NC

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

By Gleb Raygorodetsky<br />

Photographs by Evgenia Arbugaeva<br />

Clad in a camouflage jacket, the mosquito<br />

netting unzipped from his<br />

hood, Yuri Khudi squats by the fire<br />

inside his large chum. Outside, seven<br />

more of the teepee-like tents cluster<br />

in a semicircle. Swells of Siberian tundra roll<br />

north toward the Arctic Ocean; a reindeer herd<br />

grazes on a distant crest. It’s mid-July, and the<br />

group of Nenets herders that Yuri leads are about<br />

halfway through an annual trek that takes them<br />

400 miles north on the Yamal Peninsula to the<br />

Arctic coast—in normal years, that is.<br />

“It’s been three years since we have made it all<br />

the way to our summer pastures by the Kara Sea,”<br />

Yuri says as his wife, Katya, pours him a steaming<br />

mug of tea. “Our reindeer were too weak for<br />

the long journey.” In the winter of 2013-14, an<br />

unusual warm spell brought rain to southern<br />

Yamal; the deep freeze that followed encased<br />

most of the winter pastures in thick ice. The reindeer,<br />

used to digging through snow to find lichen,<br />

their main winter food, couldn’t dig through the<br />

ice. In this herd and others, tens of thousands<br />

starved. Now, in the summer of 2016, the survivors<br />

are still recovering.<br />

The canvas entrance of the chum flaps open,<br />

and a reindeer, antlers down, bursts inside. It<br />

pauses in front of the fire, shakes vigorously, and<br />

flops down to chew its cud meditatively.<br />

“This young cow lost her mom, so we raised<br />

her ourselves inside the chum,” explains Yuri,<br />

taking a cautious sip of tea. “She doesn’t like<br />

mosquitoes. Hopefully next year she’ll have a calf<br />

of her own. We’re down to about 3,000 reindeer<br />

now, half of our usual herd.”<br />

The Nenets have undertaken this annual migration<br />

for centuries, and at 800 miles roundtrip,<br />

it’s one of the longest in the world. Yuri’s<br />

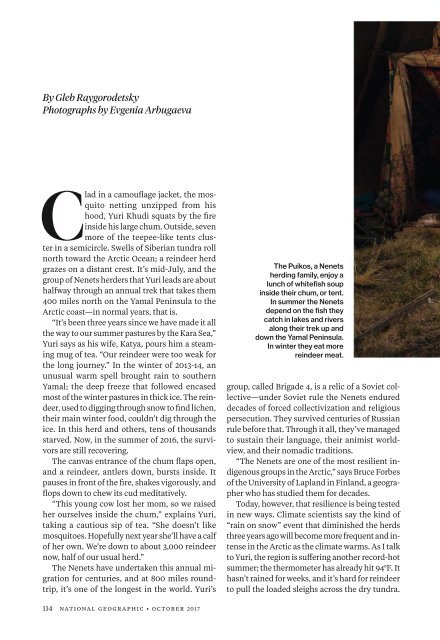

The Puikos, a Nenets<br />

herding family, enjoy a<br />

<br />

inside their chum, or tent.<br />

In summer the Nenets<br />

<br />

catch in lakes and rivers<br />

along their trek up and<br />

down the Yamal Peninsula.<br />

In winter they eat more<br />

reindeer meat.<br />

group, called Brigade 4, is a relic of a Soviet collective—under<br />

Soviet rule the Nenets endured<br />

decades of forced collectivization and religious<br />

persecution. They survived centuries of Russian<br />

rule before that. Through it all, they’ve managed<br />

to sustain their language, their animist worldview,<br />

and their nomadic traditions.<br />

“The Nenets are one of the most resilient indigenous<br />

groups in the Arctic,” says Bruce Forbes<br />

of the University of Lapland in Finland, a geographer<br />

who has studied them for decades.<br />

Today, however, that resilience is being tested<br />

in new ways. Climate scientists say the kind of<br />

“rain on snow” event that diminished the herds<br />

three years ago will become more frequent and intense<br />

in the Arctic as the climate warms. As I talk<br />

to Yuri, the region is suffering another record-hot<br />

summer; the thermometer has already hit 94°F. It<br />

hasn’t rained for weeks, and it’s hard for reindeer<br />

to pull the loaded sleighs across the dry tundra.<br />

114 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC • OCTOBER 2017