You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

34 / PEOPLE / Conservationists<br />

PEOPLE / 35<br />

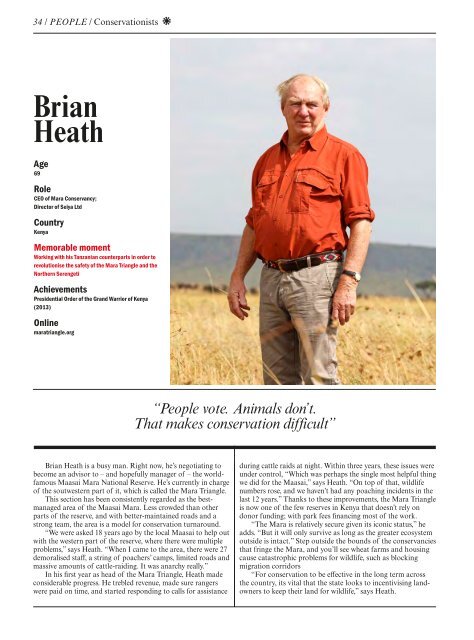

Brian<br />

Heath<br />

Age<br />

69<br />

Role<br />

CEO of Mara Conservancy;<br />

Director of Seiya Ltd<br />

Country<br />

Kenya<br />

Memorable moment<br />

Working with his Tanzanian counterparts in order to<br />

revolutionise the safety of the Mara Triangle and the<br />

Northern Serengeti<br />

Achievements<br />

Presidential Order of the Grand Warrior of Kenya<br />

(2013)<br />

Online<br />

maratriangle.org<br />

Thandiwe<br />

Mweetwa<br />

Age<br />

31<br />

Role<br />

Senior ecologist at the Zambian Carnivore<br />

Programme; manager of the organisation’s<br />

Conservation Education Programme<br />

Country<br />

Zambia<br />

Memorable moment<br />

Becoming a National Geographic Emerging Explorer<br />

in 2016<br />

Achievements<br />

Alumnus of the Obama Foundation’s 2018 Leaders:<br />

Africa programme<br />

Online<br />

zambiacarnivores.org<br />

Edward Selfe<br />

“People vote. Animals don’t.<br />

That makes conservation difficult”<br />

“I remember my mother’s vivid stories about the local wildlife when<br />

she was growing up; they sparked my fascination with nature”<br />

Brian Heath is a busy man. Right now, he’s negotiating to<br />

become an advisor to – and hopefully manager of – the worldfamous<br />

Maasai Mara National Reserve. He’s currently in charge<br />

of the soutwestern part of it, which is called the Mara Triangle.<br />

This section has been consistently regarded as the bestmanaged<br />

area of the Maasai Mara. Less crowded than other<br />

parts of the reserve, and with better-maintained roads and a<br />

strong team, the area is a model for conservation turnaround.<br />

“We were asked 18 years ago by the local Maasai to help out<br />

with the western part of the reserve, where there were multiple<br />

problems,” says Heath. “When I came to the area, there were 27<br />

demoralised staff, a string of poachers’ camps, limited roads and<br />

massive amounts of cattle-raiding. It was anarchy really.”<br />

In his first year as head of the Mara Triangle, Heath made<br />

considerable progress. He trebled revenue, made sure rangers<br />

were paid on time, and started responding to calls for assistance<br />

during cattle raids at night. Within three years, these issues were<br />

under control, “Which was perhaps the single most helpful thing<br />

we did for the Maasai,” says Heath. “On top of that, wildlife<br />

numbers rose, and we haven’t had any poaching incidents in the<br />

last 12 years.” Thanks to these improvements, the Mara Triangle<br />

is now one of the few reserves in Kenya that doesn’t rely on<br />

donor funding; with park fees financing most of the work.<br />

“The Mara is relatively secure given its iconic status,” he<br />

adds. “But it will only survive as long as the greater ecosystem<br />

outside is intact.” Step outside the bounds of the conservancies<br />

that fringe the Mara, and you’ll see wheat farms and housing<br />

cause catastrophic problems for wildlife, such as blocking<br />

migration corridors<br />

“For conservation to be effective in the long term across<br />

the country, its vital that the state looks to incentivising landowners<br />

to keep their land for wildlife,” says Heath.<br />

Lions are vanishing. Their numbers have halved in the last 25<br />

years, leading to the classification as vulnerable to extinction by<br />

the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).<br />

Zambia, and the Luangwa Valley in particular, is one of the<br />

last strongholds for the larger African carnivores. With roughly 40<br />

percent of the country’s land set aside for wildlife, and strong buffer<br />

zones for lion parks, these apex predators have a good chance of<br />

survival here. “Luangwa holds Zambia’s biggest lion and leopard<br />

populations and its second-largest wild dog population. So ecologically,<br />

it’s a key area,” said Thandiwe Mweetwa in an interview with<br />

BUCKiT.<br />

It is, therefore, the perfect place for research. Mweetwa, whose<br />

initial career choice of wildlife vet failed due to a fear of blood,<br />

successfully turned her attention instead to ecology and biology,<br />

and works to map the patterns of human-carnivore interaction as<br />

they shift, so she’s often tracking and studying different lion or wild<br />

dog groups. As well as rescuing snared animals, she liaises with<br />

communities whenever there are human-animal conflicts, and she<br />

runs a programme to educate youths about conservation.<br />

“We need to balance the ‘boots on the ground’ approach with<br />

meaningful engagement with disenfranchised communities,” she<br />

says. “In the next decade, we’ll be faced with the daunting task of<br />

rapid economic development coinciding with biodiversity protection.”<br />

Partly to address this, Mweetwa set up Women in Wildlife<br />

Conservation in 2016. Participants receive full instruction in all<br />

aspects of conservation work, and this vital information is integrated<br />

into secondary school- and community education.<br />

“What makes me hopeful about the work that I do, and conservation<br />

work in general, is that most of the problems are tied to<br />

human behaviour,” adds Mweetwa. “As a global community, we<br />

need to cultivate a sense of pride in our shared natural heritage,<br />

and realise that only collective effort will make a difference.”