EL SALVADOR

8clowSgZh

8clowSgZh

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>EL</strong> <strong>SALVADOR</strong><br />

The Migrant<br />

Architecture<br />

of El Salvador<br />

BY SARAH LYNN LOPEZ WITH<br />

PHOTOGRAPHY BY WALTERIO IRAHETA<br />

IN THE SUMMER OF 2015 I TRAV<strong>EL</strong>ED TO THE CITY<br />

of San Salvador to meet photographer Walterio<br />

Iraheta. After publishing my book on<br />

the remittance-funded landscape and architecture<br />

of Mexico, I wanted to learn about<br />

the changing rural landscape caused by El<br />

Salvador’s remittance boom, a subject Iraheta<br />

began photographing in his native<br />

country in 2006. Propelled north since the<br />

1980s and 90s because of the civil war, today<br />

approximately two million Salvadorans—<br />

more than 25% of the country’s total population—live<br />

abroad. The exodus continues,<br />

now fueled by violence and lack of economic<br />

opportunity.<br />

This migration to the United States<br />

is mirrored by a continuous flow of dollars<br />

south. By 2013, the 4.2 billon dollars<br />

streaming into El Salvador’s economy<br />

accounted for an astounding 16 percent of<br />

its GDP. Some migrants have built impressive<br />

new homes— what I call “remittance<br />

homes’”—with dollars earned in the United<br />

States, resulting in dramatic changes across<br />

rural landscapes.<br />

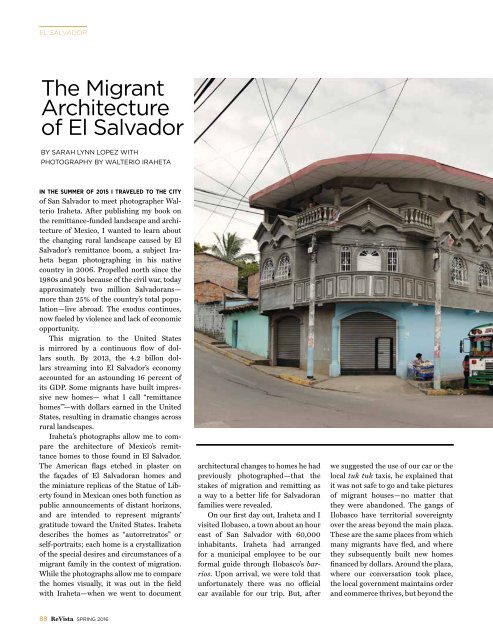

Iraheta’s photographs allow me to compare<br />

the architecture of Mexico’s remittance<br />

homes to those found in El Salvador.<br />

The American flags etched in plaster on<br />

the façades of El Salvadoran homes and<br />

the miniature replicas of the Statue of Liberty<br />

found in Mexican ones both function as<br />

public announcements of distant horizons,<br />

and are intended to represent migrants’<br />

gratitude toward the United States. Iraheta<br />

describes the homes as “autorretratos” or<br />

self-portraits; each home is a crystallization<br />

of the special desires and circumstances of a<br />

migrant family in the context of migration.<br />

While the photographs allow me to compare<br />

the homes visually, it was out in the field<br />

with Iraheta—when we went to document<br />

architectural changes to homes he had<br />

previously photographed—that the<br />

stakes of migration and remitting as<br />

a way to a better life for Salvadoran<br />

families were revealed.<br />

On our first day out, Iraheta and I<br />

visited Ilobasco, a town about an hour<br />

east of San Salvador with 60,000<br />

inhabitants. Iraheta had arranged<br />

for a municipal employee to be our<br />

formal guide through Ilobasco’s barrios.<br />

Upon arrival, we were told that<br />

unfortunately there was no official<br />

car available for our trip. But, after<br />

we suggested the use of our car or the<br />

local tuk tuk taxis, he explained that<br />

it was not safe to go and take pictures<br />

of migrant houses—no matter that<br />

they were abandoned. The gangs of<br />

Ilobasco have territorial sovereignty<br />

over the areas beyond the main plaza.<br />

These are the same places from which<br />

many migrants have fled, and where<br />

they subsequently built new homes<br />

financed by dollars. Around the plaza,<br />

where our conversation took place,<br />

the local government maintains order<br />

and commerce thrives, but beyond the<br />

88 ReVista SPRING 2016