You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

DON’T WORK, MAKE MONEY<br />

with our democratic ideals, he just couldn’t cope and refused<br />

to continue his seminar. He retired soon after and died five<br />

months later. So in a way he was one of the victims of the<br />

whole movement. At one point my Doktormutter [doctoral<br />

supervisor] refused to speak to me for three months because<br />

I had voted along student lines and not with professors as a<br />

representative in the university governing body. Although I<br />

was her assistant! [Laughs]<br />

In <strong>May</strong> 1968 my wife and I were still in Berlin taking part in<br />

numerous demonstrations. However, that is the point when<br />

the Extra-parliamentary Opposition (APO) and the radicalisation<br />

began, which we thought was wrong. So we were happy<br />

to be able to get away to the States in August 1968. When<br />

I returned in 1970, everything had become very politicised.<br />

There were various factions competing against each other,<br />

fighting each other: the Albanian Maoists, the Trotskyists, the<br />

Chinese Maoists. In my view, it became more and more irrational.<br />

I increasingly distanced myself. It was endless fights<br />

among sectarian groups over leadership. In 1970, my professor<br />

told me she would offer me an assistantship. Then I got a<br />

telephone call: ‘This is Genosse [Comrade] Paul. We hear you<br />

are up for an assistantship. Would you be willing to present<br />

yourself to the student body?’ He invited me to a meeting on<br />

a Sunday night in a huge downtown Berlin apartment. It was<br />

arranged like a tribunal. There were four ‘comrades’ sitting<br />

in the front of the room. They interviewed the candidates for<br />

the research positions two at a time. The only question they<br />

were asked was, ‘In case of controversy between students<br />

and professors, who would you vote with?’ Of course both<br />

of them knew what they had to say. The first one said, ‘Of<br />

course with the students.’ But then he had second thoughts,<br />

and added something like, ‘Well, it would depend on the<br />

topic.’ That was the end of him. The other guy got the job.<br />

When I refused to take part in this tribunal, comrade Paul<br />

said ‘Then you’re not getting the job.’ [Luckily for Fluck it<br />

turned out his employment offer was connected to a special<br />

grant and was therefore exempt from the student veto over<br />

academic appointments. He could take up the job.]<br />

Looking back and despite the radical turn it later took, I<br />

believe that the student movement helped make the German<br />

university become a democratic place. Today’s students<br />

are still active in their own way: their political engagement<br />

has mostly shifted from class conflict to diversity issues.<br />

More importantly, the 1968 movement played a huge role in<br />

democratising Germany. When I grew up, Germany was still<br />

an authoritarian country in many ways. The next generation<br />

threw this overboard. I’d grown up as a German ashamed of<br />

Germany. When abroad and asked where I was from, I’d just<br />

say I was “European”. When I see the path of development<br />

Germany has since taken, I am mainly proud. — EJ<br />

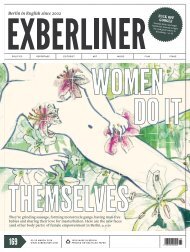

From Marxist to feminist<br />

Frigga Haug<br />

Born in 1937, Haug had already been an active Marxist<br />

militant for years when the 1968 student movement broke<br />

in Berlin. Converted to feminism after she experienced the<br />

‘trap’ of motherhood in a small town near Cologne, she ran<br />

back to Berlin and would soon dedicate her energy to the<br />

socialist women’s movement. At 80, Haug is one of Germany’s<br />

foremost feminist intellectuals and regularly speaks<br />

at conferences.<br />

I was in the SDS [Socialist German Student<br />

League] and co-founded the Marxist<br />

magazine Das Argument in 1959 [she’s<br />

still an editor for the publication to this<br />

day]. We covered all the topics of the time, which also<br />

became the questions of the 1968 movement: sexuality,<br />

author-ity and family, education, Poland, the war in<br />

Algeria, fascism, antisemitism, etc. At first, we thought<br />

the 1968ers’ demeanour wasn’t genuine politics – it<br />

was more like a disruption. We were working on analyses<br />

of capitalist society, but more and more people<br />

started going to big assemblies where everyone yelled<br />

over each other and whoever had charisma could take<br />

over. We were completely overwhelmed by the movement,<br />

but were also part of it. Das Argument became<br />

the mouthpiece of the 1968 movement. The print run<br />

jumped from 700 to 18,000.<br />

I was a Marxist before I was a feminist. But it was<br />

women from the SDS who were at the frontlines of<br />

the women's revolt. Media made it look like women<br />

in the SDS were limited to typing flyers and making<br />

coffee. That’s a total myth – I was in the SDS from the<br />

beginning and I never typed a flyer or made coffee.<br />

That said, women and women’s issues were never<br />

recognised as such in the movement and there was a<br />

grand total of seven women in SDS at the time. That’s<br />

when I joined the Action Committee for the Liberation<br />

of Women, which was<br />

just forming, in January or<br />

February 1968.<br />

“The men in the<br />

‘68 movement<br />

tolerated us...<br />

but the women’s<br />

movement was<br />

often called ‘petty<br />

bourgeois’ and<br />

'marginal'.”<br />

Women take action<br />

We questioned all the morals<br />

of the petty bourgeois:<br />

prudery, pettiness and<br />

taboos. We talked about the<br />

power of mass media. Axel<br />

Springer, the king of the Bild<br />

newspaper, was our enemy<br />

number one. We studied how<br />

the press creates submissive<br />

citizens. We believed that<br />

the situation of women was<br />

primarily a result of deficiencies<br />

in education, and we wanted to counter that with<br />

a a “political literacy” campaign. Our slogan from the<br />

socialist Frauenbund (women’s league) was: “Everyone<br />

should know everything!” I would say that men in the<br />

1968 movement tolerated us but didn’t actively support<br />

the women’s organisation. The women’s movement<br />

was often called “petty bourgeois” or “marginal” and<br />

not taken seriously.<br />

In Das Argument we had been studying Marx’s<br />

Grundrisse and Das Kapital, and I took that with me<br />

into the Action Committee. One wing of the movement<br />

wanted to organise a kindergarten teachers’<br />

strike. They believed that from an early age children<br />

were raised to be authoritarian personalities, so they<br />

needed an alternative perspective and way of life. But<br />

I had just escaped from a year trapped at home with<br />

a baby – I didn’t just want to talk about mothers and<br />

children. I wanted to study the big picture: How do<br />

women end up in a situation where, as soon as they<br />

MAY <strong>2018</strong><br />

9