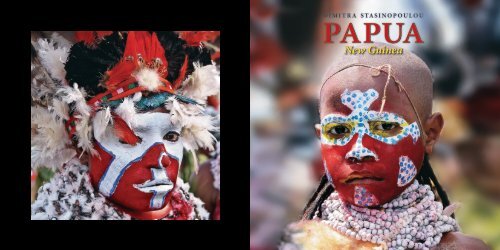

PAPUA

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

DIMITRA STASINOPOULOU<br />

<strong>PAPUA</strong><br />

New Guinea

<strong>PAPUA</strong><br />

New Guinea<br />

PHOTOGRAPHY- TEXT<br />

Dimitra Stasinopoulou

SPONSORED BY:<br />

PRIVATE EDITION<br />

NOT FOR SALE - COMPLIMENTARY COPY

CONTENTS<br />

Dimitra Stasinopoulou was born in Athens, Greece in 1953. After<br />

completing her studies, she worked in the banking sector for 20<br />

years, and later on, in the family business in Romania. Her first<br />

Book “Romania of my Heart” was awarded with the Romanian<br />

UNESCO prize. Ever since then, her love of travelling to amazing<br />

destinations around the globe and her desire to share the images<br />

she brought back with her, led her to the publiction of the books<br />

“Bhutan, Smiling Faces from the Roof of the World” in October<br />

2008 and “India, Unity in Diversity” in March 2010. Her pictures<br />

have been awarded in international photo-competitions and have<br />

been displayed in Greece and abroad.<br />

INTRODUCTION 8 - 15<br />

THE HIGHLANDS<br />

The Tari region and the Huli Tribe 16 - 95<br />

THE RIVER SEPIK 96 - 139<br />

THE HIGHLANDS<br />

Mount Hagen Sing-Sing Annual Festival 140 - 237<br />

PACIFIC OCEAN<br />

Madang and the surrounding islands 238 - 276

7

It has been many years since I wanted to visit Papua New<br />

Guinea, to experience the authenticity of its culture<br />

and the unchanged way of life of its residents. Τhis was not,<br />

however, a journey that one can easily decide upon. The<br />

information available on the country is minimal, the tourism<br />

infrastructure almost non-existent, whilst it is plagued by<br />

malaria, tuberculosis and other diseases. Moreover, tribal<br />

clashes are not rare; these are small-scale but particularly<br />

violent, conflicts usually involving a local character that can<br />

keep the visitor trapped in a dangerous region for many days.<br />

It is not a coincidence that the country has only 40,000 foreign<br />

visitors each year.<br />

Yet, all this is only one side of the coin; on the other is the<br />

discovery of a country that has been left untouched by the<br />

passage of time, covering in just a few decades the dizzying<br />

distance from the Neolithic period to the modern world, the<br />

singular feeling of encountering a society that stubbornly<br />

insists on sticking to its primeval traditions. So, in August<br />

2009 –the best month to visit the country in order to experience<br />

the wonderful Mt Hagen Sing-Sing, the country’s largest festival<br />

– I was there.<br />

It is truly very difficult for me to describe the surprise I felt<br />

when i found myself, for the first time, in the sanctum of an<br />

aboriginal village and an ancient civilisation, unchanged for<br />

millennia. You have the feeling of having just travelled in time:<br />

from the high-tech era of globalisation and communications, to<br />

the age of tools, hunting and magic, at the dawn of human life.<br />

However much one might try, it is impossible to “fit” such<br />

a distinctive country into economic figures, political practices<br />

and demographic equations. Tradition surfaces everywhere and<br />

composes a perfectly harmonised universe of primitive farming,<br />

ancient customs and an economic outlook that is foreign to us<br />

and limited to necessities. Even the meaning of democracy, a<br />

“The world only exits when it is shared”<br />

Tasos Livaditis, Greek poet<br />

foundation stone of modern states based on the rule of law, can<br />

be understood only with difficulty by the different tribes of the<br />

hinterland, which have been based for centuries now on the<br />

power of the tribal shaman and the counsel of the elders who,<br />

in a land where few reach an old age, are clearly considered<br />

holders of invaluable experience and wisdom.<br />

Until 1930, the hinterland had not been explored at all; the<br />

Europeans considered these wild and mountainous regions as<br />

inhospitable for living in. Only in the mid-20th century did a<br />

couple of Australian gold diggers, who were searching for gold<br />

deposits at higher altitudes, discovered, amazed, that around<br />

a million people lived in these wild areas, isolated from the<br />

fertile mountain valleys and preserving a civilisation almost<br />

unchanged since Neolithic times. This was an astonishing<br />

discovery for the Western world as at that time everyone<br />

believed that the planet had been fully explored and mapped<br />

in detail: given the sight of such a primitive society, scientists –<br />

botanists, anthropologists and archaeologists – politicians and<br />

journalists, proved unable to rise to the occasion and, without<br />

prior research, debate and reflection, suddenly invaded this<br />

foreign world, bearing the miracles of technology and their<br />

Western culture to people completely unprepared for such a<br />

change. Thankfully, however, even in our days, the exceptional<br />

difficulty in accessing their hinterland and the refusal of<br />

the inhabitants to lose their cultural identity has meant that<br />

European influence has been relatively limited.<br />

Today the Independent State of Papua New Guinea, as it is<br />

officially known, is a state that is working hard to modernise<br />

and to battle diseases, illiteracy and barbaric customs wherever<br />

they still exist. It is transitioning from a barter economy to a<br />

money economy, and hopes in the future to see its great natural<br />

and mineral wealth being put to use. It is not easy however to<br />

subdue a people that has learnt to live free, organised in small<br />

independent social groupings comprised of a few villages; a<br />

people that has learnt to apply a system of justice devised not<br />

by legislators but by centuries and myths. It is thus difficult<br />

to uproot the practice of centuries, of superstitions and selfgoverned<br />

and autonomous local societies from the life of the<br />

Papua overnight.<br />

My journey to New Guinea gave me unique experiences but<br />

above all it gave me the gift of a colourful society that is very<br />

old and that follows the thread of its own distinctive history.<br />

And yet I found myself unprepared – truth be told, no one can<br />

prepare themselves for what they will see in front of them –<br />

within these colours, dances, isolated tribes, strange languages;<br />

I felt a foreigner – burdened with the baggage of a completely<br />

different culture – and the great need to find an object that<br />

was mine, something familiar and loved to have as my ally.<br />

So I kept my camera; an achievement of digital technology<br />

a worthy representative of my familiar world, searching with<br />

its lens to find not only what separates us from these people<br />

but also what unites us. No matter how many journeys one<br />

might take, whichever part of the planet they may find<br />

themselves, every time they will see the cheeky smile of a<br />

child, the impetuous gaze of the adults and the stoic, welcome<br />

expression of the elders demonstrating that, under the<br />

successive layers of culture, we all have the same face, the same<br />

voice, the same body.<br />

After many days in this strange and wonderful land I<br />

considered that I had by now formed a fairly complete picture<br />

of it: I’d explored the Highlands, their wonderful mountains<br />

and local tribes, I’d seen their greatest festival, the unique<br />

Mount Hagen Sing-sing, I’d toured the banks of the Sepik, the<br />

largest river, had faced the ocean at Madang beach and had<br />

visited some of the islands. After all this wandering I once more<br />

felt my values being shaken. No one doubts that it is imperative<br />

that steps are taken – and immediately – for modernisation and<br />

to fight the spread of diseases, illiteracy and the often barbaric<br />

customs and inhumane rituals. What, however, is the correct<br />

way to make such a violent intervention into the history of a<br />

place more moderate, to smooth its transition to a new reality?<br />

Do others, in this case us, the developed nations; decide on<br />

the fate of people unable to respond in the face of the cultural<br />

steamroller of technology? Are we to take the risk that, along<br />

with all that is wrong in these primitive societies, their valuable<br />

individuality will also be lost, their completely idiosyncratic<br />

view of life, the hundreds of languages, their unique art?<br />

How can we be sure that the society of the Papua will adjust<br />

smoothly to a world that, to its eyes, seems to be coming from<br />

the far future?<br />

Yes, I was certainly delighted with the wonderful journey<br />

that was coming to a close, for having had the good fortune to<br />

touch for myself something so primitive and authentic. Even so,<br />

I could not avoid a feeling of imperceptible sorrow, a nostalgia<br />

for something that will be lost: a mud village, a beseeching<br />

popular belief, a unique language; a pure piece of human<br />

history, true and undefended.<br />

THE INHABITANTS AND THEIR DAILY LIVES<br />

Whichever part of the country I went to I encountered<br />

people who were calm and true; people who moved about with<br />

humility and an inherent dignity that was in complete harmony<br />

with their natural environment and who were reconciled to<br />

the innate difficulties it entailed. You believe that in their every<br />

movement, in their colorful costumes and the strange steps<br />

of their dances, you are witnessing an unending attempt to<br />

appease the bad spirits, the wrath of nature and their vengeful<br />

gods (despite the establishment of Christianity, the primeval<br />

beliefs still maintain a prominent position in religious life).<br />

A main feature, however, of their social and cultural life is the<br />

globally unique heterogeneity of the population. The indigenous<br />

population is divided into thousands of different communities,<br />

most of which only number a few hundred members. With their<br />

own customs and their own languages and traditions, many<br />

of these groups have been in conflict with their neighboring<br />

tribes for millennia. In some cases, because of the mountainous<br />

landscape and the isolation it imposes, many were completely<br />

unaware of neighboring tribes who lived only a few kilometers<br />

away. This heterogeneity, the differences in the bosom of one<br />

people, which can perhaps best be summed up in one of the<br />

8 9

island’s folk sayings according to which “for each village, a<br />

different culture”, is apparent in the number of languages and<br />

local dialects, of which there are over 800. Of these, less than<br />

half are related to each other whilst the others appear to be<br />

completely independent, unrelated to any of the island’s other<br />

languages or any larger language groups.<br />

The inhabitants have more in common in terms of their diet,<br />

as amongst the main foods we always find starchy vegetables,<br />

bananas, mangoes, coconuts and other fruits. Their meat supply<br />

comes mainly through rearing pigs and poultry as well as<br />

hunting, whilst in the coastal areas fish and seafood are a main<br />

element of the local diet.<br />

Prior to the coming of the Europeans, there were no<br />

towns anywhere in the country. During the colonial period<br />

the scattered settlements were merged into larger villages<br />

for the first time, making them easier to govern and provide<br />

education and health services. The first towns grew around the<br />

administrative centers and the missionaries and at first housed<br />

only men, who worked mainly in construction. These towns<br />

gradually grew into the country’s urban, political, administrative<br />

and commercial centers.<br />

As regards social stratification, there are no castes and social<br />

classes only developed recently: in general, one could say that<br />

the society is divided into the “upper class” and the “simple<br />

citizens”. The first group includes the educated, high-income<br />

town dwellers (the “coffee millionaires,” in the local lingo), and<br />

the second group includes the inhabitants of the countryside<br />

and the low-income town dwellers. In the past few years a<br />

middle class has begun to emerge. Even so, the villagers are<br />

not poor, or at least not in the sense that we mean poor. You<br />

would be hard pushed to find in the microeconomic activities<br />

of the tribes any kind of accumulation of goods and wealth, and<br />

consumption as a way of life is completely incomprehensible.<br />

The annual income per capita of these people may not be more<br />

than a few dollars but in a barter economy such as there still<br />

is to a great extent, no one lacks essential goods. Whatever<br />

money is available is invested in the development of social and<br />

political relations within the tribe or village, through which the<br />

members of each local society maintain their position in the<br />

tribal hierarchy.<br />

Labor within the village is divided less on the basis of position<br />

and more on the basis of gender; the men build the houses and<br />

the dams, they hunt, they fish and they cultivate the banana,<br />

coffee and cocoa. The women grow all the other vegetables, rear<br />

the poultry and pigs, weave baskets and clothes and raise the<br />

children. Any income from the sale of coffee and cocoa is taken<br />

by the men, who are socially stigmatized in both the villages<br />

and the towns, if they commit the “crime” of performing work<br />

that is traditionally attributed to women. Things have changed<br />

somewhat today and a hard-working woman is given her due<br />

respect - she may even leave her husband for someone else<br />

without suffering any social stigma if her husband is deemed<br />

not to have cared for her as he should have.<br />

Marriage takes place as an agreement between two families<br />

and very rarely as the personal choice of the couple. A girl’s<br />

parents will hope to marry her to a wealthy man, whilst what<br />

is sought for in a woman, is first that she is willing to work<br />

and secondly her external appearance. Polygamy is generally<br />

accepted for men as traditionally a well-built man always<br />

enjoyed a greater share of the women.<br />

There is an unheard of tolerance in the rearing of children<br />

throughout almost the whole island, at least for the first five or<br />

six years of their lives. This is due to the common conviction<br />

that the spirit of a small child may abandon its body if it is<br />

hit or frightened. The selfishness, cruelty or malevolence of<br />

some children are ascribed to bad spirits and not to the child<br />

themselves or their bad upbringing. In these cases the parents<br />

often invite a priest-magician to expel the evil and restore calm<br />

to their home. As they grow towards adulthood children are<br />

taught by following the examples of adults, participating in<br />

various, often inhuman, initiation rituals. All this preparation is<br />

considered essential in order for the young adult to be able to<br />

respond fully to their social and marital responsibilities.<br />

Almost patriarchal societies keep women at a distance and<br />

in clearly distinct roles. As described above, the process of<br />

separating small boys from their mothers begins at an early age:<br />

they start to sleep far from women, in the houses of men, whilst<br />

in many tribes there are initiation rituals into the world of<br />

men, so as to remove all traces of female influence and achieve<br />

full catharsis of the pollution from the “hot” discharges of the<br />

female body.<br />

As for religion, approximately 96% of the population is<br />

Christian. Of course, as often happens in many cases where<br />

Christianity coexists alongside preceding religions, what<br />

eventually arises is a completely new fusion, with Christian<br />

practices being combined with primeval beliefs – prayers to<br />

Christ in order to expel the subterranean spirits, monsters and<br />

the invisible creatures of the forest. The traditional religions<br />

are often animistic and include elements of ancient worship.<br />

A prevailing belief amongst the traditional tribes is that of the<br />

masalai, the bad spirits who have the power to provoke death<br />

and destruction. Another common conviction is the parallel<br />

existence of the physical and metaphysical world; in order for<br />

the living to prosper, the interaction between the two worlds<br />

necessitates the observation of customs and the preservation of<br />

social ties, such as satisfying the spirits of the dead ancestors,<br />

who continue to observe, beyond the bounds of death, the<br />

activities of the tribe. Very few accidents, illnesses or deaths are<br />

attributed to chances or natural causes. Almost every fatal event<br />

is attributed to curses, angry water or forest spirits or simply to<br />

the vengeance of the insulted ghost of an ancestor. Great store is<br />

put upon the use of a magical substance known as “mana”, and a<br />

large number of natives have knowledge of magic.<br />

Much has been said about the cannibalism of the Papua; it<br />

has even been claimed that the first Australian explorers who got<br />

as far as the isolated regions of the hinterland in around 1930,<br />

provided a most nutritious meal for their hosts. Nonetheless,<br />

the truth is that cannibalism had a prominent place in the<br />

cult practice and burial customs of many of the island’s tribes,<br />

who believed that by eating the dead they would acquire their<br />

positive characteristics, gaining strength and bravery. Women<br />

often ate a part of their dead husband so as to absorb something<br />

of his masculinity into their female nature.<br />

The kuru disease (or “laughing sickness”, as the symptoms<br />

include pathological outbursts of laughter) has been<br />

demonstrated to result from the ritual practice of cannibalism,<br />

in particular of the Fore tribe in the Eastern Highlands. This<br />

is an incurable and fatal neurological disorder, a transmissible<br />

spongiform encephalopathy that appeared for the first time in<br />

the mid-20th century and spread progressively in the form of<br />

an epidemic to the neighbouring regions. It primarily affects<br />

women and children, due to deposits of the protein particle<br />

prion in the human brain, which showed a preference for the<br />

“weaker” members of the tribe: during Fore burial customs<br />

those present had to honour the dead by eating them. Men<br />

chose first which pieces they would eat and the rest of the body<br />

went to the women and the children, including the infected<br />

brain. The kuru disease was studied by the American physicians<br />

Daniel Carleton Gajdusek and Baruch S. Blumberg, who proved<br />

the infectious nature of this type of encephalopathy for the<br />

first time, for which they won the Nobel Prize for Medicine in<br />

1976. The disease gradually disappeared when cannibalism was<br />

abolished through the implementation of Australian colonial<br />

laws and the efforts of the local missionaries.<br />

The majority of the inhabitants, approximately 84%, belong<br />

to groups of the Papua tribe. The oldest is the Negrito tribe<br />

(Pygmies), whilst amongst the autonomous Papua tribes are,<br />

the Orokolo, known also as the “People of the Sea”, the Daudai,<br />

the Goigala and others. Also of great interest are the huge<br />

demographic diversity and the over 820 languages spoken on<br />

the island, comprising one-fifth of the world’s total languages.<br />

The official language is English, which is used in education and<br />

by the authorities, whilst the main languages of daily speech<br />

are the Creole Tok Pisin and, in the south, Hiri Motu. Tok Pisin<br />

(Tok = talk, Pisin = pidgin) developed as a necessary means of<br />

communication between the Melanesian colonists who worked<br />

on the plantations of Queensland in northwest Australia. These<br />

workers, who spoke countless different languages, gradually<br />

started to develop a language structure, drawing the vocabulary<br />

10 11

mainly from English as well as German, Portuguese, Melanesian<br />

and their own local languages. Tok Pisin, which later spread to<br />

New Guinea, provided an important channel of communication<br />

between the various tribes of the island, who up until then had<br />

been entrenched within the narrow linguistic boundaries of<br />

their tribal group. This often created problems and conflicts as<br />

it made it difficult for differences to be resolved. The country’s<br />

schools play a role that is much more than educational, that of<br />

enabling communication, as the common use of English brings<br />

neighbouring and also distant tribes into contact with each<br />

other.<br />

The economy is agrarian and the majority of the inhabitants<br />

farm with, literally, primitive means. The Highlanders were<br />

amongst the first farmers in history and the social structure<br />

of their settlements is based on a particular form of equality,<br />

most likely even older than most Western democracies. Much<br />

has remained unchanged in their lives: cultivation of the sweet<br />

potato has been the basis of their economy for the past 300<br />

years. Prior to this they had grown primarily taro but the sweet<br />

potato, which had been imported from Indonesia, could grow<br />

on almost all grounds and provide two to four harvests a year.<br />

Its cultivation thus led to greater productivity and, consequently,<br />

to greater wealth: with the production surplus the Highlanders<br />

bought pigs, which they then used to marry a hard-working<br />

wife who would help them grow even more sweet potatoes.<br />

The entire economic activity thus acquired another dynamic as<br />

commercial exchange now became a part of daily life: pigs and<br />

sweet potatoes were often exchanged for salt, blades, animal<br />

skins, etc. Furthermore, jewellery, weapons and ritual objects<br />

were often exchanged, thus bringing closer together tribes that<br />

were enemies but yet still shared common ritual practices, and<br />

maintaining – on rare occasions – a fragile peace to the region.<br />

THE COUNTRY<br />

The island state of Papua New Guinea is located to the north<br />

of Australia and includes the east section of the island of New<br />

Guinea, with the west section, the region of Irian Jaya, belonging<br />

to Indonesia. Papua New Guinea includes numerous islands<br />

and coral islands in the Pacific Ocean, as well as the island<br />

groups of New Ireland, New Britain, the Admiralty Islands, the<br />

Solomon Islands and the Bismarck Archipelago. Many of these<br />

are volcanic.<br />

The country covers an area of 462,840 square kilometres and,<br />

along with the east section, is the world’s second largest island<br />

after Greenland and perhaps also the highest, with mountain<br />

ranges over 5,000 metres in altitude. The island was created<br />

by the crashing together of the tectonic plates of Eurasia and<br />

Australia. Approximately 80% of the hinterland is covered by<br />

tropical forests, with equatorial vegetation. In the country’s<br />

almost virgin natural environment countless species of flora<br />

and fauna find a refuge, both Asian and Australian in origin as<br />

well as endemic species, the catalogue of which is constantly<br />

growing as there are many regions that are still being explored<br />

or remain completely unexplored. The island also has the<br />

world’s richest bird fauna, with over 700 species and almost all<br />

the known species of birds of paradise (of the 42 species in the<br />

world, the island has 38), as well as the largest variety of orchids<br />

in the world.<br />

Both the climate and the particular geology of New Guinea as<br />

well as the minimal human intervention into the environment –<br />

the industrial revolution never arrived here – have contributed<br />

to the development of one of the world’s most important<br />

ecosystems, with a huge biodiversity: almost 19% of the world’s<br />

species of flora and fauna find refuge on the island. As might<br />

be expected, the country remains unexplored to a great extent,<br />

both from a natural and a cultural perspective. It is considered<br />

a paradise for botanists, zoologists and anthropologists. Every<br />

so often a new species of plant or animal is discovered in the<br />

depths of the New Guinea jungle, or a new social structure<br />

thousands of years old is located in some unexplored mountain<br />

settlement, transporting researchers into the past, literally into<br />

the object of their study.<br />

We could say that the New Guinea hinterland is divided by<br />

steep mountain ranges which cannot be reached by road, aside<br />

from a few ad hoc footpaths created during the Second World<br />

War. Only by flying, sailing or hiking can one approach these<br />

parts. Despite the isolation, the broader area of the Highlands,<br />

as they are known, and the central mountain valleys in<br />

particular are the most fertile and densely-populated parts of<br />

the country, aside, of course, from the few urban centres.<br />

The country is crossed by a dense network of rivers, which<br />

flow from the central mountain regions and discharge into<br />

the Pacific coasts. The largest rivers are the Sepik in the north,<br />

which crosses the country flowing in the direction of the<br />

Bismarck Sea, the Fly in the south, which discharges in the Gulf<br />

of Papua, and the Ramu. These rivers are for their greater parts<br />

navigable, offering an important alternative route for accessing<br />

the most central regions of the hinterland.<br />

The climate is tropical, humid and warm, with an average<br />

temperature of 28 degrees Celsius. At the higher altitudes the<br />

climate is almost equatorial mountain, whilst rainfall is heavy<br />

and frequent everywhere.<br />

The country has a population of approximately 6,000,000,<br />

with only 17% of the total residing in the urban centres. Port<br />

Moresby, the capital, is the most densely populated town in<br />

Papua New Guinea, with over 270,000 inhabitants, and the<br />

country’s largest port and its international airport. Other large<br />

urban centres are Lae, with approximately 115,000 inhabitants,<br />

and Madang, with 33,000 inhabitants on the northeast coasts.<br />

Demographically, it has a rapidly rising population, relatively<br />

short life expectancy and high birth rate.<br />

There are low levels of production, serving primarily the<br />

subsistence needs of the inhabitants and leaving little margin<br />

for even limited exports. The main crops are coffee, cocoa,<br />

papaya, coconuts, rubber, etc. Even so, despite the country’s<br />

very low GDP and its minimal per capita income (only 1,294<br />

US dollars), Papua New Guinea has an incredibly rich subsoil<br />

with significant deposits of resources, such as gold, natural<br />

gas, cobalt, oil, silver, copper, etc. Of these, gold and silver are<br />

exported to neighbouring countries. The country is a member<br />

of the British Commonwealth and the head of state is Queen<br />

Elizabeth II, her role being purely symbolic. Executive power is<br />

in the hands of the prime minister, whilst legislative power lies<br />

with the National Parliament, which has 109 elected members.<br />

THE HISTORY<br />

The island state of Papua New Guinea is located to the north<br />

of Australia and includes the east section of the island of New<br />

Guinea, with the west section, the region of Irian Jaya, belonging<br />

to Indonesia. Papua New Guinea includes numerous islands<br />

and coral islands in the Pacific Ocean, as well as the island<br />

groups of New Ireland, New Britain, the Admiralty Islands, the<br />

Solomon Islands and the Bismarck Archipelago. Many of these<br />

are volcanic.<br />

The country covers an area of 462,840 square kilometres and,<br />

along with the east section, is the world’s second largest island<br />

after Greenland and perhaps also the highest, with mountain<br />

ranges over 5,000 metres in altitude. The island was created<br />

by the crashing together of the tectonic plates of Eurasia and<br />

Australia. Approximately 80% of the hinterland is covered by<br />

tropical forests, with equatorial vegetation. In the country’s<br />

almost virgin natural environment countless species of flora<br />

and fauna find a refuge, both Asian and Australian in origin as<br />

well as endemic species, the catalogue of which is constantly<br />

growing as there are many regions that are still being explored<br />

or remain completely unexplored. The island also has the<br />

world’s richest bird fauna, with over 700 species and almost all<br />

the known species of birds of paradise (of the 42 species in the<br />

world, the island has 38), as well as the largest variety of orchids<br />

in the world.<br />

The climate and the particular geology of New Guinea as<br />

well as the minimal human intervention into the environment<br />

have contributed to the development of one of the world’s most<br />

important ecosystems, with a huge biodiversity: almost 19%<br />

of the world’s species of flora and fauna find refuge on the<br />

island. As might be expected, the country remains unexplored<br />

to a great extent, both from a natural and a cultural perspective.<br />

It is considered a paradise for botanists, zoologists and<br />

12 13

anthropologists. Every so, often a new species of plant or animal<br />

is discovered in the depths of the New Guinea jungle, or a<br />

new social structure thousands of years old is located in some<br />

unexplored mountain settlement, transporting researchers into<br />

the past, literally into the object of their study.<br />

We could say that the New Guinea hinterland is divided by<br />

steep mountain ranges which cannot be reached by road, aside<br />

from a few ad hoc footpaths created during the Second World<br />

War. Only by flying, sailing or hiking can one approach these<br />

parts. Despite the isolation, the broader area of the Highlands,<br />

as they are known, and the central mountain valleys in<br />

particular are the most fertile and densely-populated parts of<br />

the country, aside, of course, from the few urban centres.<br />

The country is crossed by a dense network of rivers, which<br />

flow from the central mountain regions and discharge into<br />

the Pacific coasts. The largest rivers are the Sepik in the north,<br />

which crosses the country flowing in the direction of the<br />

Bismarck Sea, the Fly in the south, which discharges in the Gulf<br />

of Papua, and the Ramu. These rivers are for their greater parts<br />

navigable, offering an important alternative route for accessing<br />

the most central regions of the hinterland.<br />

The climate is tropical, humid and warm, with an average<br />

temperature of 28 degrees Celsius. At the higher altitudes the<br />

climate is almost Equatorial Mountain, whilst rainfalls are heavy<br />

and frequent everywhere.<br />

The country has a population of approximately 6,000,000,<br />

with only 17% of the total residing in the urban centres. Port<br />

Moresby, the capital, is the most densely populated town, with<br />

over 270,000 inhabitants, and the country’s largest port and its<br />

international airport. Other large urban centres are Lae, with<br />

approximately 115,000 inhabitants, and Madang, with 33,000<br />

inhabitants on the northeast coasts. Demographically, it has a<br />

rapidly rising population, relatively short life expectancy and<br />

high birth rate.<br />

There are low levels of production, serving primarily the<br />

subsistence needs of the inhabitants and leaving little margin<br />

for even limited exports. The main crops are coffee, cocoa,<br />

papaya, coconuts, rubber, etc. Even so, despite the country’s<br />

very low GDP and its minimal per capita income (only 1,294<br />

US dollars), Papua New Guinea has an incredibly rich subsoil<br />

with significant deposits of resources, such as gold, natural<br />

gas, cobalt, oil, silver, copper, etc. Of these, gold and silver are<br />

exported to neighbouring countries.<br />

The country is a member of the British Commonwealth and<br />

the head of state is Queen Elizabeth II, her role being purely<br />

symbolic. Executive power is in the hands of the prime minister,<br />

whilst legislative power lies with the National Parliament, which<br />

has 109 elected members.<br />

Dimitra Stasinopoulou<br />

Athens, September 2011<br />

BIBLIOGRAPHY<br />

Asia Transpacific Journeys, information leaflet, 2009<br />

Beck, Howard. Papua New Guinea, Tales from a Wild Island, London: Robert<br />

Hale, 2009<br />

Busse, Mark, Susan Turner and Nick Araho, The People of Lake Kutubu and<br />

Kikori, Changing Meanings of Daily Life, New Guinea: National Museum of<br />

Papua New Guinea, 1993<br />

Corazza, Iago and Greta Ropa, The Last Men, Journey among the tribes of New<br />

Guinea, Vercelli: Whitestar Publishers, 2008<br />

Diamond, Jared. Guns, Germs and Steel, New York: Norton Press, 1997<br />

Gascoigne, Ingrid. Papua New Guinea, Cultures of the World, New York:<br />

Marshall Cavendish Benchmark, 2010<br />

Gewertz, Deborah. Sepik River Societies, New Haven: Yale University<br />

Press, 1983<br />

Levi-Strauss, Claude. Myth and Meaning, U.K., Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978<br />

McKinnon, Rowan, Jean-Bernard Carillet and Dean Starnes, Papua New Guinea<br />

& Solomon Islands, Lonely Planet, 2008<br />

Noakes, Suzanne (ed.), Island in the Clouds, collection of articles<br />

on New Guinea<br />

Sullivan, Nancy. A Brief Introduction to the History, Culture and Ecology of<br />

Papua New Guinea, information leaflet by Trans Niugini Tours<br />

14 15

THE HIGHLANDS<br />

The Tari region and the Huli tribe<br />

The best-known of the Highland tribes is the Huli, in the region of Tari, which is surrounded<br />

by verdant valleys squeezed into limestone peaks with scattered rushing waterfalls and dense<br />

forests, where one can meet most of the species of the birds of paradise. The Huli tribe<br />

numbers approximately 80,000 members. They are usually short and muscular with a strong<br />

and proud personality, and they often act altruistically for the common good, despite their<br />

individualism. They have a clear awareness of both their history and culture, as can be seen<br />

in their knowledge of their genealogical trees and of their traditions. They believe that they<br />

descend from an ancient ancestor known as Huli, The Son of the Forest Spirits and the first,<br />

according to tradition, farmer in the region.<br />

The status of leader is not handed down; one becomes socially powerful through their<br />

military qualities, the wealth they have collected and their skills as a mediator in solving<br />

tribal differences. The Huli are certainly not a peaceful tribe. They live constantly at war, with<br />

many small local disputes that are often unrelated, as the causes are almost always personal<br />

disagreements and not some traditional enmity with another tribe. They fight primarily for<br />

three reasons: land, pigs and women, and in that order. Other main characteristics of the Huli<br />

are the unusual relationship between the two sexes and the extensive practice of magic in<br />

religious life. As for the women, because of their great power to create life, they are considered<br />

by the men of the tribe to be a permanent threat to their masculinity. The use of magic is<br />

particularly widespread as the Huli religion is clearly animistic, being founded on the belief<br />

in the existence of spirits that animate every manifestation of the natural world. For the Huli,<br />

everything has a soul: the forest, the mountain, the river, the sun and the animals, and all are<br />

potential spiritual entities that require supplication, worship and appeasement.<br />

Youths are separated from their mothers and gradually from every woman for a period of<br />

isolation that lasts from one-and-a half to three years. During this period they live isolated<br />

from female company, purging themselves of every female “essence” and growing their hair.<br />

At the end of this purging period they cut their long and well-cared hair and make their<br />

famous wigs, for which the Huli have become known as the “Wigmen”. During this period<br />

it is forbidden to sleep with their heads touching the ground and they are obliged to drizzle<br />

magic water over their heads every day, expelling the bad spirits. These wigs are adorned<br />

with the plumes of birds of paradise and signify self-denial and catharsis as characteristics of<br />

masculinity. After this purging the young man is ready to handle the “threat” of coupling and<br />

the responsibilities of marriage.<br />

Nonetheless, the Huli, despite their superstitious beliefs, do not hesitate in resorting to<br />

western medicine when suffering from a serious illness. In the Tari region I had the opportunity<br />

to visit a Doctors without Borders clinic: dozens of helpless and seriously ill people were<br />

patiently waiting their turn to receive medical care in one of the ad hoc clinics that had been<br />

set up, without losing the smile from their faces. Malaria, Aids and tuberculosis can count<br />

many victims here, and the doctors work truly selflessly against these illnesses, in absolutely<br />

primitive conditions.<br />

Drizzling ‘magic’ water Wig maker Tari School Inside a school class The tribe doctor<br />

Working in the fields<br />

Basket weaving, Tari Naive paintings Hunter in Mt Hagen Medecins Sans Frontieres

19

21

23

25

27

29

30

33

34

36

39

41

43

44

47

49

51

53

55

57

58

61

62

65

67

68

71

72

75

76

78

80

83

84

86

88

91

93

94

THE RIVER SEPIK<br />

No one knows with any certainty what the meaning of the word Sepik is, although it is claimed that it<br />

means “Large River”, something that is certainly believable when you first set eyes on this imposing river<br />

with its length of 1,125 kilometres. The country’s most stunning natural landscape unfolds around this<br />

huge mass of water, which flows from the Victor Emmanuel mountain range in the central Highlands.<br />

Tropical forests, cultivable mountain ranges, verdant mountains and marshy wetlands alternate along<br />

the length of the Sepik, home to the island’s greatest variety of flora and fauna as well as some of its most<br />

interesting tribes. The most isolated settlements remain almost untouched by Western influence.<br />

The Sepik is the island’s largest river and one of the largest river systems in the world. Like the Amazon,<br />

it is serpentine in shape, and discharges into the Bismarck Sea without forming a delta. The river is<br />

navigable for the greatest part and serves the travel and transport needs of its people. It is, however, a<br />

hydrological system that is ceaselessly adapting, changing its flow and creating new basins; the tribes that<br />

live along its banks are often forced to relocate so as to follow its new direction.<br />

Over 250 different linguistic groups live in this region. Each settlement also comprises an autonomous<br />

“ethnic” group, even though many of the villages are linked either by tribal or trade relations. It is perhaps<br />

to these extensive transactions between the Sepik tribes – aided by navigation along the river – that we<br />

can ascribe the increased need of the people here to preserve their cultural independence, their particular<br />

history, language, folk art and mythology. All these tribes consider their oral traditions, which have been<br />

handed down from generation to generation for thousands of years, to be of the utmost importance. The<br />

first contact that these tribes had with Europeans was in 1885, during German exploration of this region<br />

when it was a part of German New Guinea.<br />

Although many settlements are self-sufficient, trade is a basic part of economic life. Each tribe has a<br />

unique product that it exchanges for the unique products of the other tribes (I should mention here that<br />

women are also among the “goods” that are exchanged between the villages). The diet is based on saksak,<br />

a type of flour that is produced by the pith of the sago palm tree that flourishes in the region. Although<br />

flour is an exclusively starchy food, for the inhabitants of the area, it provides a dependable nutritional<br />

solution and without requiring any farming. Their diet is occasionally supplemented with fish, game and<br />

some garden vegetables which they grow during the dry season as the heavy rainfall throughout the rest<br />

of the year prohibits almost all other types of crops. This stability in the supply of living necessities is<br />

considered by many to be a main factor in the noteworthy development of arts in the Sepik region. The<br />

famous sculptures are indissolubly linked with life along the Sepik. With tradition a powerful factor in<br />

their understanding of the world and, by extension, their aesthetics, the tribes of the Sepik incorporate<br />

new elements into tradition, adapting their daily life to new needs that may arise.<br />

Each village has a ritual space – the Haus Tambaran or Spirit House (House of the Ancestors Spirits) –<br />

which is adorned with a plethora of masks, reliefs, sculptures of female figures with exaggerated fertility<br />

symbols and paintings of local myths, oral traditions and religious customs. Many rituals are held in the<br />

Spirit House and the preparations prior to their performance are sacred for the inhabitants. The building<br />

itself is imposing: it is usually made from bamboo with a straw roof and often reaches a height of 25<br />

metres, dominating the whole region around the hamlet and the surrounding forest. Traditionally only<br />

Sepik warriors were permitted to step over the threshold of such a sacred space, and the punishment for<br />

violating this rule was death. This is where the coming-of-age rites for young men are held, during which<br />

the form of a crocodile is cut into their skin as a symbol of their masculine strength. The wounds are then<br />

covered in mud to avoid any infections.<br />

The celebrated art of the Sepik is believed by specialist scholars to be of particular importance, not<br />

simply because of its intricate style and great beauty but also for its cultural meaning. Primarily religious<br />

in its significance, this art still today has a leading position in the religious life of the river tribes. In their<br />

belief system, the spirits of the dead ancestors continue to participate in the social life of the community.<br />

And as living entities, they get angry, are satisfied, give help and seek revenge. The priest-magicians are<br />

often required to perform sacrifices in order to appease them or to attain their assistance for a successful<br />

harvest, fishing trip or battle.<br />

Christian church, Sepik Protective sheats for men’s House interior, Sepik Spirit House Preparing saksak flour<br />

Women of a Sepik tribe<br />

Rainforest, Sepik Initiation procedure Sepik river Wooden masks, Sepik<br />

genital organs

98

101

102

105

106

109

111

112

114

116

119

120

123

125

126

129

131

133

135

137

138

THE HIGHLANDS<br />

Mount Hagen Sing-sing Annual Cultural Festival<br />

Arriving at the capital of Port Moresby I then travelled by air to Mount Hagen, the commercial<br />

and administrative capital of the Western Highlands. Here, at an altitude of approximately 1,500<br />

metres in the beautiful Waghi valley, is the first settlement that came into contact with the Western<br />

world and which was incorporated into the international community in 1930. I should note here<br />

that all my journeys within New Guinea were done by sea or in small aircrafts, as there is as yet no<br />

decent road network. The country’s capital is not connected by road to any other town or village;<br />

all roads end at its outskirts thus creating a profound feeling of exclusion as well as anticipation for<br />

what exists out there.<br />

The small single-engine plane had only eight places and the seats of an old bus. It flew over<br />

the dense vegetation of New Guinea at a low altitude, offering an impressive view of the jungle<br />

and the never-ending mountain ranges. But, some strange sounds that could be heard from all<br />

around, the age of the pilot, who was no older than twenty five and the news that a similar aircraft<br />

had fallen a few hours earlier with the loss of twelve lives, made me fell unsafe, especially when<br />

the young pilot attempted to assure me that I had nothing to be frightened of as our plane was<br />

“very strong” and had not had any serious breakdowns since 1970! I thought to myself that since<br />

this festival is considered one of the 1000 places to see before you die then it was worth the risk. In<br />

the end everything went fine, on this flight and on the many subsequent flights. I really did enjoy<br />

the unique experience of the small airports, the conversations with the pilots without any barrier<br />

between us as well as the landings on the small muddy airstrips where the natives welcomed us<br />

enthusiastically. Because technology is unfamiliar to them they are still impressed by aeroplanes<br />

and helicopters, and treat them with a sense of awe and wonder, representing them as birds or fish<br />

with a marvellous colourful polyphony. One cannot but be moved by the way in which they paint<br />

them in their folk art, by the unbelievable innocence and childish surprise that impregnate their<br />

every colourful image.<br />

It is very difficult for one to describe the intensity of the great annual festival: Thousands of<br />

representatives from over 150 tribes from every corner of the island gather for a stunning event<br />

in which intense colour, flamboyant costumes, esoteric dances and their percussion music play<br />

the lead roles. The tickets for entering the festival site are exorbitant, unattainable for most of the<br />

population, which is obliged to remain on the other side of the event walls. Only tourists and a<br />

few important members of the local society are permitted to watch the Sing-sing, this multiethnic<br />

carnival, this impressive display, from up close. The warriors pay particular attention to how they<br />

paint their faces in the special colours and motifs of each tribe. Delicate, precise lines are drawn on<br />

the skin with thin sticks of wood which they use like a painter’s brush. Every action here takes on a<br />

ritual character and is performed slowly and very carefully. The colours are made from plant pollen<br />

mixed with water or saliva and each warrior paints his own face except for the final brushstrokes,<br />

which are done by a fellow warrior.<br />

Finally, the insertion of colourful plumes into their caps is for the residents of the Highlands<br />

a true art form. Each tribe associates qualities such as bravery, dedication, perceptiveness, etc.<br />

with specific birds, the plumes of which are used as decoration, thus extolling and, to a degree,<br />

appropriating these qualities. All these colourful masses, adorned with the plumes of birds of<br />

paradise and shells from the Pacific Ocean, the faces painted in yellow or red, the pagan masks, the<br />

weapons that clank threateningly and the war cries, fill the festival space so suffocating, right to the<br />

edges, that you imagine there will be an explosion of civilisation and history.<br />

In reality, the event was begun by the first Australian colonialists in their attempt to limit the<br />

permanent conflicts between the tribes, giving them the opportunity to meet within a peaceful<br />

context of rivalry and gentle competition. Soon thousands of participants began to compete<br />

annually for cash prizes. Until recently, and despite the wishful thinking of the organisers, the<br />

Member of the Huli tribe<br />

Sing-sing festival Women of Asamuga tribe Head decoration with one leaf<br />

Face painting<br />

Mud men dancing<br />

Local airport<br />

Αναπαράσταση κηδείας

THE HIGHLANDS<br />

Mount Hagen Sing-sing Annual Cultural Festival<br />

event functioned less as a peaceful intervention and more as an opportunity for further conflict as<br />

the representatives of the Huli, with their ornamental costumes, colourful faces and dramatic war<br />

dance almost always won the competition’s cash prize, outraging the other tribes. This problem<br />

was resolved a few years ago when the organisers decided that the prize would be equally shared<br />

amongst all the participants. Nonetheless, the winners continue to enjoy the respect of all and an<br />

increase in the esteem of their tribe.<br />

During the festival I saw almost all the tribes of the Papua in their official costumes, their disguises<br />

or their war dress. It would be impossible for me to describe them all here. Among them, I surely<br />

admired the Asaro, or Mudmen with their frightening “mud” masks who had once, according to<br />

the myth, by chance covered their bodies with mud from the River Asaro during a battle and in<br />

this way frightened their enemies so much that, thinking them to be forest spirits, they fled. They<br />

later made these frightening masks so that they would not need to cover their faces with river mud,<br />

which they believed to be poisonous. Solely a warrior tribe, all their dances represent battles.<br />

Moreover, the women of the Asamuga tribe are among the most impressive figures at the sing-sing.<br />

The large shells, the so-called kina, are believed to protect them from danger, whilst the wonderful<br />

feathers in their hair declare their social status and their husband’s power. All these tribes and many<br />

more, groups of people dressed uniformly in their tribal costumes, were singing, dancing and also<br />

performing ritual reconstructions: I shall never forget the gruesome reconstruction of a funeral during<br />

which the women covered their bodies with clay as a sign of mourning whilst the coffin contained the<br />

dead body of a small boy, wrapped in moss.<br />

The spectacle is difficult to describe – wherever I turned my head there was something new to<br />

see. And it was truly a unique feeling to know that what was happening in front of my eyes was not a<br />

museum piece, nor was it the revival of some forgotten tradition, a picturesque recreation to entertain<br />

tourists; the Papua often dress in this way even today and many tribes continue to perform the same<br />

mystery rituals prior to battle. They even wear their shells to indicate their wealth and social class, and<br />

bequeath some of their jewellery as leadership emblems or markers of supernatural powers.<br />

I was also impressed by the Skeleton Men of the Bugamo tribe, who paint the human skeleton<br />

onto their bodies. This is still a daily practice, before a hunt or the battle that is today waged with<br />

arrows and javelins. I enjoyed the impressive colourful Huli warriors, the tribe with the strange<br />

wigs, the plumes of birds of paradise and the peculiar appearance, as well as the tribes of the River<br />

Sepik and the various magical healers. Unique were the representatives of the Rakapos tribe, with<br />

their large black hats which, in combination with their black painted faces, aiming at terrifying<br />

into the enemy during the hour of battle. These hats are supported by a frame that the Rakapos<br />

construct with grass, moss and tufts of their hair.<br />

Mud men<br />

Skeleton Μen Rakapos tribe Tribe head, Mt Hagen

146

148

151

153

155

157

158

161

162

165

166

169

171

173

175

177

179

181

183

184<br />

185

186

188

191

193

195

196

199

201

203

205

206

208

211

212

215

216

219

220

223

224

226

228

230

233

234

237

PACIFIC OCEAN<br />

Madang and the surrounding islands<br />

Madang is a province on the country’s north coast, with a length that reaches<br />

approximately 300 kilometres and a width of 160 kilometres, one side facing onto<br />

the Bismarck Sea, whilst in the hinterland are some of the island’s tallest peaks,<br />

with tropical forests and verdant valleys. Many of the Bismarck Archipelago’s<br />

smaller islands belong to this province, some of which are volcanic. The last<br />

volcanic eruption was only in 2010.<br />

Over its great territory the province is home to a significant number of Papua<br />

tribes and for this reason a large linguistic diversity can also be found – over<br />

200 languages are spoken here. The province’s capital is also called Madang, and<br />

it is built around a picturesque port surrounded by imposing and inaccessible<br />

mountains – “the most beautiful town of the Pacific Ocean,” according to many of<br />

its visitors. Madang’s coastline, its tropical vegetation and its many parks certainly<br />

distinguish it from the country’s other towns.<br />

obliging the inhabitants even today to adorn their formal traditional costumes<br />

with parrot plumes.<br />

The first contact that the people of Madang had with the Western world came<br />

in 1871. Certain areas, however, remained isolated and relatively untouched by<br />

European influence. It is precisely for this reason, the distinctive terrain, that<br />

there are great cultural differences between the various tribes. Even so, great<br />

similarities can be seen with a tribe in another of the country’s provinces, namely<br />

the riverside culture of the Ramu, which has developed along the river of the same<br />

name, and the culture of the Sepik, as they have very similar art techniques and<br />

relief sculpture styles.<br />

For 6,000 years now sailors, primarily from the Taiwan region, have crossed the<br />

Bismarck Sea and come ashore on the coasts of Madang, leaving their traces on the<br />

Austronesian languages that are encountered in some of the coastal villages, dotted<br />

in amongst the villages that speak the dialects of Papua New Guinea. This contact<br />

with other people helped the coastal tribes of this region at least to develop trade<br />

from ancient times: the goods they exchanged were pots, salt, stone axe blades,<br />

shells, plumes from birds of paradise and carved wooden vessels. The plumes in<br />

particular were thought to be of great value as they are quite rare in Madang, thus<br />

Cocoa pod<br />

Madang port Cassowary bird Small Pacific island Playing in the ocean<br />

Coast in the Pacific<br />

Tropical forest Madang village Port Moresby museum Islands in the Pacific

241

242

245

247

249

250

252

255

256

258

261

262

264

266

269

270

273

274