340249

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

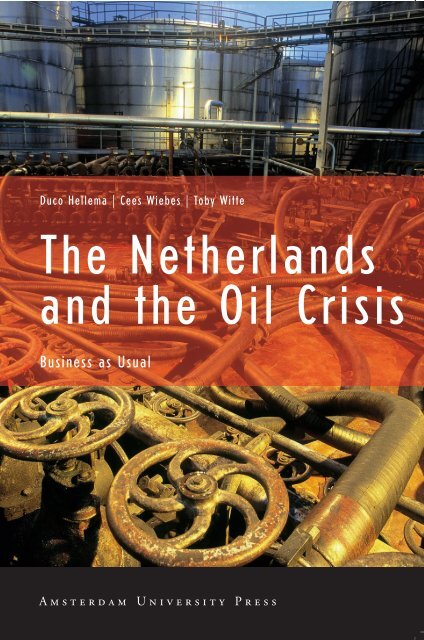

Duco Hellema | Cees Wiebes | Toby Witte<br />

The Netherlands<br />

and the Oil Crisis<br />

Business as Usual<br />

A MSTERDAM U NIVERSITY P RESS

The Netherlands and the Oil Crisis

The Netherlands and the Oil Crisis<br />

Business as Usual<br />

Duco Hellema<br />

Cees Wiebes<br />

Toby Witte<br />

amsterdam university press

The translation of this publication was funded by the Netherlands<br />

Organisation for Scientific Research (nwo).<br />

The Netherlands and the Oil Crisis: Business as Usual is a translation<br />

of Doelwit Rotterdam: Nederland en de oliecrisis, Den Haag: Sdu,<br />

1998.<br />

English translation: Murray Pearson<br />

Cover illustration: © Freek van Arkel/Hollandse Hoogte<br />

Cover design: Sabine Mannel, n.a.p., Amsterdam<br />

Lay-out: Adriaan de Jonge, Amsterdam<br />

isbn 90 5356 485 3<br />

nur 697<br />

© Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 2004<br />

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved<br />

above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into<br />

a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic,<br />

mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written<br />

permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book.

Contents<br />

Foreword 9<br />

1 War in the Middle East 13<br />

The Netherlands and the Middle East 17<br />

Support for Israel 18<br />

Military Support 22<br />

Arms Deliveries 27<br />

Foreign Ministry Denial 31<br />

European Political Cooperation 35<br />

Conclusion 38<br />

2 Difficulties 41<br />

Turf War in The Hague 47<br />

The First Signs 50<br />

The Oil Weapon Brought to Bear 52<br />

Nationalization in Iraq 55<br />

A New Government Statement 56<br />

The Embargo Spreads 58<br />

The De Lavalette Mission 63<br />

The Second Chamber 66<br />

klm 68<br />

Conclusion 71<br />

3 European Divisions 73<br />

The Netherlands and European Integration 74<br />

France 77<br />

Great Britain 79<br />

The Neighbouring ec Countries 81<br />

5

The oecd 83<br />

The ec 84<br />

A Declaration by the Nine 88<br />

Reactions in The Netherlands 92<br />

Conclusion 95<br />

4 Domestic Measures 97<br />

The Den Uyl Cabinet 97<br />

The Importance of Oil 98<br />

Uncertainty 100<br />

Reducing consumption 103<br />

The First Car-Free Sunday 107<br />

Shell Helps 109<br />

The Co-ordination Group 114<br />

Conclusion 115<br />

5 A European Summit 117<br />

The Embargo 117<br />

The Van Roijen Mission 120<br />

An Incident in The Hague 123<br />

The European Community 126<br />

Two Oil Ministers in Europe 131<br />

American Support 134<br />

Divisions within the ec 137<br />

Den Uyl and Van der Stoel 140<br />

Visible or Invisible 144<br />

Copenhagen 150<br />

Conclusion 153<br />

6 Rationing 157<br />

Car-Free Sundays 158<br />

Estimates 160<br />

Export Restrictions 165<br />

Preparations for Rationing 170<br />

The Enabling Act 174<br />

Doubt and Postponement 177<br />

The Cabinet Ploughs on 179<br />

Three Weeks Rationing 181<br />

Conclusion 188<br />

6

7 From Copenhagen to Washington 191<br />

American Leadership 191<br />

Production Limits and Oil Prices 193<br />

The Embargo 195<br />

Oil for Arms 200<br />

An Invitation from Nixon 205<br />

French Obstruction 209<br />

Deliberations in European Political Cooperation 212<br />

The Washington Conference 214<br />

Conclusion 218<br />

8 Sweating it out 221<br />

A Second Letter to King Feisal 222<br />

The Lifting of the Embargo against the usa 225<br />

Plans for a United Nations Conference 227<br />

The Sequel to Washington 231<br />

The Euro-Arab Dialogue 232<br />

The Supply Recovers 236<br />

‘Sweating it out’ 237<br />

The Special General Assembly 241<br />

Saudi Arabia Stands Firm 245<br />

To the End 248<br />

The Energy Co-ordination Group 249<br />

Conclusion 251<br />

Conclusion 255<br />

Notes 265<br />

Archival Records 297<br />

List of Acronyms and Terms 301<br />

Bibliography 304<br />

Index of Names 313<br />

Index of Subjects 316<br />

7

Foreword<br />

October 2003 marked the 30 th anniversary of the Arab oil embargo levied<br />

against The Netherlands as a ‘punishment’ for its pro-Israeli stance in the<br />

October War. On October 6, 1973, Egyptian and Syrian troops attacked<br />

Israel in an attempt to regain the land occupied by Israel since 1967, and<br />

for several days the Israeli army had its back against the wall. In The<br />

Netherlands, the first reports of the war aroused great concern: Israel<br />

must be helped as in 1956 and in 1967.<br />

The Dutch government led by Prime Minister Joop den Uyl had been in<br />

power in The Netherlands since May 1973, a coalition consisting of, on<br />

the one hand, three progressive parties, the Dutch Labour Party (Partij<br />

van de Arbeid, PvdA) and two smaller parties: the progressive-liberal<br />

d’66 and the Radical Party (ppr), and on the other hand, the Catholic<br />

People’s Party (the Katholieke Volkspartij, kvp) and the protestant Anti-<br />

Revolutionary Party (arp). After the outbreak of the October War, the<br />

Den Uyl Cabinet left no doubt as to its pro-Israeli sympathies, making it<br />

clear in a governmental statement that it held Egypt and Syria responsible<br />

for initiating hostilities and for unilaterally violating the truce. In the European<br />

Community, too, The Netherlands took a more emphatically pro-<br />

Israeli stand than did other member states, so much so that for a while<br />

The Hague found itself isolated.<br />

Nor was this merely a matter of words. Under conditions of strict secrecy,<br />

a considerable quantity of ammunitions and spare parts was sent<br />

to Israel, an extensive military operation in Dutch terms, which it has<br />

long been maintained was undertaken without the knowledge of the Cabinet.<br />

This political and military support for Israel would subsequently be<br />

given as the reason for an oil embargo levied against The Netherlands.<br />

Yamani, the Saudi Minister responsible for oil matters, himself declared<br />

that this was the main motive for the embargo.<br />

9

Yet the affair of the oil embargo was by no means merely a response<br />

to the help lent to Israel. The oil crisis was also part of, or rather an expression<br />

of, an intense power struggle in the international oil sector. The<br />

radical Arab oil producers were intent on breaking down the traditional<br />

relations in this sector in which The Netherlands occupied an important<br />

position. It was the homeport of Shell, one of the largest of the oil multinationals.<br />

Furthermore, Rotterdam was a crucial switch-point in the<br />

whole circuit of the processing and distribution of oil in Western Europe.<br />

An embargo against The Netherlands seemed to affect half of North-West<br />

Europe.<br />

In various respects, the oil crisis was a first test case for the Den Uyl<br />

Cabinet, for it presented enormous problems, not only of foreign policy<br />

but also with regard to domestic and socio-economic affairs. In the arena<br />

of international politics, the oil crisis demanded that fundamental choices<br />

be made concerning relations between North and South, the American-European<br />

relationship and relations within the European Community.<br />

The oil crisis had a huge influence on Dutch domestic politics. The<br />

Central Planning Bureau predicted a marked rise in unemployment,<br />

slackening economic growth, increased inflation and possibly great damage<br />

to the port of Rotterdam and Dutch business life. For on paper, as one<br />

newspaper wrote a few days after the announcement of the embargo,<br />

turning off the oil tap was nothing short of a national disaster. The Dutch<br />

public was confronted with the prospect of Sundays without cars, of<br />

petrol rationing and restrictions on the use of electricity.<br />

What above all prompted us to write this book was the fascinating and<br />

at the same time complex totality of the oil crisis. In addition to which,<br />

this crisis suddenly placed The Netherlands centre stage in the theatre of<br />

international politics. The oil embargo focused all eyes on The Hague. So<br />

far, relatively little has been written on the role of The Netherlands during<br />

the oil crisis. Several studies have appeared, but an extensive study covering<br />

the whole range of different aspects has been lacking. More curious is<br />

the fact that no one has hitherto undertaken a thorough investigation of<br />

the archives of those ministries most involved in the oil crisis.<br />

Thanks to the Dutch Freedom of Information Act, we were allowed<br />

ample access to the most restricted records that had a bearing on the crisis;<br />

which is to say that those ministries closely involved in the crisis – Foreign<br />

Affairs and Economic Affairs – made their records freely available.<br />

Abroad too, specifically in the United States, we were granted access to<br />

relevant archival documents, often for the first time.<br />

10

Naturally, a number of questions remain unanswered. On certain<br />

points the archives contain no information, such as, in the matter of<br />

secret weapons deliveries to Israel. Nor were interviews always capable of<br />

filling these lacunae. Furthermore, the oil companies involved declined to<br />

allow us access to their company archives, because of which, in part, we<br />

have had to set ourselves several limits and have deliberately left (indeed,<br />

have had to leave) some aspects unconsidered.<br />

In addition, we pay scant attention to the financial-monetary aspects<br />

of the Dutch position or to the long-term consequences for the Dutch<br />

economy. Nevertheless, this study does, in our view, embrace several new<br />

points of view on Dutch foreign policy and, not least, on the policy of the<br />

Den Uyl Cabinet.<br />

In the end, we decided to write a case study focusing mainly on the political<br />

actions of the government, concentrating mainly on those ministers<br />

and ministries most significantly involved. The construction of the<br />

book is such that we try in each chapter to deal with a particular aspect of<br />

the oil crisis: Dutch Middle East politics, Dutch European politics, domestic<br />

measures, and so on.<br />

We are most grateful to the following (archive) assistants and civil servants<br />

who provided help: Francien van Anrooy and Sierk Plantinga of<br />

The National Archives; Fred van den Kieboom and Radjen Gangapersadsing<br />

at the Cabinet Office; Hans den Hollander, Henja Korsten, Peter<br />

van Velzen, Marco Verhaar and Ton van Zeeland at the Foreign Ministry;<br />

Sam Martijn of the Central Archives Depot at the Ministry of Defence;<br />

Th.J.N. Knops, Henrietta Kruse and J. Zuurmond at the Ministry for<br />

Economic Affairs; Ella Molenaar, Monique van der Pal, Cees Smit,<br />

Willeke Tijssen and Mieke IJzermans of the International Institute for<br />

Social History and Jaap van Doorn and Maarten van Rijn at the Ministry<br />

of Justice.<br />

We would also like to thank those individuals involved at different<br />

stages who have been prepared to read (parts of) the manuscript and offer<br />

constructive criticism. These were: F.E. Kruimink (then Co-ordinator of<br />

the Dutch Intelligence and Security Services), J.P. Pronk (Minister of<br />

Development Cooperation), A. Stemerdink (Under-Secretary of Defence),<br />

M. van der Stoel (Minister of Foreign Affairs), H. Vredeling (Minister<br />

of Defence), W.Q.J. Willemsen (Secretary of the Co-ordination<br />

Group for Oil Crisis Management and of the Ministerial Commission on<br />

the Oil Crisis) and G.A. Wagner (Chief executive of the Royal/Shell<br />

Group). We also wish to thank Paul Aarts (University of Amsterdam) for<br />

11

his advice; and to extend thanks to all those who were ready to give us<br />

their time in interviews or to provide written answers to our questions. Of<br />

course, we as authors take full responsibility for the final text of this<br />

book.<br />

Amsterdam, September 2004<br />

Duco Hellema, Cees Wiebes and Toby Witte<br />

12

1<br />

War in the Middle East<br />

On 6 Ocober 1973, large numbers of Egyptian and Syrian military units<br />

crossed the frontiers with Israel that had held since 1970. Around 240<br />

Egyptian warplanes crossed radar installations. At the same time, some<br />

1800 artillery and mortar positions opened up along the whole front and<br />

700 Syrian tanks attacked the Golan Heights where the Israeli land forces<br />

had only been able to deploy some 150 tanks. Although reports had already<br />

been circulating throughout the summer of an Egyptian-Syrian attack,<br />

the Israeli army command appeared to be caught by surprise. It<br />

seems that they were only convinced that the threat was serious a few days<br />

before the actual outbreak of the war. The possibility of a pre-emptive<br />

strike was briefly considered, but there was insufficient time for the necessary<br />

preparations. And furthermore, Israel would then be branded in international<br />

opinion as the aggressor. The decision therefore, as the Dutch<br />

Ambassador G.J. Jongejans reported to The Hague, was to wait whilst at<br />

the same time ‘seeking the full moral and political advantage’ of that restraint.<br />

1<br />

The question is whether the aggressors really had set themselves the<br />

aim of ‘wiping Israel from the map’. Possibly their intention was merely<br />

to realise limited military objectives and to cause an international crisis<br />

which would make the Great Powers realise that continued political impasse<br />

was unsustainable. Whatever the case, the Arab advance was an<br />

impressive success, and the Israeli military situation rapidly became serious.<br />

Within a very short time, the Egyptian forces had crossed the Suez<br />

Canal and broken through the Israeli line of defence. The Egyptian Army<br />

was able to re-take most of the Suez East Bank, occupied by Israel ever<br />

since the 1967 war, while at the same time the Syrian army succeeded in<br />

occupying a large part of the strategically important Golan Heights. It<br />

seemed that a real disaster for Israel was taking shape.<br />

13

After about four days, however, events began to turn. Israel managed<br />

to halt the offensive and began its own counter-attack. Israeli forces managed<br />

to regroup on the Golan, and on October 10, tank units broke<br />

through the Syrian defences, bringing Damascus within range of Israel’s<br />

artillery. Tel Aviv decided, however, not to pursue this course, since the<br />

Soviet Union had made it clear that any attack on Damascus would not be<br />

tolerated. In addition, further advance would be likely to incur unacceptable<br />

losses and would also run the risk that Jordan might become more actively<br />

involved. In the Sinai, the Egyptian army was managing for the time<br />

being to stand its ground, but during the night of October 15, Israeli tank<br />

units crossed the Suez Canal with the aim of isolating the Egyptian 3 rd<br />

army. The plan worked, and on October 21 this army corps was almost<br />

completely cut off from the outside world. 2<br />

On October 16,whenitbecameapparentthat Egypt and Syria were in<br />

deep trouble, Soviet premier Alexei N.KosyginflewtoCairotourgethe<br />

Egyptian president Anwar Sadat to call acease-fire.HeshowedSadat<br />

satellite photos of the Israeli advance, and on October 18,whentheIsraeli<br />

army had established a bridgehead on the western bank of the Suez Canal,<br />

Sadat agreed. Leonid Brezhnev, the Soviet leader, informed Kissinger and<br />

Nixon (who were at the time totally preoccupied by the Watergate affair)<br />

of Sadat’s willingness, and because Washington did not immediately respond,<br />

Brezhnev invited Kissinger to Moscow for further talks. This delay<br />

allowed Israel time to advance further against Egypt. 3<br />

On October 22, the Security Council adopted a resolution calling for a<br />

cease-fire. Although the two sides accepted this resolution, the fighting in<br />

fact continued. In the night of October 24– 25, the Security Council again<br />

called for a cease-fire and further demanded that the belligerent parties<br />

withdraw to the positions held on 22 October. International tension increased.<br />

The Soviet Union threatened direct military intervention if the<br />

Israeli advance were not halted. Washington reacted on October 25 by<br />

putting into operation Defense Condition 3 (DEFCON III) which meant<br />

that the American armed forces were put on a higher alert, including the<br />

announcement of a nuclear alert. 4 To the annoyance of West European<br />

countries, this also involved the American troops in Europe, even though<br />

there had been no discussion of this within nato. Emotions were quickly<br />

calmed, however, when Washington withdrew DEFCON III on October<br />

26. One day later, the first meeting took place between Israeli and Egyptian<br />

officers. Three days later an agreement was reached on the exchange<br />

of prisoners of war. 5<br />

The October war was not the first confrontation between Israel and its<br />

14

neighbouring Arab states. There had been wars in 1948, 1956 and again<br />

in 1967, all of them decided in Israel’s favour. In the Six-Day War, in particular,<br />

Israel had succeeded in considerably expanding its territory, taking<br />

in the Sinai desert (which led to the closure of the Suez Canal), the<br />

Gaza strip, the Golan Heights, and the West Bank of the Jordan. The end<br />

of the war initiated a period of protracted and fruitless diplomatic manoeuvrings<br />

in search of a peace accord, the starting point for which<br />

would necessarily have to be an end to this Israeli territorial expansion.<br />

To this end, on 22 November 1967, the Security Council adopted resolution<br />

242, a resolution which in subsequent years was to give rise regularly<br />

to diplomatic differences of interpretation, even within the ec. While the<br />

English version called for ‘withdrawal of Israel’s armed forces from territories<br />

occupied in the recent conflict’ the French version demanded that<br />

Israel withdraw from the territories occupied (‘retrait des forces armées<br />

israeliennes des terrritoires occupés’).<br />

The failure to find a political solution to the Middle East conflict ensured<br />

continuous tension in the area from 1967 to 1973, with the differences<br />

between the Soviet Union and the United States playing an increasingly<br />

important role. Time and again, hostilities flared between Israel and<br />

an Egypt enjoying large-scale military and economic support from<br />

Moscow. In the summer of 1970, after long and delicate negotiations, a<br />

cease-fire was agreed, but it proved impossible to reach agreement over a<br />

peace accord. In the Arab world, this impasse served to increase frustration.<br />

In January 1973, Sadat warned that a new war was beginning to<br />

look inevitable unless a political solution could be found soon. On October<br />

6, he was vindicated.<br />

The outbreak of the October War brought the two Great Powers, the<br />

Soviet Union and the United States, unexpectedly and sharply into conflict.<br />

From the early 1970s on, relations had improved between the Soviet<br />

Union and the usa. In May 1972, Brezhnev and Nixon had met in<br />

Moscow and jointly signed the salt-i treaty. In the meantime, the Conference<br />

over Security and Cooperation in Europe (csce) had been set up.<br />

It seemed that a new period of détente had begun.<br />

Egyptian and Syrian dissatisfaction with the situation in the Middle<br />

East was well-known. Rumours had circulated earlier of a possible<br />

Egyptian-Syrian attack on Israel, and in January the joint armed forces of<br />

Egypt, Syria and Jordan were put under the command of the Egyptian<br />

Minister for War. Nonetheless, most informed opinion held that the three<br />

nations possessed insufficient military resources to see such a venture<br />

through successfully. 6 15

Early in 1973, Moscow decided to supply Egypt with extra military<br />

material whilst at the same time, in Cairo, continuing to press for a diplomatic<br />

solution. Moscow’s strategy failed, for on October 4 the Soviet<br />

leaders were informed of Egypt’s intention to attack Israel within a few<br />

days. Immediately, the Kremlin sent transport planes to both Cairo and<br />

Damascus to collect the families of advisors and diplomats. Washington,<br />

however, remained convinced that Sadat would not start a war. 7 Once<br />

war had broken out, both Washington and Moscow immediately set up<br />

an airlift. The Soviet airlift came into operation the third day of the war,<br />

in spite of the fact that the Soviet military leadership expected Arab successes<br />

to be of only a temporary nature. On October 9, the airlift was concentrated<br />

solely on Syria, since the Syrian military situation was rapidly<br />

deteriorating. Supplies were still modest: no tanks or aircraft, only fuel<br />

and ammunition; but on October 10, Antonov-12 and the gigantic<br />

Antonov-22 transport planes began flights to Egypt. 8<br />

On October 14, several days after the Soviets began provisioning and<br />

after a week of hesitancy and differences of opinion, the usa announced<br />

that it was beginning delivery of weapons to Israel. The American airlift<br />

ran via the Azores. In all probability, however, the Americans began supplying<br />

Israel earlier, albeit on a limited scale. For example, as soon as the<br />

war broke out, American supplies were redirected from West Germany.<br />

The major West European countries were reticent in their response to<br />

the Middle Eastern war. Both French and British governments called for<br />

an arms embargo and refused to provide the belligerent parties with materials,<br />

an attitude which rapidly assumed an anti-Israeli complexion, at<br />

least partly as a result of statements from both countries over who was to<br />

blame. In addition to which, France continued to supply other Arabic<br />

countries, for example Libya, without specifying that such supplies<br />

should not find their way to Egypt or Syria. 9 West Germany adopted a<br />

much less outspoken approach. Bonn declared that it was not wholly in<br />

sympathy with Israel, but turned a blind eye to the movement of American<br />

supplies to Israel from West German soil. Within the European Community,<br />

not only did a majority seem disinclined to come out openly or<br />

actively in support of Israel, there was also unease over the role played by<br />

the Americans in the war and over the lack of consultation, particularly<br />

when Nixon put American troops on a high alert. In this regard, however,<br />

The Netherlands was the exception.<br />

16

The Netherlands and the Middle East<br />

As during the 1967 war, the first reports of the war in the Middle East<br />

caused great concern in The Netherlands. In its assessment of developments<br />

in the Middle East, The Netherlands had firmly allied itself with Israel<br />

over two decades. Originally, the Dutch had vacillated for some time<br />

before recognising the Jewish state, careful lest Islamic Arab countries<br />

should be antagonised in view of the problems with Indonesia. 10 But during<br />

the 1950s and 1960s, a ‘special alliance’ developed between the two<br />

countries. During the wars of 1956 and 1967, the Netherlands supplied<br />

Israel with military materials, though it should be added that policy in<br />

1956 was heavily influenced by the desire to see Nasser’s Egypt brought<br />

to heel. 11 The government also tried to offer Israel diplomatic support on<br />

various other occasions, in particular in the 1960s over the question of<br />

the Israeli-occupied territories.<br />

In the diplomatic battles over the question of whether Israel should return<br />

all of the occupied territories to the surrounding Arab nations, The<br />

Netherlands always interpreted resolution 242 in such a way that the possibility<br />

of strategic ‘border corrections’ would remain open. It was frequently<br />

emphasised in The Hague that Israel had the right to secure borders.<br />

On the Palestinian question, too, The Hague came out in support of<br />

Israel: the position and status of the Palestinians were a humanitarian and<br />

not a political issue. In the General Assembly of the un, The Netherlands<br />

voted against resolutions calling for the Palestinian people’s right to selfdetermination.<br />

The period in office of the Foreign Minister, W.K.N. Schmelzer (1971-<br />

1973), saw a cautious change of political direction. In the General Assembly<br />

in December 1972, The Netherlands backed the famous resolution<br />

2949 which recognised the rights of the Palestinians as an inseparable<br />

part of the peace process, in spite of both Israeli and American dissent.<br />

In the same year, Schmelzer declared that border corrections were only<br />

possible if all parties accepted them. Inevitably, such views introduced an<br />

element of estrangement into Dutch-Israeli relations. 12 These developments<br />

were accompanied by a closer rapprochement with the Arab countries,<br />

a process already begun in the late 1960s.<br />

During this period, although it became increasingly more difficult for<br />

the Foreign Ministry to consent to arms deliveries to Israel, 13 Dutch-Israeli<br />

military contacts were never completely broken. Israeli soldiers, for<br />

example, trained in The Netherlands in 1971 and 1972. Military instructors<br />

familiarised their Israeli colleagues with the lightly armoured person-<br />

17

nel carriers, the m-113’s; Israelis learned to shoot, drive, manoeuvre and<br />

navigate the m-113’s, and for this purpose they received secret training at<br />

the Royal Engineers Training School for Navigation and Diving. An exercise<br />

involving crossing the Maas with an m-113 was held near Zaltbommel.<br />

14 The m-113’s were to be used in crossing the Suez Canal in October<br />

1973. According to the Military Intelligence Service (mid) documents,<br />

the Israelis conducted their exercises in The Netherlands because ‘in the<br />

circumstances instruction from the American side would have been too<br />

sensitive’. 15<br />

Shortly before the October War, The Netherlands and Israel were still<br />

cooperating in the modernisation of the cannons of Israel’s Centurion<br />

tanks. A number of Israeli military personnel were given training at the<br />

Army tank workshops in Amersfoort. Parts for Centurions were also<br />

flown to Israel from the Soesterberg military airfield, 16 a rather remarkable<br />

transaction since the new (PvdA) Minister, M. van der Stoel, had decided<br />

on August 30 that all military deliveries to states immediately involved<br />

in the Israeli-Arab conflict must cease. 17<br />

Support for Israel<br />

On October 6, at the request of the Israeli Foreign Ministry, the Dutch<br />

Ambassador in Jerusalem sent a communication to The Hague that there<br />

were ‘massive concentrations of Egyptian and Syrian armed forces in attack<br />

positions’ gathered on Israel’s borders. From New York it was also<br />

reported that un observers were seeing ‘strong indications’ that Syria and<br />

Egypt wanted to embark on acts of war. It was assumed in New York that<br />

the intention was probably to achieve limited military objectives in order<br />

to be able subsequently to exploit the political situation. The Ambassador<br />

in Jerusalem was of the same view, maintaining this assumption<br />

even after the outbreak of the war. It was further assumed that Israel<br />

would rapidly push back the invaders through its supremacy in the air, an<br />

assessment that soon proved overly optimistic. 18<br />

In spite of the political shifts of the preceding years, The Netherlands<br />

came out 100% behind the Israeli cause. At first, The Hague – including<br />

the Dutch Foreign Ministry – was uncertain of the situation in the Middle<br />

East. On Sunday, October 7, Van der Stoel in fact was not prepared to<br />

comment. In the meantime, it was clear that Egypt wanted to petition the<br />

General Assembly and did not want the Security Council to intervene.<br />

Van der Stoel’s preference, on the contrary, was for the Security Council<br />

18

to be brought in. The Permanent Representative in New York, R. Fack,<br />

was nevertheless instructed not to oppose a debate on the Middle East in<br />

the General Assembly. 19<br />

On October 8, a high-level discussion of the conflict took place at the<br />

Foreign Ministry between J.M. den Uyl, Justice Minister A.A.M. van<br />

Agt, Minister of Economic Affairs R.F.M. Lubbers, Van der Stoel and<br />

Defence Minister H. Vredeling. At that moment, Israel was in serious<br />

trouble. As reports of this meeting reveal, it was decided to call for a<br />

cease-fire as soon as possible on conditions acceptable to both sides,<br />

preferably on the basis of a restoration of the status quo ante. 20 The cooperation<br />

of the ec countries must be enlisted to prevent any Arab resolution<br />

which labelled Israel as the ‘aggressor’ being passed in the General<br />

Assembly. In any case, The Netherlands would vote against any such<br />

resolution, and would press for a quick meeting of the Security Council.<br />

In brief, it was decided during this consultation to lend all possible diplomatic<br />

support to Israel. 21<br />

In accordance with the conclusions of this consultation, the Permanent<br />

Representative at the un, R. Fack, was thoroughly briefed the same day.<br />

Above all, he was to oppose any resolution which condemned Israel as the<br />

aggressor. He was also instructed to vote against any resolution that demanded<br />

the implementation of resolution 242, since the situation was<br />

now very different following the breaching of existing borders. The Security<br />

Council was the appropriate organ for ending the conflict, to which<br />

end the first priority was suspension of the armed struggle, preferably on<br />

the basis of a restoration of the status quo ante. 22<br />

On Monday, October 8, the Dutch Foreign Ministry issued its first<br />

press statement on the war. According to this statement, it could be deduced<br />

from the reports of un observers that Egypt and Syria had initiated<br />

the open violence. The government hoped that the Security Council<br />

could find a formula acceptable to both parties that would lead to a<br />

cease-fire. 23 On the afternoon of October 8, thePermanentCommittee<br />

for Foreign Affairs met in emergency session. At the end of this consultation,<br />

it was given out to thepressthat all political parties, with the exception<br />

of the communist cpn and the pacifist psp, couldendorse the government’s<br />

position that restoration of the existing pre-war borders was<br />

essential. 24<br />

Meanwhile, under the instigation of the Second Chamber, a government<br />

statement was being prepared. This statement was worked out at<br />

the Foreign Ministry by the Department for International Organizations<br />

(dio), a branch of the Directorate-General for International Coopera-<br />

19

tion (dgis). This arose from the fact that, in the Netherlands at least,<br />

Middle Eastern policy had until that point always been a un affair. The<br />

Director-General for Political Affairs (dgpa), D.W. van Lynden, disagreed<br />

with what he considered an excessively pro-Israeli statement. 25<br />

This criticism of the policy pursued by the government, expressed by the<br />

dgpa, was to remain a significant factor throughout the entire period of<br />

crisis. Van Lynden, like a number of diplomats involved, continued to<br />

urge that this standpoint be modified to go some way to meet the Arab<br />

countries.<br />

On October 9, the government statement was made public. The Cabinet,<br />

it said, had noted with consternation the resumption of the acts of<br />

war initiated by Syria and Egypt, as was evident from the reports of un<br />

observers, among other sources. Egypt and Syria had thus unilaterally<br />

broken the truce that had held since 1970. The two assailants should<br />

therefore withdraw behind the armistice lines observed prior to October<br />

6. The government called on the Security Council to try to achieve a political<br />

solution based on Security Council Resolution 242.<br />

Through its choice of words, the Den Uyl Cabinet made it clear that it<br />

still stood firmly behind the interpretation of resolution 242 that the Arab<br />

countries considered pro-Israeli: Israel must withdraw from occupied areas<br />

(without the definite article). At the same time it was proposed that a<br />

political solution to the conflict had to be inseparably linked with a just<br />

and fair solution to the refugee question, meaning the question of the<br />

Palestinians. 26 What the declaration meant – as had been agreed in the<br />

ministerial discussions mentioned earlier – was support for Israel. In the<br />

event, the Dutch government statement was fairly generally supported in<br />

the Second Chamber, notwithstanding observations on the Palestinian<br />

question made by the PvdA and ppr. The PvdA leader, E. van Thijn, emphasised<br />

the need to strive for a solution to the Middle East conflict that<br />

would do justice to the political aspirations of the Palestinians. 27<br />

In New York, this government statement caused consternation among<br />

the Dutch Permanent Representation at the United Nations. Once Fack<br />

had scrutinised the statement he decided in consultation with his second<br />

man, subsequently Minister C. van der Klaauw, to give it as little publicity<br />

as possible. According to Fack, those in The Hague had been ‘unwise’<br />

since The Netherlands could not, after all, ‘maintain that a country trying<br />

to regain its own territory from a foreign occupier was committing<br />

aggression’. The position of conscientious balance and probity in the<br />

question of the Middle East, a position carefully constructed over past<br />

years, now threatened to collapse, Fack believed, like a house of cards. 28<br />

20

This was a first indication that his diplomats did not always subscribe to<br />

Van der Stoel’s viewpoint.<br />

But the government’s position could obviously be bent more towards<br />

the Arabs. On October 10, Van der Stoel had an interview with the Ambassadors<br />

of Saudi Arabia and Tunisia and with the Egyptian temporary<br />

chargé d’affairs concerning the Dutch position. It appears that at this<br />

meeting the Foreign Minister emphasised the fact that the government<br />

had called for a cease-fire based on a situation acceptable to both parties.<br />

It was not for The Netherlands, argued Van der Stoel, to say what the conditions<br />

should be before a cease-fire could be reached, although he stated<br />

his preference for a restoration of the truce boundaries of August 1970.<br />

The three Arab diplomats were evidently satisfied with this clarification.<br />

29 At that moment, it seemed that the two principles, ‘restoration of<br />

the status quo ante’ and ‘a cease-fire acceptable to both parties’, were<br />

evenly balanced. Two days later, however, during a European Political<br />

Cooperation consultation, the Dutch emphasis had shifted pre-eminently<br />

to the side of restoring the status quo ante.<br />

This did not prevent The Netherlands finding itself rapidly isolated<br />

within the ec. It was announced in the government statement that The<br />

Hague would make its attitude better understood within the consultative<br />

process with the nine member states. It was soon evident, however, that<br />

this was no easy matter, since most ec countries were not inclined to offer<br />

Israel their support. France and Italy, in particular, and to a lesser extent<br />

the uk, seemed rather to choose the Arab side. In the case of France, this<br />

became apparent during a sitting of the Security Council, when the<br />

French delegate pointed out that the current fighting was taking place in<br />

areas that had been occupied by Israel since 1967. France sought a peaceful<br />

solution to the conflict on the basis of resolution 242 (i.e. no restoration<br />

of the status quo ante) and expressed the desire that the entire Middle<br />

East problem should be involved in such a settlement. 30 It was evident in<br />

The Hague that French sympathies inclined to the side of the Arab countries.<br />

The Security Council appeared paralysed for the time being because<br />

the usa would not desert the Israelis, and furthermore neither Israel nor<br />

the Arab countries put much stock in any pronouncement from the Council.<br />

The conflict was to be decided on the battlefield.<br />

21

Military Support<br />

As we said earlier, the first reports arriving in The Hague, both from<br />

Jerusalem and New York, were still fairly optimistic over Israel’s military<br />

position. It was assumed that it was a limited military conflict in which Israel’s<br />

military superiority would ensure a swift Israeli victory. On Monday<br />

the 8th, Ambassador G.J. Jongejans reported from Jerusalem that the<br />

Israeli Cabinet had the previous day authorised crossing the existing truce<br />

boundaries. ‘As far as Israel was concerned, the war was actually already<br />

won.’ 31 But it turned out to be far from as easy as that.<br />

On October 7, the second day of the war, in a dramatic conversation<br />

the Israeli Ambassador to The Netherlands, C. Bar On, asked Minister<br />

Van der Stoel for military and material assistance. Undoubtedly, the Ambassador<br />

was fully aware that The Netherlands had assisted Israel with<br />

military material in the wars of 1956 and 1967. Bar On let it be known<br />

that Israel stood on the edge of the abyss and was desperately in need of<br />

ammunition and spare parts. The British and French governments had issued<br />

a ban on the export of arms to the warring parties as soon as the war<br />

broke out. American material support, to all appearances, was also very<br />

slow to get going during the first days of the war. Unlike Great Britain and<br />

France, the Dutch government did not ban the export of arms to the belligerents.<br />

According to the Ambassador, The Netherlands appeared to be<br />

the only remaining candidate for supplying Israel with the much-needed<br />

ammunition and spare parts. 32<br />

As Bar On recalls, Van der Stoel reacted rather coolly. Perhaps his caution<br />

was dictated by the initially optimistic reports from Jerusalem, but in<br />

any case he wanted to wait and see exactly how serious the Israeli situation<br />

was. Bar On remained in contact with Van der Stoel and with Premier<br />

Den Uyl and Vredeling, the Minister of Defence, throughout the following<br />

days. 33 The contacts with Vredeling were arranged by the PvdA<br />

Member of Parliament H. van den Bergh. Vredeling meanwhile had already<br />

intimated to him that he wished to send arms to Israel. 34<br />

As Minister of Defence, Vredeling played a central role in supplying<br />

arms to Israel. He has always stressed that his position was based on emotional,<br />

personal considerations. The events of the Second World War, the<br />

ex-resistance fighter later explained, must never be allowed to happen<br />

again. But despite all Vredeling’s noble-minded aims, the fact was that<br />

The Netherlands was being discretely pressured by the Americans.<br />

The background to this was that Foreign Minister Secretary Kissinger<br />

and Defence Minister James R. Schlesinger had clashed over extra arms<br />

22

deliveries to Israel. The initial American reaction was one of reservation,<br />

but apparently this caused considerable unrest in some quarters in Washington,<br />

given Israel’s initially threatened military situation. On Sunday<br />

morning, the cia operator at the American embassy in The Hague in<br />

charge of communications with headquarters in Langley, Virginia, received<br />

a critic from cia headquarters. Such a coded telegram requires a<br />

response within a few hours. He therefore contacted the cia Chief of Station<br />

in The Netherlands, Carlton B. Swift Jr., who had arrived in The<br />

Hague in the summer of 1973. 35<br />

Swift was instructed to approach the Dutch Cabinet to supply Israel<br />

with as many weapons and spares as possible. The critic emphasised that<br />

the political heads of the American Embassy had not been informed of<br />

these instructions. The critic that Swift received contained this brief request<br />

to the Cabinet to satisfy the Israeli requirements to whatever extent<br />

possible. 36 Swift carried out his brief in discrete fashion. On Sunday<br />

morning he contacted the Head of the Dutch Internal Security Service<br />

(the bvd), D. Kuipers, and the Intelligence and Security Co-ordinator of<br />

the Ministry of General Affairs, (the Prime Minister’s Office) F.E.<br />

Kruimink, who later confirmed that he and Kuipers were unexpectedly<br />

called at home by Swift on Sunday, October 7, to discuss a matter of great<br />

urgency. 37 Swift’s request found a receptive audience. Kruimink was to<br />

play an active role in the deliveries of arms. 38<br />

As we said earlier, a meeting on Monday, October 8, of the five Cabinet<br />

members most involved led to the conclusion that The Netherlands<br />

should support Israel. Both Van der Stoel and Vredeling deny that military<br />

support was discussed at this meeting. 39 Nonetheless, a remarkable<br />

incident occurred that same day. As the newspaper De Telegraaf reported,<br />

‘two days after the outbreak of the war’, two Israeli transport planes<br />

arrived at Gilze Rijen airport. A note in the Den Uyl archive, written by<br />

Den Uyl himself, reads: ‘Two days after the outbreak of the war in the<br />

Middle East, the Cabinet allowed several Israeli transport planes that had<br />

come to The Netherlands to fetch armaments to return empty-handed’. 40<br />

The journalist F. Peeters, who has written a book on the Dutch-Israeli<br />

military alliance, believes that the two aircraft actually left loaded. 41 Under-secretary<br />

for Defence Stemerdink confirmed that the two aircraft had<br />

indeed been loaded with American communication and detection equipment<br />

sent from West Germany. In all probability there were no Dutch<br />

materials sent; there had been at that stage inadequate preparation on the<br />

part of the Dutch. 42 In Vredeling’s view, there had been no political permission<br />

for this procedure, and in any case he himself was not fully in-<br />

23

formed. 43 Stemerdink, however, was of the opinion that no Dutch permission<br />

was necessary, since it was a matter of American transport of materials,<br />

as had often occurred before. The Dutch government had nothing<br />

to do with it. 44 Stemerdink takes a rather laconic line here, since the aircraft<br />

that collected the American materials were from Israel, a country at<br />

war. In this connection, it is even more remarkable that Den Uyl noted<br />

that the government had allowed these Israeli transport planes to return<br />

empty. This note from the Den Uyl archive may well indicate that the premier<br />

clearly knew what was going on.<br />

Meanwhile, Ambassador Bar On had convinced Vredeling, Van der<br />

Stoel as well as Den Uyl of Israel’s great need of ammunition. This request<br />

set a series of activities in motion. Vredeling asked the Secretary-General<br />

of Defence, G.H.J. Peijnenburg, to obtain information from the Israeli<br />

military mission in Paris regarding Israeli wishes. It was in the meantime<br />

known that there was a special need for 105 and 155 mm artillery. It was<br />

not only Vredeling who was trying to clarify the situation. Van der Stoel<br />

instructed his Ambassador in Washington, R.B. van Lynden, to find out<br />

what the us Government thought The Netherlands’ contribution should<br />

be. And Den Uyl requested Kruimink to draw up a memorandum over<br />

arms deliveries. 45<br />

The information requested by the Ministers was presented the following<br />

day. Vredeling received a memorandum from Peijnenburg, whose information<br />

had been obtained by the Quartermaster General, J.L. Antonissen,<br />

who in turn had been instructed by the Israeli military attaché in<br />

Paris. The Israeli reply was clear: Israel needed as much as possible 105<br />

and 155 mm ammunition of any type, both for cannons and howitzers.<br />

Antonissen informed Peijnenburg that The Netherlands had no surplus<br />

stocks of this ammunition, i.e. stocks beyond those needed for exercises<br />

and in case of war. Stocks of 105 mm in particular were still being built<br />

up. 46<br />

According to Peijnenburg, The Netherlands could nevertheless relinquish<br />

munitions and reorder replacements from Eurometaal (the former<br />

Artillery Establishment). Delivery of 155 mm shells was easier than the<br />

105 mm ammunition, because the English would be able to cite licence<br />

restrictions as an objection to their being re-exported to Israel. Antonissen<br />

thought this unlikely, however. Peijnenburg, concluding his advice,<br />

stressed that the Cabinet, or a few Ministers, must now decide whether<br />

deliveries to Israel should be permitted to go ahead. He pointed out that in<br />

1967 deliveries had been made out of Dutch stocks and that this had been<br />

successfully carried out without publicity. Peijnenburg had meanwhile let<br />

24

Bar On know by telephone that the Israeli military attaché in Paris had<br />

been contacted to establish exactly what Israel’s needs were, and that<br />

once this was known, the decision lay with the Cabinet. Bar On was told<br />

no more than this by him. 47<br />

More information arrived at the Ministry for Foreign Affairs on October<br />

9.FromWashington came the news that The Netherlands must see<br />

what they themselves could do, 48 which meant that in any case there<br />

would be no Americanrepudiation.VanderStoelwaskeptinformedof<br />

activities at the Defence Ministry. A Foreign Ministry memo of October<br />

9 reported the Israeli request for ‘any type and any quantity’ of 105 and<br />

155 mm ammunition. Defence had let it be known that smaller quantities<br />

of the above calibre were availablefromsurplus stock and could in<br />

addition be supplied from stocks intended for theDutcharmy’sown<br />

use. 49<br />

The following morning, October 10, DenUylreceived a note from<br />

Kruimink titled: ‘Several factors of relevance in evaluating the question:<br />

what is the value of 11,000 tank shells for Centurion tanks.’ The note<br />

made reference to the possible delivery of 11,000 tank shells, field telephone<br />

cable, tank parts and also mines. The artillery ammunition that<br />

had been so centrally significant in the Defence papers was not even mentioned<br />

in Kruimink’s note. According to him, what was important at that<br />

time was above all spare parts and tank shells for the Israeli Centurions.<br />

50 This shift was probably linked with developments in the war, for<br />

after the first few difficult days, the Israeli army had now gone on the offensive.<br />

The Israeli interest in ammunition and spares for Centurion tanks was<br />

understandable. These tanks constituted about half the Israeli tank force,<br />

in a situation in which they were confronted on both fronts with superior<br />

numbers of Syrian and Egyptian tanks. 51 The British Centurion tank was<br />

also the standard tank in both Dutch and British armies. The British government,<br />

however, as already mentioned, had banned the export of<br />

weapons to both belligerent parties. 52 For the Dutch army, the 11,000<br />

tank shells constituted ‘ammunition for the first phase’, predestined for<br />

five days of Dutch fighting in the event of war (mainly in Germany, it was<br />

hoped), whereas this was probably sufficient to see the Israelis through<br />

three days of battle.<br />

Given the content of his note, Kruimink was assuming a secret operation.<br />

He indicates briefly how transport to Israel could be worked out<br />

practically and also made suggestions for camouflaging the necessary replenishment<br />

of stocks in The Netherlands, which would have to occur in<br />

25

consultation with Britain. It was therefore inevitable, thought Kruimink,<br />

that Britain would have to be approached over this matter of re-stocking.<br />

Contact would also have to be made with the Americans. 53<br />

The problems were resolved on Wednesday morning, October 10, in a<br />

conference at the Dutch Foreign Ministry involving Den Uyl, Van der<br />

Stoel, Vredeling and the Director-General of Political Affairs, Van Lynden.<br />

54 The position of the Foreign Affairs chiefs was immediately clear,<br />

both the Head of the Department for Africa and the Middle East (dam)<br />

and Van Lynden opposed it. The head of dam argued: ‘Unless M (the<br />

Minister) definitively decides that under the present battle circumstances<br />

Israel is to be supplied with military materials, I would ask you to consider<br />

whether in this conflict situation any material should be supplied to any<br />

warring party that might contribute to the continuation of war.’ Van Lynden<br />

also advised against supplying Israel unless Israel’s own territory was<br />

under threat. In the course of these deliberations, Van Lynden referred the<br />

three Ministers to existing policy: ‘not to supply the belligerent parties’<br />

and ‘not to supply Israel or the Arab states since the forming of the new<br />

Cabinet’. Further, Van Lynden stressed the danger of reprisals by the<br />

Arab countries when it came to oil. 55<br />

Finally, the three Ministers involved decided to withhold supplies ‘provisionally’.<br />

At least, that is what was noted on the Foreign Ministry memorandum.<br />

56 It was certainly not a definitive refusal; quite the contrary, it<br />

was a decision which, in view of the attitude and choice of words of those<br />

involved, still left everything open. Vredeling, according to what he himself<br />

said, found the decision taken wholly unsatisfactory. 57 But Van der<br />

Stoel’s subsequent account also leaves considerable room for interpretation.<br />

At the time, Dutch supplies seemed to Van der Stoel ‘personally’ unnecessary<br />

because American assistance with weaponry was already under<br />

consideration. Furthermore, as he explained some 25 years later, the<br />

ex-minister ‘made a possible exception for American armed materials<br />

that had been given us on loan’. 58 This is a remarkable addition, since the<br />

urgent Israeli interest in Centurion spare parts did in fact concern material<br />

that The Netherlands had been ‘loaned’ by the usa in the mid-1950s, at<br />

the time of American military assistance under the Mutual Defense Assistance<br />

Program (MDAP). Supplying Israel with Centurion parts and ammunition<br />

therefore, at least in part, did involve material given by the usa<br />

‘on loan’.<br />

Van der Stoel also remembered that there had been talk of a swap, i.e.<br />

deliveries in exchange for later compensation. 59 In all probability this<br />

mooted exchange concerned the Centurion shells to be supplied. The fact<br />

26

is that stocks lay ready in Great Britain, destined for Israel, already paid<br />

for, but which because of the British arms embargo could not be delivered.<br />

The solution was simple: The Netherlands would supply Israel and<br />

would later get back these materials from the stocks lying ready in Great<br />

Britain. In this way, the problem raised by Kruimink could be solved,<br />

namely, how to restore stocks to the same level without drawing attention<br />

to oneself. Through such a swap, the relevant British military authorities<br />

need never be informed of the Dutch deliveries. There is another reason<br />

for assuming that the decision-making of October 10 went further than a<br />

simple ‘provisionally not’. Den Uyl later remembered, without actually<br />

giving the date as October 10, that it was agreed it would be ‘a good idea<br />

to transport reserve ammunition from Volkel’. As he added to the Dutch<br />

historian Grünfeld, ‘in fact it never came to that’. 60 But this added remark<br />

is not correct: it most certainly did come to that.<br />

In view of the content of Kruimink’s note and the debates about an exchange,<br />

the indicators all suggest a secret operation. The decision ‘provisionally<br />

not to supply’ can also be interpreted as a decision for the time<br />

being to not officially supply, i.e. not according to all the stipulations in<br />

force. Subsequently, the Foreign Ministry would always deny that they<br />

had been involved in the surrender of arms export permits. However, an<br />

official procedure authorised by different departments was out of the<br />

question given the wording of Kruimink’s note and the decision-making<br />

of 10 October.<br />

Finally, a last point. There was a second important decision taken at<br />

that meeting. Both Van der Stoel and Den Uyl remembered that it was decided<br />

to offer the freedom of Dutch airfields for any possible American-Israeli<br />

airlift. Den Uyl later said that ‘from our side we then offered them<br />

the use of our airfields’. The airfield primarily in question was that of<br />

Soesterberg. In the end, the offer was not taken up because us transports<br />

were routed via the Azores. 61 However, there were Arab accusations that<br />

The Netherlands and Portugal were the only nato partners prepared to<br />

collaborate in setting up an American-Israeli airlift.<br />

Arms Deliveries<br />

Later on the same October 10, Vredeling informed Under-Secretary of<br />

Defence Bram Stemerdink that he had shared in the decision to supply Israel<br />

with weapons. He told Stemerdink that he had that morning thoroughly<br />

discussed the question with Van der Stoel and Den Uyl. 62 Vredel-<br />

27

ing and Stemerdink subsequently always maintained that they personally<br />

took this decision; that otherwise the whole process would have taken far<br />

too long, not least because of the anticipated opposition of Van der Stoel.<br />

But in the light of what we have already seen above, it is very much to the<br />

point to ask whether this picture is an entirely accurate one. Stemerdink<br />

has further since declared that ‘there was political consent to supply<br />

whatever was necessary’. 63<br />

Vredeling and Stemerdink came to the agreement that, if the whole<br />

matter were leaked, the latter would take responsibility and if worst came<br />

to worst he would resign to avoid bringing down the Den Uyl Cabinet in<br />

its infancy. They decided naturally to deny any knowledge of the operation.<br />

Next, Stemerdink contacted the Quartermaster General, Antonissen,<br />

who was to lead the whole operation. The Under-Secretary of Defence<br />

did not know that Antonissen had already been busy since Monday<br />

– or even Sunday – drawing up an inventory of what could be delivered to<br />

Israel. 64<br />

The question of arms deliveries preoccupied Van der Stoel, and in particular<br />

the ‘swap’ discussed on Wednesday morning. This is also rather<br />

remarkable in view of the fact that the Minister should not have been fully<br />

informed. Stemerdink recalled subsequently that he had a conversation<br />

with his fellow party member about this whole affair on Thursday, October<br />

11. Van der Stoel then returned to the question of whether The<br />

Netherlands would in fact be able to replenish stocks discretely after the<br />

war, Stemerdink setting out the reasons why this was not an insuperable<br />

problem. The stocks intended for Israel and now lying ready in Great<br />

Britain would after all be shipped to Rotterdam and with a little sleight of<br />

hand they could be unloaded. The ‘swap’ need never come to light. 65<br />

Dutch stocks would thus by the spring of 1974 be completely replenished.<br />

This happened with the assent of Stemerdink’s counterpart, the British<br />

Secretary for Defence; for by March 1974 the Labour Party had been returned<br />

to power in Britain, whereas a Conservative Defence Secretary<br />

would have undoubtedly declined to cooperate. 66<br />

Matters were efficiently expedited. According to Vredeling, the whole<br />

operation of 1973 was conducted on a need-to-know basis. At the ministry,<br />

Quartermaster General Antonissen, of course, knew about the<br />

whole operation, as did Brigadier General T. Meines, the logistics deputy<br />

working for the Quartermaster General. 67 Besides Antonissen, the<br />

Deputy Quartermaster General, General Major T.A. van Zanten, also<br />

knew about the operation. 68<br />

Meines confirmed that it was mainly tank parts and ammunition that<br />

28

were delivered to Israel, chiefly major components such as tank engines<br />

and various small spare parts for Centurions. Tank shells needed for the<br />

Israeli tanks were also sent. This material was fetched from the depots in<br />

Soesterberg and Utrecht and taken to Gilze Rijen. Material from Germany<br />

was also sent on. The ex-Israeli Ambassador Bar On has also said<br />

that it was mainly a matter of artillery ammunition, tank shells and spare<br />

parts. 69 Those directly involved later reported to Peeters that the tank<br />

shells were taken from the arsenals of the First Army Corps, and that the<br />

Centurion spare parts mainly consisted of shock-absorbers, gun turrets,<br />

caterpillar tracks, gearboxes and engines. But according to Peeters, that<br />

was not all. Machine guns and later parts for light amx-tanks were also<br />

flown to Israel, together with 0.40-canons, 22 mm ammunition for aircraft<br />

artillery and thousand-pound bombs. If it suited Israel better, these<br />

‘1,000 lbs’ were flown by the Dutch airforce, sometimes in f-27’s, to the<br />

American base Ramstein in Germany and there loaded into Israeli aircraft.<br />

70<br />

Meines points out that the Army was busy changing over to the West<br />

German Leopard tank. The Centurion material was thus becoming superfluous,<br />

and parts could readily be disposed of. The Centurions did not<br />

belong to the Dutch, they were on loan. This was also the case with the<br />

spare parts, although over time the Dutch army had also bought reserve<br />

parts themselves. 71 As far as the American-loaned material was concerned,<br />

Vredeling later emphasised that The Netherlands was not in a position<br />

to dispose freely of the relevant parts. Kruimink also accepts in retrospect<br />

that Antonissen maintained contact throughout the whole operation<br />

with a military attaché at the American embassy. 72 This was probably<br />

the mdap attaché or a functionary of the Military Assistance Advisory<br />

Group. We have already seen that there was no need to anticipate any<br />

problems from the Americans. Besides, Vredeling points out that the involvement<br />

of American Centurion material served a kind of ‘camouflage’<br />

function, for in case of discovery, it could always be maintained that the<br />

Centurions were being given back to the Americans.<br />

The material was transported to Israel in unmarked Israeli Boeing<br />

707’s from the Gilze Rijen military airfield, and according to Stemerdink<br />

also from Soesterberg, Ypenburg and Valkenburg. 73 These Boeings,<br />

which belonged to the Israeli airforce and the Israeli airline El Al, were<br />

sprayed grey to make identification more difficult. It is also possible that<br />

other 707’s were hired from European airline companies. Indeed, klm<br />

was very soon accused by the Arab side of being involved. The Israeli airforce<br />

itself commanded only seven Boeing 707’s.<br />

29

Each of the 707’s would have made an intermediate stop at the Belgian<br />

airfield Melsbroek. The transports took place at night, most probably<br />

commencing the night of October 12, and lasted several nights, possibly<br />

from October 12 to October 14, the day the American airlift openly went<br />

into operation. The military historian J. Schulten believes that the Israeli<br />

aircraft flew within nato airspace via civil flight corridors, giving<br />

Schiphol as their destination. The military personnel involved in the<br />

transport were mainly cadets of the Royal Military Academy in Breda,<br />

who were told that these were unexpected night-time exercises. 74<br />

It is not easy to establish just how important the Dutch deliveries were<br />

for Israel. Twenty years after the event, Vredeling gave his own view in a<br />

rather emotional fashion, piling on the agony and insisting on the significance<br />

of the supplies as though to justify his own actions. They were<br />

weapons, he said, that had been ‘begged and pleaded for’. It was a matter<br />

of sink or swim, and therefore, acting entirely in a personal capacity, he<br />

had decided to lend Israel a helping hand. 75 In Kruimink’s note, however,<br />

it had already been decided on October 10 that the weapons would arrive<br />

– and according to him did arrive – too late at the front to affect any ‘sink<br />

or swim’ situation. The Co-ordinator of the Intelligence and Security Services<br />

furthermore opined that Israel’s survival was no longer in question<br />

after the fourth day of the war. In view of this, he called the Dutch contribution<br />

‘valuable’, ‘more than a token gesture’, ‘but not decisive’. 76 Nevertheless,<br />

at the time, Kruimink found these comments no reason to speak<br />

out against the plans in his note. He pointed out that ‘if the Egyptians succeed<br />

in keeping parts of the Sinai’ the consequences would be seriously<br />

detrimental to Israel. 77 The Dutch transports thus may not have played so<br />

much an important role in defending the state of Israel against a threat to<br />

its survival, as Vredeling subsequently claimed, but they surely did help<br />

Israel in regaining the offensive. The Dutch government, or at least the<br />

ministers concerned, had already adopted the standpoint that a return to<br />

the status quo ante would be highly desirable for Israel, since it would allow<br />

Israel to enter peace negotiations from a position of strength. Albeit<br />

on a modest scale, through its supplies of military material The Netherlands<br />

contributed to the realisation of this goal while the war was still in<br />

progress.<br />

30

Foreign Ministry Denial<br />

In October 1973, Kruimink thought it would be impossible to keep the<br />

arms supplies a secret. The transport and loading would involve hundreds<br />

of military personnel. Peijnenburg was less pessimistic since previously,<br />

in 1967, the public had successfully been kept in the dark. And Peijnenburg<br />

was for a long time right. The arms deliveries of the October War did<br />

indeed escape public attention. When this became no longer feasible, first<br />

Stemerdink and subsequently Vredeling took personal responsibility.<br />

Den Uyl and Van der Stoel, let alone other members of the government,<br />

had known nothing.<br />

However, different individuals involved in the affair are of the opinion<br />

that it is highly unlikely that Den Uyl and Van der Stoel did not know.<br />

That, too, is the verdict of ex-Ambassador Bar On. He recalls that Van der<br />

Stoel was indeed initially unresponsive in his assessment. That was shortly<br />

after the outbreak of the war, but when the situation became more serious<br />

for Israel, the government – i.e. Den Uyl, Van der Stoel and Vredeling<br />

– decided to look at the Dutch position again. An actual airlift, they decided,<br />

was not possible. ‘But the Dutch government did agree to the possibility<br />

of Israel purchasing ammunition, particularly artillery ammunition<br />

and shells’. On his own admission, Bar On had constant contact over<br />

the affair with both Van der Stoel and Den Uyl as well as Vredeling. 78<br />

The Foreign Ministry and Van der Stoel furthermore played a remarkable<br />

role when psp member of the Second Chamber F. Van der Spek began<br />

to make trouble. On October 26, Van der Spek tabled written questions<br />

on the matter of arms deliveries. According to him, on October 12,<br />

13 and 14, unmarked b-747’s had landed at Schiphol to refuel and to<br />

transport weapons to the Middle East. Van der Spek wanted to know<br />

whether great risks had been taken. Was it likewise the case that on October<br />

19 military aircraft had landed on their way to the Middle East?<br />

This was close to the truth, and the answer to these parliamentary<br />

questions caused a number of problems. In a memo of November 2, Van<br />

der Stoel was informed that the draft reply should already by the beginning<br />

of the week, and with the utmost haste, be submitted to the Dutch<br />

Minister of Economic Affairs, Lubbers, and the Minister of Defence. But<br />

co-ordination led to considerable delay. Vredeling was meanwhile in<br />

agreement. In Economic Affairs and in Defence it was felt that, because<br />

of the political nature of the questions, Van de Stoel should be the first to<br />

sign it. The Minister was also informed that the Ministry of Economic<br />

Affairs wanted it borne in mind when framing the answer that ‘no li-<br />

31

cences for the export of arms had been issued’. Beside this, Defence had<br />

let it be known that the Gilze Rijen airfield had not been used as an intermediate<br />

stop for military aircraft on their way to the Middle East. 79<br />

In his reply to Van der Spek’s questions, Van der Stoel did not simply<br />

declare that no arms had been supplied to Israel. That would have been a<br />

lie. He answered, also on behalf of Lubbers and Vredeling, that since the<br />

outbreak of the war ‘no licences for arms exports to the Middle East had<br />

been issued’. That applied also to arms in transit. This was obviously a<br />

hypocritical answer: of course, no official export licence had been granted,<br />

since the entire operation was conducted in secrecy. The specific questions<br />

over Schiphol were answered with explicit denials. 80 The flights had<br />

in fact been from Gilze Rijen and possibly other airfields.<br />

Van der Stoel thought the formulation of the answers to Van der Spek’s<br />

questions, ‘no export licences’, was probably chosen ‘with reference to<br />

the loaned material made available by America’. 81 This is a remarkable<br />

comment, since the Dutch government had no authority to dispose of material<br />

given by the us on loan. 82 In retrospect, Van der Stoel also insisted<br />

on the formulation ‘to have been able to say in all conscience that no licence<br />

was given for the export of weapons during the Yom Kippur War’.<br />

Neither he nor Den Uyl had been informed of arms deliveries. 83 This is, in<br />

the strictest sense, true. Bar On stressed in this connection that there had<br />

been no question of delivering weapons, but the supply of ammunition<br />

and spare parts. 84 Others involved, both at the time and later, may well<br />

have relied on this tactical but dubious distinction, but if aircraft machine<br />

guns and mines were also supplied, the distinction is invalid.<br />

It is also not very plausible that Den Uyl was not immediately, or at least<br />

within a few days, fully informed. Den Uyl was certainly present at the discussions<br />

of October 10. Furthermore,hewouldinallprobabilityhave<br />

been informed of the transports soon enough byoneof the intelligence<br />

services. After all,itwasanoperationinwhich,quiteapartfromtheunrecognisable<br />

foreign aircraft, several hundred Dutch military personnel<br />

had been involved. Former member of parliament H. van den Bergh later<br />

brought to the world’s attention the story that in December 1973 Israeli<br />

Premier Golda Meir had effusively thanked Den Uyl at the Socialist International<br />

for his support, and that Den Uyl was highly surprised at this expression<br />

of gratitude. 85 But was Den Uyl surprised because he knew nothing<br />

about it (as Van den Bergh suggested) or because Meir thanked him so<br />

openly in the proximity of other witnesses? Brandt was also warmly<br />

thanked by Meir, but the reason for that show of gratitude was evident, for<br />

it was well-known that the American war materials had also been flown<br />

from West Germany.<br />

32

And indeed, Den Uyl need not have been so surprised. A week after the<br />

war broke out, the premier had received a cordial letter, dated October<br />

10, from the Israeli government warmly thanking him for the Dutch support<br />

that had been highly important to Israel. 86 Furthermore, it would be<br />

highly unlike Den Uyl to be left uncertain. Rumours were already circulating<br />

in October over Dutch arms deliveries. According to Vredeling,<br />

Den Uyl never once asked him what was going on, which in the light of<br />

Den Uyl’s curiosity, remarked on by Vredeling and others, could mean<br />

nothing other than that he was already fully informed. Bar On also claims<br />

that Den Uyl had been informed. 87 Ex-Minister of Economic Affairs Lubbers<br />

is of the opinion that Den Uyl had ‘some knowledge’ of the affair and<br />

that he suspected that Lubbers also knew. 88 Kruimink similarly thinks it<br />

highly improbable that Den Uyl knew nothing. 89<br />

These rumours were not only circulating in The Netherlands, but more<br />

significantly abroad. This was quickly evident from an undated memorandum<br />

to Van der Stoel, most probably written during the first days of<br />

the war. A report in the Dutch Foreign Ministry, most probably from a<br />

friendly intelligence service, reads: ‘The Israelis are anticipating some<br />

ammunition shortage for their artillery and have requested 105 and 155<br />

mm ammunition from The Netherlands, according to some Western Ambassador.’<br />

90 In Washington, various people were told both of the Dutch<br />

willingness to make an airfield available and of the arms deliveries. When<br />

Ambassador Van Lynden held a conversation with the Deputy Secretary<br />

of State, Kenneth Rush, on October 30, the latter expressed his appreciation<br />

of the Dutch role during the war. Rush stressed how disappointing<br />

the attitude of the other European partners and Spain had been. He admitted<br />

that the member states of Europe had not always been adequately<br />

consulted, but it was intolerable that they had denied Americans the right<br />

to use their airspace or the facilities to refuel on European airfields or to<br />

move their own American materials. Some member states on which<br />

Washington most counted had let the usa down badly – meaning, of<br />

course, the uk. The Netherlands, Rush emphasised, absolutely did not<br />

belong to this category. 91 Four days earlier, on October 26, the American<br />

Ambassador had communicated to Van der Stoel the appreciation of his<br />

government for the Dutch attitude during the October war. 92<br />

An American official would later write in the New York Times that<br />

‘the Europeans, with the exception of Portugal and The Netherlands, had<br />

refused to have anything to do with us effort to resupply Israel with<br />

weapons, in some cases denying them overflight and refueling by American<br />

planes’. But this open reference did not go down well with the Dutch<br />

33

Foreign Ministry; for the whole aim was that the Dutch attitude should<br />

remain secret. On November 6, in a request that he should inquire into<br />

various matters of world affairs, the Ambassador in Washington was<br />

asked to advise the Minister how ‘to dispel the wholly incorrect impression<br />

that we allowed overflights and refuelling’. 93<br />

Vredeling recalls that James Schlesinger, American Defense Secretary,<br />

also knew of the Dutch arms deliveries. This was evident in December<br />

1973, when Vredeling spoke with him in The Hague. Schlesinger was fulsome<br />

in his praise of The Netherlands. The American had learned the first<br />

line of the Dutch national anthem Wilhelmus by heart. 94 Van der Stoel<br />