NC

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

that off. And if it can happen here, they say, it<br />

can happen anywhere.<br />

SHEIKH MOHAMMED GREW UP in a house lit by<br />

oil lamps, where water from the village well was<br />

delivered by donkey cart. The house belonged to<br />

his grandfather, the emir; the Al Maktoum family<br />

has ruled Dubai since 1833. The house still stands<br />

near the mouth of Dubai Creek, a natural harbor<br />

that is the reason the city exists at all. Sheikh<br />

Mohammed’s father, Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed Al<br />

Maktoum, had grown up in the same house and as<br />

a young man had endured years when people in<br />

Dubai starved; the Great Depression and the invention<br />

of cultured pearls had destroyed the market<br />

for pearl diving, the town’s main enterprise.<br />

It was Sheikh Rashid who began to modernize<br />

Dubai after taking over as ruler in 1958 and especially<br />

after oil started to flow in the late 1960s. He<br />

quickly brought in electricity, running water, and<br />

paved roads. He built schools, an airport, and, in<br />

1979, the 39-story World Trade Centre (now Sheikh<br />

Rashid Tower), at the time the tallest building in<br />

the Middle East. “It was built in the middle of nowhere,<br />

on the edge of the city,” says Neil Walmsley,<br />

a Dubai-based British engineer and urban planner<br />

with the consulting firm Arup. “The city responded<br />

by growing towards it”—and then well past it.<br />

The pearl business hadn’t lasted forever, and<br />

Sheikh Rashid knew the oil wouldn’t either.<br />

Dubai holds just a fraction of the U.A.E.’s oil—<br />

Abu Dhabi has the lion’s share. So while Dubai<br />

was not a center of world trade in 1979, when<br />

Sheikh Rashid built the Trade Centre, he set<br />

about making it one. That same year he opened a<br />

second and larger port at Jebel Ali, 25 miles from<br />

the Creek, as it’s known.<br />

His son Mohammed filled the empty space between<br />

the two, turning Dubai into a hub not only<br />

of trade and finance but also, improbably, of tourism<br />

and real estate development. Each Emirati<br />

citizen has long been entitled to a plot for his own<br />

villa. But in the early 2000s, when Dubai began<br />

allowing property to be owned by foreigners—<br />

already attracted by the lack of income taxes—<br />

cash flooded in. Four large developers carved up<br />

the land. Workers streamed in from South Asia<br />

to build villas and skyscrapers clad in glass—not<br />

the ideal material in a land of relentless sun, but<br />

what the market demanded. The workers lived<br />

in camps that were often squalid, in conditions<br />

that some said resembled indentured servitude.<br />

The city exploded down the coast. It spread<br />

out into the Persian Gulf, onto artificial peninsulas<br />

built from titanic amounts of dredged sand; it<br />

spread into the Arabian desert. “When you look<br />

at how Dubai has been growing, it’s just been this<br />

obsession with building outward into the desert,”<br />

says Yasser Elsheshtawy, an Egyptian-American<br />

architect who taught at U.A.E. University in Al<br />

Ain for 20 years. “There were no limitations.<br />

Energy was cheap. You had cars. So why not?”<br />

Sheikh Mohammed’s aspiration is like his<br />

father’s, only grander: He wants Dubai to outcompete<br />

the world, to show the world that Arabs<br />

can be pioneers again, as they were in the Middle<br />

Ages. His strategy has been to attract the world<br />

to Dubai. Some 90 percent of the 2.8 million residents<br />

are expats living in a place where not so<br />

long ago a few thousand Arabs struggled to survive.<br />

Dubai’s population, young and incr edibly<br />

diverse—children attend schools with dozens of<br />

nationalities, several expats told me proudly—<br />

is its main resource. But all those people have to<br />

be kept alive in the desert.<br />

These days Dubai has plenty of electricity<br />

and running water. Almost all of it comes from<br />

a single two-mile-long industrial plant at Jebel<br />

Ali. There, in a line of candy-striped smokestacks<br />

and evaporator tanks, the Dubai Electricity and<br />

Water Authority (DEWA) burns natural gas to<br />

generate 10 gigawatts of electricity. The leftover<br />

heat is used to desalinate seawater—more than<br />

500 million gallons a day. Gas comes by pipeline<br />

from Qatar, with which the U.A.E. severed diplomatic<br />

relations in June, and in tankers from as<br />

far away as the United States.<br />

Dubai, a tiny emirate we think of as oil rich,<br />

depends on imported fossil fuel for life support.<br />

One DEWA official, trying to convey to me<br />

how that feels, gripped his throat tightly with<br />

one hand. But there’s an upside to that choking<br />

feeling: It can motivate you to change your<br />

circumstances.<br />

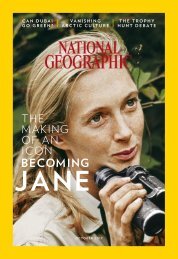

62 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC • OCTOBER 2017