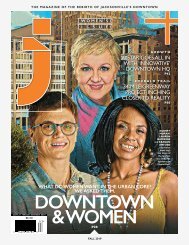

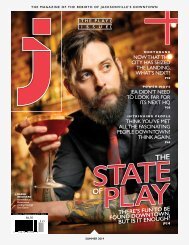

J Magazine Winter 2017

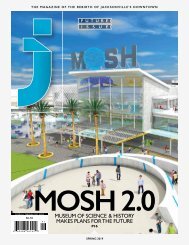

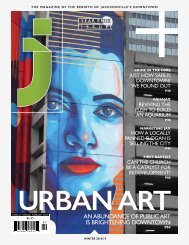

The magazine of the rebirth of Jacksonville's downtown

The magazine of the rebirth of Jacksonville's downtown

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Clara White Mission, FLORIDA TIMES-UNION ARCHIVES<br />

A curiosity hung in the house is a<br />

plaque with the bell from the yacht<br />

Magic, which won the America’s Cup in<br />

1870. Apparently it came off the Magic<br />

later when it was serviced in the Merrill<br />

shipyard.<br />

But the best single treasure in the<br />

house is a painting of a girls’ school<br />

in Aiken, S.C., that dates to 1845. It is<br />

attributed to miniaturist Henry Bounetheau<br />

or his wife, Julia Du Pré. The society<br />

says it was owned by their son, Henry<br />

Jr., who lived in Jacksonville and, during<br />

the Great Fire of 1901, was determined<br />

to save what he called his “mother’s<br />

painting.” The story is that he died in the<br />

rescue, but the painting survived — albeit<br />

with burn holes you can see today as it<br />

hangs in the Merrill House parlor.<br />

Clara White Museum<br />

The most personal, and perhaps<br />

touching, museum experience in<br />

Jacksonville may be a set of rooms on<br />

the second floor of the venerable Clara<br />

White Mission in LaVilla. The mission<br />

has its roots in the 1880s, when former<br />

slave Clara English White started helping<br />

feed her neighbors from her two-room<br />

house on Clay Street.<br />

She adopted Eartha, the secret child<br />

of a young wealthy white man and his<br />

family’s servant, and the remarkable<br />

mother-daughter team developed into<br />

what has been called the oldest humanitarian<br />

organization in Jacksonville and<br />

probably Florida.<br />

Author Tim Gilmore has written:<br />

“If the goodness, kindness, and mercy<br />

enacted in a particular building, on a<br />

certain quadrant of earth, can accrue<br />

across the years, then the Clara White<br />

Mission should be a pilgrimage site and<br />

613 Ashley Street in LaVilla is sacred<br />

ground.”<br />

Eartha White, who trained and toured<br />

as an opera singer in her youth, returned<br />

to Jacksonville in 1896 and became active<br />

in education, activism and business.<br />

But her lasting contribution was working<br />

with her mother, then alone, through<br />

the Clara White Mission and many other<br />

social-service projects and agencies,<br />

including founding what was then called<br />

the “Colored Old Folks Home,” now a<br />

nursing home.<br />

The work escalated greatly during the<br />

Great Depression, requiring more space,<br />

so Eartha White obtained the old Globe<br />

Theatre Building on Ashley and dedicated<br />

it to the memory of her mother. She<br />

never married and lived frugally in the<br />

second-floor rooms from 1932 until she<br />

died in 1974 at age 97. She lived in the<br />

middle of the swirling work providing<br />

food, housing and social services to the<br />

poor and homeless.<br />

Now those rooms are the Clara White<br />

Museum, which adds another poignant<br />

dimension to Jacksonville history.<br />

Eartha White’s bedroom barely holds<br />

her bed, dresser and a table. She saved<br />

the larger guest room for visiting friends,<br />

which the museum says included the<br />

Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Booker T.<br />

Washington, Mary McLeod Bethune,<br />

James Weldon Johnson and his brother<br />

John Rosamond Johnson, and Eleanor<br />

Roosevelt.<br />

The museum includes a parlor, a<br />

dining room and the kitchen, which prepared<br />

meals for the poor for more than<br />

40 years until a more modern one was<br />

added downstairs, now serving about<br />

400 meals a day in the mission, which<br />

includes 28 day beds.<br />

You might think the museum’s most<br />

treasured artifact is the organ donated by<br />

a member of Duke Ellington’s band. But<br />

CEO/President Ju’Coby Pittman says it’s<br />

Eartha White’s Bible because, before she<br />

would do business with visitors, she sat<br />

down and read the Bible with them.<br />

The building itself is historic. It began<br />

in 1907 as a hotel, then became a store<br />

and a gambling house before being<br />

turned into the Globe Theatre. The museum<br />

says Jacksonville’s premier architect<br />

Henry Klutho came from retirement<br />

to oversee the renovation of the building<br />

as a personal favor to Eartha White.<br />

If you want to be inspired through a<br />

visit, call the museum weekdays at (904)<br />

354-4162 and ask for Rosa Nicholas.<br />

You’ll have a chance to donate $5 for<br />

museum upkeep.<br />

TREASURES ON THE WAY<br />

Jacksonville Fire Museum<br />

Jacksonville has a very personal relationship<br />

with fire given that the Great Fire of<br />

1901 destroyed the heart of the city, burning<br />

146 city blocks across two miles, destroying<br />

more than 2,368 buildings and leaving<br />

almost 10,000 people homeless.<br />

Built largely with bricks salvaged from<br />

buildings razed by the fire, the Catherine<br />

Street Fire Station opened 10 months after<br />

the fire destroyed the original 1886 structure.<br />

It was the first all-black fire station, with an<br />

engine wagon and two horses on the first<br />

floor and the firefighters’ quarters on the<br />

second, connected by a traditional brass<br />

pole.<br />

The horses were retired as obsolete in<br />

1921, and the firefighting company left seven<br />

years later. The building was used as a repair<br />

shop and storage until it became the Jacksonville<br />

Fire Museum in 1982. It was moved<br />

from Catherine Street to Metropolitan Park<br />

on the riverfront in 1993. The museum was<br />

listed on the National Register of Historic<br />

Places in 1972 and included on the Florida<br />

Black Heritage Trail in 1992.<br />

But it’s not a museum right now. It quietly<br />

shut down in March 2016 after structural<br />

and water damage and lead paint were<br />

discovered. Officials say approximately<br />

$750,000 worth of repairs and restoration<br />

should be finished by April and the museum<br />

reopened by late next summer.<br />

What you’ll see, says the Jacksonville Fire<br />

and Rescue Department, is “an incredible<br />

variety of exhibits and artifacts that depict<br />

the evolution of our city’s fire service from its<br />

beginnings in the 1850s to the introduction<br />

of motorized vehicles in the 1920s, to the creation<br />

of our Rescue Division in the 1960s and<br />

CONTINUED ON PAGE 90<br />

WINTER <strong>2017</strong>-18 | J MAGAZINE 79