvadoran term<br />

for neighborhood, constructing dwellings,<br />

buildings for workshops, classrooms,<br />

nutrition centers and health stations, nurseries,<br />

a chapel, latrines and small gardens<br />

54 ReVista SPRING 2016