NC

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

| EXPLORE | ANIMALS<br />

BORN TO BE WILD<br />

By Jani Actman<br />

After videos of slow lorises (below)<br />

being tickled and fed rice balls in captivity<br />

swept the Internet, the wideeyed<br />

animals shot to viral fame. The<br />

YouTube videos generated thousands<br />

of comments about the primate’s adorable<br />

looks, but they also highlighted<br />

a grievous threat facing slow lorises:<br />

demand for them as pets.<br />

All species of slow lorises are supposed<br />

to be protected by local laws in<br />

southern Asia and by the Convention<br />

on International Trade in Endangered<br />

Species (CITES), a treaty that aims to<br />

prevent trade that could threaten wild<br />

species’ survival. Still, countless slow<br />

lorises are captured each year from their<br />

rain forest habitat and sold online, across<br />

borders, or to local wildlife markets.<br />

Customers find them irresistible, but<br />

these primates don’t fare well as pets. Before<br />

they’re sold, most undergo a painful<br />

process to remove their sharp teeth—and<br />

circumstances don’t improve from there.<br />

In a 2016 study, researchers from Oxford<br />

Brookes University examined a hundred<br />

online videos of pet lorises and concluded<br />

that all the animals were distressed,<br />

sick, or exposed to unnatural conditions.<br />

“They’re quite sensitive,” says Christine<br />

Rattel of International Animal Rescue,<br />

which runs a slow loris rescue program<br />

in Indonesia. “They are nocturnal, small<br />

animals that don’t like to be handled.”<br />

It’s uncertain how many slow lorises<br />

remain in the wild, but conservationists<br />

say populations have declined because<br />

the pet trade continues to run rampant.<br />

Habitat loss also has taken a toll, as has<br />

poaching for traditional Asian medicine,<br />

which ascribes therapeutic properties to<br />

the animals’ body parts. An ongoing pet<br />

trade “would really push lorises to the<br />

brink of extinction,” Rattel says.<br />

They’re hardly the only wildlife facing<br />

this threat. Cheetahs, lions, and<br />

other famed species end up in basements<br />

and backyards, as do lesser<br />

known creatures such as the ball python<br />

and long-tailed macaque.<br />

“The pet trade is probably one of the<br />

most devastating parts of the wildlife<br />

trade,” says wildlife-trafficking expert<br />

Chris Shepherd. But it’s “getting the least<br />

amount of attention.”<br />

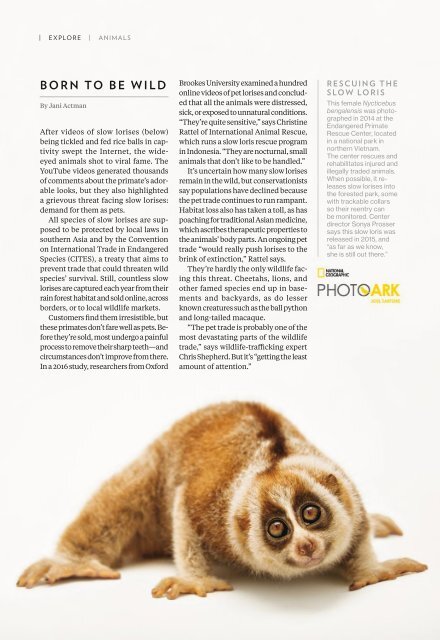

RESCUING THE<br />

SLOW LORIS<br />

This female Nycticebus<br />

bengalensis was photographed<br />

in 2014 at the<br />

Endangered Primate<br />

Rescue Center, located<br />

in a national park in<br />

northern Vietnam.<br />

The center rescues and<br />

rehabilitates injured and<br />

illegally traded animals.<br />

When possible, it releases<br />

slow lorises into<br />

the forested park, some<br />

with trackable collars<br />

so their reentry can<br />

be monitored. Center<br />

director Sonya Prosser<br />

says this slow loris was<br />

released in 2015, and<br />

“as far as we know,<br />

she is still out there.”