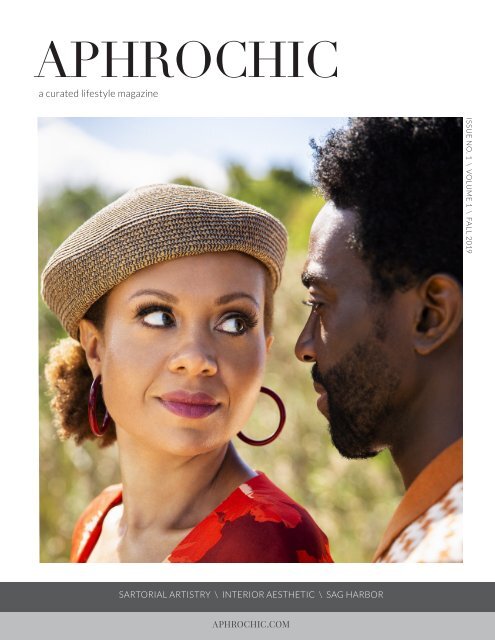

AphroChic Magazine: Issue No. 1

Welcome to the Fall 2019 issue of AphroChic Magazine. Designed to celebrate the presence, innovation and accomplishments of creatives of color from all corners of the African Diaspora, we welcome the season in this issue with a focus on fashion, authentic beauty, and creating moments that bind us together. On the cover, New York fashion stylists, Courtney and Donnell Baldwin of Mr. Baldwin Style invite us to experience a fête in a historic part of Sag Harbor. We take a look inside the Brooklyn home of fashion designer and movement artist, Nana Yaa Asare-Boadu and experience her effortless aesthetic. Then, we go half way around the world on a photographic journey of Morocco, with photographer Lauren Crew. Along the way, you’ll find articles that explore the nature of the African Diaspora, the importance of the Black family home, and the books, art and accessories you’ll want to bring home this season.

Welcome to the Fall 2019 issue of AphroChic Magazine. Designed to celebrate the presence, innovation and accomplishments of creatives of color from all corners of the African Diaspora, we welcome the season in this issue with a focus on fashion, authentic beauty, and creating moments that bind us together.

On the cover, New York fashion stylists, Courtney and Donnell Baldwin of Mr. Baldwin Style invite us to experience a fête in a historic part of Sag Harbor. We take a look inside the Brooklyn home of fashion designer and movement artist, Nana Yaa Asare-Boadu and experience her effortless aesthetic. Then, we go half way around the world on a photographic journey of Morocco, with photographer Lauren Crew. Along the way, you’ll find articles that explore the nature of the African Diaspora, the importance of the Black family home, and the books, art and accessories you’ll want to bring home this season.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

APHROCHIC<br />

a curated lifestyle magazine<br />

ISSUE NO. 1 \ VOLUME 1 \ FALL 2019<br />

SARTORIAL ARTISTRY \ INTERIOR AESTHETIC \ SAG HARBOR<br />

APHROCHIC.COM

When <strong>AphroChic</strong> began, our blog was dedicated to highlighting the contributions<br />

of Black people in the world of design while providing content for smart, design<br />

savvy people of color - an audience we were often told did not exist. At first it<br />

was just a hobby, but things have a way of growing and <strong>AphroChic</strong> had a mind of<br />

its own. Two years after it started, our blog became a product line, then a book<br />

and after that an interior design company. <strong>No</strong>w, 12 years since our first blog post,<br />

we’ve come full circle.<br />

Four years ago we had the honor of speaking at Harvard’s first Black in Design Conference.<br />

It was an amazing event gathering hundreds of Black architects, designers,<br />

and students from all over the country. It was truly inspiring; yet as it went on, we<br />

realized how little we all knew about each other. It drove home to us the importance of<br />

increased representation - not just within the so-called “mainstream” - but in our own<br />

community. We realized how much we needed to see us, for us, and we decided to do<br />

something to help.<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong> has always been about filling voids. The blog looked to fill a void in a conversation<br />

that took no notice of Black creatives or a Black audience. We created products<br />

because we saw so few luxury items for the home that connected to our culture or represented<br />

our history. We wrote a book and designed spaces to show how rooms and the<br />

things we put in them can tell our story.<br />

With this magazine, we want to fill another void. We want to provide a platform for<br />

showcasing our presence and our talents, a lens for appreciating Black creativity in all<br />

fields. This isn’t a design magazine or even a lifestyle publication - it’s a quarterly love<br />

letter to the cultures of the African Diaspora, to the people who fought to create them<br />

and to those who work now to see them continue and evolve.<br />

In each issue, we will highlight stories of Black creatives in a variety of disciplines,<br />

industries, and fields while exploring the connections between art, design, architecture,<br />

food, technology, music, politics, and history that fit together to make a culture.<br />

Thank you for taking this first step with us. Welcome to <strong>AphroChic</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong>.<br />

Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Founders, <strong>AphroChic</strong><br />

Instagram: @aphrochic<br />

editors’ letter

Fall 2019<br />

DEPARTMENTS<br />

Read This, <br />

Visual Cues, <br />

A Family Affair, <br />

Coming Up, <br />

Mood, <br />

FEATURES<br />

Fashion // Sartorial Artistry, <br />

Interior Design // Interior Aesthetic <br />

Food // Food & Fellowship, <br />

Culture // A Day at the Beach, <br />

Travel // Morocco: A Photographic Journey, <br />

Reference // The Questions of Diaspora, <br />

PINPOINT<br />

Artists & Artisans, <br />

Hot Topic, <br />

Who Are You,

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

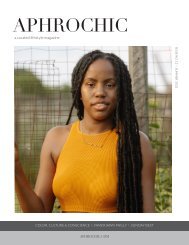

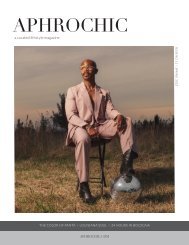

APHROCHIC<br />

a curated lifestyle magazine<br />

ISSUE NO. 1 \ VOLUME 1 \ SEPTEMBER 2019<br />

Cover Photo: Brittany Ambridge<br />

SAG HARBOR STORY \ BECOMING NINA \ VINTAGE VISION<br />

APHROCHIC.COM<br />

Publishers/Editors: Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Creative Director: Cheminne Taylor-Smith<br />

Contact:<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong><br />

Brooklyn, NY<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong>.com<br />

info@aphrochic.com<br />

Photo Contributors:<br />

Chinasa Cooper<br />

Lauren Crew<br />

Patrick Cline<br />

issue one

READ THIS<br />

Contemporary imagery showcasing art and culture across the African Diaspora is few<br />

and far between. But three recent books show another picture. In these works, we see<br />

catalogs of Black contributions in fine art, explore the photographs that brought visual<br />

representation to the Black is Beautiful movement, and explore the ways that people<br />

of African descent have not only influenced fashion, but set the standard for what it is.<br />

These books break new ground, adding an important element of self-recognition to the<br />

way we see the cultural institutions we love.<br />

Black Refractions: Highlights from the Studio<br />

Museum in Harlem. Written by Thelma Golden<br />

and Kellie Jones and Connie H. Choi.<br />

Publisher: Rizzoli Electa. $45<br />

Kwame Brathwaite: Black Is Beautiful.<br />

Essays by Tanisha C. Ford and Deborah<br />

Willis. Publisher: Aperture. $32<br />

How to Slay: Inspiration from the Queens and<br />

Kings of Black Style. Written by<br />

Constance C.R. White.<br />

Publisher: Rizzoli. $55<br />

<br />

aphrochic

VISUAL CUES<br />

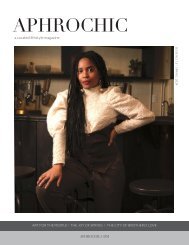

We are transfixed by Adepero Oduye’s short film, To Be Free. In the film, which<br />

showcases Oduye’s many talents as writer, directer and star, she transforms herself into<br />

the legendary Nina Simone. Filmed in Brooklyn, NY, with an intimate cast of friends<br />

and fellow actors, the audience is transported to the 1960s for a single impromptu<br />

performance by Miss Simone, where she is truly free. Having the opportunity to<br />

participate in the film as part of the audience, we saw first-hand the making of a film<br />

that not only celebrates an icon, but the freedom that can come in a moment of honest<br />

self-expression.<br />

Visit aphrochic.com to listen to our podcast with Adepero Oduye.<br />

Photography by Jenny Baptiste<br />

<br />

aphrochic

issue one

IT’S A FAMILY AFFAIR<br />

At the beginning of 1956, the Belfield area of Philadelphia was a predominantly white<br />

part of the city. With few exceptions, just about all of the African Americans to be found<br />

there were domestic workers, coming in and out of houses as they finished their work as<br />

maids. But in October of that year, a new family arrived. Made up of three generations<br />

- a grandmother, her four children, and two grandchildren - they were only the second<br />

Black family to move onto the block.<br />

My mother was a few days past<br />

her seventh birthday when she moved<br />

with her family into the new house.<br />

They came from <strong>No</strong>rth Philadelphia,<br />

and a house where they had<br />

lived along with even more family<br />

members. Purchasing the new home<br />

had been a group effort - one that<br />

required the whole family to pool<br />

their money together. But a new<br />

home meant new possibilities, and<br />

buying the home in Belfield eventually<br />

led to the purchase of others.<br />

The home was a row house,<br />

something of a staple in Philadelphia.<br />

Row homes are attached<br />

houses, appointed with sizable front<br />

yards and smaller back lots. With<br />

three-stories, three bedrooms, and<br />

a full basement, it was large enough<br />

for a family of six to live in comfortably.<br />

And over the next six decades,<br />

“the house,” as we’ve always called it,<br />

has been a cornerstone for my family.<br />

A place for holidays and casual visits,<br />

a place for kids to run and for pets to<br />

live, a perfect place for being together<br />

at any time and for any reason. While<br />

the list of occupants has changed over<br />

time, the house has always been ours<br />

and it’s always been there for anyone<br />

who needed it. Someone moving up<br />

from the South? They can stay at<br />

the house. A grandchild in need of<br />

a place to live after college? There’s<br />

room at the house. A new baby on<br />

<br />

aphrochic

the way, a friend in need - there is<br />

always room for family at the house.<br />

My family’s house is unique,<br />

but it’s far from being the only one<br />

of its kind. The Black family home is<br />

a significant cultural institution in<br />

America. So many of us recognize<br />

the warm feeling that comes from<br />

thinking of that one special house<br />

where the family can always be found.<br />

For people like my great-grandmother<br />

Lola Harper, affectionally<br />

called “Mama,” and her children,<br />

home ownership was not an easy path.<br />

Covenants that barred ownership<br />

and access to specific neighborhoods<br />

were common across the country in<br />

the 1950s and before. To purchase a<br />

home was a challenge, but well worth<br />

it, as ownership provided security<br />

for the family. It gave you something<br />

to call your own, something to<br />

pass down to future generations.<br />

Today, this institution is in<br />

danger. According to the US Census<br />

Bureau, home ownership among<br />

Black families dropped in 2019 to<br />

40.6%, the lowest it’s been since 1950.<br />

Beginning in 2007, the decline marks<br />

the complete erasure of progress<br />

made since the 1968 Fair Housing Act,<br />

which barred the discriminatory real<br />

estate practices that had always disenfranchised<br />

Black people seeking<br />

to own their own homes. Causes for<br />

the losses include predatory lending<br />

practices, subprime mortgages,<br />

and struggles with upkeep, but<br />

behind them all are many of the<br />

same attitudes that created barriers<br />

to Black home ownership in the<br />

past. For many Black families, “the<br />

house” is in danger of being lost.<br />

To preserve our family home<br />

of 63 years, we began an effort to<br />

update the space to keep it in good<br />

repair for years to come. The process<br />

has been an ethnographic study of<br />

my family, the community, and the<br />

importance of ensuring that the<br />

Black home remains a family affair.<br />

My mother was a child when she<br />

first moved into the house. Years later,<br />

she would inherit it from her mother<br />

as her mother had inherited it from<br />

Mama. Today, my sister lives there<br />

with her husband and son; and my<br />

wife and I continue the home’s legacy<br />

by being stewards for the next generation<br />

that will certainly call it home.<br />

It‘s a Family Affair is an ongoing series<br />

focusing on the history of the Black family<br />

home, stories from the Harper family,<br />

and the renovations and restorations of a<br />

house that bonds this family.<br />

Photos from Harper Family Archives<br />

Words by Bryan Mason<br />

issue one

COMING UP<br />

Events, exhibits, and happenings that celebrate and explore the African Diaspora.<br />

La Biennale di Venezia 2019<br />

Venice, Italy<br />

Through <strong>No</strong>v. 24<br />

Sculptor Martin Puryear is representing the United<br />

States in a solo exhibition, only the fourth African<br />

American artist to do so in the famed event’s 58-year<br />

history. Commissioned by Madison Square Park Conservancy,<br />

Puryer created A Column for Sally Hemings,<br />

above, specifically for the Venice Biennale.<br />

martinpuryearvenice2019.org<br />

Taste of Soul Festival<br />

Los Angeles<br />

Oct. 19<br />

The largest one-day street festival in Los Angeles, with<br />

over 350,000 attendees. Taste of Soul features local<br />

and international cuisine that reflects a Black cultural<br />

experience, fused with diverse cultures and traditions.<br />

It also includes five stages with major acts like Queen<br />

Latifah and Stevie Wonder.<br />

tasteofsoul.org<br />

Afro Syncretic<br />

New York<br />

<strong>No</strong>v. 8<br />

Afro Syncretic presents the work of nine artists highlighting<br />

the African roots of the Latinx diaspora. Collectively,<br />

the works center on the vibrancy of diasporic blackness<br />

within Latinx culture and urge viewers to confront dominant<br />

narratives of what it means to be Latinx.<br />

wp.nyu.edu/latinxproject<br />

<br />

aphrochic

MOOD<br />

Silhouette Pouf,<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong>, $555<br />

Broom Pouf,<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong>, $555<br />

<br />

aphrochic

Must-have products we have our eye on this season.<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong> x Dounia Home<br />

Handmade in Morocco, the Amur Table Lamp blends<br />

the centuries-old technique of creating pierced metal<br />

lanterns with modern lighting aesthetics. The perforated<br />

globes allow precision control of the amount of<br />

light in a space, while the abstract base adds a contemporary<br />

feel.<br />

Amur Table Lamp<br />

$1,250<br />

Jomo Furniture<br />

The Ashanti I stool is a modern interpretation of the<br />

traditional Ashanti stool from Ghana. Re-imagined<br />

in Baltic birch plywood with a sleek silhouette, this<br />

adjustable stool reflects a deep appreciation for traditional<br />

craftsmanship and modern style.<br />

Ashanti I<br />

$2,100<br />

Slate Eau de Parfum<br />

$95<br />

House of Linnic<br />

Edgy and seductive, Slate is an eclectic scent crafted<br />

to evoke the feel of New York City. Blending notes of<br />

white tea, frankincense, pepper and peony, its organic<br />

ingredients and essential oils fuse to create a sophisticated<br />

sensory experience, perfect for when you’re<br />

feeling irresistible.<br />

issue one

FEATURES<br />

Sartorial Artistry | Interior Aesthetic | Food & Fellowship | A Day at the<br />

Beach | Morocco: A Photographic Journey | The Questions of Diaspora

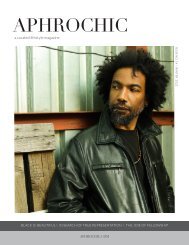

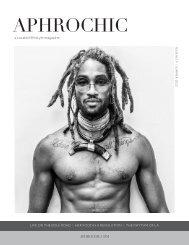

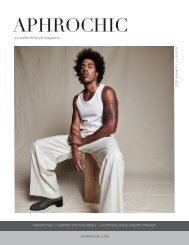

Fashion<br />

Sartorial<br />

Artistry<br />

Photos by Gregory Prescott<br />

Words by <strong>AphroChic</strong>: Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

<br />

aphrochic

With ankara fabric draped in a backyard in<br />

Brooklyn, photographer Gregory Prescott<br />

captures images of model, George Okeny. The<br />

author of By Window Light a nd t he upcom i ng Only<br />

HUMAN, Prescott has found his most enduring<br />

source of inspiration in capturing the human<br />

form. In his artist’s statement he writes, “My<br />

photographs have successfully embraced both<br />

the inner and outer beauty of men and women.<br />

GOD is the true artist. I am the channel.” In<br />

this sartorial series, Prescott explores the way<br />

that color, texture, and shape converse in the<br />

interplay of the body with fashion. With Okeny<br />

standing boldly in fall staples, like a leather<br />

coat and deeply-hued bomber, Prescott reveals<br />

to us this Sudanese model’s beauty, strength,<br />

and piercing humanity. AC<br />

Visit gregoryprescott.net to learn about the photographer’s<br />

self-produced first solo exhibition set for October 2019, and<br />

his next coffee table book, Only HUMAN.

Fashion<br />

<br />

aphrochic

aphrochic

issue one

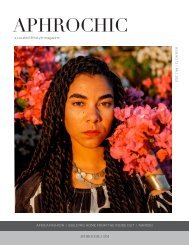

Interior Design<br />

Interior<br />

Aesthetic<br />

At Home with Fashion Designer<br />

Nana Yaa Asare-Boadu<br />

Photos by Patrick Cline<br />

Words by <strong>AphroChic</strong>: Jeanine Hays & Bryan Mason<br />

<br />

aphrochic

issue one

Interior Design<br />

<br />

aphrochic

“I’m not much of a talker,” says Nana Yaa Asare-Boadu, looking out the<br />

window of a Brooklyn cafe at all the activity of a morning in New York City.<br />

She says it quietly, the way she says most things, and though she’s here<br />

specifically for a conversation, her first confession is more believable than<br />

the next: “I don’t think that deeply about fashion.”<br />

But if there’s one thing to learn<br />

from Nana Yaa, it’s that not being much<br />

of a talker should never be confused<br />

with not having much to say. A career in<br />

fashion that has spanned major brands<br />

and nation-states has given her plenty<br />

to say about fashion, design, and the<br />

lopsided dialectic between honesty and<br />

commerce in the life of a creative. That<br />

doesn’t mean she wants to talk about it.<br />

“People should just do it,” she says. “Stop<br />

talking. Go places. See for themselves.<br />

Listen, and then have their views.”<br />

Nana Yaa is the definition of a global<br />

citizen. Born in London of Ghanaian<br />

ancestry and raised in Holland, her<br />

talents have taken her to Paris and<br />

Milan, with stays in Israel and Ghana.<br />

All of that before arriving in<br />

New York to assume a position with<br />

fashion house Jonathan Simkhai that<br />

now sees her time split between New<br />

York and Los Angeles. Along the way<br />

she’s acquired a fluency in French and<br />

Dutch, as well as a working knowledge<br />

of German and Twi.<br />

With so many countries to her<br />

credit, it’s not hard to imagine why<br />

talking is not one of her more valued<br />

pastimes. Perhaps a life lived between<br />

languages has given her an appreciation<br />

of all that words cannot do. Instead,<br />

Nana Yaa favors non-verbal forms of<br />

communication. Drawing, design, and<br />

issue one

Interior Design<br />

<br />

aphrochic

ecently dance are just a few of the<br />

ways she’s found to express herself.<br />

But perhaps her most complete exposition<br />

of who she is comes from the<br />

design of her Brooklyn pied-à-terre.<br />

Luxuriously sized for a city where<br />

cramped quarters are the norm, the<br />

two-story, one bedroom apartment is<br />

elegantly designed in an understated<br />

yet expressive way that blends family<br />

photos, touching gifts, and lucky<br />

finds from all over the world to tell a<br />

story as unique and intriguing as the<br />

designer herself.<br />

More than its space, the interior<br />

of the home has the kind of “bones”<br />

that interior designers dream of.<br />

Small architectural details, original<br />

to the home, are built into the walls<br />

and doorways bringing personality<br />

and interest into every room. It’s<br />

the perfect palette for an artist with<br />

so many stories to tell, and the type of<br />

find all New Yorkers dream of. “I was<br />

really lucky,” she recalls of the process<br />

of finding her home.<br />

Living in London and searching<br />

for apartments online, Nana Yaa came<br />

across her future home, and immediately<br />

dismissed it as too good to be<br />

true. “I told my mom, I’m never going<br />

to get it, but she kept saying, just call<br />

them. Just call them, so I did.” A call<br />

turned into a conversation and soon<br />

Nana Yaa dispatched a local friend<br />

to see the place firsthand and let her<br />

know what she was getting into. “You<br />

should get it,” was the quick reply.<br />

Stepping through the garden level<br />

entrance of the home presents visitors<br />

with an immediate choice: up the<br />

stairs to the right and to the second<br />

floor, down the hallway in the center,<br />

or through the open entryway to the<br />

left. Those who choose left will find<br />

themselves in an expansive dining<br />

room presided over by a beautiful<br />

reclaimed wood table. Generally unissue<br />

one

assuming despite its delightful<br />

texture and capacity to seat eight, no<br />

one would ever suspect that the table<br />

is a perfect example of how Nana Yaa<br />

decorates her home, and the types of<br />

stories that make up her life.<br />

“This was a beautiful surprise,” she<br />

smiles as she remembers. “It basically<br />

came with the house.” The table was<br />

one of several curiosities - including an<br />

antique deep sea diving helmet - that<br />

were waiting for her when she moved<br />

in. About a year later, Nana Yaa was on<br />

a job interview and her interviewer<br />

asked her about living in Brooklyn. He<br />

asked what neighborhood, what street<br />

and finally the address. After she’d<br />

answered, he revealed that he’d once<br />

lived in Brooklyn as well. Same neighborhood,<br />

same street, same address.<br />

“Do you still have that dining room<br />

table?” he asked. “I left one there when<br />

I moved out.”<br />

Nana Yaa’s home is less a space<br />

decorated in furniture and accessories<br />

and more a library of stories,<br />

each one encased in some seemingly<br />

mundane object yet curated and<br />

<br />

aphrochic

issue one

Interior Design<br />

<br />

aphrochic

issue one

Interior Design<br />

presented with as much care and<br />

style as great works by renowned<br />

masters. A narrow hallway between<br />

her dining room and her kitchen has<br />

been converted into a small yet dense<br />

library. In it, she reveals another of<br />

her decorating secrets. “I’m a bit of a<br />

hoarder,” she confesses, and books are<br />

high on her list of coveted items.<br />

From an early age, the designer<br />

wanted nothing more than books for<br />

birthdays, holidays or any occasion<br />

where gifts were a possibility. Over<br />

the years her collection has grown<br />

and, quickly exceeding the confines<br />

of these few shelves, Nana Yaa’s books<br />

are a constant presence in every<br />

room. On tables they become objects<br />

of interest, places for conversations to<br />

begin. On mantles, they add color and<br />

texture to the stark white of her walls.<br />

Stacked on the floors to improbable<br />

heights, they become statuary or<br />

makeshift tabletops, often adorned<br />

with curiosities and accessories of<br />

their own. If this is hoarding, she<br />

should give lessons.<br />

Past the library lies the kitchen.<br />

Here, amid the appliances and<br />

utensils, Nana Yaa continues to find<br />

opportunities for small narrative<br />

moments. On the counter, a pestle<br />

from Ghana sits beside a jar gifted<br />

from a friend found while traveling<br />

in Mexico. On the walls there are<br />

photos taken by her of designs she<br />

created while studying in London<br />

sitting alongside a fashion illustration<br />

she framed while living in Paris. The<br />

crown jewel of the space is a Ghanaian<br />

mask made by children at a foundation<br />

that her mother once ran in Ghana. To<br />

raise money, Nana Yaa’s mother would<br />

sell the masks in Holland, and she was<br />

able to keep one for herself.<br />

Wherever she goes in the world<br />

and for however long, Nana Yaa takes<br />

Ghana with her.<br />

<br />

aphrochic

issue one

The only place where<br />

Asare-Boadu embraces<br />

maximalism is with her<br />

collection of books.

issue one

Interior Design

It isn’t only an ethnicity, not<br />

only a part of her identity, Ghana<br />

is a family heirloom passed down<br />

to her from her mother and grandmother,<br />

not through explanation, but<br />

by meaningful objects and meaningful<br />

moments. From her grandmother<br />

and great-grandmother,<br />

the designer received a collection<br />

of Kente cloth. As diverse as they are<br />

beautiful, the collection of vintage<br />

fabrics includes instances of pink and<br />

green stripes and elaborate black and<br />

white patterns, as well as the familiar<br />

patterns that are more commonly<br />

collected under the term. From her<br />

mother she inherited her love of<br />

fashion, remembering the stylish<br />

ensembles her mother would create<br />

and her trademark way of matching<br />

her bag to each outfit.<br />

In more concrete terms, Ghana<br />

is a frequent destination of Nana Yaa’s<br />

travels, as she goes often to visit her<br />

mother. True to form however, it isn’t<br />

the bustle and noise of cities that hold<br />

the most interest for her, but the quiet<br />

spaces further north.<br />

“When I go to Ghana I don’t stay<br />

in Accra for long” she offers. “I like to<br />

go up to where my mother’s family is.<br />

I spend a lot of time talking to them,<br />

and I listen.” In those quiet spaces,<br />

Nana Yaa connects to what she feels<br />

are the essential lessons of the place<br />

and the culture, and discovers the<br />

space to let her creativity find new and<br />

ever-more-honest means of expression.<br />

In its most recent incarnation,<br />

her search has transcended both the<br />

verbal and the visual to explore the<br />

kinetic in a unique and mesmerizing<br />

form of performance art.<br />

Nana Yaa is quick to decry any<br />

notion of her performance as dance<br />

or herself as a dancer. While at first<br />

glance it might seem the most natural<br />

categorization, closer inspection<br />

issue one

Interior Design<br />

reveals that it’s nothing so structured<br />

as that - and that’s the point.<br />

Rhythmic and undulating, unintentionally<br />

yet unrepentantly sensual, her<br />

movements eschew formal choreography<br />

in favor of offering her audience<br />

a glimpse of pure emotion in search of<br />

spontaneous and complete catharsis.<br />

The effect is hypnotic, and more than a<br />

few people have fallen under her spell.<br />

As a result, what began as a few posts on<br />

Instagram has expanded into a series of<br />

artistic and commercial collaborations.<br />

<strong>No</strong>tably, Nana Yaa was featured in the<br />

#Like<strong>No</strong>OneElse campaign of Turkish<br />

lingerie line, Else.<br />

Nana Yaa’s home and her<br />

movement work fit well together in<br />

the context of her general approach to<br />

creative things. Unchoreographed, yet<br />

flawlessly executed, her living room<br />

expands from a small entryway at the<br />

top of her stair into high ceilings and<br />

large windows that bathe the room in<br />

sunlight. And like her dancing, Nana<br />

Yaa’s style is minimalist, elegant, and<br />

serene. Taken as a whole, the room<br />

comes together in what feels like a very<br />

classic, French style. Its neutral color<br />

palette seemingly exists to highlight the<br />

rooms undisputed star, the modern,<br />

pink, velvet sofa from Saba Italia. Yet<br />

like so much of Nana Yaa’s decor, the<br />

piece wasn’t a find, it was a gift. A<br />

friend, the company’s owner, simply<br />

felt like she needed a pink sofa.<br />

Themes from the first floor repeat<br />

themselves in larger and interesting<br />

ways on the second. Sculptural stacks<br />

of books and magazines become larger<br />

and more ornate. The walls on every<br />

side of the room are adorned not with<br />

art, but with memories. A framed work<br />

in watercolor turns out to be a doodle,<br />

one of many that a former co-worker<br />

would constantly make and discard.<br />

Vibrant photographs are test<br />

shots for runway shows from years<br />

past. Flea market finds from far-flung<br />

shops adorn the mantle and take the<br />

place of wood in the fireplace. And everywhere<br />

there is evidence of family -<br />

photos with mom, old watches awaiting<br />

repair, and an entire wall dedicated<br />

to images of her grandmother when<br />

she was young. There appears to be<br />

nothing in the space that isn’t personal,<br />

nothing that is without its own specific<br />

meaning, yet it all fits together as if its<br />

only purpose was to be in this room.<br />

Appropriate for a fashion designer,<br />

the only way into the bedroom is<br />

through the closet. A brief hallway<br />

separating the living room from the<br />

bedroom became the perfect space in<br />

which to house the designer’s fashion<br />

arsenal. The bedroom itself is a visual<br />

sanctuary - clean lines and soothing<br />

colors accented by small yet stunning<br />

moments. This is where she keeps<br />

her record collection, and opposite<br />

it, a dress form stands adorned in<br />

a dazzling array of traditional hats<br />

and beaded jewelry, all from Ghana.<br />

Blessed with the same large windows<br />

as the living room, it feels like an easy<br />

room to go into and a hard one to leave.<br />

Nana Yaa’s home is a mirror of<br />

herself. Impeccably presented, but with<br />

a depth of meaning that isn’t hidden,<br />

it just isn’t screaming for attention.<br />

<strong>No</strong>ticing it is inevitable; appreciating it,<br />

unquestionable. But understanding it -<br />

that might take some doing. It isn’t that<br />

her meaning is unfathomable, but that<br />

it requires us to take the time to hear<br />

everything that she’s trying to tell us in<br />

everything that she isn’t saying. It’s a lot<br />

to do in one performance, one visit or<br />

one morning over coffee in Brooklyn -<br />

but that’s ok, she’ll wait. AC<br />

Visit aphrochic.com to see a special performance<br />

by Nana Yaa Asare-Boadu.<br />

<br />

aphrochic

issue one

aphrochic

Food &<br />

Fellowship<br />

Chef Rashad Frazier Is Connecting<br />

Cultures Through Food<br />

It’s a random day. The middle of a hectic week, and Rashad Frazier is<br />

stopping by. The chef, a longtime friend, has a new recipe in mind. We<br />

are willing guinea pigs, eager to see what he wants us to test today.<br />

Photos by Rashad Frazier, Patrick Cline, and Bryan Mason<br />

Words by <strong>AphroChic</strong>: Jeanine Hays & Bryan Mason<br />

issue one

Food<br />

In the past there’s been a karaage<br />

fried chicken sandwich, a slab of<br />

Japanese baby back ribs, even cornmeal<br />

crusted okra. We’re meat-lovers, but<br />

today Rashad’s encouraging us to try<br />

something new. He comes bearing<br />

the most beautiful of gifts. Bags full of<br />

fresh ingredients, aromatic spices, and<br />

fresh shrimp. Before he even begins to<br />

prepare our lunch, we’re ready to give<br />

up red meat (at least for an afternoon).<br />

For Chef Frazier, food is more<br />

than just fuel. It’s a canvas, a history<br />

lesson. And most of all, it’s an opportunity<br />

to connect. The Food Network<br />

star, host of the show Hate It or Plate<br />

It, often uses the phrase “food at play”<br />

when describing his dishes. But when<br />

his food hits the palette, you feel that<br />

there’s something more than play at<br />

work. There’s innovation, meaning,<br />

memory, and a narrative in each bite.<br />

As we sit in our kitchen in Brooklyn,<br />

Rashad cooks comfortably and<br />

we watch in wonder as our stovetop<br />

does things it’s never done before.<br />

We learn as we wait that the dish, a<br />

skillet shrimp, is a recipe from his<br />

food concept, Yoshi Jenkins. On the<br />

surface, Yoshi Jenkins is a combination<br />

of African American and Japanese<br />

<br />

aphrochic

culinary traditions.<br />

An unlikely alliance, one would<br />

think, until you talk to Rashad a little<br />

more. The inspiration for the brand<br />

and its signature fusion of flavors is<br />

rooted in history. Specifically, it references<br />

a brief and extraordinary<br />

period in the 1930s, when Los Angeles’<br />

Little Tokyo district was referred to as<br />

Bronzeville. During that time, Japanese<br />

Americans and African Americans lived<br />

in close proximity before the period of<br />

Japanese internment. Rashad reflected<br />

on this moment in history, wondering<br />

what types of dishes would result from<br />

the two communities living together.<br />

We have no idea what Rashad can<br />

do with a brush and paint, but in a<br />

skillet, he mixes colors like a master.<br />

Bright yellows, reds, and greens mix<br />

together, creating a festive backdrop<br />

for the pops of pink from the shrimp<br />

that are the star of the dish. The<br />

resulting fusion is as subtle as it is<br />

effective. Shrimp are as much a favorite<br />

in Japan as they are in his native <strong>No</strong>rth<br />

Carolina. For this dish he prepares<br />

them in coconut oil and ginger,<br />

longtime staples of traditional Japanese<br />

cooking. At the same time, the cast iron<br />

skillet is reminiscent of the big black<br />

issue one

Food<br />

pot used for the fish fries that are one of<br />

his fondest memories of home.<br />

With Yoshi Jenkins, the dishes span<br />

continents. It takes only a single bite for<br />

the concept to come together. We taste<br />

the American South and understand<br />

Rashad’s stories about fresh tomatoes<br />

in his grandmother’s garden. The<br />

shrimp have the distinctive flavor of the<br />

Far East, notes of ginger and coconut<br />

accented by cilantro and parsley.<br />

The fusion is seamless and complete,<br />

worlds colliding in a single pan.<br />

But this food isn’t just about connecting<br />

distant cultures, or bringing<br />

attention to moments in time long<br />

past. This is food for the here and now,<br />

and for people to enjoy together. <strong>No</strong>t<br />

only do we love the shrimp, sopping<br />

up every last bit with slices of french<br />

bread, we talk, we laugh, and we forget<br />

about everything other than the food in<br />

the bowls and the people in the room.<br />

We end the afternoon as we usually<br />

do, with more talking, more laughing,<br />

and more trips to the skillet. After a<br />

whole day of cooking and eating in<br />

fellowship, we see that food is far<br />

more than fuel. It brings our senses<br />

to life; tells us our stories and those of<br />

countless others, and ultimately it pulls<br />

us together. AC

Yoshi Jenkins Skillet Shrimp<br />

INGREDIENTS<br />

1/4 cup coconut oil<br />

20 jumbo shrimp (about 2 pounds), shelled and deveined<br />

Kosher salt<br />

Freshly ground pepper<br />

4 garlic cloves, thinly sliced<br />

2 tablespoons minced shallots<br />

1 tablespoon minced ginger<br />

4 bird’s eye chilies, seeded, stemmed and chopped<br />

1 cup shellfish stock<br />

4 tablespoons cold unsalted butter, cut into cubes<br />

1 cup heirloom cherry tomatoes, halved<br />

3 tablespoons fresh lemon juice<br />

1/4 cup Italian parsley, chopped<br />

2 tablespoons cilantro, chopped<br />

TOOLS<br />

Large Skillet<br />

Wood Spoon<br />

Spatula<br />

Sharp Knife<br />

Cutting Board<br />

In a large skillet, heat 3 tablespoons of coconut oil. Pat the shrimp dry. Moisture will prevent<br />

shrimp from caramelizing. Season the shrimp with salt and pepper.<br />

Once skillet starts to smoke, add the shrimp to the skillet and cook over moderately high heat<br />

until lightly browned, about 1 to 2 minutes per side. Transfer to a plate.<br />

In the same skillet, heat remaining 1 tablespoon of coconut oil. Add garlic, ginger, shallots, and<br />

chopped chilies and cook over moderately low heat, stirring constantly (this prevents it from<br />

burning), until softened, about 1 minute.<br />

Add the shellfish stock and bring to a boil. Simmer over moderate heat until the broth has<br />

reduced by one-fourth. Whisk in the butter a few cubes at a time until incorporated. Add the<br />

tomatoes and shrimp and simmer until the shrimp are cooked through, about 2 minutes longer.<br />

Stir in the lemon juice, parsley, and cilantro and serve.<br />

Serve with sliced, buttered, and toasted baguette.<br />

Serves 4.<br />

For more about Yoshi Jenkins listen to our One Story Up podcast episode on Food, Culture & Fusion, aphrochic.com.<br />

issue one

Culture<br />

A Day<br />

at the<br />

Beach<br />

Celebrating Sag Harbor with Mr. Baldwin Style<br />

Written and Produced by <strong>AphroChic</strong>:<br />

Jeanine Hays & Bryan Mason<br />

Photos by Brittany Ambridge<br />

Styling by JL Goodman<br />

<br />

aphrochic

58

There are some days that are magic. Days when it all goes right - the perfect<br />

setting, the perfect weather, and the perfect group of friends gathered to mark<br />

an important occasion.<br />

For Donnell and Courtney Baldwin, New York fashion<br />

stylists known for their brand, Mr. Baldwin Style, that<br />

moment came on a sunny day at Havens Beach in Sag<br />

Harbor. The idyllic location, set among bright white sands,<br />

long blades of grass, and even a few deer roaming by the<br />

ocean, was perfect for the couple’s celebration of their<br />

six-year wedding anniversary.<br />

To make the most of a beautiful day, the couple, whose<br />

brand works with Ralph Lauren and Rosario Dawson’s<br />

globally conscious Studio 189, called on an equally fashionable<br />

array of guests to toast their latest milestone in one of<br />

their favorite places to visit.<br />

“We enjoy visiting Sag Harbor during all times of the<br />

year,” says Courtney. The couple was first introduced to<br />

the area when Donnell lived in East Hampton for a short<br />

time. “Each season has its own charm. In the summer, Main<br />

Street is bustling with a mix of residents and weekenders<br />

heading to or coming from the beautiful area beaches. In<br />

the winter, the town is visibly less populated, but equally<br />

charming. Sag Harbor serves as an escape and a place to<br />

recharge year-round. It’s a place where you can go for fresh<br />

air and get a fresh perspective, whether it be for the day or<br />

the entire summer.”<br />

On this day, guests arrived in a steady stream.<br />

issue one

S<br />

b<br />

o

ag Harbor is special to us<br />

ecause it’s a perfect blend<br />

f so many things we love.

Culture<br />

Shoes were quickly discarded in<br />

favor of the feel of sand and surf and<br />

sun on bare feet. Among the guests, a<br />

number of people in the fashion world<br />

came to celebrate the couple’s anniversary.<br />

Fashion designer Jerome<br />

LaMaar arrived in a flowing lilac<br />

kimono, while stylist James Bianca<br />

stunned in an African wax print dress.<br />

Vintage blogger Krystle DeSantos<br />

came in a stylish assortment with a<br />

‘70s vibe. In addition to the fashion<br />

crowd, other creatives were also in attendance,<br />

including interior designer<br />

Mikel Welch from TLC’s Trading<br />

Spaces, and advertiser Law Smithson.<br />

Over the years, Sag Harbor<br />

and its many beaches have seen<br />

countless days like this, when African<br />

Americans gathered to celebrate<br />

moments like these. It’s a history<br />

that begins with freed slaves coming<br />

as laborers in the 19th century, and<br />

later in the 1940s, African Americans<br />

developing safe places of refuge<br />

and leisure. This was particularly<br />

true in the Sag Harbor Hills, where<br />

African Americans have lived in the<br />

beach community since World War<br />

II. During the Jim Crow era, the area<br />

served as a seasonal destination for<br />

affluent and middle class African<br />

Americans. <strong>No</strong>table figures, including<br />

Lena Horne, Harry Belafonte, Duke<br />

Ellington, and Langston Hughes<br />

to name a few, have long come to<br />

Sag Harbor as a summer retreat.<br />

The area’s legacy is so important<br />

to American history that the SANS<br />

neighborhood, named for the historically<br />

Black Sag Harbor Hills, Azurest<br />

and Ninevah areas, was recently<br />

added to the New York State Register<br />

of Historic Places. “When we first<br />

began visiting Sag Harbor, we always<br />

felt a connection to the town, but<br />

had no idea of the history,” remarks<br />

Donnell.<br />

<br />

aphrochic

Culture<br />

For this special day at Havens<br />

Beach, with the historic SANS houses<br />

in the background, guests gathered<br />

for an intimate afternoon soirée.<br />

Donnell and Courtney worked with<br />

John Goodman of JL Goodman Design<br />

to create the perfect look for their<br />

gathering. Sitting firmly in the sand,<br />

with the tide lapping about its legs,<br />

a carved, wooden table looked as if it<br />

had risen magically from the ocean.<br />

Goodman’s design featured a bold mix<br />

of pink, fuchsia and lavender, offering<br />

a bright pop of color against nature’s<br />

palette of green, blue, and sandy<br />

brown. The tablescape, with pampas<br />

grass and fuchsia coral, was a modern<br />

nod to the coastal setting, complete<br />

with beach sand and pebbles dusted<br />

lightly across the surface of the table.<br />

Against the backdrop of sand and<br />

surf, guests toasted the couple while<br />

nibbling on local cheeses, fruits, and<br />

vegetables all from the Hudson Valley.<br />

As Courtney and Donnell<br />

learned about the history of the<br />

place following their first visit, they<br />

began to better understand the connection<br />

that they felt whenever they<br />

were there. Prior to the Civil Rights<br />

Movement, African Americans were<br />

not allowed access to many of the<br />

beaches and entertainment activities<br />

in the area - so we created our<br />

own. For over 40 years, the summer<br />

crowd in Sag Harbor consisted of a<br />

mix of affluent and middle-class Black<br />

people. Doctors, lawyers, educators,<br />

and blue-collar professionals met<br />

each year to escape the racism that<br />

they faced in the world away from<br />

the beach. Meanwhile many of these<br />

families took advantage of the opportunity<br />

to buy beachfront property,<br />

a chance that was scarcely available<br />

elsewhere. Today, many of the homes<br />

in the area have been passed down to<br />

family members and there are still a<br />

<br />

aphrochic

few of the original residents that live<br />

in the coastal communities, helping<br />

to continue the traditions and teach<br />

others about the long-standing importance<br />

of the area.<br />

“There are a lot of places that we<br />

enjoy in Sag Harbor. We love Long<br />

Beach and Havens Beach. Both are<br />

fairly small in size but offer a little<br />

something different. Havens Beach<br />

is adjacent to the historically African<br />

American private beaches,” reflects<br />

Courtney. “From there you have a<br />

great view of the boats and yachts that<br />

come in and out of the town harbor.<br />

Long Beach is beautiful, with areas<br />

of no traditional sand at all, just large<br />

pebbles. It’s just a few minutes drive<br />

from the main village and offers<br />

some of the best views of Sag Harbor’s<br />

amazing sunsets.”<br />

Many things have changed since<br />

Black people first sought out Sag<br />

Harbor in search of the freedom to<br />

enjoy a day at the beach. What hasn’t<br />

changed is the joy of gathering to<br />

celebrate the best parts of life in a<br />

place that requires no explanation,<br />

asks for no apology. For Courtney<br />

and Donnell Baldwin it was the only<br />

place to come to celebrate their life<br />

together, surrounded by friends and<br />

inspired by history. “Sag Harbor is<br />

special to us because it is a perfect<br />

blend of so many things that we love,”<br />

Donnell explains. “Every time we visit,<br />

we learn something either through<br />

experience or conversation that we<br />

can apply to our current business<br />

or that adds to the pursuit of our<br />

wildest dreams. We keep coming back<br />

because of how we feel when we are<br />

there and how refreshed we feel when<br />

we return to our busy and sometimes<br />

hectic life in New York City.” AC<br />

To learn more about Mr. Baldwin Style,<br />

mrbaldwinstyle.com. Visit aphrochic.com to<br />

see more from their day at the beach.<br />

issue one

Culture<br />

Sag Harbor Travel Tips from<br />

Mr. Baldwin Style<br />

WHERE TO EAT<br />

Our favorite restaurant is nothing fancy but has the best seafood! The<br />

Dock House is a favorite of locals and visitors alike and has been our<br />

favorite restaurant since we started coming to Sag Harbor. If we decide<br />

not to eat in the restaurant, we will take our to-go boxes straight to the<br />

beach to enjoy our dinner in perfect view of a beautiful sunset. We also<br />

have a tradition of visiting Buddha Berry, a local frozen yogurt shop that<br />

offers non-dairy soft serve "ice cream," before we head back to the city.<br />

TRAVEL TIPS<br />

You can hop on the Hampton Jitney or into your car and in less than two<br />

hours from Manhattan you can arrive in a sophisticated beach town with<br />

a rich culture that provides an immediate escape and recharge. There’s<br />

no plane or airport hustle required. It’s especially perfect for a romantic<br />

getaway because very little advanced planning is required.<br />

SHOPPING SOURCES<br />

Sag Harbor has intentionally been kept free from large retail chains to<br />

maintain the village charm, so the boutiques that line Main Street are<br />

unique. We love visiting Donna Karan's new Urban Zen store. It’s part<br />

clothing store, part furniture & artifact store, and part restaurant. The<br />

space is truly meditative and peaceful. Upon visiting the store, you are<br />

automatically taken on a journey to Africa and Haiti where many of the<br />

retail items have been made by local artisans.<br />

WHERE TO STAY<br />

We enjoy renting area homes or staying at a local hotel called the Baron's<br />

Cove. The hotel is great in every season, not crowded, and the indoor and<br />

outdoor fireplaces are delightful.<br />

THE HISTORY<br />

<br />

After visiting several times we learned about the rich history of the<br />

area and began looking for ways to connect with the history however<br />

we could. We began reading everything we could find about Sag<br />

Harbor and connected with locals during our visits. It has sparked our<br />

interest in learning more about the history of African American leisure<br />

communities around the country.<br />

aphrochic

Travel<br />

Morocco<br />

A Photographic Journey<br />

The story of Marrakech begins in<br />

the year 475 AH (1062 AD), as two<br />

men walked together in the Sahara<br />

desert. Cousins by blood, brothers<br />

in arms and ideology, they had spent<br />

years at war and were touring the<br />

desert in search of a future.<br />

Photos by Lauren Crew<br />

Words by <strong>AphroChic</strong>: Jeanine Hays & Bryan Mason<br />

<br />

aphrochic

Travel<br />

Abu Bakr ibn Umar, leader of the<br />

Almoravids, and his top lieutenant<br />

Yusuf ibn Tashfin were continuing<br />

a fight begun by Abu Bakr’s brother<br />

Yahya ibn Umar and their teacher, the<br />

Maliki jurist and preacher Abdullah<br />

ibn Yasin. Both had fallen in battle,<br />

leaving it to Abu Bakr and Yusef to<br />

continue to expand their dominion,<br />

and with it their vision of Islam.<br />

Unrivaled in combat, the Almoravids<br />

were unbeaten on the field and<br />

were, at that moment, suffering the<br />

consequences of their success. They<br />

had conquered and occupied Aghmat,<br />

a wealthy and sophisticated city, but<br />

the courtly life of a crowded city was<br />

proving impossible for an army of<br />

hardened desert nomads.<br />

Abu Bakr and Yusef had gone into<br />

the desert seeking a solution - a place<br />

where the Almoravids could build<br />

the type of military encampment<br />

their ranks were used to, defensible<br />

and efficient, with lots of open space.<br />

When they found what they had been<br />

looking for, work on the new encampment<br />

began.<br />

From that time on, the city of<br />

Marrakech has stood for more than<br />

900 years. It has been the capital of<br />

an empire that stretched from present-day<br />

Senegal up through much of<br />

Spain and across most of <strong>No</strong>rth Africa.<br />

It has been a center of learning and<br />

philosophy, a hotbed of sedition, and<br />

the seat of rulers, rebels, and tyrants<br />

alike. It has been besieged, sacked,<br />

restored, colonized, and liberated.<br />

Today, from the Koutoubia<br />

mosque to the Almoravid koubba<br />

(bathhouse), through the maze-like<br />

passages of the souks, to the open<br />

plaza of the Medina, Marrakech - like<br />

all ancient places - carries the weight<br />

of its history. In every moment there<br />

is an almost tangible sense of all that<br />

has come before.<br />

But Marrakech is not simply a<br />

place of the past. Its arts, architecture<br />

and culture continue to touch the<br />

world, influencing everything from<br />

the fashion of Yves Saint-Laurent to<br />

modern interior design. Few places<br />

on earth bridge the gap between the<br />

old world and the new so well. This is<br />

Marrakech, a city in pictures. AC<br />

<br />

aphrochic

Travel<br />

<br />

aphrochic

issue one

Travel<br />

<br />

aphrochic

“Traveling - it gives you<br />

home in a thousand strange<br />

places, then leaves you a<br />

stranger in your own land.”<br />

Ibn Battuta (1304-1369)

Travel

issue one

Reference<br />

The Questions<br />

of Diaspora<br />

It’s hip-hop and street style. It’s Juneteenth in Harlem, the Caribbean Day Parade in<br />

Brooklyn and Carnevale everywhere. It’s all over Beyonce’s latest video. But what is the<br />

African Diaspora? It’s a common term for referring to the collection of cultures across<br />

the world that trace their roots back to the African continent.<br />

But many of us refer to it so often<br />

or hear of it so frequently that we may<br />

not stop to explore precisely what it is<br />

Edwards calls, “a confusing multiplicity<br />

of terms…including ‘exile,’ ‘expatriation,’<br />

‘post-coloniality,’ ‘migrancy,’<br />

‘globality,’ and ‘trans-nationality’<br />

but as so often happens, getting to a<br />

good answer is all about asking the right<br />

questions.<br />

or what it means. In fact, there are many<br />

among others…”<br />

definitions of the African Diaspora,<br />

various constructions describing its<br />

inner workings, and even different perspectives<br />

on the point in time at which it<br />

came into existence.<br />

The difficulty in pinning down a<br />

specific definition for the term might<br />

stem from the fact that it’s even harder<br />

to define what diasporas are in general.<br />

Over the past 50 years, diaspora<br />

has become the favorite answer to a<br />

multitude of theoretical questions and<br />

French sociologist,<br />

Dominique Schnapper, traces<br />

the history differently, asserting that<br />

diaspora has not spawned these terms,<br />

but rather that, “since 1968 it has designated<br />

all forms of population dispersion,<br />

until then evoked by the terms<br />

expelled, expatriate, exile, refugee,<br />

immigrant, or minority.”<br />

So coming to an agreement on the<br />

definition of diaspora is difficult, even<br />

before trying to describe a specific one.<br />

But the level of importance that’s been<br />

The Question of Origins<br />

Diaspora is an ancient term with<br />

a long history. Meaning simply “dispersion,”<br />

or “scattering,” in Greek, the<br />

historian Thucydides was likely the<br />

first to use it to describe the displacement<br />

of people by war. Its association<br />

with dispersed Jewish communities<br />

began with the translation of the<br />

Hebrew Scriptures into Greek between<br />

the 3rd and 2nd centuries, BC. Deuteronomy<br />

28:25 is often referred to specif-<br />

the basis for countless more.<br />

It has<br />

placed on the concept in recent years<br />

ically for its use of the word to describe<br />

given rise to what scholar Brent Hayes<br />

is undeniable. So getting a clear idea of<br />

what diaspora is might be a good idea,<br />

the Jewish nation being “scattered to all<br />

the kingdoms of the earth.” For the next<br />

Words by Bryan Mason

Ngbaka mask, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Yale University Art Gallery

Reference<br />

two millennia, diaspora was used<br />

almost exclusively to refer to dispersed<br />

Jewish populations throughout history.<br />

But by the 20th century other groups<br />

had begun using the word as a designator.<br />

Armenian writers begin focusing<br />

on displacement in their work as early<br />

as 1915, while the African Diaspora<br />

sees its first mention by the late 1960s.<br />

It wasn’t until the early ‘90s that the<br />

explosion of communities regarded<br />

as diaspora began an expansion of the<br />

term. The trend has continued into the<br />

21st century, expanding the application<br />

of the term beyond national dispersions<br />

to include the many groups that inhabit<br />

the concept today.<br />

In 2000, listing the number of<br />

studied diasporas, Khachig Tololyan,<br />

editor of the academic journal Diaspora,<br />

counted “three dozen trans-national<br />

communities…ethnics, exiles, expatriates,<br />

refugees, asylum seekers, labor migrants,<br />

queer communities, domestic service<br />

workers, executives of trans-national corporations,<br />

and trans-national sex workers,”<br />

and the list has grown since then.<br />

The Question of Movement<br />

At the core of every construction<br />

of diaspora is the idea of movement.<br />

All diaspora communities have their<br />

origins in one place and have moved to<br />

several others. The question raised by<br />

identifying so many disparate groups as<br />

diaspora though, is whether all forms of<br />

movement should be thought of as the<br />

same. The key distinction in this debate<br />

is between migration and dispersion.<br />

The primary difference between them is<br />

simple, but significant: volition. Simply<br />

put, the former is something you do, the<br />

latter is something that someone else<br />

does to you.<br />

Dispersion happens in instances<br />

where communities are forced to<br />

move by forces such as war, mass deportation<br />

or, in the case of the African<br />

Diaspora, a massive international slave<br />

trade. Migration, conversely, is largely<br />

a choice. Even in those situations<br />

where lack of employment or resources<br />

cause movement, they don’t force it in<br />

the same way. And while there is unquestionable<br />

trauma in being forced<br />

into migration because of famine or<br />

a weakened economy, it’s a different<br />

trauma than that of surviving a war or<br />

experiencing the Middle Passage.<br />

Translating that distinction to<br />

currently considered diaspora groups,<br />

we see that differences do become<br />

apparent.<br />

The earliest groups to be considered<br />

diaspora, the Jewish, the Greeks,<br />

the Armenians, and the Africans, were<br />

all victims of dispersion of one type or<br />

another. Later groups, such as that of<br />

international sales representatives, or<br />

even Detroit lieutenant governor Garlin<br />

Gilchrist’s laudable Detroit Diaspora<br />

concept, refer to groups that moved of<br />

their own volition. Other characteristics<br />

common to diaspora constructions,<br />

such as a dream of return to the place<br />

of dispersion or the recognition of a<br />

shared culture between members of the<br />

group, may possibly be said to apply, but<br />

certainly not in the same ways.<br />

If there are dispersed communities<br />

that function as diaspora and cannot be<br />

suitably defined by any other term, we<br />

risk losing sight of the unique features<br />

found in those communities by conflating<br />

diaspora with other forms of<br />

movement and migration. This in turn<br />

can lead to misconstrual of the changing<br />

dynamics of diaspora communities and<br />

a misunderstanding of their needs and<br />

goals.<br />

<br />

aphrochic

Spinning By Firelight–The Boyhood of George Washington Gray, Henry Ossawa Tanner, Yale University Art Gallery<br />

In evaluating whether or not certain<br />

communities qualify as diaspora, we must<br />

consider what’s at stake for them in this<br />

categorization, and the extent to which<br />

international salesperson, for example,<br />

I may be dispersed from my homeland,<br />

I may dream of a day of return, I may<br />

even have a tense relationship with the<br />

hostland. But do I have a sense of recognition<br />

with other professionals so<br />

dispersed, even from my own homeland,<br />

to other host lands? Do we recognize in<br />

each other a common struggle or shared<br />

diaspora groups. However it is a very<br />

different conversation for Armenian<br />

or Jewish communities, than it would<br />

be for trans-national executives or<br />

they function as communities. If I’m an<br />

yearnings? Is my dream of return for all of<br />

domestic service workers.<br />

However,<br />

us, or just for myself?<br />

At the same time, reevaluating the<br />

sense of dejection associated with the<br />

loss of the homeland in light of later<br />

prosperity is a common theme for<br />

current frameworks of diaspora make<br />

it difficult to distinguish between them.<br />

The Question of Definitions<br />

Why does diaspora have to have a<br />

issue one

Reference<br />

specific definition that everyone agrees<br />

to? The short answer is: it doesn’t. If<br />

all migrations result in diaspora, then<br />

there can be as many conceptions of<br />

diaspora as there are types of movement<br />

— more even. However, if diasporas are<br />

themselves a unique thing, different in<br />

process and outcome than other types<br />

of migration, it makes sense to study<br />

them as such, especially those groups<br />

for which there’s more at stake than the<br />

designation of being “in diaspora.”<br />

Look at it this way: If one person<br />

believes that a hammer is a building<br />

tool, and another believes it’s a cooking<br />

utensil, they can discuss the importance<br />

of the tool and their love for it all day;<br />

but whether the job is building a house<br />

or baking a cake, they will have a very<br />

difficult time doing it together. They<br />

don’t have to agree on the best ways to<br />

use it, but it would help if they shared a<br />

generally coherent idea of what it is.<br />

The Question of Africa<br />

So what does that mean for us?<br />

Currently there isn’t much that separates<br />

the way that the African Diaspora<br />

is understood from the widely varied<br />

approaches taken in the study of<br />

diasporas as a whole; and for those not<br />

dedicated to studying it specifically, the<br />

African Diaspora is taken to be simply<br />

one more in a field of many. This raises<br />

questions as to whether there are any<br />

unique features of the African Diaspora<br />

that aren’t common to all forms of<br />

migration and that demand specific<br />

attention and study.<br />

This much we know: nearly all<br />

concerned parties agree that those of<br />

African descent who reside in locations<br />

outside of the African continent constitute<br />

a diaspora. However very few<br />

seem to be able to agree on what that<br />

means, or why it is important. Yet these<br />

characteristics do exist, demonstrating<br />

not only the distinctive features of<br />

a diaspora but presenting the African<br />

Diaspora as a unique case for study.<br />

Consider the fact that, unlike other<br />

diasporas, the African Diaspora does not<br />

have a single point of origin. True, we<br />

call it the African Diaspora, but as many<br />

of us are tired of pointing out, Africa is<br />

a continent, not a country. That means<br />

that the story of the African Diaspora<br />

is not a question of dispersal from one<br />

place to several but from many places to<br />

many more. That changes things.<br />

Diasporas are generally about<br />

one culture being scattered to many<br />

places and maintaining relationship to<br />

each other through their shared point<br />

of origin. However each culture of the<br />

African Diaspora is not a scattering<br />

of one culture into many but a fusion<br />

of many cultures into one. In every<br />

instance, dozens of different African<br />

cultures, present in different levels,<br />

came together along with any number of<br />

Native American and European cultures<br />

to become a distinct thing. It became the<br />

African American and the Trinidadian;<br />

it became the Jamaican and the Haitian;<br />

it became Dominican, Cuban, Brazilian,<br />

and more. It became all of us. This significant<br />

difference does not make the<br />

African Diaspora any less a diaspora.<br />

<strong>No</strong>r is it more usefully understood as a<br />

series of smaller diasporas from specific<br />

countries in Africa. It is specifically the<br />

joining of many African cultures, in<br />

unique ways, across a variety of places,<br />

that creates the African Diaspora.<br />

Consider also that the African<br />

Diaspora exists not only as a state<br />

of being, but as a concept. In a short<br />

treatment of the subject, historian Colin<br />

A. Palmer lists five distinct diasporic<br />

<br />

aphrochic

Am I <strong>No</strong>t A Woman & A Sister, Anti-Slavery Hard Times Token, American, Yale University Art Gallery<br />

issue one

Reference<br />

moments in African history, beginning<br />

with the first human migrations out of<br />

the continent. His suggestion being that<br />

the existence of other examples of largescale<br />

movement on the part of African<br />

people means that, “there is no single<br />

diasporic movement or monolithic<br />

diasporic community to be studied.”<br />

While it’s true that the global<br />

migration of Africans predates the<br />

trans-Atlantic slave trade, it’s difficult<br />

and to ignore that the African Diaspora<br />

as a concept is a direct development of<br />

that particular dispersal, and more specifically,<br />

of a long history of thought and<br />

action aimed at dealing with the political,<br />

social, moral, and economic ramifications<br />

of that moment in human history.<br />

And it is on that point that we can begin<br />

to answer some of these questions.<br />

The Question of Purpose<br />

What is the African Diaspora for?<br />

That is the right question. It’s right<br />

because it puts every other question<br />

we’ve asked in perspective. Nearly<br />

every construction of diaspora as a<br />

concept holds that the relationship<br />

between dispersed populations and the<br />

“homeland,” whether real or imagined,<br />

is of vital importance to the category.<br />

Yet few if any consider diaspora from a<br />

functional standpoint.<br />

Perhaps the best way to understand<br />

the African Diaspora is not as a<br />

state of being or a happenstance of historical<br />

migration, but as a tool. The<br />

African Diaspora isn’t simply the result<br />

of voluntary or forced migration from<br />

one continent to several. It is an analytical<br />

structure formed out of a complex set<br />

of ideas created by networks of thinkers,<br />

creatives, groups, and movements<br />

working both in concert and in contravention<br />

to one another over hundreds of years.<br />

Understanding the Diaspora in<br />

this way makes several useful changes<br />

to the way we approach the question<br />

of defining it. First, it argues that the<br />

creation of the Diaspora was not an incidental<br />

consequence of dispersion, but<br />

an intentional decision on the part of<br />

those dispersed.<br />

Second, it requires that the<br />

Diaspora conform to the one criteria<br />

that applies to all tools: that it was<br />

created to do a job. And, like any tool,<br />

understanding the African Diaspora is<br />

in large part a matter of understanding<br />

its process of manufacture and the<br />

reasons for its construction. Once those<br />

are ascertained, we can move on to the<br />

only question that ultimately matters:<br />

Does the African Diaspora still have a job<br />

to do, or is it already obsolete?<br />

This essay is the beginning of a<br />

series that will address this question<br />

by analyzing the African Diaspora from<br />

the perspective of a tool. To do so, it<br />

will trace the historical development<br />

of the African Diaspora concept as an<br />

emergence from the extensive tradition<br />

of international Pan-Africanist thought<br />

that preceded it through the various articulations<br />

of the concept that have influenced<br />

the use of the term today.<br />

This series doesn’t claim to be exhaustive<br />

in its survey of contributors<br />

to Pan-Africanism or to the theory and<br />

study of diaspora. <strong>No</strong>r does it claim to<br />

be authoritative about the nature and<br />

uses of the concept. The goal here is to<br />

begin a conversation, not end one. And<br />

if it inspires us to do more and say more<br />

to explore and strengthen the bonds<br />

between our communities towards<br />

functional and mutually beneficial ends,<br />

then that would be nice too.<br />

The work of Diaspora is not done,<br />

but we can only reach a better understanding<br />

of the potential uses of the<br />

diaspora concept going forward by<br />

more thoroughly understanding the<br />

needs and processes that brought about<br />

its emergence and the purpose for<br />

which we currently need it. AC<br />

<br />

aphrochic

Kente Prestige Cloth, Ghana, Yale University Art Gallery<br />

issue one

PINPOINT<br />

Artists & Artisans | Hot Topic | Who Are You

ARTISTS & ARTISANS<br />

The Cameroonian Juju Hat<br />

An explosion of plumage, pops of bright festive colors, Cameroonian juju hats have spent<br />

the last few years becoming synonymous with global style in home decor. Originally<br />

meant to decorate people, rather than rooms, their popularity has grown to the point<br />

that lately it seems that no room is complete without one of these beautiful feathered<br />

pieces on the walls. Yet, while juju hats are a common sight on the walls of many modern<br />

interiors, for the Bamileke people of Western Cameroon they were once a rare item<br />

reserved only for a select few.<br />

Like most Bamileke art, juju hats<br />

are created specifically for use at royal<br />

festivals or ceremonies. The frame is<br />

constructed from raffia that is woven to<br />

create the support structure. Feathers<br />

taken from a chicken, guinea hen, or<br />

other wild bird are dyed and attached<br />

to the base. A leather strap attached to<br />

the back is used to pull the hat open to<br />

its full breadth. When not in use, the<br />

hat folds up into a manageable bundle<br />

that not only helps with storage, but<br />

also acts to protect the feathers within<br />

the shell of the much tougher raffia<br />

structure. Protecting the delicate<br />

feathers is a high priority, as the hats<br />

play an important societal role.<br />

In Bamileke societies, the king,<br />

called a Fon, is attended by a committee<br />

of eight men known as the Mkem or<br />

“the assembly of holders of hereditary<br />

rights.” Each man of this council<br />

acts as the head of a particular society<br />

tasked with certain duties within the<br />

kingdom. Every two years the Mkem<br />

hold special meetings at which the<br />

wealth of the king is displayed and each<br />

member dons masks appropriate to<br />

their societies. The most venerated of<br />

these, the elephant and leopard masks,<br />

are reserved only for the king and for<br />

members of the Kuosi and the Kemdje,<br />

both warrior societies. It is with these<br />

masks that Tyn or juju hats are most<br />

commonly seen, though occasionally<br />

they are also worn alone, like on the<br />

death of a king or a wealthy member of<br />

one of the eight societies.<br />

One of the biggest questions about<br />

these hats is what to call them. Juju<br />

is not a term found in any Bamileke<br />

language and no one is sure where it<br />

came from. Two theories are that it is<br />

either a derivation of the word “djudju,”<br />

used by the Hausa of northern Nigeria<br />

to denote an evil spirit, or from the<br />

French “joujou,” meaning a trifle or toy.<br />

From the time of its first recorded<br />

use in the late 17th century, juju became<br />

a popular term among Europeans for<br />

referring to West African religions and<br />

their healers who were called juju men.<br />

It may be that an observer mistook the<br />

wearers of these hats for such healers<br />

and applied the name by which we<br />

now know the feathered hats that the<br />

Bamileke call Tyn.<br />

<br />

aphrochic

issue one

HOT TOPIC<br />