You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

LEBENSKÜNSTLER<br />

Life after Tacheles:<br />

What’s become of<br />

the artist squatters?<br />

It was an artists’ utopia, a cultural<br />

institution, a tourist magnet: after<br />

over two decades on Oranienburger<br />

Straße, Tacheles was shut<br />

down, the artists kicked out. Five<br />

and a half years on, Taylor Lindsay<br />

tracked down the original clique to<br />

find out what came next.<br />

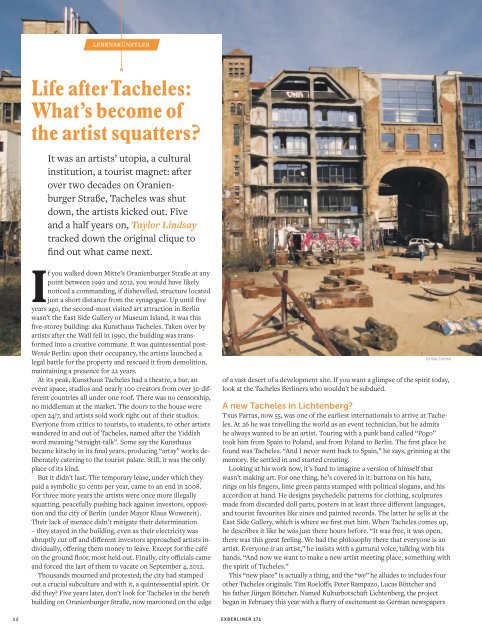

If you walked down Mitte’s Oranienburger Straße at any<br />

point between 1990 and 2012, you would have likely<br />

noticed a commanding, if dishevelled, structure located<br />

just a short distance from the synagogue. Up until five<br />

years ago, the second-most visited art attraction in Berlin<br />

wasn’t the East Side Gallery or Museum Island, it was this<br />

five-storey building: aka Kunsthaus Tacheles. Taken over by<br />

artists after the Wall fell in 1990, the building was transformed<br />

into a creative commune. It was quintessential post-<br />

Wende Berlin: upon their occupancy, the artists launched a<br />

legal battle for the property and rescued it from demolition,<br />

maintaining a presence for 22 years.<br />

At its peak, Kunsthaus Tacheles had a theatre, a bar, an<br />

event space, studios and nearly 100 creators from over 30 different<br />

countries all under one roof. There was no censorship,<br />

no middleman at the market. The doors to the house were<br />

open 24/7, and artists sold work right out of their studios.<br />

Everyone from critics to tourists, to students, to other artists<br />

wandered in and out of Tacheles, named after the Yiddish<br />

word meaning “straight-talk”. Some say the Kunsthaus<br />

became kitschy in its final years, producing “artsy” works deliberately<br />

catering to the tourist palate. Still, it was the only<br />

place of its kind.<br />

But it didn’t last. The temporary lease, under which they<br />

paid a symbolic 50 cents per year, came to an end in 2008.<br />

For three more years the artists were once more illegally<br />

squatting, peacefully pushing back against investors, opposition<br />

and the city of Berlin (under <strong>May</strong>or Klaus Wowereit).<br />

Their lack of menace didn’t mitigate their determination<br />

– they stayed in the building, even as their electricity was<br />

abruptly cut off and different investors approached artists individually,<br />

offering them money to leave. Except for the café<br />

on the ground floor, most held out. Finally, city officials came<br />

and forced the last of them to vacate on September 4, 2012.<br />

Thousands mourned and protested; the city had stamped<br />

out a crucial subculture and with it, a quintessential spirit. Or<br />

did they? Five years later, don’t look for Tacheles in the bereft<br />

building on Oranienburger Straße, now marooned on the edge<br />

Linda Cerna<br />

of a vast desert of a development site. If you want a glimpse of the spirit today,<br />

look at the Tacheles Berliners who wouldn’t be subdued.<br />

A new Tacheles in Lichtenberg?<br />

Txus Parras, now 55, was one of the earliest internationals to arrive at Tacheles.<br />

At 26 he was travelling the world as an event technician, but he admits<br />

he always wanted to be an artist. Touring with a punk band called “Pogo”<br />

took him from Spain to Poland, and from Poland to Berlin. The first place he<br />

found was Tacheles. “And I never went back to Spain,” he says, grinning at the<br />

memory. He settled in and started creating.<br />

Looking at his work now, it’s hard to imagine a version of himself that<br />

wasn’t making art. For one thing, he’s covered in it: buttons on his hats,<br />

rings on his fingers, lime green pants stamped with political slogans, and his<br />

accordion at hand. He designs psychedelic patterns for clothing, sculptures<br />

made from discarded doll parts, posters in at least three different languages,<br />

and tourist favourites like zines and painted records. The latter he sells at the<br />

East Side Gallery, which is where we first met him. When Tacheles comes up,<br />

he describes it like he was just there hours before. “It was free, it was open,<br />

there was this great feeling. We had the philosophy there that everyone is an<br />

artist. Everyone is an artist,” he insists with a guttural voice, talking with his<br />

hands. “And now we want to make a new artist meeting place, something with<br />

the spirit of Tacheles.”<br />

This “new place” is actually a thing, and the “we” he alludes to includes four<br />

other Tacheles originals: Tim Roeloffs, Peter Rampazo, Lucas Böttcher and<br />

his father Jürgen Böttcher. Named Kulturbotschaft Lichtenberg, the project<br />

began in February this year with a flurry of excitement as German newspapers<br />

12 EXBERLINER <strong>171</strong>