PAPUA

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

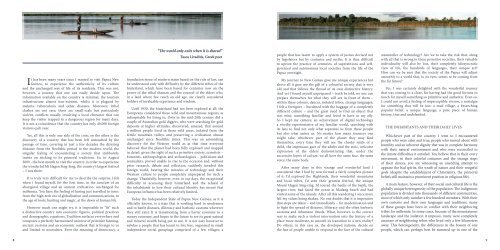

It has been many years since I wanted to visit Papua New<br />

Guinea, to experience the authenticity of its culture<br />

and the unchanged way of life of its residents. Τhis was not,<br />

however, a journey that one can easily decide upon. The<br />

information available on the country is minimal, the tourism<br />

infrastructure almost non-existent, whilst it is plagued by<br />

malaria, tuberculosis and other diseases. Moreover, tribal<br />

clashes are not rare; these are small-scale but particularly<br />

violent, conflicts usually involving a local character that can<br />

keep the visitor trapped in a dangerous region for many days.<br />

It is not a coincidence that the country has only 40,000 foreign<br />

visitors each year.<br />

Yet, all this is only one side of the coin; on the other is the<br />

discovery of a country that has been left untouched by the<br />

passage of time, covering in just a few decades the dizzying<br />

distance from the Neolithic period to the modern world, the<br />

singular feeling of encountering a society that stubbornly<br />

insists on sticking to its primeval traditions. So, in August<br />

2009 –the best month to visit the country in order to experience<br />

the wonderful Mt Hagen Sing-Sing, the country’s largest festival<br />

– I was there.<br />

It is truly very difficult for me to describe the surprise I felt<br />

when i found myself, for the first time, in the sanctum of an<br />

aboriginal village and an ancient civilisation, unchanged for<br />

millennia. You have the feeling of having just travelled in time:<br />

from the high-tech era of globalisation and communications, to<br />

the age of tools, hunting and magic, at the dawn of human life.<br />

However much one might try, it is impossible to “fit” such<br />

a distinctive country into economic figures, political practices<br />

and demographic equations. Tradition surfaces everywhere and<br />

composes a perfectly harmonised universe of primitive farming,<br />

ancient customs and an economic outlook that is foreign to us<br />

and limited to necessities. Even the meaning of democracy, a<br />

“The world only exits when it is shared”<br />

Tasos Livaditis, Greek poet<br />

foundation stone of modern states based on the rule of law, can<br />

be understood only with difficulty by the different tribes of the<br />

hinterland, which have been based for centuries now on the<br />

power of the tribal shaman and the counsel of the elders who,<br />

in a land where few reach an old age, are clearly considered<br />

holders of invaluable experience and wisdom.<br />

Until 1930, the hinterland had not been explored at all; the<br />

Europeans considered these wild and mountainous regions as<br />

inhospitable for living in. Only in the mid-20th century did a<br />

couple of Australian gold diggers, who were searching for gold<br />

deposits at higher altitudes, discovered, amazed, that around<br />

a million people lived in these wild areas, isolated from the<br />

fertile mountain valleys and preserving a civilisation almost<br />

unchanged since Neolithic times. This was an astonishing<br />

discovery for the Western world as at that time everyone<br />

believed that the planet had been fully explored and mapped<br />

in detail: given the sight of such a primitive society, scientists –<br />

botanists, anthropologists and archaeologists – politicians and<br />

journalists, proved unable to rise to the occasion and, without<br />

prior research, debate and reflection, suddenly invaded this<br />

foreign world, bearing the miracles of technology and their<br />

Western culture to people completely unprepared for such a<br />

change. Thankfully, however, even in our days, the exceptional<br />

difficulty in accessing their hinterland and the refusal of<br />

the inhabitants to lose their cultural identity has meant that<br />

European influence has been relatively limited.<br />

Today the Independent State of Papua New Guinea, as it is<br />

officially known, is a state that is working hard to modernise<br />

and to battle diseases, illiteracy and barbaric customs wherever<br />

they still exist. It is transitioning from a barter economy to a<br />

money economy, and hopes in the future to see its great natural<br />

and mineral wealth being put to use. It is not easy however to<br />

subdue a people that has learnt to live free, organised in small<br />

independent social groupings comprised of a few villages; a<br />

people that has learnt to apply a system of justice devised not<br />

by legislators but by centuries and myths. It is thus difficult<br />

to uproot the practice of centuries, of superstitions and selfgoverned<br />

and autonomous local societies from the life of the<br />

Papua overnight.<br />

My journey to New Guinea gave me unique experiences but<br />

above all it gave me the gift of a colourful society that is very<br />

old and that follows the thread of its own distinctive history.<br />

And yet I found myself unprepared – truth be told, no one can<br />

prepare themselves for what they will see in front of them –<br />

within these colours, dances, isolated tribes, strange languages;<br />

I felt a foreigner – burdened with the baggage of a completely<br />

different culture – and the great need to find an object that<br />

was mine, something familiar and loved to have as my ally.<br />

So I kept my camera; an achievement of digital technology<br />

a worthy representative of my familiar world, searching with<br />

its lens to find not only what separates us from these people<br />

but also what unites us. No matter how many journeys one<br />

might take, whichever part of the planet they may find<br />

themselves, every time they will see the cheeky smile of a<br />

child, the impetuous gaze of the adults and the stoic, welcome<br />

expression of the elders demonstrating that, under the<br />

successive layers of culture, we all have the same face, the same<br />

voice, the same body.<br />

After many days in this strange and wonderful land I<br />

considered that I had by now formed a fairly complete picture<br />

of it: I’d explored the Highlands, their wonderful mountains<br />

and local tribes, I’d seen their greatest festival, the unique<br />

Mount Hagen Sing-sing, I’d toured the banks of the Sepik, the<br />

largest river, had faced the ocean at Madang beach and had<br />

visited some of the islands. After all this wandering I once more<br />

felt my values being shaken. No one doubts that it is imperative<br />

that steps are taken – and immediately – for modernisation and<br />

to fight the spread of diseases, illiteracy and the often barbaric<br />

customs and inhumane rituals. What, however, is the correct<br />

way to make such a violent intervention into the history of a<br />

place more moderate, to smooth its transition to a new reality?<br />

Do others, in this case us, the developed nations; decide on<br />

the fate of people unable to respond in the face of the cultural<br />

steamroller of technology? Are we to take the risk that, along<br />

with all that is wrong in these primitive societies, their valuable<br />

individuality will also be lost, their completely idiosyncratic<br />

view of life, the hundreds of languages, their unique art?<br />

How can we be sure that the society of the Papua will adjust<br />

smoothly to a world that, to its eyes, seems to be coming from<br />

the far future?<br />

Yes, I was certainly delighted with the wonderful journey<br />

that was coming to a close, for having had the good fortune to<br />

touch for myself something so primitive and authentic. Even so,<br />

I could not avoid a feeling of imperceptible sorrow, a nostalgia<br />

for something that will be lost: a mud village, a beseeching<br />

popular belief, a unique language; a pure piece of human<br />

history, true and undefended.<br />

THE INHABITANTS AND THEIR DAILY LIVES<br />

Whichever part of the country I went to I encountered<br />

people who were calm and true; people who moved about with<br />

humility and an inherent dignity that was in complete harmony<br />

with their natural environment and who were reconciled to<br />

the innate difficulties it entailed. You believe that in their every<br />

movement, in their colorful costumes and the strange steps<br />

of their dances, you are witnessing an unending attempt to<br />

appease the bad spirits, the wrath of nature and their vengeful<br />

gods (despite the establishment of Christianity, the primeval<br />

beliefs still maintain a prominent position in religious life).<br />

A main feature, however, of their social and cultural life is the<br />

globally unique heterogeneity of the population. The indigenous<br />

population is divided into thousands of different communities,<br />

most of which only number a few hundred members. With their<br />

own customs and their own languages and traditions, many<br />

of these groups have been in conflict with their neighboring<br />

tribes for millennia. In some cases, because of the mountainous<br />

landscape and the isolation it imposes, many were completely<br />

unaware of neighboring tribes who lived only a few kilometers<br />

away. This heterogeneity, the differences in the bosom of one<br />

people, which can perhaps best be summed up in one of the<br />

8 9