J Magazine Winter 2017

The magazine of the rebirth of Jacksonville's downtown

The magazine of the rebirth of Jacksonville's downtown

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

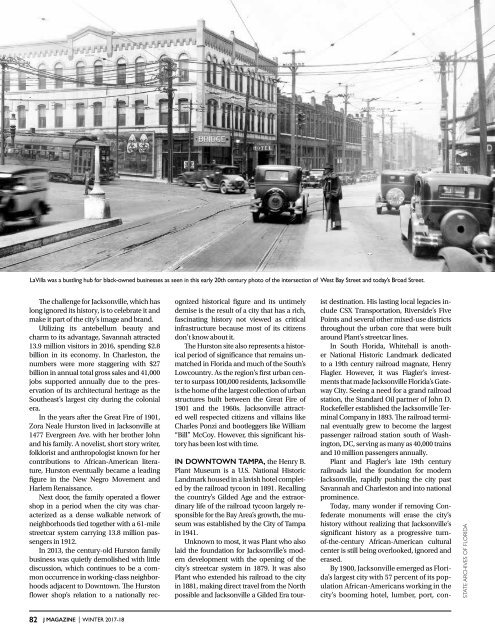

LaVilla was a bustling hub for black-owned businesses as seen in this early 20th century photo of the intersection of West Bay Street and today’s Broad Street.<br />

The challenge for Jacksonville, which has<br />

long ignored its history, is to celebrate it and<br />

make it part of the city’s image and brand.<br />

Utilizing its antebellum beauty and<br />

charm to its advantage, Savannah attracted<br />

13.9 million visitors in 2016, spending $2.8<br />

billion in its economy. In Charleston, the<br />

numbers were more staggering with $27<br />

billion in annual total gross sales and 41,000<br />

jobs supported annually due to the preservation<br />

of its architectural heritage as the<br />

Southeast’s largest city during the colonial<br />

era.<br />

In the years after the Great Fire of 1901,<br />

Zora Neale Hurston lived in Jacksonville at<br />

1477 Evergreen Ave. with her brother John<br />

and his family. A novelist, short story writer,<br />

folklorist and anthropologist known for her<br />

contributions to African-American literature,<br />

Hurston eventually became a leading<br />

figure in the New Negro Movement and<br />

Harlem Renaissance.<br />

Next door, the family operated a flower<br />

shop in a period when the city was characterized<br />

as a dense walkable network of<br />

neighborhoods tied together with a 61-mile<br />

streetcar system carrying 13.8 million passengers<br />

in 1912.<br />

In 2013, the century-old Hurston family<br />

business was quietly demolished with little<br />

discussion, which continues to be a common<br />

occurrence in working-class neighborhoods<br />

adjacent to Downtown. The Hurston<br />

flower shop’s relation to a nationally recognized<br />

historical figure and its untimely<br />

demise is the result of a city that has a rich,<br />

fascinating history not viewed as critical<br />

infrastructure because most of its citizens<br />

don’t know about it.<br />

The Hurston site also represents a historical<br />

period of significance that remains unmatched<br />

in Florida and much of the South’s<br />

Lowcountry. As the region’s first urban center<br />

to surpass 100,000 residents, Jacksonville<br />

is the home of the largest collection of urban<br />

structures built between the Great Fire of<br />

1901 and the 1960s. Jacksonville attracted<br />

well respected citizens and villains like<br />

Charles Ponzi and bootleggers like William<br />

“Bill” McCoy. However, this significant history<br />

has been lost with time.<br />

In Downtown Tampa, the Henry B.<br />

Plant Museum is a U.S. National Historic<br />

Landmark housed in a lavish hotel completed<br />

by the railroad tycoon in 1891. Recalling<br />

the country’s Gilded Age and the extraordinary<br />

life of the railroad tycoon largely responsible<br />

for the Bay Area’s growth, the museum<br />

was established by the City of Tampa<br />

in 1941.<br />

Unknown to most, it was Plant who also<br />

laid the foundation for Jacksonville’s modern<br />

development with the opening of the<br />

city’s streetcar system in 1879. It was also<br />

Plant who extended his railroad to the city<br />

in 1881, making direct travel from the North<br />

possible and Jacksonville a Gilded Era tourist<br />

destination. His lasting local legacies include<br />

CSX Transportation, Riverside’s Five<br />

Points and several other mixed-use districts<br />

throughout the urban core that were built<br />

around Plant’s streetcar lines.<br />

In South Florida, Whitehall is another<br />

National Historic Landmark dedicated<br />

to a 19th century railroad magnate, Henry<br />

Flagler. However, it was Flagler’s investments<br />

that made Jacksonville Florida’s Gateway<br />

City. Seeing a need for a grand railroad<br />

station, the Standard Oil partner of John D.<br />

Rockefeller established the Jacksonville Terminal<br />

Company in 1893. The railroad terminal<br />

eventually grew to become the largest<br />

passenger railroad station south of Washington,<br />

DC, serving as many as 40,000 trains<br />

and 10 million passengers annually.<br />

Plant and Flagler’s late 19th century<br />

railroads laid the foundation for modern<br />

Jacksonville, rapidly pushing the city past<br />

Savannah and Charleston and into national<br />

prominence.<br />

Today, many wonder if removing Confederate<br />

monuments will erase the city’s<br />

history without realizing that Jacksonville’s<br />

significant history as a progressive turnof-the-century<br />

African-American cultural<br />

center is still being overlooked, ignored and<br />

erased.<br />

By 1900, Jacksonville emerged as Florida’s<br />

largest city with 57 percent of its population<br />

African-Americans working in the<br />

city’s booming hotel, lumber, port, con-<br />

State Archives of Florida<br />

82 J MAGAZINE | WINTER <strong>2017</strong>-18