Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

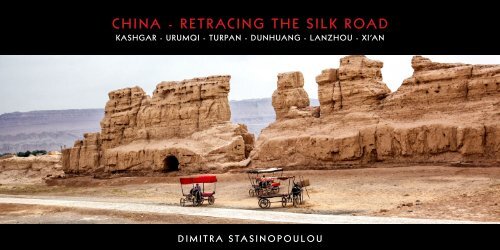

<strong>CHINA</strong> - <strong>RETRACING</strong> <strong>THE</strong> <strong>SILK</strong> <strong>ROAD</strong><br />

KASHGAR - URUMQI - TURPAN - DUNHUANG - LANZHOU - XI’AN<br />

DIMITRA STASINOPOULOU

<strong>CHINA</strong> - <strong>SILK</strong> <strong>ROAD</strong> MAP<br />

URUMQI<br />

DUNHUANG<br />

URUMQI<br />

TURPAN<br />

KASHGAR<br />

KASHGAR<br />

DUNHUANG<br />

LANZHOU<br />

Beijing<br />

LANZHOU<br />

XI’AN<br />

TURPAN<br />

XI’AN

<strong>THE</strong> <strong>SILK</strong> <strong>ROAD</strong> is the world’s oldest, and most<br />

historically important overland trade route. For<br />

over 2000 years, traders and merchants travelled<br />

the deserts of central Asia exchanging goods<br />

between the Chinese empire and the rest of the<br />

world. As a result, the oases of the desert sprang<br />

up into dynamic cities. A vast network of interconnected<br />

caravan routes that stretched for over 6,500<br />

km, enabled the exchange of products and ideas<br />

between China and Europe, Persia, Egypt, India<br />

and Mesopotamia.<br />

The Silk Road remains one of the world’s most<br />

legendary journeys, full of dusty desert roads and<br />

ancient towns immortalized in the accounts of<br />

Marco Polo. Desert landscapes stretch out seemingly<br />

endlessly along this ancient crossroads of civilization,<br />

broken up only by occasional oasis settlements.<br />

The legacy of this trade route has shaped<br />

the region’s multiculturalism, home as it is to several<br />

ethnicities, religions and languages.<br />

The road got its name from the lucrative Chinese silk<br />

trade along it, which began during the Han Dynasty<br />

(206 BC – 220 AD) largely through the missions<br />

and explorations of Zhang Qian, a Chinese official<br />

and diplomat who served as an imperial envoy to<br />

the world outside of China. He was the first official<br />

diplomat to bring back reliable information about<br />

Central Asia to the Chinese imperial court, then<br />

under Emperor Wu of Han, and played an important<br />

pioneering role in the Chinese colonization and<br />

conquest of the region now known as Xinjiang. In<br />

essence, his missions opened up to China the many<br />

kingdoms and products of a part of the world then<br />

unknown to the Chinese.<br />

The Ancient Silk Road started at Changan (today<br />

Xi’an) that was the capital at the time, then it reached<br />

Dunhuang through Lanzhou, where it was divided<br />

into three: the Southern, the Central Route and the<br />

Northern Route. The three routes spread all over the<br />

Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, and then they<br />

extended as far as Pakistan, India, Byzantine Empire<br />

and even the Roman Empire.<br />

The photographs that follow were taken in the so<br />

called North Road i.e. Xian, Lanzhou, Dunhuang,<br />

Turpan, Urumqi and finally to the last ancient oasis<br />

town of Kashgar, the last place the ancient silk road<br />

traders stayed before heading east across the brutal<br />

Taklamakan Desert on their way to the Middle East<br />

(or, for those traders heading the other way, Kashgar<br />

was the first bit of civilization they’d seen in months<br />

as they left the desert and arrived in China). Kashgar<br />

was an important center that led to Samarkand, the<br />

Caspian Sea and India.<br />

Although maritime transport had an influence on<br />

the route, many westerners, Chinese envoys and<br />

caravans travelled along this ancient trade route.<br />

However, the historically important route could not<br />

contend with expansion in the field of navigation<br />

which assisted its demise.<br />

In history, many renowned people left their traces<br />

on the most historically important trade route,<br />

including eminent diplomats, generals and great<br />

monks. They crossed desolate deserts and the<br />

Gobi, passed murderous prairies and went over the<br />

freezing Pamirs to finish theirs missions or realize<br />

their beliefs. Many great events happened on this<br />

ancient road, making the trade route historically<br />

important. A great number of soldiers gave their<br />

lives to protect it. These are some of the reasons the<br />

road is still a time-honored treasure.<br />

HISTORY OF <strong>THE</strong> <strong>SILK</strong> <strong>ROAD</strong><br />

The Silk Road began around 329 BCE, when Alexander<br />

the Great conquered all of the known world,<br />

built the City of Alexandria Eschate and promoted<br />

trade to the east. By this time, Persia had become a<br />

cultural crossroads in Asia with influences from India<br />

and the Greeks. Over time this region, just south<br />

of Karakorum’s ranges, was conquered by various<br />

armies, including those from Syria and Parthia.<br />

Soon, the Yuezhi, from the northern border of the<br />

Taklamakan desert, arrived, after being driven<br />

out of their home by the Xiongnu, who came to be<br />

known as the Huns. The Yuezhi came as converts to<br />

Buddhism. They became known as the Kushan and<br />

their culture was referred to as the Gandhara.<br />

Their culture adopted not only the Buddhism of<br />

the Peshawar region but also the introduced Greek<br />

culture brought by Alexander’s army. Notably,<br />

the Kushan were the first Buddhists to depict the<br />

Buddha in human form.<br />

To the east of the route, Qin Shi Huangdi unified<br />

China to found the Qin Dynasty. Although the Qin<br />

seemed to introduce brutal reforms, the Chinese<br />

language began to become standardized. This<br />

unified empire’s capital was Xi’an. Prior to the Qin<br />

unification, the Xiongnu invaded from the north<br />

more frequently. The northern Chinese states<br />

attempted to thwart these invasions by constructing

walls. Post unification, the Qin worked to fill the gaps<br />

in the various sections of the walls. This build up<br />

signifies the beginnings of the Great Wall of China.<br />

The Qin Dynasty lasted a mere fifteen years and was<br />

succeeded by the Han Dynasty. The Han continued<br />

the construction of the Great Wall. During this<br />

time, the Han became aware that the Xiongnu had<br />

driven the Yuezhi even further west. A recognizance<br />

mission was arranged by the Han in the hope<br />

of an alliance with the Yuezhi against the Xiongnu.<br />

The Han delegations returned home with different<br />

objects and artwork, especially religious art of the<br />

Gandhara. Even then, some Chinese silk and other<br />

goods were slowly reaching the Roman-conquered<br />

Greeks. Most likely these goods were passed<br />

through the hands of individual merchants.<br />

Inevitably, where money can be made, nefarious<br />

activity will develop. The Han soon found problems<br />

occurring along the trade routes. Bandits took to<br />

ransacking caravans as they passed along the Gansu<br />

corridor. Defending their goods caused merchants<br />

extra cost. As the caravans moved further from the<br />

center of the capital, the Han faced the difficulty<br />

of protecting its goods. Forts and walls helped to<br />

bridge this security gap.<br />

The Silk Road did not exclusively deal in silk. Many<br />

goods were traded along the routes. Ivory, gold,<br />

animals and plants were among other commodities.<br />

Of course, silk was what amazed those in the<br />

West. Silk naturally absorbs dye, so that the colors<br />

come out vivid and deep.<br />

Eastward headed caravans brought gold, ivory,<br />

precious stones and metals to China. Westward caravans<br />

carried ceramics, jade, bronze and iron. Most<br />

of these materials did not follow a direct route. They<br />

were often traded repeatedly between different<br />

posts. The middleman controlled each small market<br />

along the way, so that, by the time goods reached<br />

their destination, the price was exorbitant.<br />

Trade on the Silk Road was a significant factor in<br />

the development of the civilizations of China, India,<br />

Persia, Europe and Arabia. Though silk was certainly<br />

the major trade item from China, many other goods<br />

were traded, various technologies, religions and<br />

philosophy.<br />

The great story of the Silk Road is that Buddhism<br />

travelled on it, from India. It is said that a Han<br />

Emperor named Mingdi had a dream of a golden<br />

figure, and his advisers said that the figure was the<br />

Buddha - the God of the West. In 68 AD, Mingdi sent<br />

Cai Yin to Central Asia to learn about this religion.<br />

Cai Yin brought back Buddhist scriptures and two<br />

Buddhist monks. Buddhism became popular, and<br />

people built the big ancient Buddhist temple sites<br />

associated with the Silk Road.<br />

Christianity even saw an early growth along the<br />

Silk Road. A sect known as the Nestorians was<br />

driven out of the Roman Church in the 5 th century<br />

CE. Its adherents settled in Persia. Within two centuries,<br />

their faith spread to Changan. It survived until<br />

the 14 th c.<br />

The main traders during antiquity were the Indian<br />

and Bactrian traders, from the 5 th to the 8 th century<br />

the Sogdian traders and afterward the Arab and<br />

Persian traders. The dry climate has preserved many<br />

ruins, while many ethnic groups make their home in<br />

this part of China, often still living a lifestyle like that<br />

of their great grandfathers.<br />

When Arabs attacked Central Asia in the 700s, Islam<br />

replaced Buddhism as the major religion. The Silk<br />

Road was into disuse after the Tang Dynasty fell in<br />

the year 907. Then Mongolians conquered China<br />

and most of Asia and established the Yuan Dynasty<br />

(1279-1368) in China. In 1271, Kublai Khan established<br />

a powerful Mongol Empire – Yuan Dynasty<br />

(1271-1368) at Dadu (the present Beijing).<br />

The Mongol Empire destroyed a great number<br />

of toll-gates of the Silk Road; therefore passing<br />

through the historic trade route became more<br />

convenient, easier and safer than ever before.<br />

The Mongolian emperors welcomed the travelers<br />

of the West with open arms, and appointed some<br />

foreigners high positions, for example, Kublai<br />

Khan gave Marco Polo a hospitable welcome and<br />

appointed him a high post in his court. At that time,<br />

the Mongolian emperor issued a special VIP passport<br />

known as “Golden Tablet” which entitled holders<br />

to receive food, horses and guides throughout the<br />

Khan’s dominion. The holders were able to travel<br />

freely and carried out trade between East and the<br />

West directly in the realm of the Mongol Empire.<br />

‘Silk Road’ is in fact a relatively recent term, and<br />

for the majority of their long history, these ancient<br />

roads had no particular name. In the mid-19 th<br />

century, the German geologist, Baron Ferdinand<br />

von Richthofen, named the trade and communication<br />

network Die Seidenstrasse (the Silk Road), and

the term, also used in the plural, continues to stir<br />

imaginations with its evocative mystery.<br />

<strong>SILK</strong> PRODUCTION AND <strong>THE</strong> <strong>SILK</strong> TRADE<br />

Silk is a textile of ancient Chinese origin, woven<br />

from the protein fibre produced by the silkworm<br />

to make its cocoon, and was developed, according<br />

to Chinese tradition, sometime around the year<br />

2,700 BC.<br />

Regarded as an extremely high value product, it<br />

was reserved for the exclusive usage of the Chinese<br />

imperial court for the making of cloths, drapes,<br />

banners, and other items of prestige. Its production<br />

was kept a fiercely guarded secret within China for<br />

some 3,000 years, with imperial decrees sentencing<br />

to death anyone who revealed to a foreigner the<br />

process of its production. Tombs in the Hubei province<br />

dating from the 4 th and 3 rd centuries BC contain<br />

outstanding examples of silk work, including<br />

brocade, gauze and embroidered silk, and the first<br />

complete silk garments.<br />

The Chinese monopoly on silk production however<br />

did not mean that the product was restricted to the<br />

Chinese Empire – on the contrary, silk was used as<br />

a diplomatic gift, and was also traded extensively,<br />

first of all with China’s immediate neighbours,<br />

and subsequently further afield, becoming one of<br />

China’s chief exports under the Han dynasty (206 BC<br />

–220 AD). Indeed, Chinese cloths from this period<br />

have been found in Egypt, in northern Mongolia,<br />

and elsewhere.<br />

At some point during the 1 st century BC, silk was<br />

introduced to the Roman Empire, where it was<br />

considered an exotic luxury and became extremely<br />

popular, with imperial edicts being issued to control<br />

prices. Its popularity continued throughout the<br />

Middle Ages, with detailed Byzantine regulations<br />

for the manufacture of silk clothes, illustrating its<br />

importance as a quintessentially royal fabric and an<br />

important source of revenue for the crown.<br />

Additionally, the needs of the Byzantine Church for<br />

silk garments and hangings were substantial. This<br />

luxury item was thus one of the early impetuses in<br />

the development of trading routes from Europe to<br />

the Far East.<br />

XINJIANG UYGHURS AUTONOMOUS REGION<br />

URUMQI, TURPAN, KASHGAR<br />

A territory in western China that accounts for onesixth<br />

of China’s land and is home to about twenty<br />

million people from thirteen major ethnic groups,<br />

the largest of which (more than eight million) is the<br />

Uyghurs, a predominantly Muslim community with<br />

ties to Central Asia.<br />

Xinjiang, about the size of Iran, is divided into<br />

the Dzungarian Basin in the north and the Tarim<br />

Basin in the south by a mountain range. Xinjiang<br />

shares borders with Mongolia, Russia, Kazakhstan,<br />

Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India,<br />

and the Tibet Autonomous Region and is China’s<br />

largest administrative region.<br />

Steppes, deserts and mountains cover most of<br />

Xinjiang and it is the country’s most westerly region.<br />

The largest ethnic group are the Muslim, Turkish<br />

speaking Uyghurs. The region has had an intermittent<br />

history of autonomy and occasional independence,<br />

but was finally brought under Chinese control<br />

in the 18 th century.<br />

Known to the Chinese as Xiyu (“Western Regions”)<br />

for centuries, the area became Xinjiang (“New<br />

Borders”) upon its annexation under the Qing<br />

(Manchu) dynasty in the 18 th century. Westerners<br />

long called it Chinese Turkistan to distinguish it<br />

from Russian Turkistan. Its indigenous population<br />

of agriculturalists and pastoralists (principally<br />

Uyghurs) inhabit oases strung out along the mountain<br />

foothills or wander the arid plains in search of<br />

pasturage.<br />

Since the establishment of firm Chinese control in<br />

1949, serious efforts have been made to integrate<br />

the regional economy into that of the country, and<br />

these efforts have been accompanied by a great<br />

increase in the Han (Chinese) population there. The<br />

policy of the Chinese government is to allow the<br />

ethnic groups to develop and maintain their own<br />

cultural identities but ethnic tensions exist, especially<br />

between Uyghurs and Han.<br />

Communist China established the Autonomous<br />

Region in 1955.

KASHGAR<br />

XINJIANG UYGHUR AUTONOMOUS REGION<br />

Kashgar

KASHGAR, or Kashi, is an oasis city with an approximate<br />

population of 350,000. It is the westernmost city<br />

in China, located near the border with Tajikistan and<br />

Kyrgyzstan and has a rich history of over 2,000 years.<br />

Kashgar was, and in some ways still is, the last frontier.<br />

Geologically and politically, Kashgar is the last town on<br />

one of the longest dead ends on the planet. On three<br />

sides, it is shielded by the Karakorum and Pamir mountain<br />

ranges, on the other by the Taklamakan Desert,<br />

whose name translates as ‘The Go In And You Won’t<br />

Come Out Desert’. To get to Kashgar, you can cross over<br />

a 5,600m pass from Pakistan, on probably the world’s<br />

highest-altitude bus route, or take a 3 day, almost nonstop<br />

bus ride through the desert from Urumqi.<br />

Until the 21 st century, it was almost frozen in time, a<br />

living relic of its trading heyday four centuries earlier.<br />

The old section of Kashgar remained much as Marco<br />

Polo found it: an intoxicating, marvelous confluence of<br />

Indian, Persian, Arabian and Chinese cultures. Recent<br />

renovations of the Old Quarter by the Han Chinese<br />

have taken place, resulting in many old mud buildings<br />

being demolished, and residents relocating to newer<br />

buildings that employ modern earthquake and fire<br />

codes. This has caused an outcry among some who<br />

fear ancient ways of life are vanishing. Some steps are<br />

being taken to preserve Kashgar’s ancient relics, but<br />

the forces of modernity march on.<br />

Situated at the foot of the Pamirs (mountains) where the<br />

ranges of the Tien Shan and the Kunlun Mountains join,<br />

Kashgar commanded the historical caravan routes—<br />

notably the famed Silk Road westward to Europe via<br />

the Fergana Valley of present-day Uzbekistan, as well<br />

as routes going south to the Kashmir region and north<br />

to Ürümqi and the Ili River valley.<br />

Located historically at the convergence point of widely<br />

varying cultures and empires, Kashgar has been under<br />

the rule of the Chinese, Turk, Mongol, and Tibetan<br />

empires. The city has also been the site of an extraordinary<br />

number of battles between various groups of<br />

people on the steppes. Now administered as a countylevel<br />

unit of the People’s Republic of China, Kashgar is<br />

the administrative center of its eponymous prefecture<br />

in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.<br />

The Chinese first occupied Kashgar at the end of the<br />

2 nd c BC, taking it from the Yuezhi people, who had<br />

been driven out of Gansu province. Chinese control,<br />

however, did not survive the 1 st century CE, when<br />

the Yuezhi reoccupied the area. After complex waves<br />

of conquest by peoples from the north and east had<br />

swept over the area, the Chinese again conquered it<br />

during the late 7 th and early 8 th centuries under the Tang<br />

dynasty (618–907), but it was always on the farthest<br />

frontier of Chinese control. After 752 the Chinese were<br />

again forced to withdraw, and Kashgar was successively<br />

occupied by the Turks, the Uyghurs (in the 10 th<br />

and 11 th c), the Karakitai (12 th c), and the Mongols (in<br />

1219), under whom the overland traffic between China<br />

and Central Asia flourished as never before. In the late<br />

14 th c, Kashgar was sacked by Tamerlane, and in the<br />

next centuries it suffered many wars. It was finally reoccupied<br />

by the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) in 1755. In the<br />

period from 1862 to 1875, Kashgar first was a center of<br />

the Muslim Rebellion and then became the capital of<br />

the Muslim general Yakub Beg. Another Muslim rebellion,<br />

led by Ma Zhongyang, took place in the area from<br />

1928 to 1937, but was finally suppressed by the provincial<br />

warlord Sheng Shicai with Soviet aid. Control by<br />

the Chinese government was not restored until 1943.<br />

The hospitable Uyghurs in Kashgar are good at both<br />

singing and dancing, their unique musical instruments<br />

and clothes are exotic to visitors. The bustling markets<br />

are packed with distinctively dressed Uyghurs, ambitious<br />

Central Asian traders and veiled Muslim women<br />

on Sundays. Muslim features are visible throughout the<br />

city. A mosque towers high above the mud-thatched<br />

houses. While strolling the city’s alleyways we can have<br />

glimpses through the mud-brick doorways of people<br />

engaged in all manner of ancient arts, including bread<br />

making, metal forging, musical instrument manufacturing<br />

and firing of hand-made tile. The lush green<br />

valley of Kashgar, with tall poplars, is famous for the<br />

cultivation of fruits, grains, cotton and livestock.<br />

Id Kah Mosque, is the biggest mosque in the Region.<br />

On Friday, the holy day for Islam, up to 20,000 people<br />

can squeeze into the mosque and its precincts to face<br />

Mecca and join in the prayers.<br />

Apak Hoja Tomb (also known as the Fragrant Princess<br />

Tomb), has an Islamic-style architecture, where the<br />

beloved concubine of Emperor Qianlong of the Qing<br />

Dynasty (1644-1911), Apak Hoja, was buried.<br />

Still an active trading center, was the last place the Silk<br />

Road traders stayed before heading east across the brutal<br />

Taklamakan Desert on their way to the Middle East (or,<br />

for those traders heading the other way, Kashgar was<br />

the first bit of civilization they’d seen in months as they<br />

left the desert and arrived in China). It is a fascinating<br />

blend of cultures between the Muslim Uyghurs, who<br />

represent about 80% of the area’s population. International<br />

Bazaar, is composed of farmers’ markets, flea<br />

markets, animal markets and meat markets. While the<br />

bazaar is open every day of the week, traders from all<br />

over neighboring countries make the trek into Kashgar<br />

each Sunday to be a part of the main spectacle that<br />

encompasses over 4,000 permanent stalls.<br />

Kashgar’s Sunday livestock market at the edge of the<br />

city, offers a glimpse of the past, with intense buying<br />

and selling of sheep, donkeys, goats, cows and the<br />

occasional camels. Local Uyghur men, dressed in traditional<br />

garb, herd or haggle; when they get hungry, they<br />

just head to the sidelines where various food stalls have<br />

been set up, each cooking a dish made of fresh mutton.

KASHGAR OLD TOWN

KASHGAR TOWN BAZAAR

ID KAH MOSQUE

KASHGAR NEW TOWN

KASHGAR SUNDAY ANIMAL MARKET

TOMB OF APAK HOJA

UPAL VILLAGE

TRADITIONAL UYIGUR DANCING

URUMQI<br />

XINJIANG UYGHUR AUTONOMOUS REGION<br />

Urumqi

URUMQI, the capital of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous<br />

Region in northwest China, is located at the foot of<br />

the Tianshan Mountains. The city’s name in local<br />

language means “fine pasture”. It is located in a fertile<br />

belt of oases along the northern slope of the eastern<br />

Tien Shan range. The area first came under full Chinese<br />

control in the 7 th and 8 th centuries AD. Situated along<br />

the ancient Silk Road, the city became an important<br />

center for caravans on the Silk Road traveling onto the<br />

Ili River Valley from the main route across Turkistan.<br />

Urumqi thus was a major hub on the Silk Road during<br />

China’s Tang Dynasty, having developed a reputation<br />

as an important commercial and cultural center<br />

during the Qing Dynasty. It is quite famous for its<br />

claim as the most inland major city in the world, that<br />

being the farthest from any ocean.<br />

Red Hill is a symbol of Urumqi, owing to its uniqueness.<br />

The body of the mountain, made up of aubergine<br />

rock, has a reddish brown color. It is 1.5km long<br />

and 1km wide from east to west. The city lies in the<br />

shadow of the lofty ice-capped Bogda Peak with vast<br />

Salt Lake to the east, the rolling pine-covered Southern<br />

Hill, the alternating fields and sand dunes of Zunggar<br />

Basin to the northwest.<br />

Less than 1km away, Yamalike Hill stands facing Red<br />

Hill. Legend has it that in ancient times a red dragon<br />

fled from Heavenly Lake and the Heavenly Empress<br />

caught him and sliced him in two with her sword.<br />

Later on, the western part of the dragon turned into<br />

Yamalike Hill and the eastern turned into Red Hill. The<br />

sword turned into the Urumqi River. Oddly enough,<br />

topographic pictures tell us the two hills were once<br />

one and were separated into two parts due to<br />

stratum rupture.<br />

Eventually, ancient legend affected real life. In 1785<br />

and 1786, floods hit Urumqi causing much destruction.<br />

Rumors arose that Red Hill and Yamalike Hill were<br />

growing closer and closer together. Once they met,<br />

the Urumqi River between them would be blocked<br />

and the city would become flooded as the water rose.<br />

Therefore, in 1788 Shang An, the highest military<br />

officer, ordered the Zhen Long (in Chinese, to subdue<br />

the dragon) Pagodas built on both hills. These two<br />

pagodas were made of gray brick, 10.5- meter high<br />

with six sides, nine stories and an octagonal roof.<br />

There are two major ethnic groups, the traditional Han<br />

(3.0 million) and Uyghur (0.25 million). Other ethnic<br />

groups in Urumqi include Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Mongols<br />

and Hui Muslims.<br />

Regardless of ethnicity, most people in Urumqi can<br />

speak some level of Mandarin Chinese, however in<br />

some parts of the city Uyghur, a Turkish language,<br />

is dominant.<br />

The Erdaoqiao Bazaar is the largest in Urumqi. It<br />

is a bustling market filled with fruit, clothing, crafts,<br />

knives, carpets and almost anything that you can<br />

imagine. The old streets around the bazaar are really<br />

worth seeing.<br />

The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region Museum<br />

has collections of silver works of art, stone steles, coins<br />

and currency, ceramics, wooden articles, and paintings,<br />

a broad overview of Chinese civilization along<br />

the Silk Road and local ethnic cultures. One of the highlights<br />

is the well-preserved collection of 4,000-yearold<br />

corpses, unearthed along the Silk Road.<br />

Built in 1953, it has an exhibition hall that covers an<br />

area of about 7,800 square meters. The building is in<br />

Uyghur style, the internal decor having strong ethnic<br />

features. In total there are over 50,000 items in the<br />

collection. These not only represent the ethnic lifestyle<br />

and humanity of the region but also illustrate its<br />

revolutionary spirit.<br />

With such an abundance of items on display, the exhibition<br />

is widely acknowledged for its comprehensive<br />

and informative nature both at home and abroad.<br />

The one relating to folk customs includes costumes,<br />

tools and every day necessities. Together they vividly<br />

illustrate for us the dress, lifestyle, religion, marriage<br />

customs, festivals and other aspects of the colorful<br />

life of the 12 minorities that live in Xinjiang.<br />

The historical relics include carpentries, iron wares,<br />

bronze wares, bright and beautiful brocades, tomb<br />

figures, pottery, coins, rubbings from stone inscriptions<br />

and writings, as well as weapons and so on.<br />

These give an insight into the past and show how the<br />

society of Xinjiang developed. There is even the fossil<br />

of a human head that dates back some 10,000 years.<br />

The display of ancient corpses is fantastic, for it was<br />

in this region that a great number of ancient and<br />

well preserved remains were discovered. These are<br />

quite different from the mummies in Egypt that<br />

were created by skilled embalming procedures; the<br />

corpses here were dried by the particular natural<br />

environment. In all there are twenty-one specimens<br />

in the collection and include men, women, lovers,<br />

and generals. The ‘Loulan beauty’ is among the best<br />

preserved and famous ones. It has a reddish brown<br />

skin, thick eyelashes, charming large eyes, and long<br />

hair. This particular ‘charming’ corpse has survived<br />

for an estimated 4,000 years.

ERDAOQIAO BAZAAR

TURPAN<br />

XINJIANG UYGHUR AUTONOMOUS REGION<br />

Turpan

TURPAN, also known as Turfan or Tulufan, is an<br />

ancient city with a long history. Traces have been<br />

found of humans living there, dating as far back<br />

as 6,000 years ago. The city was known as Gushi<br />

in the Western Han Dynasty (206BC-240AD); and<br />

in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), it got its name<br />

Turpan, which means ‘the lowest place’ in the<br />

Uygur language and ‘the fertile land’ in Turkish.<br />

Lying in the Turpan Basin, the elevation of most<br />

places in the area is below 500 meters, the<br />

lowest elevation in China. The city, which is also<br />

known as Huo Zhou (‘a place as hot as fire’), is the<br />

hottest place in China. It is praised as the ‘Hometown<br />

of Grapes’ and the Grape Valley is a good<br />

place to enjoy hundreds of varieties of grapes.<br />

Turpan has long been the center of a fertile oasis<br />

(with water provided by the Karez canal system)<br />

and an important trade center. It was historically<br />

located along the Silk Road, at which time it was<br />

adjacent to the kingdoms of Kroran and Yanqi. The<br />

name Turfan itself however was not used until the<br />

end of the Middle Ages - its use became widespread<br />

only in the post-Mongol period. The center of the<br />

region has shifted a number of times, from Jiaohe,<br />

10 km to the west of modern Turpan, Gaochang, 30<br />

km to the southeast of Turpan and to Turpan itself.<br />

The Tang dynasty had reconquered the Tarim Basin<br />

by the 7 th c AD and for the next three centuries the<br />

Tibetan Empire, the Tang dynasty, and the Turks<br />

fought over dominion of the Tarim Basin. Tibetans<br />

took control in 792. In 803, the Uyghurs seized<br />

Turfan from the Tibetans. The Uyghur Khaganate<br />

however was destroyed by the Kirghiz and its capital<br />

Ordu-Baliq in Mongolia, sacked in 840. The defeat<br />

resulted in the mass movement of the Uyghurs out<br />

of Mongolia and their dispersal into Gansu and<br />

Central Asia. Many joined other Uyghurs already<br />

present in Turfan.<br />

The Uyghurs established a Kingdom in the Turpan<br />

region with its capital in Gaochang or Kara-Khoja.<br />

The kingdom lasted from 856 to 1389 AD. They were<br />

Manichaean but later converted to Buddhism and<br />

formed an alliance with the rulers of Dunhuang.<br />

The Uyghur State later became a vassal state of the<br />

Kara-Khitans, and then as a vassal of the Mongol<br />

Empire. This Kingdom was led by the Idikuts, or Saint<br />

Spiritual Rulers. The last Idikut left Turpan area in<br />

1284 for Kumul, then Gansu to seek protection of<br />

Yuan Dynasty, but local Uyghur Buddhist rulers still<br />

held power until the invasion by the Moghul Hizir<br />

Khoja in 1389. The conversion of the local Buddhist<br />

population to Islam was completed nevertheless<br />

only in the second half of the 15 th century.<br />

Ancient city of Gaochang (1 st c. BC). An important<br />

point on the Silk Road. The city’s name means<br />

‘the King City’ and was abandoned during the 15 th<br />

century. Divided into three parts the exterior city,<br />

interior city and the palace city with a total area is<br />

about two million square meters. Recalling Pompeii<br />

in scale, this city was lost to the sands of the Gobi for<br />

hundreds of years until recent excavation. It is listed<br />

as a UNESCO World Heritage site.<br />

Ancient city of Jiaohe Kerez (2 nd c. BC). The Jiaohe<br />

is a natural fortress located atop a steep cliff on a<br />

leaf-shaped plateau between two deep river valleys.<br />

From the years 108 BC to 450 AD was the capital of<br />

the Anterior Jushi, concurrent with the Han Dynasty,<br />

Jin Dynasty, and Southern and Northern Dynasties<br />

in China. It was an important site along the Silk Road<br />

trade route leading west.<br />

Turpan’s Flaming Mountains, the hottest place in<br />

China, overshadow the cradle of the Turpan ancient<br />

civilization and oasis agriculture. They provide a<br />

spectacular backdrop to the oases and scenery<br />

of the Turpan area, and have given rise to many<br />

legends and stories.<br />

The Emin Minaret or Imin Ta stands by the Uyghur<br />

mosque. At 44 meters it is the tallest minaret in<br />

China. The minaret was started in 1777 and was<br />

completed only one year later. It was financed by<br />

local leaders and built to honor the exploits of a<br />

local Turpan general, Emin Khoja. The richly textured<br />

sun dried yellow bricks are carved into intricate,<br />

repetitive, geometric and floral mosaic patterns,<br />

such as stylized flowers and rhombuses. This<br />

mixture of Chinese and Islamic features is seen only<br />

in minarets in China.<br />

Turpan Museum is the second largest museum<br />

in Xinjiang, only after Xinjiang Regional Museum.<br />

Being on the route of the famous ‘Silk Road’, Turpan<br />

assembled traders and monks from western and<br />

eastern countries.<br />

It houses more than 5,000 artifacts, archaic<br />

mummies, and many old documents in different<br />

languages. Many of the mummies have been found<br />

in very good condition, owing to the dryness of<br />

the desert and the desiccation it produced in the<br />

corpses. The mummies (1100–500 BCE) share typical<br />

Europoid body features and many of them have<br />

their hair physically intact, ranging in color from<br />

blond to red to deep brown, and generally long,<br />

curly and braided. Their costumes, and especially<br />

textiles, may indicate a common origin with Indo-<br />

European neolithic clothing techniques.

GAOCHANG ANCIENT CITY RUINS

TURPAN TOWN BAZAAR

GRAPE VALLEY

TURPAN FLAMING MOUNTAINS

TURPAN MUSEUM

EMIN MINARET

ANCIENT CITY OF JIAOHE KEREZ

DUNHUANG<br />

GANSU PROVINCE<br />

Dunhuang

DUNHUANG is a county-level city in northwestern<br />

Gansu Province, Western China and in ancient time<br />

it was a major stop on the ancient Silk Road and the<br />

trade center between China and its western neighbors.<br />

It was established as a frontier garrison outpost<br />

by the Han Dynasty Emperor Wudi.<br />

Situated in a rich oasis containing Crescent Lake and<br />

Mingsha Shan (meaning “Singing-Sand Mountain”),<br />

named after the sound of the wind whipping off the<br />

dunes, the singing sand phenomenon. It commands<br />

a strategic position at the crossroads of the ancient<br />

Southern Silk Road and the main road leading from<br />

India via Lhasa to Mongolia and Southern Siberia, as<br />

well as controlling the entrance to the narrow Hexi<br />

Corridor, which led straight to the heart of the north<br />

Chinese plains and the ancient capitals Xian and<br />

Luoyang. At that time, it was the most westerly frontier<br />

military garrison in China. With the flourishing of<br />

trade along the Silk Road, it was prompted to become<br />

the most open area in international trade in Chinese<br />

history. It provided the only access westward for the<br />

Chinese Empire and eastward for western nationalities.<br />

Today it is best known for the Mogao Caves.<br />

During the Tang Dynasty, Dunhuang became the main<br />

hub of commerce of the Silk Road and a major religious<br />

center. As a frontier town, Dunhuang had been occupied<br />

at various times by other non-Han Chinese. After<br />

the Tang Dynasty, the site went into a gradual decline,<br />

and construction of new caves ceased entirely after<br />

the Yuan Dynasty. By then Islam had conquered much<br />

of Central Asia, and the Silk Road declined in importance<br />

when trading via sea-routes began to dominate<br />

Chinese trade with the outside world. During the<br />

Ming Dynasty, the Silk Road was finally officially abandoned,<br />

and Dunhuang slowly became depopulated<br />

and largely forgotten by the outside world. Most of<br />

the Mogao caves were abandoned; the site, however,<br />

was still a place of pilgrimage and was used as a place<br />

of worship by locals.<br />

The Mogao Caves also known as the Thousand<br />

Buddha Grottoes, form a system of 492 temples 25<br />

km southeast of the center of Dunhuang. The caves<br />

contain some of the finest examples of Buddhist<br />

art spanning a period of 1,000 years. The first caves<br />

were dug out in 366 AD as places of Buddhist meditation<br />

and worship. The construction of the Mogao<br />

Caves begun sometime in the 4 th c. According to a<br />

book written during the reign of Tang Empress Wu,<br />

a Buddhist monk named Lè Zūn, had a vision of a<br />

thousand Buddhas bathed in golden light at the site<br />

in 366 AD, inspiring him to build a cave here. From the<br />

4 th until the 14 th century, caves were constructed by<br />

monks as shrines with funds from donors - laborately<br />

painted, the cave paintings and architecture were<br />

serving as aids to meditation, as visual representations<br />

of the quest for enlightenment and as teaching<br />

tools to inform those illiterate about Buddhist beliefs<br />

and stories. They were sponsored by patrons such<br />

as important clergy, local ruling elite, foreign dignitaries,<br />

as well as Chinese emperors. Other caves may<br />

have been funded by merchants, military officers<br />

and locals.<br />

During late 19 th and early 20 th century, Western<br />

explorers began to show interest in the ancient Silk<br />

Road and the lost cities of Central Asia, and those who<br />

passed through Dunhuang noted the murals, sculptures,<br />

and artifacts. The biggest discovery, however,<br />

came from a Chinese Taoist named Wang Yuanlu who<br />

appointed himself guardian of some of these temples<br />

around the turn of the century.<br />

An important cache of documents was discovered in<br />

1900 in the so-called “Library Cave,” which had been<br />

walled-up in the 11 th century. The most famous text<br />

in the library cave, the Diamond Sutra, which dates<br />

to 868 AD, was made using this woodblock printing<br />

technique and is the first complete printed book in<br />

the world. The content of the library was dispersed<br />

around the world, and the largest collections are now<br />

found in Beijing, London, Paris and Berlin. Some of the<br />

caves had by then been blocked by sand and Wang<br />

set about clearing away the sand and made an attempt<br />

at repairing the site. In one such cave, Wang discovered<br />

a walled up area behind one side of a corridor<br />

leading to a main cave. Behind the wall was a small<br />

cave stuffed with an enormous hoard of manuscripts.<br />

In the next few years, Wang took some manuscripts<br />

to show to various officials who expressed varying<br />

level of interest, but in 1904 Wang re-sealed the cave<br />

following an order by the governor of Gansu.<br />

Words of Wang’s discovery drew the attention of a<br />

joint British/Indian group led by Hungarian archaeologist<br />

Aurel Stein who was on an archaeological expedition<br />

in the area in 1907. Stein negotiated with Wang<br />

to allow him to remove a significant number of manuscripts<br />

as well as the finest paintings and textiles for<br />

a fee. He was followed by a French expedition under<br />

Paul Pelliot who acquired many thousands of items in<br />

1908, and then by a Japanese expedition under Otani<br />

Kozui in 1911 and a Russian expedition under Sergei<br />

F. Oldenburg in 1914.<br />

In 1956, the first Premier of the People’s Republic<br />

of China, Zhou Enlai, took a personal interest in the<br />

caves and sanctioned a grant to repair and protect the<br />

site. The Mogao Caves became one of the UNESCO<br />

World Heritage Sites in 1987.

SINGING SAND MOUNTAINS - Sand Dunes of Mingsha

CRESCENT SPRING LAKE (Yueya Quan)

MOGAO CAVES (One Thousand Buddha Caves)

DUNHUANG TOWN - Night Bazaar

LANZHOU<br />

GANSU PROVINCE<br />

Lanzhou

LANZHOU is the capital city of Gansu Province in<br />

northwest China. The Yellow River, the Chinese<br />

Mother River, runs through the city, ensuring rich<br />

crops of many juicy and fragrant fruits. Covering an<br />

area of 1631.6 square kilometers it was once a key<br />

point on the ancient Silk Road.<br />

The history of Lanzhou is tied up with the Silk Road.<br />

The Han Empire (206 BC – 220 AD) rulers wanted<br />

trade and allies and sent Zhang Qian, as an emissary<br />

to western countries, two times about the year 100<br />

BC. He had very long and adventurous journeys that<br />

included being captured for 10 years and escaping.<br />

The Han rulers sent a big embassy with him with<br />

trading goods, and they interested the countries to<br />

the west with trade with China.<br />

On and off for about 1,600 years after 100 BC, the Silk<br />

Road through the Hexi Corridor and Lanzhou was an<br />

important trade route. For centuries, between the<br />

Chinese Empires and Kingdoms in the Far East and<br />

the empires and Kingdoms to the west, the quickest<br />

and safest overland route north of the Himalayan<br />

mountains passed through the town of Dunhuang<br />

at the western end of the Hexi Corridor, though the<br />

Hexi Corridor passage, and then on to Lanzhou. The<br />

Hexi Corridor is about 1,000 kilometers long, and the<br />

towns and rivers were used by traders, troops and<br />

travelers. On both sides of this corridor is inhospitable<br />

terrain. To the south are the Qilian Mountains<br />

and the Tibetan Plateau, and to the north are the<br />

Beishan Mountains and the Gobi desert. For going<br />

between the West and China, the big, long valley<br />

was one of the two main land routes. The other<br />

route called the Southern Silk Road or the Tea Horse<br />

Road went through Yunnan in the far southwestern<br />

corner of China.<br />

Zhongshan Bridge, also called the first bridge over<br />

the Yellow River, lies at the foot of Bai Ta Mountain<br />

and in front of Jin Cheng Pass in Lanzhou city,<br />

the capital of Gansu Province. Before Zhongshan<br />

Bridge was built there were many floating bridges<br />

over the Yellow River, but only one existed for a<br />

relatively long period. This bridge was called Zhen<br />

Yuan Floating Bridge and was made up of more<br />

than 20 ships, tied up by ropes and chains. It floated<br />

on the river in order to help people pass over, but<br />

it was neither solid nor safe enough. Almost every<br />

year floods destroyed the bridge and killed people.<br />

Used for over 500 years, the Zhen Yuan Floating<br />

Bridges was finally retired in 1909, when an iron<br />

bridge was built.<br />

The Gansu Museum houses 75,000 cultural relics,<br />

ranging from fossil to articles of historical and<br />

heritage significance. More than 110 pieces are<br />

rated of first class significance including Gansu<br />

color-painted pottery, and bamboo medication<br />

slips from the Han era.<br />

The most famous piece in the collection from the<br />

Han Dynasty (206BC-220AD) is a bronze Galloping<br />

Horse of Wuwei that is accompanied by an impressive<br />

array of chariots and carriages. Excavated in<br />

1969 in Wuwei County, Gansu Province, the piece<br />

depicts a vigorous horse with long tail waving and<br />

head perking. Its 3 hooves are in the air, galloping<br />

like lightening. What makes this sculpture amazing<br />

is the right back hoof of this galloping horse lands<br />

on the back of a small flying bird. The bird turns<br />

in surprise to look at the big creature on its back.<br />

At the same moment, the horse’s head also turns<br />

slightly in attempt to know what has happened.<br />

The whole statue is honored as the mysterious and<br />

rare treasure in the history of Chinese sculpture art.<br />

Bingling Temple Grottoes are located on the Small<br />

Jishi Hill, about 35 km west of Yongjing County<br />

in Lanzhou City. Bingling means ‘Ten Thousand<br />

Buddhas’ in the Tibetan language.<br />

Being one of the very noted four caves in China, it<br />

is the second to Mogao Caves in respect of artistic<br />

value. It was added to UNESCO World Heritage<br />

List on June 22, 2014. The starting construction<br />

time dates back to the Western Jin Dynasty (265-<br />

316). In the following dynasties, the caves had<br />

been excavated many times. There are now 183<br />

niches, 694 stone statues, 82 clay sculptures and<br />

some 900 square meters’ of murals, which are all<br />

well preserved. Famous for its stone sculptures,<br />

Bingling Thousand Temple Caves stretches about<br />

200 meters on the west cliff in Dasi Gully. With<br />

elegant postures, flying robes and ribbons, the<br />

statues are life-like.<br />

The stone sculptures represent the social situations<br />

and customs during ancient times. In the vicinity of<br />

the caves are green hills, crystal water, grotesque<br />

stones and precipitous cliffs, which adds more<br />

beauty to this artistic site.<br />

One of the biggest surviving carved statues of<br />

Buddha from the Tang Dynasty era (618-907) in<br />

China is the Great Maitreya Buddha, similar to the<br />

Buddhas of Bamiyan and measures 27 tall. It is<br />

similar to bigger giant statues built about 250 years<br />

earlier in Central Asia showing the cultural link with<br />

the region. Their inaccessibility spared them from<br />

destruction during the Cultural Revolution.

LANZHOU TOWN - Yellow River

BINGLING TEMPLE GROTTOES

GANSU MUSEUM

X I ’AN<br />

SHAANXI PROVINCE<br />

XI’AN, one of the oldest cities in China, is the capital of Shaanxi province, located in the northwest<br />

of China, in the center of the Guanzhong Plain. Known as Chang’an (meaning the Eternal City)<br />

before the Ming dynasty, Xi’an is the oldest of the Four Great Ancient Capitals of China, having held<br />

the position under several of the most important dynasties in Chinese history, including Zhou, Qin,<br />

Han, Sui, and Tang.<br />

Xi’an is the starting point of the Silk Road and home to the Terracotta Army of Emperor Qin Shi<br />

Huang. The Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-24AD), which is the third dynasty, setting up its capital<br />

in Xian, constructed its capital – Chang’an on the relics of the Qin’s Xianyang. Once, the city was the<br />

largest one in the world, covering an area of about 36 square kilometers. The famous ‘Silk Road’<br />

which starts from the Chang’an City appeared during the period of Wudi, opening the communication<br />

between China and overseas countries. On the other hand, the emperors carried out a series of<br />

policies to help with people’s rehabilitation. As the eastern terminal of the Silk Road and the site of<br />

the famous Terracotta Warriors of the Qin Dynasty, the city has won a reputation all over the world.<br />

X i ’an<br />

The Terracotta Army (Terracotta Warriors and Horses) are the most significant archeological excavations<br />

of the 20 th century. Work is ongoing at this site, which is around 1.5 km east of Emperor Qin Shi<br />

Huang’s Mausoleum in Lintong, Xian, Shaanxi Province.<br />

Upon ascending the throne at the age of 13 (in 246 BC), Qin Shi Huang, later the first Emperor of all<br />

China, had begun to work for his mausoleum. It took 11 years to finish. It is speculated that many<br />

buried treasures and sacrificial objects had accompanied the emperor in his afterlife. A group of<br />

peasants uncovered some pottery while digging for a well nearby the royal tomb in 1974. It caught<br />

the attention of archeologists immediately. They came to Xian in droves to study and to extend<br />

the digs. They had established beyond doubt that these artifacts were associated with the Qin<br />

Dynasty (211-206 BC). The figures vary in height according to their roles, with the tallest being the<br />

generals. The figures include warriors, chariots and horses. Estimates from 2007 were that the three<br />

pits containing the Terracotta Army held more than 8,000 soldiers, 130 chariots with 520 horses<br />

and 150 cavalry horses, the majority of which remained buried in the pits nearby Qin Shi Huang’s<br />

mausoleum. Other terracotta non-military figures were found in other pits, including officials,<br />

acrobats, strongmen and musicians.

XIAN - Terracotta Warriors and Horses

<strong>THE</strong> GREAT WALL OF <strong>CHINA</strong><br />

<strong>THE</strong> GREAT WALL MAP<br />

Both the Great Wall of China and the Silk Road are symbols of Chinese history. The Great Wall,<br />

constructed between 221 B.C. and A.D. 1644, spans 9,000 km and was built as a line of defense to<br />

protect the country from invaders. The wall was begun in during the Qin dynasty between 221<br />

and 207 B.C. Work continued during the Han dynasty but ceased in A.D. 220 and construction<br />

languished for a thousand years. With the threat of Genghis Khan, the project resumed in 1115.<br />

During the Ming dynasty (1368 to 1644), the wall was reinforced with stone and brick. Despite<br />

the immense building and intimidating size of the wall, it wasn’t enough to keep invaders away.<br />

The Mongols were able to ride right through gaps in the wall, and later, the Manchus overtook<br />

the Ming dynasty by riding through the gates that traitor Gen. Wu Sangui opened.<br />

Around the same time as the Great Wall construction during the Han dynasty, Zhan Qian opened<br />

the Silk Road route to trade with other countries. Routes were extended and trade flourished<br />

during the remainder of the Han dynasty. Wars with the Huns were fought along the Silk Road<br />

to gain control and keep the trade route open during the Han dynasty. After the Mongols gained<br />

power in 1271, the ruler Kublai Khan destroyed most of the toll gates and allowed for easier<br />

travel. Khan welcomed Marco Polo, the great explorer and gave him the right to travel the route<br />

whenever he liked.<br />

The Great Wall is rumored to have been constructed with mud, bricks, stones and bones of<br />

the workers who toiled day after day to build it. The first wall, constructed under Emperor Qin<br />

Shi Huang, was built by hundreds of thousands of political prisoners over the course of 10<br />

years. During the Ming dynasty, when workers were frantic to reinforce the wall to keep out the<br />

Manchus, it is estimated that 2 to 3 million Chinese workers perished. On the Silk Road, Chinese<br />

soldiers lost their lives defending the route from the Huns, mostly during the Han dynasty.<br />

Although they were successful at keeping the Huns at bay, many sacrificed their lives to maintain<br />

the trade route.<br />

Dunhuang<br />

Lanzhou<br />

BEIJING