Historic Philadelphia

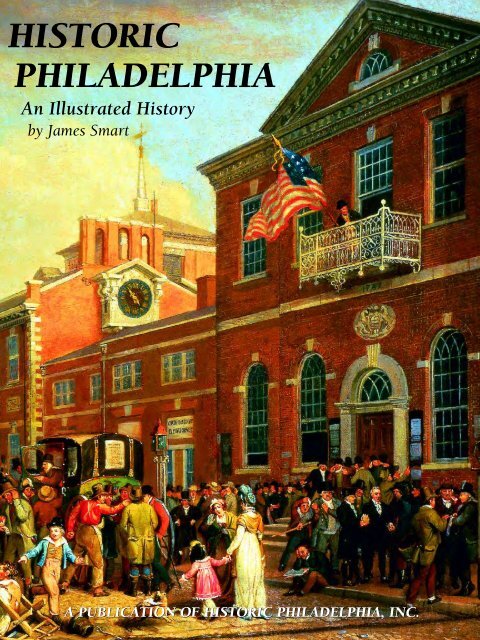

An illustrated history of the city of Philadelphia, paired with the histories of companies, families and organizations that make the region great.

An illustrated history of the city of Philadelphia, paired with the histories of companies, families and organizations that make the region great.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

HISTORIC<br />

PHILADELPHIA<br />

An Illustrated History<br />

by James Smart<br />

A PUBLICATION OF HISTORIC PHILADELPHIA, INC.

Thank you for your interest in this HPNbooks publication. For more information about other<br />

HPNbooks publications, or information about producing your own book with us, please visit www.hpnbooks.com.

HISTORIC<br />

PHILADELPHIA<br />

An Illustrated History<br />

by James Smart<br />

A publication of <strong>Historic</strong> <strong>Philadelphia</strong>, Inc.<br />

<strong>Historic</strong>al Publishing Network<br />

A division of Lammert Publications, Inc.<br />

San Antonio, Texas

✧<br />

With yellow fever ravaging <strong>Philadelphia</strong> in<br />

1793, President George Washington moved<br />

to the safer suburb of Germantown and<br />

occupied the Morris House, then about<br />

twenty years old, which General Sir<br />

William Howe had lived in after the Battle<br />

of Germantown. It was the president’s<br />

summer dwelling again in 1794.<br />

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR.<br />

First Edition<br />

Copyright © 2001 <strong>Historic</strong>al Publishing Network<br />

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical,<br />

including photocopying, without permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to<br />

<strong>Historic</strong>al Publishing Network, 8491 Leslie Road, San Antonio, Texas, 78254. Phone (210) 688-9006.<br />

ISBN: 1-893619-18-4<br />

Library of Congress Card Catalog Number: 2001088367<br />

<strong>Historic</strong> <strong>Philadelphia</strong>: An Illustrated History<br />

author: James Smart<br />

contributing writers for<br />

“sharing the heritage”: George Beetham<br />

Heather Harris<br />

Marie Beth Jones<br />

<strong>Historic</strong>al Publishing Network<br />

president: Ron Lammert<br />

vice president & project coordinator: Barry Black<br />

project representatives: Matthew J. DeJulio, Jr.<br />

Timothy B. Dorr<br />

John Lehman<br />

William E. Ruff<br />

director of operations: Charles A. Newton, III<br />

administration: Angela Lake<br />

Donna Mata<br />

Dee Steidle<br />

graphic production: Colin Hart<br />

John Barr<br />

PRINTED IN SINGAPORE<br />

HISTORIC PHILADELPHIA<br />

2

CONTENTS<br />

4 FOREWORD<br />

5 INTRODUCTION<br />

“Here is Enough”<br />

6 PROLOGUE<br />

Before There Was A City<br />

the Lenni Lenape<br />

the explorers<br />

the Dutch<br />

the Swedes<br />

trouble on the river<br />

Dutch again<br />

and finally, English<br />

10 CHAPTER I<br />

William Penn’s City<br />

young William Penn<br />

founding a City<br />

building a city<br />

Governor Penn arrives<br />

land deals & great promises<br />

back in England<br />

trouble in Pennsylvania<br />

final farewells<br />

the city’s early years<br />

22 CHAPTER II<br />

Ben Franklin’s City<br />

the kid from Boston<br />

building a state house<br />

politics & play-acting<br />

a bell & other improvements<br />

trouble with taxes<br />

the declaration<br />

the British take over<br />

the convention city<br />

changing into the capital<br />

yellow fever<br />

46 CHAPTER III<br />

The Quaker City<br />

capital of a nation<br />

race, religion & politics<br />

life in the capital<br />

commerce & culture<br />

Strickland does Philly<br />

railroads & riots<br />

the turbulent Forties<br />

the Quaker city<br />

70 CHAPTER IV<br />

The Centennial City<br />

consolidation<br />

war years<br />

peace & progress<br />

centennial time<br />

the great exhibition<br />

the city at 200<br />

90 CHAPTER V<br />

The Corrupt & Contented City<br />

the Nineties<br />

the century turns<br />

corrupt & contented<br />

war & hoagies<br />

the Twenties<br />

the soggy sesqui<br />

the radio city<br />

the Depression years<br />

110 CHAPTER VI<br />

The Bicentennial City<br />

war and party conventions<br />

city hall scandals<br />

democrats take over<br />

restless decade<br />

the bicentennial<br />

124 CHAPTER VII<br />

The 300-Year-Old City<br />

the Eighties<br />

the century ends<br />

130 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS<br />

132 SHARING THE HERITAGE<br />

190 INDEX<br />

192 SPONSORS<br />

CONTENTS<br />

3

FOREWORD<br />

INTO THE TREES<br />

This book is not a scholarly work. Readers seeking comprehensive details, weighty analysis, or<br />

footnotes will have to look elsewhere. Its goal is to amble pleasantly through nearly four centuries<br />

of <strong>Philadelphia</strong> history, stopping here and there along the way to examine interesting people,<br />

events, buildings, and activities. It is anecdotal, episodic, possibly even erratic. Recording every<br />

worthwhile event and person would require a bookshelf, not a mere book. If some major items are<br />

ignored while trivial ones are emphasized, relax. History is more fun that way.<br />

In that spirit, the author assumes the customary responsibility for errors, and apologizes for<br />

omissions both accidental and intentional.<br />

Struthers Burt, in his 1945 book about the city, wrote: “<strong>Philadelphia</strong> is a fascinating place and<br />

one of the hardest subjects imaginable to write about. The trees are so thick, the little wandering<br />

forest byways and paths so numerous and so interesting, that it is almost impossible at times to see<br />

the forest.”<br />

Follow me into the trees.<br />

✧<br />

This 1839 Massachusetts abolitionist<br />

pamphlet first applied the name Liberty Bell<br />

to <strong>Philadelphia</strong>’s nearly forgotten State<br />

House bell, starting it on the way to being a<br />

national icon.<br />

COURTESY OF A PRIVATE COLLECTION.<br />

HISTORIC PHILADELPHIA<br />

4

INTRODUCTION<br />

“ HERE IS ENOUGH”<br />

“I doe Call the Citty to be layd out by the Name of <strong>Philadelphia</strong> and soe I will have it Called.”<br />

William Penn wrote that instruction on October 28, 1681, in a memo from London to his<br />

cousin, William Markham, his deputy governor in his new province of Pennsylvania.<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong> was the name of an ancient city that Christians since New Testament times had<br />

admired for its faithfulness. The Greek word is usually defined as “City of Brotherly Love.” Penn<br />

didn’t say what he thought it meant, but Thomas Blount’s Glossographia, a dictionary published in<br />

1656, said it “signifies brotherly or sisterly love.”<br />

The city that Penn and his helpers “layd out” has spread from two square miles to 135, and there<br />

are, at the moment, about a million and a half more residents than Penn ever saw. Through more<br />

than three centuries, his city has endured epidemics, military occupation, race and religious riots,<br />

economic depressions, political scandals, a Super Bowl loss, and other municipal catastrophes.<br />

His city has also enjoyed moments of glory. It produced the documents that created our nation.<br />

It gave America its first stock exchange, zoo, hospital, bank, abolition society, trade union, and ice<br />

boat. It has given the world a superior symphony orchestra, a glorious annual flower show, the first<br />

electronic computer, South Street and Manayunk nightlife, the oldest continuously functioning<br />

theater in the English speaking world, the revolving door, bubble gum, and hoagies.<br />

People of many races, nationalities, skills, ideas, and dreams became <strong>Philadelphia</strong>ns through the<br />

generations. Their experiences created the city, with its imperfections and its delights.<br />

“Here is enough for both poor & rich, not only for necessity but pleasure,” William Penn wrote<br />

of his city three centuries ago. For most <strong>Philadelphia</strong>ns, that remained true through all the years.<br />

This book tries to tell their story.<br />

✧<br />

Thomas Blount’s Glossographia Anglicana<br />

Nova, or A Dictionary Interpreting Such<br />

Hard Words of Whatsoever Language as<br />

Are Presently Used, was first published in<br />

1656, when William Penn was a twelveyear-old<br />

pupil at Chigwell Free Grammar<br />

School in Wanstead, Essex, six miles east of<br />

London. Perhaps young Penn read in it that<br />

the name “<strong>Philadelphia</strong>” signifies brotherly<br />

or sisterly love.<br />

COURTESY OF RARE BOOK DEPARTMENT,<br />

FREE LIBRARY OF PHILADELPHIA.<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

5

HISTORIC PHILADELPHIA<br />

6

PROLOGUE<br />

BEFORE THERE WAS A CITY<br />

THE LENNI LENAPE<br />

“Wapsiypayat.” The White, he comes.<br />

That word, recorded in the Walam Olum, the sacred writings of the Lenni Lenape, announced the<br />

ultimate doom of the Native Americans who lived on the banks of the Delaware River, where one<br />

day <strong>Philadelphia</strong> would be built.<br />

They were an old, proud nation. They believed that God had created them first upon the earth.<br />

Their very name, Lenni Lenape, means “the original people.” In ancient times, they had conquered<br />

this continent. The Europeans would take it away from them.<br />

THE<br />

EXPLORERS<br />

Englishman Henry Hudson, probing for a shortcut to India on behalf of Dutch merchants,<br />

poked briefly into Delaware Bay on August 28, 1609. He thought it was too shallow for his ship,<br />

and pushed north to discover the river that later was given his name. To the Dutch in 1609, the<br />

Hudson was the North River, the Delaware the South River.<br />

In 1610, a ship commanded by Sir Samuel Argall, an Englishman, wandered into the South River.<br />

Thomas West, governor of the three-year-old colony at Jamestown, Virginia, had sent Argall to Bermuda<br />

to buy hogs. Instead, Sir Samuel went to New England and bought fish. His reasons for the detour are<br />

unknown, but on his way home, he did some sightseeing on the river. He decided that it should be<br />

named to honor Sir Thomas, whose title was Baron de la Ware, and the Delaware River it became.<br />

THE<br />

DUTCH<br />

Captain Cornelis Jacobsen Mey showed up in 1614, named one shore of the bay Cape May after<br />

himself, and claimed the river for the Dutch. In 1623, Mey returned, on a ship called New<br />

Netherlands, with thirty families to be the first settlers. Most of the colonists went to the North<br />

River, but four married couples and some military men came to the Delaware.<br />

Captain Mey took the families to an island far up the river, where they built a brick house. The<br />

soldiers and sailors erected a log fort on the east bank of the river, opposite the mouth of the<br />

Schuylkill ( Dutch for “hidden river.”) These were the first Europeans to live in the Delaware Valley.<br />

It’s not known how long they stayed or why they left.<br />

The Dutch made another attempt to colonize the area in 1631, this time down on the bay, near<br />

the present Lewes, Delaware. They insulted the local Lenni Lenape, who destroyed the colony. In<br />

1632, Dutch colonization of the Delaware Valley was suspended.<br />

✧<br />

This fragment of a map of the Delaware<br />

River, drawn in 1655 by Peter Lindstrom,<br />

royal Swedish engineer, shows early<br />

European spellings of Native American<br />

place names familiar today: Passayung,<br />

Meneyackse (Manayunk), Kackamensi<br />

(Shackamaxon), Penipackakyl (Pennypack),<br />

and Poaetguessingh (Poquessing.) With<br />

letters and numbers, Lindstrom also<br />

footnoted such enduring names as<br />

Tinnaconck (Tinicum) and Kinsessing.<br />

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR.<br />

THE<br />

SWEDES<br />

Several Dutchmen still wanted to establish a presence on the Delaware, including Peter Minuit,<br />

who had been fired after six years as governor of the Dutch settlement on Manhattan Island. They<br />

applied to King Adolphus Gustavus of Sweden, who was killed in battle in 1632. His daughter,<br />

Christina, became queen at age six. Her adult advisers granted the Dutch adventurers twenty years<br />

exclusive trading rights on the Delaware River.<br />

The new company raised funds to outfit two ships, which arrived on the Delaware in March<br />

1638. In July a load of furs purchased from the Indians was shipped home. Their sale brought<br />

PROLOGUE<br />

7

✧<br />

Top, left: A Lenni Lenape native family was<br />

depicted in a seventeenth century Swedish<br />

book about settlements in the Delaware<br />

River Valley.<br />

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR.<br />

Top, right: Thomas West, Lord de la Ware,<br />

was honored in 1610 by having a river<br />

named for him.<br />

COURTESY OF THE AMERICAN DICTIONARY OF PORTRAITS.<br />

Below: Johan Bjornsson Printz governed<br />

New Sweden on the Delaware with a tough<br />

attitude, backed up by a four-hundredpound<br />

physique.<br />

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR.<br />

HISTORIC PHILADELPHIA<br />

8<br />

14,500 florins, and the expedition had cost<br />

46,000 florins thus far. The investors in<br />

Sweden were unhappy, but the settlers on the<br />

Delaware were prospering. They built a fort at<br />

the present location of Wilmington and<br />

named it Christina. With the colonists was<br />

Anthony, a slave from Angola, certainly the<br />

first African resident of the Delaware Valley.<br />

TROUBLE ON THE RIVER<br />

In 1640, an Englishmen, George<br />

Lamberton, bought land from the Indians on<br />

the east bank of the Schuylkill. He was the<br />

first European to settle within the modern<br />

boundaries of <strong>Philadelphia</strong>.<br />

The Swedish government appointed<br />

a tough new governor for New Sweden: Johan<br />

Bjornsson Printz, a cavalry veteran of the<br />

perpetual European wars. He weighed four<br />

hundred pounds, ate constantly, and drank<br />

half pints of buckshot when he needed<br />

a laxative. The Indians nicknamed him<br />

“Big Belly.”<br />

Printz erected an eight-cannon fort across<br />

the river from the English claim, and fortified<br />

swampy Tinicum Island (just below the<br />

present site of <strong>Philadelphia</strong> International<br />

Airport), controlling river access to<br />

Lamberton’s homestead. He invited<br />

Lamberton to come down the river and<br />

discuss the situation. Lamberton and two<br />

followers paid the visit, and were instantly<br />

put in chains and forced to take a loyalty oath<br />

to Sweden. Big Belly built several other forts,<br />

including a block house on the site of the<br />

present Gloria Dei Church in South<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong>. “Send me 200 soldiers,” Printz<br />

said in a dispatch to Sweden, “and I’ll break<br />

the necks of everybody on the river.”

DUTCH<br />

AGAIN<br />

The Dutch just wouldn’t quit. In 1655 a fleet<br />

of five Dutch ships sailed up the Delaware, commanded<br />

by Peter Stuyvesant, the one-legged soldier<br />

who was governing New Netherlands from<br />

his Manhattan base. The 368 Swedish settlers<br />

were outnumbered, the Swedish government<br />

had lost interest, and so the names of all the forts<br />

and towns changed from Swedish to Dutch.<br />

AND<br />

FINALLY, ENGLISH<br />

In 1664 King Charles II of England gave his<br />

brother James, Duke of York, title to everything<br />

from New England to the Delaware Bay.<br />

Stuyvesant and his followers weren’t strong<br />

enough to resist the British fleet that arrived<br />

off Manhattan. So, New Amsterdam was converted<br />

to New York and the Delaware Valley<br />

became British.<br />

✧<br />

Christina became queen of Sweden at age six<br />

in 1632. Regents advised her to commission<br />

Swedish traders to settle the Delaware Valley.<br />

The young queen enjoyed riding, hunting,<br />

shooting and swearing, and reviewed her<br />

troops on horseback while twirling an<br />

imaginary mustache. She also learned six<br />

languages before she was eighteen.<br />

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR.<br />

PROLOGUE<br />

9

HISTORIC PHILADELPHIA<br />

10

WILLIAM PENN’S CITY<br />

YOUNG WILLIAM PENN<br />

William Penn was born in London in 1644. His father, at age twenty-three, had just been<br />

appointed an admiral of the British navy. Before Penn’s first birthday, a Puritan army captain named<br />

Oliver Cromwell led a defeat of the king’s army. By 1649 King Charles I was beheaded and<br />

Cromwell was dictator of England.<br />

Admiral Penn served both Charles and Cromwell with equal loyalty. Cromwell rewarded him with<br />

estates in Ireland. It was at one of them, Macroom, a fifteenth century castle near Cork, that fourteenyear-old<br />

William Penn’s future was influenced when he heard a Quaker preacher named Thomas Loe.<br />

After Cromwell died in 1658, the quarreling British factions came to terms. The son of Charles<br />

I, exiled in France, was invited to occupy the English throne. Admiral Penn was commissioned to<br />

sail across the channel and bring back Charles II. William, fifteen, went along on the trip.<br />

William Penn entered Oxford University in 1660, but was thrown out in 1662. His father gave<br />

him a thrashing, but Penn couldn’t care less. Oxford, he snarled, was “a signal place for idleness,<br />

loose living, profaneness, prodigality and gross ignorance.”<br />

Sent to Ireland to collect rents from the family estates in 1666, Penn again encountered Thomas<br />

Loe. His developing religious opinions and his dissatisfaction with the royal Church of England fell<br />

together. He joined the semi-outlawed Society of Friends, and became an active Quaker preacher<br />

and writer. In December of 1668, one of his books drew a blasphemy charge. He was locked in an<br />

unheated cell in the Tower of London, underfed and allowed no visitors unless he renounced his<br />

religious opinions. His father pulled some strings and got him released in July. When he emerged,<br />

twenty-four-year-old Penn had lost most of his hair. For the rest of his life, he wore wigs. “He wares<br />

them to keep his head & ears warm & not for pride,” a Quaker friend wrote.<br />

Visiting some fellow Quakers, Penn met Gulielma Springett, a pretty Quaker his age who had<br />

inherited an income from real estate of ten thousand pounds a year, about five times the Penn family<br />

income and perhaps one hundred times the average London tradesman’s wage. They became engaged.<br />

Penn’s increasing Quaker activities guaranteed that he would pass a lot of time in jail. He spent<br />

a month in the Tower in 1670. Ten days after he got out, his father died. The admiral was forty-nine.<br />

Within two weeks of his father’s funeral, Penn was arrested for illegal preaching and sent to Newgate<br />

prison for six months. He refused his gentleman’s privilege of renting a decent room in the fourhundred-year-old<br />

prison, but stayed in the Common Room where thieves, prostitutes, and other<br />

offenders were thrown together without regard to age, sex or health. While there, Penn wrote<br />

religious pamphlets, letters, and poetry.<br />

After his release, he married Gulielma. And he got an appointment that changed his life. He was<br />

chosen to arbitrate a dispute among four Quaker businessmen over a land grant in North America,<br />

a place named New Jersey. Penn assumed control of part of New Jersey, and was able to send a<br />

group of Quaker colonists to settle at Burlington in 1677.<br />

The episode gave William Penn an idea. If he could get clear ownership of some land in North<br />

America, he might found a colony governed on Quaker principles. And nobody was doing much<br />

with the wilderness right across the Delaware River from New Jersey.<br />

On June 1, 1680, Penn petitioned King Charles II for all the land west of the Delaware, extending<br />

north from the border of Maryland for five degrees of latitude.<br />

✧<br />

Benjamin West, a <strong>Philadelphia</strong>n who went<br />

to England and became the favorite court<br />

painter of King George III, was<br />

commissioned by the Penn family in 1773 to<br />

paint William Penn’s legendary treaty with<br />

the Indians a century earlier. West’s<br />

conjectural depiction of an improbably<br />

overweight Penn offering some yard goods<br />

to the Lenape sachems is an image fixed<br />

indelibly in the <strong>Philadelphia</strong> psyche.<br />

COURTESY OF THE PENNSYLVANIA ACADEMY OF THE FINE<br />

ARTS, PHILADELPHIA. GIFT OF MRS. SARAH HARRISON<br />

(THE JOSEPH HARRISON, JR. COLLECTION).<br />

FOUNDING A CITY<br />

Charles II was six-foot-three, a near giant by seventeenth century standards. He was a highliving<br />

spendthrift who loved tennis and women. He had thirteen mistresses at one time or another,<br />

CHAPTER I<br />

11

✧<br />

Right: The bust carved nine years after<br />

William Penn’s death by Sylvanus Bevan, a<br />

London apothecary who knew Penn, may be<br />

the best likeness among the rare portraits of<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong>’s founder. Ben Franklin and<br />

eighteenth century historian Robert Proud<br />

both reported that friends of Penn praised<br />

its accuracy.<br />

COURTESY OF THE CITY OF PHILADELPHIA,<br />

DEPARTMENT OF RECORDS, CITY ARCHIVES.<br />

Below: The ruins of Macroom Castle,<br />

twenty-six miles west of Cork in Ireland,<br />

where a wandering Quaker preacher gave<br />

fourteen-year-old William Penn his first<br />

exposure to the new religious ideas of the<br />

Society of Friends. Oliver Cromwell had<br />

presented the Macroom estate, with its<br />

three-story fifteenth century castle, to<br />

Penn’s father when he retired as an admiral<br />

in 1656.<br />

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR AND<br />

THE IRISH TOURIST BOARD.<br />

and twelve illegitimate children by seven<br />

different women. He was probably pleased<br />

when William Penn requested land for a<br />

Quaker colony. Maybe those nuisance<br />

Quakers would all move out and leave the<br />

Church of England in peace.<br />

Also, he owed Penn money. Penn’s father<br />

once paid for rations for the Royal Navy out of<br />

his own pocket, when the crown was short on<br />

funds. The debt came to about sixteen<br />

thousand pounds. King Charles was surely<br />

happy that Penn would take land instead<br />

of cash.<br />

On March 4, 1681, Charles II signed<br />

documents giving William Penn forty-five<br />

thousand square miles, their boundaries illdefined.<br />

It was the largest tract of land ever<br />

owned by a private citizen.<br />

Penn set up a real estate sales operation<br />

immediately. His lawyer’s clerks began<br />

drawing up batches of deeds with blanks left<br />

for name, price and number of acres. He had<br />

agents peddling Pennsylvania land in Ireland,<br />

Scotland, Wales, Holland, and Germany.<br />

There were thirty-four sales the first week,<br />

471 by the end of the year.<br />

Penn offered a variety of lot sizes and<br />

payment plans. Buyers of large acreage in the<br />

country were offered bonuses of city lots on<br />

which to build a town house. City purchasers<br />

could get a bonus of liberty land (we would<br />

probably call it free land) in areas just outside<br />

the city; the Northern Liberties ultimately<br />

became the most built-up, and the name<br />

survives as a neighborhood just north of the<br />

original city limits.<br />

A group of “adventurers” (we would say<br />

investors) could buy fifty thousand acres and<br />

operate it under the feudal concept of “manor<br />

of frank.” The group could charter towns, levy<br />

its own taxes, resell land and use natural<br />

resources. This deal brought in a London<br />

investment group called the Free Society of<br />

Traders. Among its holdings was all the land<br />

between Spruce and Pine Streets from river to<br />

river. The hill at the east end of the Society’s<br />

tract became known as Society Hill.<br />

BUILDING A CITY<br />

While William Penn stayed home,<br />

drumming up customers, his cousin, William<br />

Markham, sailed for Pennsylvania to act as<br />

Penn’s deputy governor. With the help of two<br />

men already living along the Delaware,<br />

Thomas Fairman and Lasse Cock, Markham<br />

began inspecting land and measuring the<br />

HISTORIC PHILADELPHIA<br />

12

iver, looking for the best spot to build<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong>. Fairman was a British Quaker<br />

who already had built a riverside brick house<br />

at Shackamaxon. Cock was a Swedish settler<br />

who spoke English and Lenni Lenape.<br />

Markham found villages at New Castle<br />

(Penn’s grant included what is now Delaware),<br />

Upland (now Chester), on Tinicum Island, on<br />

the banks of the Schuylkill and at Kingsessing<br />

and Passayunk. There were Swedish waterpowered<br />

mills on several creeks, and Swedish<br />

farmland under cultivation. The three<br />

Swanson brothers were using much of the<br />

land along the Delaware just above the<br />

Schuylkill, at the place called Wicaco. They<br />

had been farming there for nearly forty years.<br />

Hannah Salter, a Quaker widow, owned<br />

most of the riverfront land between the<br />

Swanson tract and Fairman’s. The Indians<br />

called the area Coaquannock. It means “pine<br />

tree place.”<br />

Elizabeth Kinsey, before she married<br />

Fairman, had bought Shackamaxon from Lasse<br />

Cock in 1678. The Cock family and other<br />

Swedes were using the land from Shackamaxon<br />

up to a creek called the Quessinawomink<br />

(today spelled Wissinoming.)<br />

Markham had his eye on Swanson<br />

territory, because he wanted to establish the<br />

new city at the best site for a harbor. The cove<br />

of Dock Creek created a natural landing place<br />

for waterborne arrivals. There was a sandy<br />

beach, with pine trees overhanging a high<br />

bank. The Swanson brothers agreed to swap<br />

the northern part of their claim (now covered<br />

by Society Hill and Old City) in exchange for<br />

equal land on the west bank of the Schuylkill.<br />

In October of 1681, a ship called Bristol<br />

Factor sailed with the first load of Penn’s<br />

purchasers, sixteen adults and some children.<br />

Bristol Factor arrived on December 15, got<br />

frozen in the ice on the river at Upland, and<br />

had to stay there all winter. The ships John &<br />

Sarah and Amity also sailed in 1681. By the<br />

end of 1682, there would be twenty-three<br />

shiploads of settlers. “Blessed be the Lord that<br />

of 23 ships, none miscarried,” Penn wrote.<br />

“Only two or three had smallpox.”<br />

On the John & Sarah was William Crispin,<br />

carrying instructions from William Penn on<br />

how to lay out the city. Crispin died on the<br />

voyage. Thomas Holme, appointed by Penn to<br />

survey the new city, didn’t arrive until August<br />

1682. Six other ships arrived that August.<br />

Edward Jones, one of the first Welsh<br />

immigrants, wrote home that he found “a<br />

crowd of people striving for ye country land,<br />

for ye town lot is not divided.”<br />

Holme had drawn a careful plan of the city,<br />

but people can’t live on a map. Some dug caves<br />

✧<br />

Thomas Holme’s 1682 plan for the city, as<br />

he explained it, consisted of “a large Frontstreet<br />

to each river, and a High-street (near<br />

the middle) from Front (or river) to Front,<br />

of one hundred foot broad, and a Broadstreet<br />

in the middle of the city, from side to<br />

side, of the like breadth.” Later, the idea of a<br />

Schuykill Front Street was dropped, and<br />

numbering proceeded westward from the<br />

Delaware. Holme planned a center square<br />

to locate “buildings for publick concerns,”<br />

and designated eight-acre public squares in<br />

each quarter of the one-by-two-mile city.<br />

William Penn ruled the north-south streets<br />

should be numbered, and east-west streets<br />

should take their names from nature:<br />

Sassafras, Chestnut, Mulberry, and other<br />

trees, or, at the northern boundary of the<br />

city, Vine. Exceptions were the two main<br />

streets, High and Broad. In later years<br />

usage turned High into Market, because the<br />

marketplace was there. Cedar Street, the<br />

city’s southern boundary, became South.<br />

Mulberry became Arch because an arch<br />

carried it across Front Street. And because<br />

young men raced their horses on Sassafras<br />

Street, it became known as Race Street.<br />

COURTESY OF THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF PENNSYLVANIA.<br />

PORTRAITURE OF THE CITY OF PHILADELPHIA IN THE<br />

PROVINCE OF PENNSYLVANIA IN AMERICA BY THOMAS<br />

HOLME, SURVEYOR GENERAL, ENGRAVING, 1683<br />

(OF610 1683H-1).<br />

CHAPTER I<br />

13

house faster than English carpenters using<br />

saws, planes, and fancy tools.<br />

The <strong>Philadelphia</strong>ns and their fellow<br />

Pennsylvanians in the countryside found,<br />

with the help of the Lenni Lenape, all sorts of<br />

fruits, berries and herbs growing wild. They<br />

began to cultivate grains and vegetables, raise<br />

horses and livestock, hunt deer and wild fowl<br />

and bring in fish, oysters, and mussels.<br />

It seemed just the kind of Sylvania that<br />

Penn had in mind.<br />

GOVERNOR PENN ARRIVES<br />

✧<br />

Thomas Fairman’s brick mansion at<br />

Shackamaxon on the Delaware was William<br />

Penn’s first residence in Pennsylvania.<br />

Nearby was a giant elm tree under which,<br />

deep <strong>Philadelphia</strong> tradition insists, Penn<br />

made his major treaty with the Lenni<br />

Lenape sachems (or sakima, the Lenni<br />

Lenape word for king or chief).<br />

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR.<br />

HISTORIC PHILADELPHIA<br />

14<br />

into the Delaware River bank, the tops planked<br />

over and covered with sod, and lived there<br />

until properly settled. (Benjamin Chambers,<br />

who arrived later with Penn on the ship<br />

Welcome, a carpenter good with his hands,<br />

built such an elaborate cave that he didn’t want<br />

to leave and eventually had to be forced by the<br />

authorities to accept a normal building lot.)<br />

Most settlers wanted to be near the river,<br />

the main thoroughfare for travel and<br />

commerce. Few wanted to be off in the<br />

woodsy interior. Holme drew a start-up layout<br />

that went only five blocks back from the river,<br />

started surveying lots, and had a lottery to see<br />

which buyer got which lot.<br />

Supplies were coming in by ship, and the<br />

Swedes and Indians sold the newcomers food<br />

and other commodities. There was plenty of<br />

timber for building, and good local clay for<br />

making red brick, as well as four shiploads of<br />

bricks, some forty-eight thousand, that arrived<br />

from England in 1682. Sand and gravel were<br />

plentiful for mixing mortar for brick<br />

construction. (Zachariah Whitpaine tried to<br />

economize a bit by mixing ground up oyster<br />

shells with his mortar, thus achieving the<br />

distinction of being the first <strong>Philadelphia</strong>n to<br />

have his house collapse.)<br />

For a low price, a settler could hire a team<br />

of Swedes who would move onto a wooded<br />

building lot and, working with only axes and<br />

wooden wedges, chop down trees, render<br />

them into beams and boards, and build a<br />

On October 24, 1682, a sailing ship<br />

entered the Delaware Bay and began moving<br />

smoothly upstream. It was the Welcome,<br />

Captain Robert Greenaway, master, fifty-three<br />

days out of Deal, England. On board was<br />

William Penn, soon to see the site of the great<br />

city he had been planning for two years.<br />

The Welcome was a 284-ton, three-masted<br />

bark, 140 feet long and 26 feet at the widest.<br />

(By contrast, the Queen Elizabeth II is 67,000<br />

tons, 963 feet long.) Passengers were provided<br />

with bare wooden bunks in cramped cubicles.<br />

They had to bring their own food. They could<br />

store baggage below decks if they found room.<br />

Penn had brought along a disassembled flour<br />

mill and saw mill, plus furniture and woodwork<br />

for the mansion he planned to build,<br />

including carved doors and window frames.<br />

The open deck was equally crowded. Penn<br />

had brought several horses. Other livestock,<br />

chickens, turkeys, and ducks, mostly crated,<br />

was noisy and smelly. The best way for a<br />

passenger to bring his own food, without it<br />

spoiling, was alive.<br />

Of the 100 Friends on the eight-week<br />

voyage, thirty died of smallpox. Penn was<br />

immune, because he had survived the disease<br />

at age three. He spent the weeks tending the<br />

feverish sick, and encouraging them with<br />

inspirational sermons.<br />

The thirty-eight-year-old Quaker came<br />

ashore at New Castle at dusk on October 27<br />

and handed town officials legal papers from<br />

London, informing them that he was the new<br />

proprietor and governor of their colony. The<br />

next day, the Welcome moved sixteen miles<br />

north to Upland; Penn renamed it Chester.

There is no good record of Penn’s arrival at<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong>. Tradition has him rowing into<br />

the mouth of the creek picked for the site of<br />

the public boat landing, Dock Creek.<br />

Penn created six counties: <strong>Philadelphia</strong>,<br />

Bucks, Chester, and the “Three Lower<br />

Counties”, New Castle, Kent and Sussex. He<br />

appointed a sheriff for each, and ordered<br />

them to hold elections of three members of<br />

the Provincial Council and six members of the<br />

General Assembly. The first popularly-elected<br />

Assembly met on March 12, 1683. Giving all<br />

taxpayers the right to vote caused Dr.<br />

Nicholas More, president of the influential<br />

Free Society of Traders, to predict disaster<br />

for a colony “wherein every Will, Dick and<br />

Tom govern.”<br />

During his stay, Penn took over Thomas<br />

Fairman’s brick mansion at Shackamaxon, up<br />

the river from the city. He wanted to build his<br />

own manor house close to town, and for its<br />

site picked the highest spot with the best<br />

view, the place called Fair Mount. He never<br />

built his dream house; if he had, it would be<br />

where the Art Museum now stands. He did set<br />

in motion the construction of a country estate<br />

at Pennsbury, in Bucks County.<br />

LAND DEALS &<br />

“ GREAT PROMISES”<br />

William Penn’s first purchase from the<br />

Lenni Lenape was made by Markham on July<br />

15, 1682, mostly of Bucks County land<br />

including Pennsbury. A year later, Penn personally<br />

made five deals for land along the<br />

Delaware, agreements with the natives in<br />

which, he wrote, “great Promises past<br />

between us of Kindness and good<br />

Neighbourhood,” and by June 1684, had<br />

negotiated for five more tracts either near the<br />

city or extending west to the Susquehanna<br />

River. In 1685 and 1686, Penn’s agents would<br />

make two more purchases. Just what was<br />

being bought was not always precise. One<br />

purchase was measured from Conshohocken<br />

west “as far as a man can go in two days,”<br />

another from the Delaware “as far as a man<br />

can ride in two days with a horse.”<br />

The Lenni Lenape had their own way<br />

of doing things, and Penn tried to observe<br />

it. “They (tho in a kind of Community<br />

among themselves) observe property and<br />

Government,” he wrote. And in a letter to<br />

Markham, September 1683, Penn mentioned<br />

that “the Indians do make People buy over<br />

again that Land the people have not seated in<br />

some years after purchased, which is the<br />

practice also of all these Governments towards<br />

the People inhabiting under them.” About<br />

forty-five more ships arrived during 1683.<br />

While 10,000 of every 100,000 acres of<br />

Pennsylvania land were reserved for Penn, there<br />

was plenty to go around. Investors in England<br />

and Europe signed up.<br />

A German group with five of its eleven<br />

directors from Frankfurt am Main formed the<br />

Frankford Company and bought fifteen<br />

thousand acres. Its agent, Francis Daniel<br />

In 1857 Granville John Penn, greatgrandson<br />

of William Penn, gave the<br />

<strong>Historic</strong>al Society of Pennsylvania a<br />

wampum belt he said had been presented to<br />

his ancestor in 1682.<br />

COURTESY OF THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF<br />

PENNSYLVANIA, PHOTO BY WEAVER LILLEY.<br />

CHAPTER I<br />

15

✧<br />

Historians tend to pooh-pooh the Penn treaty<br />

at Shackamaxon as legend because no<br />

official record exists. But after the massive<br />

Treaty Elm blew down in a hurricane in<br />

1810, sentimental <strong>Philadelphia</strong>ns placed a<br />

monument on the spot in 1824. Today the<br />

site is a public park.<br />

COURTESY OF THE CITY OF PHILADELPHIA,<br />

DEPARTMENT OF RECORDS, CITY ARCHIVES.<br />

HISTORIC PHILADELPHIA<br />

16<br />

Pastorius, came to Pennsylvania in 1683.<br />

He soon moved to Germantown and became<br />

a Quaker.<br />

Welsh Quakers also formed land companies,<br />

some with the intent to buy large tracts and<br />

subdivide acreage among poorer Welshmen.<br />

In May 1684, the ship Isabella out of Bristol<br />

arrived from Africa with 150 slaves for sale. It<br />

was the only known slave ship to enter the<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong> port in the 1680s. The cargo sold<br />

out. Nicholas More bought four men; two ran<br />

away almost immediately. Dr. More, newly<br />

appointed by Penn as chief of the five justices of<br />

the provincial court, was busy dealing with a<br />

crime wave. “There is heare mutch robrey in<br />

City and Countrey,” he reported to Penn,<br />

“Breaking of houses, and stealing of Hoggs.” An<br />

Indian sachem named Nannecheschan was giving<br />

More a hard time over the case of a slave<br />

who, while drunk, snatched the sachem’s crown<br />

from his head on the street and ran away with<br />

pieces of it, which he sold to a Dutch baker.<br />

When Penn sailed back to England in August<br />

1684, there were 357 houses in <strong>Philadelphia</strong>.<br />

BACK IN ENGLAND<br />

William Penn arrived in London in<br />

October of 1684, rented a mansion in the<br />

Kensington section, and spent much time<br />

lobbying at court, hoping for favorable<br />

settlement of a boundary dispute with Lord<br />

Baltimore of Maryland. The following<br />

February, King Charles II had a stroke while<br />

shaving. His majesty was given the most upto-date<br />

medical treatment, including the<br />

application of red hot frying pans to his head,<br />

but he died anyway. His brother, the Duke of<br />

York, was proclaimed King James II.<br />

In 1686 Penn toured Europe, and in Holland<br />

he conferred secretly with Prince William of<br />

Orange, son-in-law of King James and the<br />

acknowledged Protestant leader of Western<br />

Europe. Two years later, William and his wife,<br />

Mary, landed in England and took over the<br />

throne. James II fled to France. The new rulers<br />

didn’t trust the rebellious Quaker: within a<br />

month, Penn was stopped by troops on a<br />

London street and hauled in for questioning. In<br />

1690 he was thrown into the Tower of London<br />

briefly “for some practices against the<br />

government.” In 1692 William and Mary took<br />

away Penn’s rights to Pennsylvania, and turned<br />

the administration over to the governor of New<br />

York. It took Penn thirty months of persuasion<br />

at court to regain control of his province.<br />

In the midst of all this, his wife, Gulielma,<br />

died in February 1694, at age fifty. He<br />

consoled himself by working, writing and<br />

preaching. On a preaching tour in 1695, he<br />

stopped at the house of Thomas Callowhill, a<br />

Quaker merchant in Bristol, England. Penn,<br />

then fifty-four, was smitten with Callowhill’s<br />

daughter, Hannah, who was twenty-four. He<br />

corresponded with Hannah and sent her gifts,<br />

and they were married in March 1696.<br />

Five weeks after the wedding, Penn’s oldest<br />

son, Springett, died. He was twenty. Of the<br />

seven children born to Guli Penn, only three<br />

had lived more than a year. Remaining in<br />

1696 were Letitia, seventeen, and William Jr.,<br />

fifteen. In January of 1699, not yet eighteen,<br />

Billy Jr. married Mary Jones of Bristol, the day<br />

after her twenty-second birthday.<br />

And William Sr. was preparing to sail back<br />

to Pennsylvania and spend the rest of his days<br />

at his manor house on the Delaware.<br />

TROUBLE IN<br />

PENNSYLVANIA<br />

Before Penn left for England in 1684, he<br />

appointed Dr. Thomas Lloyd as deputy

governor, to head the Pennsylvania government<br />

in his absence. Lloyd was a Quaker physician<br />

who meant well, but lacked the clout of<br />

personality and reputation that Penn had. He<br />

was often ignored by <strong>Philadelphia</strong> settlers, who<br />

began to neglect rents and fees owed to Penn.<br />

Now that the governor was an ocean away,<br />

obligations of payment “are laid aside like an<br />

old tale told,” William Markham reported to<br />

Penn. The Provincial Council didn’t respond to<br />

Penn’s letters. Lloyd spent most of his time<br />

courting a wealthy widow in New York.<br />

Another Penn appointee was causing<br />

problems: Chief Justice Nicholas More, who<br />

had purchased ten thousand acres for himself,<br />

the Manor of Moreland northeast of the city.<br />

The Provincial Council impeached More in<br />

1685. The charges related to improper<br />

conduct in court, but it didn’t help that More,<br />

an Anglican, had publicly called the mostly<br />

Quaker Council “fools and loggerheads,” and<br />

said that “it will never be good times so long<br />

as the Quakers have the administration.”<br />

More refused to attend his hearing before the<br />

Assembly, and it was found that his secretary<br />

had kept the court records in a Latin<br />

shorthand that was indecipherable. The<br />

Assembly proclaimed More’s behavior<br />

“undecent, unallowable and to be disowned.”<br />

The arguments continued for two years, until<br />

More settled the matter by dying.<br />

As reports of the performance of the<br />

Pennsylvania government reached London,<br />

William Penn wrote to Thomas Lloyd, “For<br />

the love of God, me, and the poor country, be<br />

not so governmentish….”<br />

The Provincial leaders found time for some<br />

constructive actions during all the bickering.<br />

A ferry service was set up across the<br />

Schuylkill at High Street. Roads were cleared<br />

from <strong>Philadelphia</strong> to Moyamensing, Radnor,<br />

Plymouth and Darby. The wide grassy strip<br />

in the center of High Street was developing<br />

into a central market, where butchers grazed<br />

animals, slaughtered them and sold the<br />

meat in moveable stalls. The Quakers<br />

established a school in 1689, now called Penn<br />

Charter School.<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong> was getting the reputation of<br />

a wild town, from tales told by happy sailors<br />

and outraged Quakers. “There is a cry come<br />

over into these parts,” Penn complained from<br />

London, “against the number of drinking<br />

houses and the looseness that is committed in<br />

the caves,” meaning the dugouts on the<br />

waterfront that early settlers had used as<br />

temporary housing.<br />

Penn needed a tough on-site deputy governor.<br />

In 1688 he hired John Blackwell, a former<br />

captain in Oliver Cromwell’s Puritan<br />

army, who was roundly resisted when he<br />

arrived in <strong>Philadelphia</strong> and tried to run the<br />

government. The Council split into Blackwell<br />

and Lloyd factions, and political arguing was<br />

incessant. Blackwell lasted until 1690, then<br />

resigned, commiserating with Penn: “Alas!<br />

Alas! Poor governor of Pennsylvania!”<br />

Lloyd regained control, and chartered<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong> as a city, appointing Humphrey<br />

Morrey as the city’s first mayor. Morrey (or<br />

Murray, or Merry, depending on which<br />

document you read) grazed sheep on his<br />

property along Walnut Street, but it isn’t clear<br />

what else he did. He eventually settled in<br />

Cheltenham Township.<br />

Delegates from the Lower Counties walked<br />

out of the Assembly in 1691, disagreeing with<br />

the Quakers who opposed setting up river<br />

defenses for the colony. Lloyd allowed them<br />

to form their own government, effecting the<br />

precedent that would one day create the state<br />

of Delaware.<br />

✧<br />

Dr. Thomas Wynne, William Penn’s<br />

physician, built the first section of his house<br />

in 1690 and called it Wynnestay. “Stay”<br />

means “field” in Welsh, and the<br />

neighborhood around Wynnestay is now<br />

called Wynnefield. The house was expanded<br />

in the eighteenth century and is still<br />

privately owned.<br />

COURTESY OF SAUL WEINER.<br />

CHAPTER I<br />

17

This happened as King William took<br />

control of Pennsylvania. A royal governor,<br />

Benjamin Fletcher from New York, rode<br />

into <strong>Philadelphia</strong> with a military escort on<br />

October 24, 1692, where he antagonized the<br />

citizens by establishing a real estate tax, but<br />

also established a school and a rudimentary<br />

postal service.<br />

When the crown restored the province to<br />

William Penn’s control in 1694, Thomas<br />

Lloyd had died. Penn named William<br />

Markham deputy governor again, and the rest<br />

of the decade was a time of growth.<br />

The Quaker Yearly Meeting in 1696<br />

advised that “the Friends be careful not<br />

to encourage the bringing in any more<br />

Negroes.” It recommended taking slaves to<br />

religious meetings, and to “restrain them from<br />

loose and lewd living” and “from rambling<br />

abroad.” Germantown Mennonites and<br />

Quakers had already publicly expressed<br />

sentiments against slavery.<br />

In England, back in charge, married again,<br />

William Penn was happily preparing to return<br />

to <strong>Philadelphia</strong>.<br />

FINAL<br />

FAREWELLS<br />

When the ship Canterbury sailed from<br />

England on August 22, 1699, aboard were<br />

William Penn, his daughter Letitia, and his<br />

new wife, Hannah, who was pregnant. Young<br />

Billy decided to stay in London; his wife was<br />

also expecting a baby. Also with Penn was his<br />

secretary, James Logan, twenty-five, a poor<br />

but scholarly Irish schoolteacher. They had<br />

boxes of books with them, and a stallion<br />

named Tamerlane.<br />

Early on Sunday morning, December 3,<br />

Penn came ashore at <strong>Philadelphia</strong>. He could<br />

see that some caves on the riverbank were still<br />

occupied, but brick houses were visible, too.<br />

Just north of the public landing at Dock<br />

Creek, Thomas Budd was building a row of<br />

ten connected houses, violating Penn’s<br />

original concept that every house should be<br />

surrounded by garden, and starting a<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong> architectural tradition. Most<br />

of the city’s houses were frame, but about four<br />

hundred were red brick. There were about<br />

2,000 buildings and 5,000 citizens, most<br />

crowded along the river in the half square<br />

mile centered on Second and High Streets.<br />

A small delegation of citizens welcomed the<br />

governor. None were Quakers; the Friends<br />

were still at worship. Penn walked to the<br />

meeting house at Second and High, entered in<br />

the middle of meeting and offered a prayer.<br />

The Penn family stayed at Edward Shippen’s<br />

house at Second and Spruce for a month, then<br />

✧<br />

William Rittenhouse set up the first paper<br />

mill in America on a stream near the Falls<br />

of the Schuykill in 1690, and built this<br />

house in 1707. The family constructed flour<br />

and grist mills nearby over the next century,<br />

and Rittenhouse Village remains as a<br />

historic site. Mills popped up on other<br />

streams all over the area in William<br />

Penn’s time, and settlers also began<br />

producing such necessities as rope, beer,<br />

and glass in the city, ships on the Delaware,<br />

and linen in Germantown.<br />

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR.<br />

HISTORIC PHILADELPHIA<br />

18

moved to the Slate Roof House, on the east side<br />

of Second Street just above Walnut. Teenaged<br />

Letitia hung out with the boy next door, Will<br />

Masters, whose family was one of the richest in<br />

the city. And in January, Hannah Penn gave birth<br />

to a son, John, the only American-born Penn,<br />

described by neighbor Isaac Norris as “a comely,<br />

lovely babe.” School teacher Francis Pastorious,<br />

up in Germantown, assigned all eight boys<br />

named John in his class to write greetings to the<br />

new baby and send them to Penn.<br />

The proprietor kept busy attending<br />

Friends meeting, arguing with politicians,<br />

and, in 1701, producing a charter for the<br />

city of <strong>Philadelphia</strong>, under which Edward<br />

Shippen became the first elected mayor.<br />

Back in England, there were again rumbles<br />

about the crown taking control of the North<br />

American colonies. Penn became convinced<br />

that a trip to England was necessary. He<br />

wanted the family to stay behind, but Hannah<br />

refused to remain alone at Pennsbury.<br />

The Penns sailed on November 3, 1701,<br />

and twenty-eight days later were in London<br />

for a planned short visit. On March 8, 1702,<br />

King William died after his horse threw him<br />

while hunting. The next day, Hannah Penn<br />

gave birth to a son, Thomas. (She would bear<br />

five more children over the next six years.)<br />

Her husband was busy trying to help the<br />

Quakers gain the friendship of the new<br />

monarch, corpulent Queen Anne, William’s<br />

sister-in-law and the daughter of James II. The<br />

government was probing into Penn’s title to<br />

the Lower Counties on Delaware, which Lord<br />

Baltimore insisted should belong to Maryland,<br />

and there were complaints that Penn’s pacifist<br />

colony refused to support England’s current<br />

war effort against France and Spain.<br />

Penn’s troubles began multiplying. Letitia<br />

married a Welsh widower named William<br />

Aubrey, who demanded a cash dowry that<br />

put Penn in debt. Hannah called Aubrey a<br />

“muck-worm.” Billy Penn, Jr., his wife<br />

expecting their third child, was running<br />

up liquor bills all over London, which his<br />

father refused to pay. Penn insisted that young<br />

Bill go to <strong>Philadelphia</strong>, where he behaved<br />

no better. And the widow of Phillip Ford,<br />

Penn’s former business manager, was suing<br />

Penn for alleged back debts. On January 7,<br />

1708, bailiffs yanked Penn out of a Friends<br />

meeting where he was preaching, and locked<br />

him up for non-payment of debt. While he<br />

was in prison, his five-year-old daughter,<br />

Hannah, died, and his wife delivered another<br />

daughter, again named Hannah, who lived<br />

less than five months.<br />

✧<br />

Pennsbury was William Penn’s dream house<br />

in Bucks County. In April 1700, the Penn<br />

family left the city and climbed into the<br />

governor’s barge with the Penn coat of arms<br />

on the front. Six oarsmen propelled them up<br />

the Delaware to their new mansion.<br />

Hannah and Letitia began housekeeping,<br />

while Penn did what anyone does who has<br />

just had a house built: complained to the<br />

builder. He had specified an all brick house<br />

with brick foundations, but the builder had<br />

made the rear of wood and the foundation<br />

of stone. And the cistern on the roof leaked.<br />

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR.<br />

CHAPTER I<br />

19

Life briefly began looking better. Penn<br />

made arrangements that settled some of his<br />

problems with finances and with the throne.<br />

But in 1712, he suffered three strokes that left<br />

him incapacitated. In what a Quaker visitor<br />

described as “a state of innocency,” Penn<br />

vegetated, sipping lemon flavored brandy and<br />

letting Hannah function as de facto proprietor<br />

of his colony, guiding her husband’s<br />

uncontrolled hand to sign papers.<br />

Queen Anne died in 1714, and none of her<br />

seventeen children had survived her.<br />

Parliament had voted in 1689 that no Roman<br />

Catholic could ever again rule England, so<br />

Anne’s closest Protestant relative, cousin<br />

George of Hanover, a German state, became<br />

George I. He was barely interested in the job<br />

and never bothered to learn English.<br />

William Penn died on July 30, 1718, never<br />

having seen his creation, Pennsylvania, again.<br />

THE CITY’ S EARLY YEARS<br />

When Penn went to England in 1701, he<br />

named Andrew Hamilton lieutenant governor.<br />

The city council, which consisted of two<br />

groups, eight aldermen and twelve councilmen,<br />

was required to elect one of its members<br />

to be mayor for a year. Edward Shippen became<br />

the first elected mayor of <strong>Philadelphia</strong>, serving<br />

in 1701 and again in 1702. His son, Edward Jr.,<br />

would be mayor in 1744 and 1745. Shippen,<br />

Sr., lived on the west side of Second Street<br />

north of Spruce, and kept a herd of deer on his<br />

lawn. He also had a country home at Broad and<br />

South Streets.<br />

Shippen was succeeded by Anthony Morris<br />

in 1703. The council divided the city into ten<br />

parts. Each had a constable, who was expected<br />

to supply men to “serve upon the watch,” with<br />

nine men and the constable to “attend the<br />

watch each night.” A fourteen-by-sixteen-foot<br />

watch house was built in the market place. A<br />

tax of twelve pence per annum was placed on<br />

all cows two years and older, toward the<br />

upkeep of the two town bulls. An ordinance<br />

was drawn up to regulate taverns and public<br />

houses. Seven men and one woman were sent<br />

for by council and “admonished to take care<br />

how they drive their Carts within this City….”<br />

✧<br />

William Penn was a witness in 1700 at the<br />

dedication of the Swedish Lutheran church<br />

building that replaced an old fortified block<br />

house just south of the city. Gloria Dei, still<br />

in use, is now an Episcopal church and<br />

popularly known as Old Swedes.<br />

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR.<br />

HISTORIC PHILADELPHIA<br />

20

Governor Hamilton died in 1703. Penn’s<br />

next appointment was John Evans, twentysix,<br />

“sober and sensible, the son of an old<br />

friend,” according to Penn. Evans arrived in<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong> in 1704, and with him came<br />

William Penn, Jr.<br />

Young Billy was twenty-three, a widower of<br />

about a year, who left behind two hundred<br />

pounds of entertainment debts for his father<br />

to pay in London. Penn wrote to James Logan<br />

to keep an eye on Billy, pleading: “Allow no<br />

rambling in New York.” Logan permitted Billy<br />

one pound a week spending money.<br />

John Evans made a stab at governing, but<br />

his interests lay elsewhere. He and Billy lived<br />

in William Clarke’s “Great House” at Third<br />

and Chestnut Streets, and kept it well<br />

equipped with liquor, hunting dogs, and<br />

visiting young women.<br />

One muggy September evening, Billy,<br />

Governor Evans and some cronies were<br />

hoisting a few in the not completely reputable<br />

tavern of Enoch Story in Pewter Platter Alley,<br />

near Christ Church. Things got a bit<br />

boisterous, and the watchmen were called.<br />

Led by Alderman Joseph Wilcox, the<br />

watchmen suggested that the carousers hold it<br />

down. The situation escalated, and at one<br />

point, Wilcox punched Billy Penn in the face.<br />

The episode was smoothed over. A few weeks<br />

later, Billy Penn renounced the Society of<br />

Friends, buckled on a sword, sold his<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong> land cheaply to Isaac Norris,<br />

and went back to England after only nine<br />

months as a Pennsylvanian, leaving a stack<br />

of unpaid bills. (The Norris holdings would<br />

one day bring forth Norristown and two<br />

Norriton townships.)<br />

Evans stayed on, and soon was in another<br />

tavern brawl. Constable Solomon Cresson<br />

reported that he was “bidding a lewd tavernkeeper<br />

disperse her company” when some<br />

patrons got rough. Alderman Wilcox was<br />

summoned, and took the opportunity to slug<br />

the governor with a cane before (he maintained)<br />

he recognized him. The incident made Wilcox a<br />

celebrity. The next year he was elected mayor.<br />

Common Council’s minutes in 1712<br />

indicated that, “The Poor of this City Dayly<br />

Increasing,” a workhouse was needed. In<br />

1713 it was ruled that a new gaol (pronounced<br />

jail) was also needed. The Quakers built an<br />

Almshouse to shelter the homeless, on the<br />

south side of Walnut between Third and<br />

Fourth. There would be charitable buildings<br />

there through the years, as late as 1876.<br />

William Bradford had come from England in<br />

1685 and did the first printing in town.<br />

His work included some religious pamphlets<br />

the Quaker establishment didn’t care for. In<br />

1693 he was run out of town and moved to<br />

New York. His son Andrew brought the print<br />

shop back to <strong>Philadelphia</strong> in 1718, and in<br />

1719, Andrew Bradford published the American<br />

Weekly Mercury, the city’s first newspaper.<br />

The Quaker administration was undoubtedly<br />

disturbed to find that the Swedes<br />

and the Dutch were inclined to boisterous<br />

holiday celebrations. Much musket firing was<br />

done on New Year’s Eve, March 24 by the<br />

calendar then in use, and at Christmastime. A<br />

British custom of going door-to-door in<br />

costume, asking for food and drink, also had<br />

aspects that upset the Quaker authorities. In<br />

1702 a grand jury accused a man of “being<br />

maskt or disguised in women’s apparel; stalking<br />

openly through the streets of the city from<br />

house to house” on the day after Christmas,<br />

which is still a traditional day for Christmas<br />

pantomiming in England. A woman was<br />

charged with being on the street “dressed in<br />

man’s Cloathes, contrary to ye nature of her<br />

sects.” Both the costumes and the gunfire were<br />

early stages of the Mummers tradition that still<br />

erupts, in more organized form, every New<br />

Year’s Day.<br />

✧<br />

In 1709, the first city government building,<br />

a town hall and courthouse, was built in the<br />

middle of High Street at Second Street, at<br />

the head of the developing market sheds<br />

which would soon lead High to be popularly<br />

called Market Street. The site was across<br />

from the Great Meeting House the Quakers<br />

had erected in 1695. The balcony of the<br />

Courthouse became a speaking platform for<br />

politicians and preachers. The Provincial<br />

Assembly and City Council would meet<br />

there for a quarter century.<br />

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR.<br />

CHAPTER I<br />

21

HISTORIC PHILADELPHIA<br />

22

BEN FRANKLIN’S CITY<br />

THE KID FROM BOSTON<br />

On a late spring Sunday morning in 1723, a scruffy looking seventeen-year-old kid strolled into<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong>, and the city would never be the same. His name was Benjamin Franklin. His working<br />

clothes were rumpled from a rain-soaked trip through New Jersey, and down the Delaware in an<br />

open boat. His pockets and inside his shirt bulged with extra socks and shirts. He was tired from<br />

helping to row. He had one Dutch dollar with him.<br />

He was the third youngest of thirteen brothers and sisters. He could read as far back as he could<br />

remember, and at the age of twelve he was working in the Boston printing shop of his brother<br />

James. Unable to get along with his brother, Ben ran away to <strong>Philadelphia</strong>. On that Sunday<br />

morning, he struggled up the river bank from the boat, and bought three big rolls for a penny a<br />

piece from a bakery in Second Street near the market. He strolled out High Street, munching a roll.<br />

A girl about his age, standing in a doorway, giggled at the sight of the gawky boy and his<br />

ambulatory breakfast. Franklin couldn’t have guessed that this was his first sight of his future wife.<br />

Franklin got a job with Samuel Keimer in his printing shop on Second Street opposite Christ<br />

Church. Looking for a room to rent, he was sent by Keimer to the house of John Read on High Street.<br />

His new landlord’s daughter, Franklin was startled to find, was the girl who had laughed at him as he<br />

straggled past on his first day in town. Debbie Read was a hefty, well-built girl, and pretty enough.<br />

She was not as brilliant and well informed as Franklin might have wished, but they liked each other.<br />

Franklin soon developed a circle of friends his own age who liked to read and were good conversationalists.<br />

His reputation grew.<br />

The lieutenant governor since 1717 was Sir William Keith, thirty-eight, suave and fashionable,<br />

the son of a Scottish baronet. Keith approached Franklin, and offered to set the teenage printer up<br />

in business. Keith dazzled Franklin by suggesting that the lad go to London to buy printing<br />

equipment. In the fall of 1724, Franklin and Debbie Read “interchanged some promises” and he<br />

sailed for England. Keith told Franklin that letters of introduction and credit were in the captain’s<br />

dispatch bag. When the ship entered the English Channel on the day before Christmas, the captain<br />

opened his bag, and there were no such letters there.<br />

It would be months before a ship sailed for <strong>Philadelphia</strong>, and Franklin didn’t have the fare,<br />

anyway. He got work as a printer. Then, a <strong>Philadelphia</strong> Quaker merchant in London offered to pay<br />

Franklin’s way home and give him a job in a store. Franklin agreed. On October 11, 1726, he was<br />

once again walking up High Street.<br />

Franklin worked in the store for a while, but before long was managing Keimer’s print shop. He<br />

also organized the Junto, a club of his “ingenious acquaintances,” who met regularly “for mutual<br />

improvement” and pooled their books for membership use. Out of that came Franklin’s founding<br />

of the first subscription library in North America, the Library Company of <strong>Philadelphia</strong>.<br />

In 1728, Franklin started his own printing business, and the next year, began publishing a<br />

newspaper, the Pennsylvania Gazette. He started an annual almanac, published under the name<br />

Poor Richard, in 1733.<br />

On September 1, 1730, Franklin and Debbie declared themselves married under common law.<br />

About six months after the marriage, Franklin brought home a newborn son. He never identified<br />

the mother. The Franklins never discussed the situation publicly, named the baby William, and<br />

raised him without apology. The lamps in the print shop on High Street often burned until 11 p.m.<br />

as Ben Franklin, early to rise and late to bed, became, at age twenty-four, one of the best regarded<br />

and most prosperous businessmen in North America’s leading city.<br />

Ben may have found time to take in a show occasionally. Despite Quaker attempts to pass laws<br />

against “plays, games, lotteries, music and dancing,” <strong>Philadelphia</strong>ns managed to participate in such<br />

✧<br />

Benjamin Franklin had this portrait painted<br />

in 1759, when he was fifty-three. British<br />

officers confiscated it from Franklin’s house<br />

during the Revolution, and sent it to<br />

England. It was returned in 1906 and is<br />

now at the White House.<br />

COURTESY OF THE WHITE HOUSE COLLECTION.<br />

CHAPTER II<br />

23

✧<br />

Andrew Hamilton, whose slick work in a<br />

New York court in 1735 established freedom<br />

of the press as a concept of British law, drew<br />

the plan for the Pennsylvania State House<br />

in 1732. It would one day be known as<br />

Independence Hall.<br />

COURTESY OF THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF PENNSYLVANIA.<br />

ELEVATION OF THE STATE HOUSE ATTRIBUTED TO ANDREW<br />

HAMILTON (ACCESSION #BC47-H18).<br />

HISTORIC PHILADELPHIA<br />

24<br />

sinfulness. The first indication of a theater was<br />

in 1723, when “a Player who had Strowled<br />

hither to act as a Comedian” set up some kind<br />

of stage “without the verge of the City.” It<br />

would be standard practice for years to house<br />

entertainment across Cedar Street (now South<br />

Street) and thus outside city jurisdiction.<br />

Mayor James Logan lamented “How grievous<br />

this proves to the sober people of the place,”<br />

but since Governor Keith was a regular at the<br />

shows, they were unlikely to be outlawed. In<br />

1724, the first thing close to being a theater<br />

building appeared, “The New Booth on<br />

Society Hill,” featuring, according to<br />

advertisements, “your old friend Pickle<br />

Herring” (an Elizabethan clown name.)<br />

William Penn’s will left his Pennsylvania<br />

holdings to his sons by Hannah. John, then<br />

eighteen, got half. The other half was divided<br />

among Thomas, fifteen; Richard, twelve; and<br />

Dennis, eleven. Billy, from the first marriage,<br />

was granted the family’s Irish lands and the<br />

title of Proprietor of Pennsylvania. He had<br />

already inherited his mother’s extensive<br />

properties. Billy’s two sons, and his sister,<br />

Letitia, each were bequeathed ten thousand<br />

acres in Pennsylvania.<br />

Billy contested the will, claiming that all of<br />

Pennsylvania and Delaware should be his.<br />

Billy died in 1720, at age forty. His son<br />

Springett, nineteen, continued the suit. The<br />

case dragged on until 1726, when it was ruled<br />

that Penn’s will stood as written. Hannah<br />

Penn died a week later.<br />

BUILDING A STATE HOUSE<br />

The Provincial Assembly had decided in<br />

1729 that the Courthouse at Second and<br />

Market was getting crowded, and voted to<br />

build a State House, appropriating two<br />

thousand pounds for the project. Andrew<br />

Hamilton, a lawyer, who was speaker of the<br />

house, drew up a plan. So did Dr. John<br />

Kearsley, who had designed Christ Church.<br />

Hamilton’s prospective son-in-law, William<br />

Allen, who founded Allentown and Mount<br />

Airy, quietly began buying land on the edge of<br />

the built-up part of town, on Chestnut Street<br />

between Fifth and Sixth. When ground was<br />

broken in 1732, Kearsley raised a ruckus over<br />

both the design and the location. The<br />

assembly debated for several days, and gave<br />

the nod to Hamilton. Then, to the builder’s<br />

annoyance, the legislators began making<br />

changes in the plan. It voted that two office<br />

wings should be added to the building.<br />

Hamilton had the alterations under way in<br />

summer of 1733, when the construction<br />

workers, under Edmund Wooley, a master

carpenter, struck for higher wages. It was<br />

1735 before the House met in the Assembly<br />

chamber of the building that would one day<br />

be called Independence Hall. The paneling<br />

was not installed and all the glass was not in<br />

the windows.<br />

John Bartram added a stone wing to his<br />

house in 1731. The house was (and still is) on<br />

the west bank of the Schuylkill about three<br />

miles below Market Street. Bartram was born<br />

in 1699 and grew up on his father’s farm<br />

along the Darby Creek west of <strong>Philadelphia</strong>.<br />

One day, while sitting under a tree, resting<br />

from plowing, he picked a daisy and plucked<br />

it apart, as farm boys will. That simple<br />

moment led him to study Latin so he could<br />

read the botany books of the day. In 1728,<br />

Bartram bought 102 acres at sheriff’s sale. On<br />

it stood a one and a half story stone house of<br />

two tiny rooms, built before Bartram was born<br />

by Swedish settler Peter Peterson Yocumb.<br />

The fledgling botanist began developing a garden<br />

around it, with specimens of hundreds of<br />

native trees and plants. In 1731, he expanded<br />

the house and made the original part the<br />

kitchen. On the new wing, he carved his<br />

name and his new bride’s. The inscription can<br />

still be seen: “John, Ann Bartram, 1731.” And<br />

he kept collecting those plants.<br />

Benjamin Franklin instigated the start of the<br />

Union Fire Company, the first formal fire<br />

fighting organization, on December 7, 1736.<br />

Each member agreed to have six leather buckets<br />

and two osnaburg bags (coarse linen cloth), and<br />

to respond to cries of fire with at least half his<br />

buckets and bags, where the company would<br />

“exert our best endeavors to extinguish such<br />

fires, and preserve the goods and effects of such<br />

of us as may be in danger,” according to the<br />

written rules. Five more fire companies were<br />

organized in the next sixteen years.<br />

Anthony Palmer, a British sea captain from<br />

Barbados, had bought “several parcels of land,<br />

meadow, swamp and cripple” along the<br />

Delaware above the city about 1704, and<br />

lived on his Hope Farm there until 1729.<br />

Then he sold the place to William Ball,<br />

who renamed the estate Richmond Hall,<br />

providing a name for a future <strong>Philadelphia</strong><br />

neighborhood. Palmer bought the Fairman<br />

place down the river at Shackamaxon. Thomas<br />

Fairman had died in 1714. The captain bought<br />

191 adjoining acres, and set to work laying out<br />

streets and selling building lots. He called the<br />

development Kensington. A marketing ploy<br />

was to establish a cemetery, and offer a burial<br />

lot there to each purchaser. Palmer’s daughter,<br />

Thomasine, in her will written soon after her<br />

father’s death in 1749, left the cemetery “to be<br />

freely occupied and enjoyed by all the<br />

inhabitants of Kensington forever.” Inhabitants<br />

of the old, original part of Kensington, now<br />