Burgundian Noblemen's Underclothes c1445-1475

Burgundian Noblemen's Underclothes c1445-1475

Burgundian Noblemen's Underclothes c1445-1475

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Burgundian</strong> Noblemen’s <strong>Underclothes</strong> <strong>c1445</strong>-<strong>1475</strong><br />

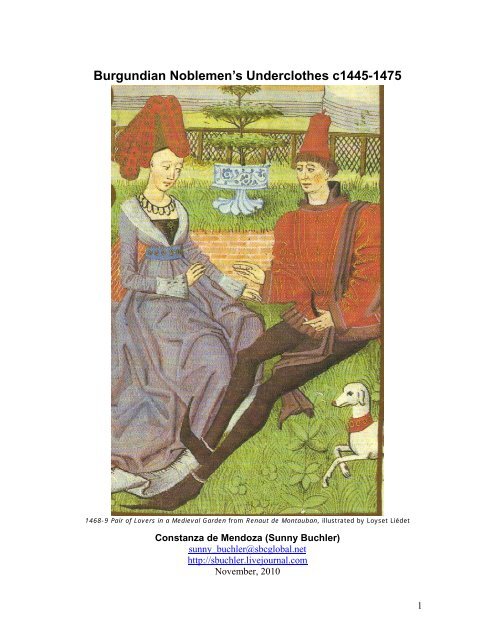

1468-9 Pair of Lovers in a Medieval Garden from Renaut de Montauban, illustrated by Loyset Liédet<br />

Constanza de Mendoza (Sunny Buchler)<br />

sunny_buchler@sbcglobal.net<br />

http://sbuchler.livejournal.com<br />

November, 2010<br />

1

<strong>Burgundian</strong> Noblemen’s <strong>Underclothes</strong> <strong>c1445</strong>-<strong>1475</strong> ........................................................... 1<br />

Overview ......................................................................................................................... 2<br />

The Fashionable Silhouette ......................................................................................... 3<br />

Layers and Fashion Terms .......................................................................................... 4<br />

Underwear ....................................................................................................................... 6<br />

Underpants .................................................................................................................. 6<br />

Shirt ............................................................................................................................. 8<br />

Informal wear/Middle Layer ......................................................................................... 15<br />

Hose/Hosen ............................................................................................................... 15<br />

Doublet ...................................................................................................................... 26<br />

Bibliography ................................................................................................................. 41<br />

Table of Illustrations ..................................................................................................... 42<br />

Overview<br />

Figure 1.1 North-Western Europe in <strong>1475</strong><br />

The dark gray areas show the possessions of the Dukes of Burgundy in <strong>1475</strong> under Charles the Bold. In<br />

<strong>1475</strong> the <strong>Burgundian</strong> territories were at their greatest extent. With the death of Charles in 1477 the<br />

Duchy of Burgundy itself passed to France and the remaining territories to the Holy Roman Empire. 1<br />

The style I’m analyzing is generally called <strong>Burgundian</strong>, although most accurately it is<br />

termed a Franco-Flemish style as it is seen throughout France and the <strong>Burgundian</strong><br />

territories (including Flanders). The term <strong>Burgundian</strong> is usually applied because the<br />

style’s popularity roughly coincides with the brief dominance of the court of Burgundy.<br />

Elements of the <strong>Burgundian</strong> style appear in English fashion, but there are enough quirks<br />

to the English fashions that I have not included English examples in this study.<br />

1 Dunkerton et al. 15<br />

2

The Fashionable Silhouette<br />

Figure 2.1<br />

1447-8 fontpiece to Rogier van der Weyden’s Les Chroniques de<br />

Hainaut<br />

Figure 2.3<br />

1457 King Rene's Book of Love, Folio 51v<br />

Figure 2.2<br />

1450s Burgundy, Guy Parat’s Three Treatises on the Preservation of<br />

Health<br />

Figure 2.4<br />

1465 Loyset Liédet’s Renaud de Montauban , “the Marriage of<br />

Renaut de Montauban and Clarisse”<br />

3

Figure 2.5<br />

1470 frontpiece to Loyset Liédet’s Livre des fais d’Alexandre le<br />

grant, “Vasco de Lucena Presents Book to Charles the Bold of<br />

Burgundy”<br />

Figure 2.6<br />

<strong>1475</strong> Loyset Liédet and Pol Fruit’s Histoire du Charles Martel<br />

Layers and Fashion Terms<br />

Decoding <strong>Burgundian</strong> layers and levels of formality can be confusing if you’re not<br />

already familiar with the layers involved. It may help to compare the layers of a man's<br />

modern business suit to the layers in a <strong>Burgundian</strong> nobleman's formal get-up:<br />

Modern men's business wear <strong>Burgundian</strong> noble's formal attire<br />

Undershirt (optional) Shirt (not optional)<br />

Underwear (e.g. briefs or boxers) Underwear<br />

Dress shirt Doublet<br />

Dress pants Hose/hosen<br />

Suit coat Houppelande/over-gown<br />

Hat (optional, uncommon) Hat<br />

Shoes (not optional) Shoes (optional, but common)<br />

This analogy works relatively well from a formality standpoint; a fellow in a modern<br />

office may remove the jacket and tie and even roll up his sleeves, but that's decidedly less<br />

formal then wearing the full get-up, just like a <strong>Burgundian</strong> fellow may remove his overgown<br />

and belt/pouch etc. and go about in his doublet and hose to do athletic activities,<br />

but it's decidedly less formal and you wouldn’t want to wear either variation in a formal<br />

situation.<br />

The analogy does break down if you look at it from a construction standpoint; the<br />

<strong>Burgundian</strong> shirt is more similar to a modern dress shirt then to any of the other<br />

garments, while a doublet is tailored more like a suit coat. I could’ve drawn the analogy<br />

that an over-gown was like a modern overcoat but that implies something that is only<br />

4

worn outside. Since buildings did not have modern heating systems there doesn’t seem to<br />

have been much difference between what was worn indoors and outdoors:<br />

Figure 3.1<br />

A winter scene from a fifteenth century French Book of Hours<br />

The men in this snowball fight mostly wear the full ensemble of doublet, hose and over-gown, but the<br />

fellow in the center rolling the large snowball has stripped to his doublet, and has even unlaced his hose<br />

from the back of his doublet.<br />

5

Underwear<br />

Underpants<br />

Figure 4.1<br />

Paris, muse du petit palais<br />

L Dut 456 fol18v, Bourgogne<br />

Figure 4.4<br />

1491 Hans Memling, The Passion Triptych<br />

(Gerverade Triptych), center Crucifixion<br />

Figure 4.7<br />

1490 Toledo Museum<br />

Figure 4.2<br />

1470-71 Hans Memling, Scenes from<br />

the Passion of Christ (detail)<br />

Figure 4.5<br />

1485-90 Hans Memling, Triptych with the<br />

Resurrection, left wing showing the<br />

Martyrdom of St. Sebastian<br />

Figure 4.8<br />

Ca. 1430-40 Boccaccio’s Decameron.<br />

Bibliotheque de l’Arsenal, MS 5070.<br />

Figure 4.3<br />

Master of the Bruges<br />

Passion Scenes, found<br />

in Calvary, Bruges, St<br />

Savior’s Church<br />

Figure 4.6<br />

Master of St. Sebastian, St Irene<br />

Healing St Sebastian's Wounds<br />

Figure 4.9<br />

After the Master of Flémalle,<br />

Triptych with the Decent from<br />

the Cross (left panel)<br />

6

*Note, half of these pictures are not from the 1445-75 period, because it’s hard to find good pictures of<br />

underwear. Based on the similarities from before and after our period of interest there doesn’t look like<br />

there’s a huge shift in style or construction.<br />

To start with the obvious observations, just to make sure they’re stated:<br />

� Every illustration I’ve found shows white underpants (so they really are medieval<br />

tighty-whiteies!)<br />

� I see two styles depicted, one type looks similar to modern briefs; the other is<br />

more like shorts with a slit at the side of the leg. Since one image (Figure 2)<br />

shows both being worn, my assumption is that it’s a personal preference thing,<br />

much like boxers vs. briefs today.<br />

� The brief style (and possibly the shorts style, but the pictures of those are less<br />

clear) has some sort of drawstring that gathers the front pouch and ties in the<br />

center front.<br />

� Both styles fit tightly (and smoothly) around the leg and butt.<br />

As a side note, Christ never seems to be depicted in underwear – only a swath of fabric.<br />

However, the thieves crucified with him frequently have underpants, as does St.<br />

Sebastian. This difference is probably due to the story of the soldiers casting lots for<br />

Christ’s clothes.<br />

Master Emrys Eustace, hight Broom suggests a possible construction that I’m rather<br />

enamored of (but have not tried yet):<br />

“The breeches [underpants’] … hem fully enclosed the cord. Wrapping<br />

around more than a full circle of the waistline and overlapping in front, the<br />

ends were pulled back together, gathering the front center. In this way, the<br />

breeches could be well-fitted behind, while there was enough give when<br />

open to make them easy to don. This also created the pouch seen in most<br />

15th c depictions of men stripped to their underclothes.” 2<br />

This pattern that Master Lorenzo Petrucci suggests for Italian brache (Italian boxers from<br />

the same timer period we’re looking at) would work well with using this technique:<br />

Figure 4.10<br />

Master Lorenzo Petrucci’s construction diagram for brache<br />

2 http://www.greydragon.org/library/underwear1.html<br />

7

Shirt<br />

Figure 5.1<br />

Paris, muse du petit palais<br />

L Dut 456 fol18v, Bourgogne<br />

Figure 5.4<br />

Gawain in the Cart<br />

BNF Richelieu Manuscrits<br />

Français 115, Fol. 420<br />

Lancelot du Lac, France,<br />

Ahun, 15 th century, by<br />

Évrard d'Espinques and<br />

collaborators<br />

Figure 5.2<br />

Ca. 1460 P. de Crescens, Le<br />

Rustican<br />

This is a 15th century French<br />

illustration of an agricultural<br />

treatise by a 14th century Italian<br />

naturalist, Peter of Crescenzi<br />

Figure 5.5<br />

Ca. 1465-70 Burges.<br />

Master of the Harley<br />

Froissart, Jean Foissart’s<br />

Chroniques.<br />

Figure 5.6<br />

1470-71 Hans Memling,<br />

Scenes from the Passion<br />

of Christ (detail)<br />

Figure 5.3<br />

Ca. 1450 MS76/1362. Hours of the<br />

Duchess of Bourgogne.<br />

Spectators on the river banks enjoy<br />

scenes of water-tilting<br />

Figure 5.7<br />

1470-71 Hans Memling,<br />

Scenes from the Passion<br />

of Christ (detail)<br />

8

Figure 5.8<br />

Ca. 1454 Master of the Privileges of<br />

Ghent and Flanders, Surrender of<br />

the Burghers of Ghent in 1453 from<br />

the Privileges and Statutes of Ghent<br />

and Flanders, Cod. 2583, fol. 349v<br />

Figure 5.9<br />

Ca. 1473-5 The<br />

Justice of the<br />

Emperor Otto III:<br />

The Execution of<br />

the Innocent Man<br />

by Dirk Bouts<br />

Here is the shirt as it’s worn under other garments:<br />

Figure 5.12<br />

Paris, muse du petit palais<br />

L Dut 456 fol18v, Bourgogne<br />

Figure 5.13<br />

1453-55 Rogier Van Der<br />

Weyden, St. John Alterpiece<br />

Figure 5.10<br />

Ca. 1473-5 The Justice of<br />

the Emperor Otto III: The<br />

Execution of the Innocent<br />

Man by Dirk Bouts<br />

Figure 5.11<br />

Bohort l'Essillié helping<br />

Lambegue<br />

BNF Richelieu Manuscrits<br />

Français 115, Fol. 402<br />

Lancelot du Lac, France,<br />

Ahun, 15 th century, by<br />

Évrard d'Espinques and<br />

collaborators<br />

Figure 5.14<br />

P. de Crescens, Le<br />

Rustican, about 1460.<br />

This is a 15th century<br />

French illustration of<br />

an agricultural<br />

treatise by a 14th<br />

century Italian<br />

naturalist, Peter of<br />

Crescenzi<br />

9

Figure 5.15<br />

Late 15th - Early 16th<br />

cent Book of Simple<br />

Medicine F109r<br />

“Aloe and 2 Kinds of<br />

Celery”<br />

Figure 5.16<br />

Ca.1470-75 “Life of St. Sebastian” (Detail of three<br />

archers). In the style of Jean Canavesio and Jean<br />

Baleison. Wall painting at the chapel of Saint Sebastian,<br />

Saint-Étienne-de-Tinée, Côte d'Azur, France<br />

The neckline of the shirt, as seen through the lacings of the doublet:<br />

Figure 5.18<br />

1447-8 Miniature from page 1 of<br />

Les Chroniques de Hainaut by<br />

Rogier van der Weyden<br />

Figure 5.21<br />

Ca. 1467/70 Portrait of<br />

Anthony of Burgundy<br />

by Hans Memling<br />

Figure 5.22<br />

1462 Dirk Bouts Portrait of an<br />

Unknown Man<br />

Figure 5.19<br />

Ca. 1450 Portrait of Duke Philip<br />

the Good of Burgundy by Rodger<br />

van der Weyden<br />

Figure 5.23<br />

Before 1478, Hans Memling<br />

(possibly), Portrait of<br />

Jacques of Savoy<br />

Figure 5.17<br />

Ca. 1473-5 The Justice of the<br />

Emperor Otto III: The Execution of<br />

the Innocent Man by Dirk Bouts<br />

Figure 5.20<br />

1469 St. Eligius, as a Goldsmith,<br />

Hands the Wedding Couple a Ring by<br />

Petrus Christus.<br />

Figure 5.24<br />

Ca. 1445-48 Rogier van der<br />

Wyden, Middeburg Altarpiece<br />

(central panel)<br />

10

Again, let’s start with the obvious observations:<br />

� Every illustration I’ve found shows a white shirt<br />

� The length comes to between mid-thigh and mid-calf (note that Figures 12-14<br />

showing the length under a short doublet are the shorter length)<br />

� The sleeves are loose, but not too full, and they end at the wrist.<br />

� There is no obvious gathering at the sleeve head. The sleeve might be eased into<br />

the armhole or it might be constructed with a gusset.<br />

� The shirt is loose, and hangs relatively straight (there are probably side gores, but<br />

there are not any front gores.)<br />

� The shirt does not appear to be gathered at the neck or wrists in any way<br />

� A center front opening cannot be seen when it’s worn under the doublet (an<br />

important observation for figuring out how the neckline works)<br />

Most extant shirt and tunics have round necklines, however, I have had no luck using<br />

round necklines to replicate the neckline seen through the lacings at the clavicle (or<br />

higher) in many of the <strong>Burgundian</strong> portraits (Figures 16-21). In my experience, round<br />

necklines that are big enough to slip over the head have a tendency to dip lower on the<br />

neck then the pictures show. This leads me to look at other possible constructions:<br />

– The shirt has a very small round neckline (necessitating a slit opening<br />

someplace other then center front (such as the shoulder seam or a side<br />

front opening).<br />

– The shirt has a horizontal slit opening (a.k.a. a shallow “boat” neckline).<br />

– The shirt has a neckline with a gusset similar to Master Lorenzo Petrucci’s<br />

reconstruction of Italian shirts from the same period.<br />

Arguments for the “boat” neckline:<br />

There is an extant shirt with a “boat” neckline, the Rogart shirt (see figure 25 below).<br />

This shirt is not from this time and place (it’s from 14 th century Scotland), but it does<br />

suggest a potential neck-hole construction to try, which was at least used once in<br />

medieval Europe.<br />

11

Figure 5.25<br />

Image Copyright © I. Marc Carlson 1999<br />

The Rogart shirt which was found in a grave near Springhill, Knockan, Parish of<br />

Rogart, Sutherland (Scotland) and has been tentatively dated to the 14th century<br />

A couple of the shirts could arguably be showing a boat neckline (although it’s very hard<br />

to differentiate a boat neck from a round neck when it’s all loose…)<br />

Figure 5.26<br />

Ca. 1450 MS76/1362. Hours of the Duchess of<br />

Bourgogne.<br />

Spectators on the river banks enjoy scenes of watertilting<br />

Figure 5.27<br />

Paris, muse du petit palais<br />

L Dut 456 fol18v,<br />

Bourgogne<br />

12

Arguments for the high round neckline with an off-center slit<br />

I found multiple pictures of a shirt that looked like it had a slit slightly to the (wearer’s)<br />

front left (see pictures below).<br />

Figure 5.28<br />

Paris, muse du petit palais<br />

L Dut 456 fol18v, Bourgogne<br />

This may be showing a neckline<br />

with a slit or it may be showing a<br />

fold of fabric at the neck.<br />

Figure 5.29<br />

P. de Crescens, Le Rustican,<br />

about 1460.<br />

This is a 15th century French<br />

illustration of an agricultural<br />

treatise by a 14th century<br />

Italian naturalist, Peter of<br />

Crescenzi<br />

Figure 5.30<br />

Folie de Lancelot<br />

BNF Richelieu Manuscrits<br />

Français 116, Fol. 598v<br />

Lancelot du Lac, France, Ahun,<br />

XVe siècle, Évrard d'Espinques<br />

et collaborateurs<br />

There are two extant garments that have an off-center slit in the neck hole, but neither of<br />

them is remotely close to the <strong>Burgundian</strong> time-period:<br />

Figure 5.31<br />

Image Copyright © I. Marc Carlson 2003<br />

Front panels of the Gown of St. Elizabeth of Thuringia,<br />

dated to about 1230.<br />

Figure 5.32<br />

Image Copyright © I. Marc Carlson 2002<br />

This shirt was supposedly owned by Thomas Becket (1120-1170)<br />

and is now in the Cathedral of Arras<br />

13

Arguments for a gusseted neckline<br />

There is persuasive visual evidence for a shirt with a gusseted neckline in Italy during<br />

this period; however, most of the <strong>Burgundian</strong> portraits that show the characteristic foldover<br />

are after <strong>1475</strong>. This construction could provide the flat expanse across the<br />

collarbones (beneath the top lacing) without slipping down.<br />

Figure 5.33<br />

Master Lorenzo Petrucci’s construction diagram for an<br />

Italian camicia<br />

Figure 5.36<br />

1480 Hans Memling, Portrait of a Man with a Roman Coin<br />

Figure 5.34<br />

1452-66 Italy. Piero della Francesca,<br />

Discovery of the True Cross (detail)<br />

Figure 5.37<br />

1480 Hans Memling, Portrait of a man<br />

with a Letter<br />

Figure 5.35<br />

<strong>1475</strong> Italy. Antonello da Messina,<br />

Portrait of a Man<br />

Figure 5.38<br />

Paris, muse du petit palais<br />

L Dut 456 fol18v, Bourgogne<br />

This may be showing a neckline<br />

with a slit or it may be showing<br />

the gusset folded over.<br />

14

Informal wear/Middle Layer<br />

Hose/Hosen<br />

Hose is the term I use for leggings whose legs are sewn together. I use the term hosen to<br />

indicate leggings whose legs are separate, and joined only by attaching the codpiece.<br />

Sometimes it’s hard to tell which version is being worn in the illustrations, if I cannot tell<br />

I default to using the term hose to describe the leggings..<br />

Figure 6.1<br />

1465 Loyset Liédet’s Renaud de<br />

Montauban , “the Marriage of<br />

Renaut de Montauban and<br />

Clarisse”<br />

Figure 6.2<br />

1465 Loyset Liédet’s Renaud de<br />

Montauban<br />

Figure 6.3<br />

1470-71 Hans Memling, Scenes<br />

from the Passion of Christ<br />

(detail)<br />

Figure 6.4<br />

Ca. 1465-70 Burges. Master of<br />

the Harley Froissart, Jean<br />

Foissart’s Chroniques.<br />

15

Figure 6.5<br />

Paris, muse du petit palais<br />

L Dut 456 fol18v, Bourgogne<br />

Figure 6.8<br />

Mid-15th century France. Le Livre<br />

des Simples Medecines<br />

Figure 6.6<br />

1453-55 Rogier Van Der Weyden,<br />

St. John Alterpiece<br />

Figure 6.9<br />

1452-60 Jean Fouquet’s Hours of<br />

Etienne Chevalier. “The Martyrdom<br />

of St Apollonia”<br />

Figure 6.7<br />

1470-71 Hans Memling,<br />

Scenes from the Passion<br />

of Christ (detail)<br />

Figure 6.10<br />

1470-71 Hans Memling,<br />

Scenes from the Passion<br />

of Christ (detail)<br />

16

Figure 6.11<br />

1474-79 Hans Memling,<br />

Altarpiece of Saint John the<br />

Baptist and Saint John the<br />

Evangelist. Left panel, “Beheading<br />

of Saint John the Evangelist.”<br />

Figure 6.13<br />

Late 15th - Early 16th cent Book<br />

of Simple Medicine F109r<br />

“Aloe and 2 Kinds of Celery”<br />

Figure 6.12<br />

Figure 6.14<br />

Note, there is no change to<br />

the color of the sole, as one<br />

might expect from leather<br />

soles.<br />

Figure 6.15<br />

1473 Paris, Maitre Francois, St Augustine's<br />

City of God<br />

Here are the questions about hose that I started with:<br />

1. Are the legs separate or sewn together across the butt?<br />

2. Do the hose have attached feet?<br />

3. Do the hose feet have soles that are reinforced so that they can be worn outside<br />

without shoes (e.g. is there a leather sole)?<br />

4. Where are the lacing holes that attach the hose to the doublet placed?<br />

17

5. What is the shape of the codpiece?<br />

6. What is the shape of the feet?<br />

7. Where are the seams and how are the hose constructed?<br />

I’ll take each of these in order:<br />

1. Are the legs separate or sewn together across the butt?<br />

Figures 5-9 obviously have one leg separate from the other (they can be removed<br />

separately or rolled down. However figures 10-12 are just as obviously joined hose<br />

(separate legs would fall down like in Figure 7 if the center back point was released).<br />

Since figures 7 and 10 come from the same painting, I conclude that this time period was<br />

a transition era between the styles and both could be found. I hypothesize that earlier in<br />

this era the split hose were more common and later the joined hose were more common.<br />

My reasoning is due to joined hose being predominate at the turn of the 16 th century, and<br />

that there was an impetus towards the hose covering the butt due to the rise in the<br />

hemline of the over-gown from mid-thigh to mid-butt between 1445 and <strong>1475</strong>. If you<br />

choose to do split hose, be aware that the underwear will show occasionally, as in this<br />

Italian picture:<br />

Figure 6.16<br />

1452-66 Piero della Francesca, Battle<br />

between Heraclius and Chosroes (detail)<br />

2. Do the hose have attached feet?<br />

Hose are worn with shoes in the majority of the pictures showing feet, making this<br />

question difficult to be sure of the answer. I have found no pictures that show hose being<br />

cut off at the ankle (although there are some in Italian art). Figure 12 shows a stirrup<br />

rather then a full foot. If shoes are not worn over the hosen, then almost always the hose<br />

have feet attached, as in Figure 5, 13, 14 & 15. There are a number of fragments of extant<br />

hose (although I know of none from this period for northern Europe); most of the extant<br />

pieces have feet (or the remains thereof). See Marc Carlton’s website for a summary:<br />

18

http://www.personal.utulsa.edu/~marc-carlson/cloth/hose.html . Occasionally there is the<br />

suggestion of socks being worn with hose (the white ring around the top of the shoe in<br />

figure 1) but those may be worn for warmth and so we cannot use them to say whether<br />

the hose beneath them has feet attached.<br />

3. Do the hose feet have soles that are reinforced so that they can be worn<br />

outside without shoes? (I.E. is there a leather sole?)<br />

Most of the time the hose are worn with shoes, so there would be no need of a reinforced<br />

sole, and it might be uncomfortable when worn with shoes. However, there are a<br />

relatively small number of pictures showing hose intentionally worn without shoes while<br />

outside doing work (figures 13-15) and it is logical to assume that these hose have<br />

reinforced soles. Figure 14 shows the bottom of the foot, and if there was reinforced<br />

leather soles you would expect there to be a difference in color; there is no color<br />

difference. I have found no pictures that show a sole that is markedly different from the<br />

body of the hose.<br />

4. Where are the lacing holes that attach the hose to the doublet placed?<br />

There aren’t very many pictures showing the points (laces between hose and doublet),<br />

and there is some variation between the depictions. However, joined hose mostly seem to<br />

have center back points, and side or side-back points, and side-front points:<br />

Figure 6.17<br />

1470-71 Hans Memling,<br />

Scenes from the Passion of<br />

Christ (detail)<br />

Figure 6.20<br />

Ca. 1473-5 The Justice of<br />

the Emperor Otto III: The<br />

Execution of the Innocent<br />

Man by Dirk Bouts<br />

Figure 6.18<br />

Figure 6.21<br />

Hercule participant aux jeux<br />

BNF Richelieu Manuscrits Français 59, Fol.<br />

111v<br />

Raoul Lefèvre, Histoires de Troyes,<br />

Belgique, XVe siècle<br />

Figure 6.19<br />

Late 15th - Early 16th cent Book of Simple<br />

Medicine F109r “Aloe and 2 Kinds of Celery”<br />

Figure 6.22<br />

Ca. 1470-75 “Life of St. Sebastian” (Detail<br />

of three archers). In the style of Jean<br />

Canavesio and Jean Baleison. Wall painting<br />

at the chapel of Saint Sebastian, Saint-<br />

Étienne-de-Tinée, Côte d'Azur, France<br />

19

Figure 6.23<br />

1465 Loyset Liédet’s<br />

Renaud de Montauban<br />

Figure 6.26<br />

Late 15th-early 16th cent<br />

France. Book of Simple<br />

Medicine F140r<br />

Figure 6.24<br />

Ca. 1465-70 Burges. Master of the Harley<br />

Froissart, Jean Foissart’s Chroniques.<br />

Figure 6.25<br />

1473 Paris, Maitre Francois, St Augustine's<br />

City of God<br />

A random observation: most of the time that the points (lacing between<br />

hose and doublet) are visible the individual is engaged in some strenuous<br />

activity (like beheading someone). In the vast majority of these cases when<br />

we can see the center back point, it is undone. This makes sense as releasing<br />

the center back point makes it much easier to bend over.<br />

Another thing to point out, the points do not look to be tied with bow ties.<br />

See http://www.florentine-persona.com/tying_bows.html for how to tie<br />

them.<br />

5. What is the shape of the codpiece?<br />

Figure 6.27<br />

Ca. 1470-75 “Life of St. Sebastian” (Detail of three<br />

archers). In the style of Jean Canavesio and Jean<br />

Baleison. Wall painting at the chapel of Saint Sebastian,<br />

Saint-Étienne-de-Tinée, Côte d'Azur, France<br />

Figure 6.28<br />

1471 France, Loyset Liédet,<br />

“Tree of Consanguinity” from<br />

Somme rurale de Jean<br />

Boutillier.<br />

MS Fr. 202, fol. 15v<br />

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris<br />

Figure 6.29<br />

Ca. 1473-5 The Justice of the<br />

Emperor Otto III: The<br />

Execution of the Innocent<br />

Man by Dirk Bouts<br />

20

Figure 6.30<br />

Late 15th-early 16th century, France. Book of Simple<br />

Medicine F140r<br />

Figure 6.31<br />

1465 Loyset Liédet’s Renaud<br />

de Montauban , “the Marriage<br />

of Renaut de Montauban and<br />

Clarisse”<br />

Figure 6.32<br />

1473 Paris, Maitre Francois,<br />

St Augustine's City of God<br />

The shape of the codpiece varies quite a bit; figure 27 looks like an un-seamed, roughly<br />

triangular flap, whereas figures 28-31 have a seam down the center and appear to be<br />

much more sports-cup-like in shape. Figure 32 has yet a different shape, being a wider<br />

triangle then figures 28-31 but having a suggestion of the shaped item that the codpiece<br />

becomes in the Tudor era. However, the most common shape depicted is similar to<br />

figures 28- 31.<br />

6. What is the shape of the feet?<br />

Figure 6.33<br />

<strong>1475</strong> Loyset Liédet and Pol<br />

Fruit’s Histoire du Charles<br />

Martel<br />

Figure 6.34<br />

1447-8 Miniature, illustration from page 1 of Les<br />

Chroniques de Hainaut by Rogier van der Weyden<br />

Figure 6.35<br />

Ca. 1450 MS76/1362. Hours of the Duchess of<br />

Bourgogne.<br />

Spectators on the river banks enjoy scenes of watertilting<br />

Figure 6.36<br />

1465 Loyset<br />

Liédet’s Renaud de<br />

Montauban , “the<br />

Marriage of Renaut<br />

de Montauban and<br />

Clarisse”<br />

21

Figure 6.37<br />

1465 Loyset Liédet’s Renaud<br />

de Montauban , “the Marriage<br />

of Renaut de Montauban and<br />

Clarisse”<br />

Figure 6.40<br />

late 15th century Egerton MS<br />

2019f5 Book of Hours<br />

Is this a picture of hose with<br />

spurs attached?<br />

Figure 6.38<br />

Paris, muse du petit palais<br />

L Dut 456 fol18v, Bourgogne<br />

Figure 6.41<br />

Late 15th - Early 16th century. Book of Simple<br />

Medicine F109r “Aloe and 2 Kinds of Celery”<br />

Figure 6.42<br />

1473 Paris, Maitre Francois, St Augustine's City of<br />

God<br />

(Left) Detail of a laborer’s foot.<br />

(Right) Detail of nobles foot.<br />

Figure 6.39<br />

Reconstruction de<br />

Troie<br />

Français 59 , Fol.<br />

238<br />

Raoul Lefèvre,<br />

Histoires de<br />

Troyes, Belgique,<br />

XVe siècle<br />

Figure 6.43<br />

Alexandre malade<br />

Cote : Français 47<br />

, Fol. 46v<br />

Quinte-Curce,<br />

Histoire<br />

d'Alexandre le<br />

Grand (traduction<br />

de Vasque de<br />

Lucène), Belgique,<br />

Flandre, XVe siècle<br />

* the assumption in all these pictures is that if the feet match the legs, then the feet are part of the hose;<br />

this may not be accurate, especially with the black hose (as the most common color for shoes seems to be<br />

black).<br />

The foot shape seems to vary: figures 33-37 have extremely pointy toes. Figures 38 and<br />

39 have mildly pointed toes and figures 41 & 43 have blunt, feet-shaped toes. Not enough<br />

of these pictures have specific dates attached to be sure, but it is my belief that the shape<br />

of the toes (on the noblemen) varies over time – that they start out in the 1450s being<br />

very pointed and by the end of the century have become blunt. Regardless, working<br />

men’s feet and shoes tend to be noticeably blunter then noblemen’s feet (figure 42).<br />

22

Construction-wise, if you have a separate sole for the hose, it’s very easy to do rounded<br />

or “blunt” toes. If you use the more common (in the extant hose fragments) leg-stirrup<br />

piece with a second piece for the toes it’s very easy to get pointy toes. (See figure 44<br />

below.) Using this construction it’s actually very difficult to get non-pointy toes.<br />

Figure 6.44<br />

Image Copyright © I. Marc Carlson 1998<br />

An example of Nockert Hose Type 4:<br />

"Short hose with a strap. This hose is cut in one piece with a seam at the back, and an<br />

opening for the foot at the bottom. The two side pieces thus formed at the bottom were<br />

sewn together to make a strap beneath the foot." 3<br />

7. Where are the seams and how are the hose constructed?<br />

There is no pictorial evidence for how the foot of the hose were constructed. There are<br />

occasional pictures that show center back leg seams:<br />

3 I. Marc Carlson, http://www.personal.utulsa.edu/~marc-carlson/cloth/hstype4.html [Nov. 7, 2010]<br />

23

Figure 6.45<br />

Fouquet miniature showing the trial of the duc d'Alencon<br />

Figure 6.46<br />

1453-55 Rogier Van Der Weyden, St. John Alterpiece<br />

Notice the seam allowance showing at the center back of the hosen on<br />

the right.<br />

There are some lovely pictures from the early 1500s showing the butt seams for joined<br />

hose, but I have found none from the period we’re discussing.<br />

As far as lining goes, figures 46-48 clearly show that at least the top part of the hosen was<br />

lined. However, figures 46 and 49 show cases where the top part of the hose was not<br />

lined. There is an Italian picture that shows the lining only being at the top of the hose<br />

(figure 51) but I have not found an equivalent picture for northern Europe.<br />

24

Figure 6.47<br />

Mid-15th century, France. Le Livre des<br />

Simples Medecines<br />

Figure 6.50<br />

Late 15th-early 16th century,<br />

France. Book of Simple Medicine<br />

F140r<br />

Figure 6.48<br />

1452-60 Jean Fouquet’s Hours of<br />

Etienne Chevalier. “The Martyrdom<br />

of St Apollonia”<br />

Figure 6.51<br />

1455 Italy. Piero della Francesca, Burial of<br />

the Holy Wood<br />

Figure 6.49<br />

1470-71 Hans Memling, Scenes<br />

from the Passion of Christ (detail)<br />

In general, I recommend Master Emrys Eustace, hight Broom’s work for a much more<br />

comprehensive look at constructing hose then I have done:<br />

http://www.greydragon.org/library/underwear3.html<br />

25

Doublet<br />

Body<br />

Figure 7.1<br />

1465 Loyset Liédet’s Renaud de<br />

Montauban , “the Marriage of<br />

Renaut de Montauban and<br />

Clarisse”<br />

Figure 7.3<br />

1465 Loyset Liédet, Bertha<br />

Duchess of Burgundy building a<br />

church<br />

Figure 7.2<br />

Ca. 1470-75 “Life of St. Sebastian” (Detail of three archers). In the style of Jean<br />

Canavesio and Jean Baleison. Wall painting at the chapel of Saint Sebastian, Saint-<br />

Étienne-de-Tinée, Côte d'Azur, France<br />

Figure 7.4<br />

Ca. 1465-70 Burges. Master of<br />

the Harley Froissart, Jean<br />

Foissart’s Chroniques.<br />

Figure 7.5<br />

Ca. 1450 Hours of the Duchess of Bourgogne,<br />

youths playing hockey<br />

26

Figure 7.6<br />

Figure 7.7<br />

Ca. 1473-5 Dirk<br />

Bouts, The Justice of<br />

the Emperor Otto<br />

III: The Execution of<br />

the Innocent Man<br />

Figure 7.8<br />

1474-79 Hans Memling,<br />

Altarpiece of Saint John<br />

the Baptist and Saint<br />

John the Evangelist.<br />

Left panel, “Beheading<br />

of Saint John the<br />

Evangelist.”<br />

Figure 7.9<br />

Paris, muse du petit palais<br />

L Dut 456 fol18v, Bourgogne<br />

Figure 7.10<br />

Fouquet miniature showing the<br />

trial of the duc d'Alencon<br />

27

Figure 7.11<br />

1466-7 Loyset Liédet, Gerard de<br />

Roussillon and his wife Berthe<br />

are presented to Charles the<br />

Bold<br />

Figure 7.12<br />

Ca. 1450, MS76/1362. Hours of the Duchess of<br />

Bourgogne. Spectators on the river banks enjoy<br />

scenes of water-tilting<br />

Figure 7.13<br />

1470-71 Hans Memling, Scenes<br />

from the Passion of Christ<br />

Some basic observations:<br />

1. The vast majority of doublets where the front can be seen, the front opening is a<br />

narrow open V. In fact, in the two figures which seem to depict a closed doublet<br />

(figure 10 and 11) I’m not sure the garment we’re looking is the doublet rather<br />

then an over-gown that is similar in shape to a doublet. In pictures where the front<br />

is covered by an over-gown and only the collar is visible, it is rare for the edges of<br />

the collar to meet (for example, figure 14), which in my mind is suggestive of the<br />

hidden doublet beneath having a V front, as are the number of pictures showing<br />

the over-gown open and displaying a white shirt (figure 15).<br />

Figure 7.14<br />

Ca. 1465-70 Burges. Master of the<br />

Harley Froissart, Jean Foissart’s<br />

Chroniques.<br />

Figure 7.15<br />

1447-8 Miniature, illustration from page 1 of Les Chroniques<br />

de Hainaut by Rogier van der Weyden<br />

2. The lacing down the V front is decorative in nature, frequently having a pair of<br />

lacing cords at the neck followed by a space. There may or may not be ties<br />

28

etween the neck tie and the waist tie. The waist tie is frequently not shown but<br />

the tapering closure plus the tight fit at the waist leads me to believe that there is a<br />

waist tie, even if it’s not shown.<br />

3. The waist is (by current fashion standards) quite high; seemingly just below the<br />

ribcage. The vast majority of doublets seem to have a well defined waist<br />

(probably with a waist seam) and a peplum that goes over the hips. Figure 13<br />

doesn’t have these characteristics, but the figure portrayed is torturing Christ and<br />

so probably doesn’t classify as a nobleman. I believe the waist-seam-less version<br />

of the doublet is a holdover from the earlier “cotehardie” styles that were worn<br />

right up until the start of the <strong>Burgundian</strong> period. The waist-seam-less style is seen<br />

commonly on Italian noblemen of this period, but not so much on <strong>Burgundian</strong><br />

nobles.<br />

4. The silhouette is quite barrel-chested (sometimes referred to as pigeon breasted).<br />

Since most men are not that barrel-chested, it suggests padding to me, especially<br />

with the exaggerated curve towards the waist. The pourpoint of Charles of Blois is<br />

heavily quilted, and there are multiple padded doublets described by Janet Arnold<br />

in Patterns of Fashion, so it is not unreasonable to assume the technique was<br />

available to <strong>Burgundian</strong> tailors.<br />

5. The collars in figures 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, and 12 are a different color from the body of<br />

the doublet, suggesting that they could be a decorative and/or contrasting element.<br />

However, figure 2 also shows a doublet whose collar is the same color as the<br />

body, so it is not required that the collar be a different color.<br />

6. Most of these pictures do not suggest seam-lines, but figure 2 clearly indicates<br />

both a V-shaped base to the collar and a center back seam. The few pictures that<br />

show the inside of the doublet confirm this interpretation:<br />

Figure 7.16<br />

1485-90 Hans Memling, Triptych with the Resurrection, left wing showing the Martyrdom of St. Sebastian<br />

These are the same picture, just from two different books.<br />

29

Figure 7.17<br />

1453-55 Rogier Van Der Weyden, St. John Alterpiece<br />

7. The shape of the front of the collar can be many different shapes, from a gentle<br />

curve to a sharp boxy angle. See figures 20-23 for examples.<br />

8. Look at figures 6.17-6.26 (page 19) in the hose section to see where on the<br />

peplum the points attach. Generally it looks like the eyelets are at the bottom edge<br />

of the doublet, on the hips and definitely below the waist.<br />

30

9. Most illustrations obscure the bottom front of the doublet, however there are at<br />

least 3 shapes seen:<br />

� An inverted V (figure 18)<br />

� Straight across the front (figure 19)<br />

� Open (figure 20)<br />

Figure 7.18<br />

1470-71 Hans Memling, Scenes<br />

from the Passion of Christ<br />

Figure 7.19<br />

Ca. 1450, MS76/1362. Hours of the<br />

Duchess of Bourgogne. Spectators on<br />

the river banks enjoy scenes of watertilting<br />

Figure 7.20<br />

Ca. 1473-5 Dirk Bouts,<br />

The Justice of the<br />

Emperor Otto III: The<br />

Execution of the Innocent<br />

Man<br />

10. Figures 16-18, 21 and 24 suggest that the doublets were laced though eyelet holes,<br />

however figures 22 and 23 suggest the use of eyelet rings, both were probably<br />

used.<br />

Figure 7.21<br />

<strong>1475</strong>? Hans Memling, Martyrdom of St.<br />

Sebastian<br />

Figure 7.23<br />

1462 Dirk Bouts Portrait of<br />

an Unknown Man<br />

Figure 7.24<br />

Before 1478, Hans Memling<br />

(possibly), Portrait of<br />

Jacques of Savoy<br />

Figure 7.22<br />

Ca.1467/70 Portrait of Anthony of Burgundy<br />

by Hans Memling<br />

Figure 7.25<br />

Ca. 1445-48 Rogier van der<br />

Wyden, Middeburg Altarpiece<br />

(central panel)<br />

31

11. Figures 16-18 and 21 all show that the doublet was lined. From the artwork alone<br />

we can’t say what they were lined with (although all 4 are lined with a light<br />

color). However,<br />

“some ordinances of 1520s from the Spanish city of Seville regulated what types<br />

of fabrics could be used in completing a doublet…Expensive outer cloths, such as<br />

brocades, required three linings: ‘one of linen colored like the [fabric], another of<br />

coarse canvas and a third of white linen.’ [5] Doublets of ‘minor silks’ had only<br />

two linings, one canvas and one linen for the body and a white linen and fabriccolored<br />

linen for the sleeves. [6] Cotton was used to stuff the expensive doublets,<br />

but cheaper fustian doublets could be stuffed with wool. Given the body-shaping<br />

function and the need for a strong support for the hose, it is quite likely that the<br />

requirements for 15th century doublets were similar to these given here.” 4<br />

Sleeves<br />

It is my contention that the sleeves are the key to the <strong>Burgundian</strong> nobleman’s silhouette,<br />

namely the very high poof at the top of the arm. It is my belief that this sleeve-puff is<br />

padded and is what supports the over-gown in the super-broad shoulder look which<br />

characterizes <strong>Burgundian</strong> style c.1445-75. After <strong>1475</strong> you start seeing instances of<br />

noblemen wearing doublets without sleeve puffs and the silhouette moves to a much<br />

more narrow look; but during this period, most of the men (with visible sleeves) that do<br />

not have the puff at the top are obviously working-class fellows.<br />

There are very few nobles in the 1445-75 era that are shown without sleeve puffs. The<br />

silhouette in both illuminations and portraiture suggest a larger-then-normal shoulder<br />

breadth (although most individuals’ sleeve heads were obscured by the over-gown). Here<br />

are examples showing the sleeve puff:<br />

4 http://www.nachtanz.org/SReed/doublets.html Susan Reed, “15th-Century Men’s Doublets: An<br />

Overview”. Both references are to Anderson, Ruth M. Hispanic Costume: 1480-1530. New York: Hispanic<br />

Society of America, 1979. Page 55.<br />

32

Figure 7.26<br />

late 1440s-late 1460s Louis of Savoy,<br />

from a statuette on the tomb of Louis<br />

de Mâle<br />

Figure 7.29<br />

Ca. 1460 from Chronique a brégée<br />

des empereurs<br />

Figure 7.27<br />

Ca. 1450 Hours of the Duchess of<br />

Bourgogne, youths playing hockey<br />

Figure 7.30<br />

1465 Loyset Liédet’s Renaud de<br />

Montauban , “the Marriage of Renaut<br />

de Montauban and Clarisse”<br />

Figure 7.28<br />

Ca. 1460 from Chronique a brégée des<br />

empereurs<br />

Figure 7.31<br />

1446 Petrus Christus, Portrait of<br />

Eddward Grimston<br />

33

Figure 7.32<br />

pre-1466 Wavrin Master's cartoons for<br />

L'histoire de Girart de Nevers<br />

Girart is drinking poison<br />

Figure 7.35<br />

1470 Loyset Liédet, Vasco de Lucena<br />

Presents Book to Charles the Bold of<br />

Burgundy<br />

Figure 7.33<br />

1466-7 Loyset Liédet, Gerard de<br />

Roussillon and his wife Berthe are<br />

presented to Charles the Bold<br />

Figure 7.36<br />

1471 France, Loyset Liédet, “Tree of<br />

Consanguinity” from Somme rurale<br />

de Jean Boutillier.<br />

MS Fr. 202, fol. 15v<br />

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris<br />

Sleeve Puff<br />

The shape of the sleeve puff varies quite a lot:<br />

Figure 7.38<br />

1465 Loyset Liédet’s Renaud de<br />

Montauban<br />

Figure 7.39<br />

Ca. 1450 Hours of the Duchess of<br />

Bourgogne, youths playing<br />

hockey<br />

Figure 7.34<br />

1470 Loyset Liédet, Vasco de Lucena<br />

Presents Book to Charles the Bold of<br />

Burgundy<br />

Figure 7.37<br />

<strong>1475</strong> from Histoire du Charles Martel<br />

Figure 7.40<br />

Fouquet miniature showing the<br />

trial of the duc d'Alencon<br />

34

Figure 7.41<br />

1465 Loyset Liédet, Bertha<br />

Duchess of Burgundy building a<br />

church<br />

Figure 7.44<br />

1465 Loyset Liédet, Bertha<br />

Duchess of Burgundy building a<br />

church<br />

Figure 7.42<br />

1470 Loyset Liédet, Vasco de<br />

Lucena Presents Book to Charles<br />

the Bold of Burgundy<br />

Figure 7.45<br />

late 1440s-late 1460s Louis of<br />

Savoy, from a statuette on the<br />

tomb of Louis de Mâle<br />

Figure 7.43<br />

1465 Loyset Liédet’s Renaud de<br />

Montauban , “The Marriage of<br />

Renaut de Montauban and<br />

Clarisse”<br />

Figure 7.46<br />

pre-1466 Wavrin Master's<br />

cartoons for L'histoire de Girart<br />

de Nevers<br />

Some observations:<br />

1. The sleeve puff never comes lower then mid-bicep, and tends to be a bit higher.<br />

2. The puff doesn’t stand up much, mostly is stands out, to the side of the arm, its<br />

aim is to give width rather then height. (Be careful about this when stuffing your<br />

puffs, it’s very easy to get off.)<br />

3. In figures 38-40 the shape of the puff around the arm is not evenly distributed – it<br />

arches around the arm. In figures 41-46 the puff does appear to be gathered<br />

evenly around the arm.<br />

4. How full/stuffed the puff is varies considerably.<br />

Sleeve Closures<br />

All of the sleeves in the pictures above are very tight from the wrist to the uppers arm.<br />

So, how are the sleeves fastened to achieve this? I see two options:<br />

� A discreet fastening method at the wrist.<br />

� A slit up the back of the arm held closed by decorative lacing.<br />

Figure 7.47<br />

Ca. 1450 Hours of the Duchess of<br />

Bourgogne, youths playing hockey<br />

Figure 7.48<br />

1457 King Rene's Book of Love<br />

Folio 51v<br />

Figure 7.49<br />

1465 Loyset Liédet’s Renaud de<br />

Montauban<br />

35

Figure 7.50<br />

1465 Loyset Liédet, Bertha Duchess of<br />

Burgundy building a church<br />

Figure 7.53<br />

1466-7 Loyset Liédet, Gerard de<br />

Roussillon and his wife Berthe are<br />

presented to Charles the Bold<br />

Figure 7.56<br />

Fouquet miniature showing the<br />

trial of the duc d'Alencon<br />

Figure 7.51<br />

1465 Loyset Liédet’s Renaud de<br />

Montauban , “The Marriage of<br />

Renaut de Montauban and<br />

Clarisse”<br />

Figure 7.54<br />

1470 Loyset Liédet, Vasco de<br />

Lucena Presents Book to Charles<br />

the Bold of Burgundy<br />

Figure 57<br />

1487 Hans Memling, Diptych of<br />

Maarten van Nieuwenhove<br />

Figure 7.52<br />

1465 Loyset Liédet, Bertha Duchess of<br />

Burgundy building a church<br />

Figure 7.55<br />

1470 Le Mesnagier de la ville et des<br />

champs<br />

Figure 58<br />

1453-55 Rogier Van Der Weyden, St. John<br />

Alterpiece<br />

36

Figures 47-56 above have no visible fastening. These may be fastened with discrete<br />

lacing like in figure 57 (which is slightly later then our period of interest) or they may<br />

have small self-fabric button closures. Figure 58 shows a man with a single button<br />

closure at the wrist. There are multiple pictures of women with skin tight sleeves that<br />

have a row of small buttons along their outer arm; buttons that are only noticeable when<br />

the picture is enlarged farther then is usually seen in modern art books. Men’s fashion<br />

may have employed this option as well.<br />

Figure 7.59<br />

Ca. 1440-45 Rogier van der Weyden, Visitation of Mary (detail)<br />

There is an almost equally common option for achieving the skin-tight sleeve: a slit up<br />

the side/back of the arm that is held closed with a decorative lacing pattern:<br />

Figure 7.60<br />

1457 King Rene's Book of Love Folio<br />

25v<br />

Figure 7.63<br />

1460-70 Flanders, Histoire de la Belle<br />

Helene<br />

Figure 7.61<br />

1457 King Rene's Book of Love<br />

Folio 31v<br />

Figure 7.64<br />

Figure 7.62<br />

Brussles, Master of the<br />

Legend of St Barbara,<br />

unknown couple<br />

37

Figure 7.65<br />

1460-65 Livres des Tournois du roi<br />

Rene, king-at-arms presenting a<br />

sword to the Duke of Bourbon<br />

Figure 7.68<br />

Ca. 1460 from Chronique a brégée<br />

des empereurs<br />

Figure 7.66<br />

Mid-fifteenth century. Roman de<br />

la Violette. Paris, Bib. Nat. ms fr.<br />

24376 f. 5,8.<br />

Figure 7.69<br />

late 1440s-late 1460s Louis of<br />

Savoy, from a statuette on the<br />

tomb of Louis de Mâle<br />

Figure 7.67<br />

Ca. 1465-70 Burges. Master<br />

of the Harley Froissart, Jean<br />

Foissart’s Chroniques.<br />

Most of the time (when the full sleeve is visible) the slit goes from the wrist nearly to the<br />

sleeve puff (figures 62-69). In figures 65 the slit seems to disappear just above the elbow.<br />

In all cases except 68 the slit appears narrow, as if a seam were left open, rather then a<br />

portion of the sleeve that has been removed. Because of the prevalence of the slit, I<br />

conjecture that there is a seam running up the outer arm, as there is in the extant 14 th<br />

century Charles of Blois' pourpoint (figure 70).<br />

There are many possible ways to construct the tight portion of the sleeve; you could use<br />

the Charles of Blois’ multi-piece sleeve as a guide:<br />

38

Figure 7.70<br />

Image Copyright © I. Marc Carlson 1999<br />

Pourpoint of Charles of Blois, Duke of Brittany. It probably post-dates<br />

Charles’ death in 1364.<br />

However, I prefer the simpler 2-piece sleeve construction (a.k.a. a “coat” sleeve) which is<br />

seen in Elizabethan sources.<br />

Figure 7.71<br />

Ca. 1610 Sleeve of a Padded Doublet.<br />

From a garment construction point of view, I find it necessary to construct a full sleeve<br />

and then apply the puff on top of that. If you attach the lower sleeve directly to the sleeve<br />

39

puff, with nothing to stabilize the puff then the fullness gets pulled down and you only<br />

get a gathered section at the top of the sleeve but no poof adding width. You see this in<br />

the Italian fashions of the time, but the <strong>Burgundian</strong> fashions use the more aggressive poof<br />

as shown above.<br />

Doublet materials<br />

The artwork can’t say much about what the doublets were made of; other then they’re<br />

usually a solid color.<br />

“Jacqueline Herald cites that the outer fabric of Italian doublets could range from<br />

elegant fabrics such as silk brocades and velvet or to simple linen. Published<br />

information about the materials used to make doublets in Burgundy or France is<br />

limited. Margaret Scott notes that many doublets worn by the nobility in the<br />

1470s were made of silk or velvet, and there is also mention of fine worsted<br />

(wool) being used as well. Spanish doublets were made from silks, woolens or<br />

fustian (a linen-cotton blend). Although I could not find specific references to<br />

linen or linen-blend doublets in France or Burgundy, the presence of linen or<br />

linen-blend doublets in Spain and Italy, the close cultural ties that Spain had with<br />

Burgundy, and the ample availability of linen fabrics in France and Burgundy<br />

suggest that linen or linen-blend doublets were likely to have been made there.<br />

The only evidence I have found for English doublet materials were the wardrobe<br />

accounts for one year during the reign of Edward IV. The fabrics allotted for his<br />

doublets were generally silk satin or velvet for the outer layer and linen for<br />

linings. Allotments of fabrics for doublets for his family and servants included<br />

silks for the family and high-ranking officials and wool cloth for the lowerranking<br />

servants or servants involved with manual labor.” 5<br />

5<br />

http://www.nachtanz.org/SReed/doublets.html [Nov. 7, 2010] Susan Reed, “15th-Century Men’s<br />

Doublets: An Overview”<br />

40

Bibliography<br />

Arnold, Janet Patterns of Fashion. The cut and Construction of Clothes for Men and<br />

Women c1560-1620.New York: Macmillan, 1985.<br />

Batterberry, Michael and Ariane Batterberry. Fashion the Mirror of History.2 nd Edition.<br />

Hong Kong; Greenwich House, 1982.<br />

Blanc, Odile. Parades et Parures. L’invention du corps de mond à la fin du Moyen Age.<br />

Éditions Gallimard, 1997.<br />

Boucher, François. 20,000 Years of Fashion. The History of Costume and Personal<br />

Adornment. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.<br />

Carlson, I. Marc. Some Clothing of the Middle Ages. Historical Clothing from<br />

Archaeological Finds. http://www.personal.utulsa.edu/~marccarlson/cloth/bockhome.html<br />

[Nov. 7, 2010]<br />

Collins, Marie and Virginia Davis. A Medieval Book of Seasons. New York: Harper<br />

Collins Publishers, 1992.<br />

Dellaluna, Vangelista di Antonio. “How to Tie Bows”. http://www.florentinepersona.com/tying_bows.html<br />

[Nov. 7, 2010]<br />

Dunkerton, Jill, et al. Giotto to Dürer. Early Renaissance Painting in The National<br />

Gallery. London: National Gallery Publications Limited, 1991.<br />

Eustace, Emrys. “Shirts, Trewes, & Hose.i.: A Survey of Medieval Underwear”.<br />

http://www.greydragon.org/library/underwear1.html [Nov. 7, 2010]<br />

Eustace, Emrys. “Shirts, Trewes, & Hose.iii.: Chosen Hosen”.<br />

http://www.greydragon.org/library/underwear3.html [Nov. 7, 2010]<br />

Evans, Joan. Dress in Mediaeval France. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1952.<br />

Fox, Sally. The Medieval Woman an Illuminated Calendar 1997. New York: Workman<br />

Publishing, 1996.<br />

Frère, Jean-Claude. Early Flemish Painting. Trans. Peter Snowdon. Italy: The Art Book<br />

Subsidiary of Bayard Presse SA, 1997.<br />

Hallam, Elizabeth, ed. The Chronicles of the Wars of the Roses. Spain: CLB<br />

International, 1988.<br />

Jennings, Anne. Medieval Gardens. London: English Heritage and Museum of Garden<br />

History, 2004.<br />

41

Kemperdick, Stephan. Masters of Netherlandish Art. Rogier van der Weyden. Trans.<br />

Anthea Bell. Germany: Könemann Verlagsgsellschaft mbH, 1999.<br />

Payne, Blanche. History of Costume from the Ancient Egyptians to the Twentieth<br />

Century. New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 1965.<br />

Petrucci, Lorenzo. An Overview of Men’s Clothing in Northern Italy c. 1420-1480.<br />

www.houseofpung.net/sca/15c_mens_italian.pdf [Nov. 7, 2010]<br />

Reed, Susan. 15th-Century Men’s Doublets: An Overview<br />

http://www.nachtanz.org/SReed/doublets.html [Nov. 7, 2010]<br />

Scott, Margaret. The History of Dress Series. Late Gothic Europe, 1400-1500. Hong<br />

Kong: Publishers Mills & Boon Ltd, 1980.<br />

Scott, Margaret. Medieval Clothing and Costumes. Displaying Wealth and Class in<br />

Medieval Times. New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc., 2004.<br />

Scott, Margaret. Medieval Dress & Fashion. London: The British Library, 2007.<br />

Scott, Margaret. A Visual History of Costume. The Fourteenth & Fifteenth Centuries.<br />

London: B.T. Batsford Ltd., 1986.<br />

Tarrant, Naomi. The Development of Costume. 2 nd Edition. New York: Routledge, 1996.<br />

Unterkircher, F. King Rene’s Book of Love (Le Cueur d’Amours Espris). 3 rd Edition.<br />

Trans. Sophie Wilkins. New York: George Braziller, Inc. 1989.<br />

Voronova, Tamara and Andrei Sterligov. Western European Illuminated Manuscripts 8 th<br />

to 16 th Centuries. London: Sirrocco, 2006.<br />

Vos, Dirk de. Rogier van der Weyden. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Incorporated, 1999.<br />

Vos, Dirk de. Hans Memling. Ghent: Ludion Press, 1994.<br />

Table of Illustrations<br />

Frontspiece: Jennings 31.<br />

Figure 1.1: Durnkerton, et al. 15.<br />

Figure 2.1: Vos, Rogier van der Weyden 250.<br />

Figure 2.2: Voronova 119.<br />

Figure 2.3: Unterkircher f51v<br />

Figure 2.4: Batterberry 86.<br />

Figure 2.5: Payne 218.<br />

Figure 2.6: Batterberry, 89.<br />

Figure 3.1: Scott, Medieval Clothing and Costumes 27.<br />

42

Figure 4.1: I’ve lost the source<br />

Figure 4.2: Vos, Hans Memling 108.<br />

Figure 4.3: Vos, Hans Memling 108.<br />

Figure 4.4: Vos, Hans Memling 328.<br />

Figure 4.5: Vos, Hans Memling 269.<br />

Figure 4.6: Vos, Rogier van der Weyden 294.<br />

Figure 4.7: http://www.greydragon.org/library/underwear1.html [Nov. 7, 2010]<br />

Figure 4.8: Tarrant 53.<br />

Figure 4.9: Vos, Rogier van der Weyden 28.<br />

Figure 4.10: www.houseofpung.net/sca/15c_mens_italian.pdf [Nov. 7, 2010]<br />

Figure 5.1: I’ve lost the source<br />

Figure 5.2: Collins and Davis 28.<br />

Figure 5.3: Collins and Davis 58.<br />

Figure 5.4: http://gallica.bnf.fr/scripts/mediator.exe?F=C&L=08100103&I=000036 [Feb. 2008]<br />

Figure 5.5: Scott, Medieval Dress and Fashion 155.<br />

Figure 5.6: Vos, Hans Memling 32.<br />

Figure 5.7: Vos, Hans Memling 108.<br />

Figure 5.8: Kemperdick 11.<br />

Figure 5.9: Frère 107.<br />

Figure 5.10: Frère 107.<br />

Figure 5.11: http://gallica.bnf.fr/scripts/mediator.exe?F=C&L=08100103&I=000021 [Feb. 2008]<br />

Figure 5.12: I’ve lost the source<br />

Figure 5.13: Vos, Rogier van der Weyden 123.<br />

Figure 5.14: Collins and Davis 28.<br />

Figure 5.15: Voronova, 169.<br />

Figure 5.16: http://www.culture.gouv.fr/culture/medieval/en/b047.htm [Nov. 7, 2010]<br />

Figure 5.17: Frère 107.<br />

Figure 5.18: Vos, Rogier van der Weyden 250.<br />

Figure 5.19: Frère 8.<br />

Figure 5.20: Frère 89.<br />

Figure 5.21: http://www.wga.hu/art/m/memling/6copies/0149burg.jpg [Nov. 7, 2010]<br />

Figure 5.22: Durnkerton, et al. 97.<br />

Figure 5.23: http://www.medievalproductions.nl/compagnie_de_ordonnance/doubletpattern.html [Feb.<br />

2008]<br />

Figure 5.24: Kemperdick 64.<br />

Figure 5.25: http://www.personal.utulsa.edu/~marc-carlson/cloth/rogart.html [Nov. 7, 2010]<br />

Figure 5.26: Collins and Davis 58.<br />

Figure 5.27: I’ve lost the source<br />

Figure 5.28: I’ve lost the source<br />

Figure 5.29: Collins and Davis 28.<br />

Figure 5.30: http://gallica.bnf.fr/scripts/mediator.exe?F=C&L=08100104&I=000004 [Feb. 2008]<br />

Figure 5.31: http://www.personal.utulsa.edu/~marc-carlson/cloth/elizabeth.htm [Nov. 7, 2010]<br />

Figure 5.32: http://www.personal.utulsa.edu/~marc-carlson/cloth/arras.html [Nov. 7, 2010]<br />

Figure 5.33: www.houseofpung.net/sca/15c_mens_italian.pdf [Nov. 7, 2010]<br />

Figure 5.34: http://www.wga.hu/art/p/piero/2/7/7find07.jpg [Nov. 7, 2010]<br />

Figure 5.35: http://www.wga.hu/art/a/antonell/portra_m.jpg [Nov. 7, 2010]<br />

43

Figure 5.36: Vos, Hans Memling 191.<br />

Figure 5.37: Vos, Hans Memling 195.<br />

Figure 5.38: I’ve lost the source<br />

Figure 6.1: Batterberry 86.<br />

Figure 6.2: Evans, plate 37.<br />

Figure 6.3: Vos, Hans Memling 32.<br />

Figure 6.4: Scott, Medieval Dress and Fashion 155.<br />

Figure 6.5: I’ve lost the source<br />

Figure 6.6: Vos, Rogier van der Weyden 123.<br />

Figure 6.7: Vos, Hans Memling 106-7.<br />

Figure 6.8: Voronova 114.<br />

Figure 6.9: Hallam, 138.<br />

Figure 6.10: Vos, Hans Memling 32.<br />

Figure 6.11: Vos, Hans Memling 152.<br />

Figure 6.12: http://www.medievalproductions.nl/compagnie_de_ordonnance/doubletpattern.html [Feb.<br />

2008]<br />

Figure 6.13: Voronova 169.<br />

Figure 6.14: I’ve lost the source<br />

Figure 6.15: Scott, Late Gothic Europe 181.<br />

Figure 6.16: http://www.wga.hu/art/p/piero/2/8/8herac15.jpg [Nov. 2010]<br />

Figure 6.17: Vos, Hans Memling 32.<br />

Figure 6.18: http://www.medievalproductions.nl/compagnie_de_ordonnance/doubletpattern.html [Feb.<br />

2008]<br />

Figure 6.19: Voronova 169.<br />

Figure 6.20: Frère 107.<br />

Figure 6.21: http://gallica.bnf.fr/scripts/mediator.exe?F=C&L=08100062&I=000027 [Feb. 2008]<br />

Figure 6.22: http://www.culture.gouv.fr/culture/medieval/en/b047.htm [Nov. 7, 2010]<br />

Figure 6.23: Evans, plate 37.<br />

Figure 6.24: Scott, Medieval Dress and Fashion 155.<br />

Figure 6.25: Scott, Late Gothic Europe 181.<br />

Figure 6.26: Voronova 167.<br />

Figure 6.27: http://www.culture.gouv.fr/culture/medieval/en/b047.htm [Nov. 7, 2010]<br />

Figure 6.28: Fox, June.<br />

Figure 6.29: Frère 107.<br />

Figure 6.30: Voronova 167.<br />

Figure 6.31: Batterberry 86.<br />

Figure 6.32: Scott, Late Gothic Europe 181.<br />

Figure 6.33:<br />

http://www.medievalproductions.nl/compagnie_de_ordonnance/pictures/mansclothingback.jpg [Feb.<br />

2008]<br />

Figure 6.34: Vos, Rogier van der Weyden 250.<br />

Figure 6.35: Collins and Davis 58.<br />

Figure 6.36: Batterberry 86.<br />

Figure 6.37: Batterberry 86.<br />

Figure 6.38: I’ve lost the source<br />

Figure 6.39: http://gallica.bnf.fr/scripts/mediator.exe?F=C&L=08100062&I=000050 [Feb. 2008]<br />

Figure 6.40: Collins and Davis 36.<br />

44

Figure 6.41: Voronova 169.<br />

Figure 6.42: Scott, Late Gothic Europe 181.<br />

Figure 6.43: http://gallica.bnf.fr/scripts/mediator.exe?F=C&L=08100011&I=000013 [Feb. 2008]<br />

Figure 6.44: http://www.personal.utulsa.edu/~marc-carlson/cloth/london.html [Nov. 7, 2010]<br />

Figure 6.45: Scott, Late Gothic Europe 161.<br />

Figure 6.46: Vos, Rogier van der Weyden 123.<br />

Figure 6.47: Voronova 114.<br />

Figure 6.48: Hallam, 138.<br />

Figure 6.49: Vos, Hans Memling 106-7.<br />

Figure 6.50: Voronova 167.<br />

Figure 6.51: http://www.wga.hu/art/p/piero/2/3/3burial1.jpg [Nov. 7, 2010]<br />

Figure 7.1: Batterberry 86.<br />

Figure 7.2: http://www.culture.gouv.fr/culture/medieval/en/b047.htm [Nov. 7, 2010]<br />

Figure 7.3: Scott, Fourteenth & Fifteenth Centuries 99.<br />

Figure 7.4: Scott, Medieval Dress and Fashion 155.<br />

Figure 7.5: Collins and Davis 117.<br />

Figure 7.6: http://www.medievalproductions.nl/compagnie_de_ordonnance/pictures/mensdoublet.jpg<br />

[Feb. 2008]<br />

Figure 7.7: Frère 107.<br />

Figure 7.8: Vos, Hans Memling 152.<br />

Figure 7.9: I’ve lost the source<br />

Figure 7.10: Scott, Late Gothic Europe 161.<br />

Figure 7.11: Scott, Fourteenth & Fifteenth Centuries 100.<br />

Figure 7.12: Collins and Davis 58.<br />

Figure 7.13: Vos, Hans Memling 106-7.<br />

Figure 7.14: Scott, Medieval Dress and Fashion 155.<br />

Figure 7.15: Vos, Rogier van der Weyden 250.<br />

Figure 7.16: (Left) Vos, Hans Memling 269. (Right) Scott, Late Gothic Europe 161.<br />

Figure 7.17: Vos, Rogier van der Weyden 123.<br />

Figure 7.18: Vos, Hans Memling 32.<br />

Figure 7.19: Collins and Davis 58.<br />

Figure 7.20: Frère 107.<br />

Figure 7.21: Vos, Hans Memling 36.<br />

Figure 7.22: http://www.wga.hu/art/m/memling/6copies/0149burg.jpg [Nov. 7, 2010]<br />

Figure 7.23: Durnkerton, et al. 97.<br />

Figure 7.24: http://www.medievalproductions.nl/compagnie_de_ordonnance/doubletpattern.html [Feb.<br />

2008]<br />

Figure 5.25: Kemperdick 64.<br />

Figure 7.26: Scott, Late Gothic Europe 159.<br />

Figure 7.27: Collins and Davis 117.<br />

Figure 7.28: Blanc 6.<br />

Figure 7.29: Blanc 6.<br />

Figure 7.30: Batterberry 86.<br />

Figure 7.31: http://www.wga.hu/art/c/christus/2/grimston.jpg [Nov. 7, 2010]<br />

Figure 7.32: Scott, Late Gothic Europe 169.<br />

Figure 7.33: Scott, Fourteenth & Fifteenth Centuries 100.<br />

45

Figure 7.34: Payne 218.<br />

Figure 7.35: Payne 218.<br />

Figure 7.36: Fox, June.<br />

Figure 7.37: Batterberry 89.<br />

Figure 7.38: Evans, plate 37.<br />

Figure 7.39: Collins and Davis 117.<br />

Figure 7.40: Scott, Late Gothic Europe 161.<br />

Figure 7.41: Scott, Fourteenth & Fifteenth Centuries 99.<br />

Figure 7.42: Payne 218.<br />

Figure 7.43: Batterberry 86.<br />

Figure 7.44: Scott, Fourteenth & Fifteenth Centuries 99.<br />

Figure 7.45: Scott, Late Gothic Europe 159.<br />

Figure 7.46: Scott, Late Gothic Europe 169.<br />

Figure 7.47: Collins and Davis 117.<br />

Figure 7.48: Unterkircher f51v<br />

Figure 7.49: Evans, plate 37.<br />

Figure 7.50: Scott, Fourteenth & Fifteenth Centuries 99.<br />

Figure 7.51: Batterberry 86.<br />

Figure 7.52: Scott, Fourteenth & Fifteenth Centuries 99.<br />

Figure 7.53: Scott, Fourteenth & Fifteenth Centuries 100.<br />

Figure 7.54: Payne 218.<br />

Figure 7.55: Evans, plate 56.<br />

Figure 7.56: Scott, Late Gothic Europe 161.<br />

Figure 7.57: Vos, Hans Memling 281.<br />

Figure 7.58: Vos, Rogier van der Weyden 123.<br />

Figure 7.59: Vos, Rogier van der Weyden 102.<br />

Figure 7.60: Unterkircher f25v<br />

Figure 7.61: Unterkircher f31v<br />

Figure 7.62: Scott, Late Gothic Europe 178.<br />

Figure 7.63: Hallam, 27.<br />

Figure 7.64: http://www.medievalproductions.nl/compagnie_de_ordonnance/doubletpattern.html [Feb.<br />

2010]<br />

Figure 7.65: Evans, plate 60.<br />

Figure 7.66: Boucher 208.<br />

Figure 7.67: Scott, Medieval Dress and Fashion 155.<br />

Figure 7.68: Blanc 6.<br />

Figure 7.69: Scott, Late Gothic Europe 159.<br />

Figure 7.70: http://personal.utulsa.edu/~marc-carlson/cloth/blois.html [Nov. 7, 2010]<br />

Figure 7.71: Arnold 81.<br />

46