AphroChic Magazine: Issue No. 8

This issue is about revolution, remembrance, and rebirth. In Dubai, Chef Alexander Smalls is launching a first-of-its-kind food experience celebrating the culinary revolution taking place in Africa. In New York, as fashion week returned, House of Aama launched a collection remembering the elegance of 20th century Black resort towns. In Philadelphia, Chanae Richards is carving out space for rest, relaxation and meditation. And in Los Angeles, our cover star, Jennah Bell, is part of a renaissance of music that is indie, soulful and written from the heart. In this issue we take you to The Deacon hotel designed by Shannon Maldonado. And in our Wellness section, we let you in our own road to rebirth, through the journey with long-haul COVID that has defined our life this past year. In our Reference section we explore new thoughts on the African Diaspora. Looking beyond the history behind the word to explore the idea itself, opening new worlds of possibility as we begin working to understand what the African Diaspora actually is. And we take you inside the importance of the emerging Black art scene heralded by the Obama portraits which, now well into their national tour, made a memorable stop at the Brooklyn Museum.

This issue is about revolution, remembrance, and rebirth. In Dubai, Chef Alexander Smalls is launching a first-of-its-kind food experience celebrating the culinary revolution taking place in Africa. In New York, as fashion week returned, House of Aama launched a collection remembering the elegance of 20th century Black resort towns. In Philadelphia, Chanae Richards is carving out space for rest, relaxation and meditation. And in Los Angeles, our cover star, Jennah Bell, is part of a renaissance of music that is indie, soulful and written from the heart.

In this issue we take you to The Deacon hotel designed by Shannon Maldonado. And in our Wellness section, we let you in our own road to rebirth, through the journey with long-haul COVID that has defined our life this past year.

In our Reference section we explore new thoughts on the African Diaspora. Looking beyond the history behind the word to explore the idea itself, opening new worlds of possibility as we begin working to understand what the African Diaspora actually is. And we take you inside the importance of the emerging Black art scene heralded by the Obama portraits which, now well into their national tour, made a memorable stop at the Brooklyn Museum.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

APHROCHIC<br />

a curated lifestyle magazine<br />

ISSUE NO. 8 \ FALL/WINTER 2021<br />

DESIGNING COMFORT \ BACK TO LIFE \ THE WORK OF PEN AND GUITAR<br />

APHROCHIC.COM

APHROCHIC INTERIORS<br />

BOOK A PERSONAL DESIGN CONSULTATION<br />

@APHROCHIC ON FACEBOOK

Well, it was no 2020, but 2021 has still been a long year. For many of us it’s felt like<br />

several years wrapped up in one. We began the 21st year of the 21st century with<br />

great hope. The whole world waited with bated breath for a vaccine to change the<br />

world that COVID had created. When it arrived, for a time, there was a feeling that<br />

life would return to normal. But then suddenly there was vaccine hesitancy, and the<br />

Delta variant, and more that we never predicted.<br />

Cities began returning to life, some slowly, some recklessly. But things were different. Life in quarantine<br />

meant time to think, and many of us are looking at things a bit differently now. Slowly the realization is dawning<br />

that the world has not returned back to normal at all, and maybe that’s a good thing. A global pandemic changes<br />

everything. COVID-19 has changed our world in some truly complex ways. But as this long year marches on, we’re<br />

beginning to see something new take root. A new world is emerging - and we all have a part to play in shaping it.<br />

As 2021 is ending, we’re thinking ahead about this new world that we are entering and those who are at the<br />

forefront: the artists, designers, musicians, fashion savants, chefs and more who are charting a new creative<br />

path. And in this issue we’re going around the world to visit some of our favorites, and explore some exciting new<br />

fronts. Like 2021, this issue is about revolution, remembrance, and rebirth.<br />

In Dubai, Chef Alexander Smalls is launching a first-of-its-kind food experience celebrating the culinary<br />

revolution taking place in Africa. In New York, as Fashion Week returned, House of Aama launched a collection<br />

remembering the elegance of 20th century Black resort towns. In Philadelphia, Chanae Richards is carving out<br />

space for rest, relaxation, and meditation. And in Los Angeles, our cover star, Jennah Bell, is part of a renaissance<br />

of music that is indie, soulful, and written from the heart.<br />

In this issue we take you to The Deacon hotel designed by Shannon Maldonado. And in our Wellness section, we let<br />

you in on our own road to rebirth, through the journey with long-haul COVID that has defined our lives this past year.<br />

In our Reference section, we explore new thoughts on the African Diaspora. Looking beyond the history and<br />

behind the word to explore the idea itself, opening new worlds of possibility as we begin working to understand<br />

what the African Diaspora actually is. And we take you inside the importance of the emerging Black art scene<br />

heralded by the Obama portraits which, now well into their national tour, made a memorable stop at the Brooklyn<br />

Museum.<br />

2021 has been a long year. The world is re-emerging, and the work being done by Black creatives today is<br />

setting the stage for a bright new future ahead.<br />

Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Founders, <strong>AphroChic</strong><br />

Instagram: @aphrochic<br />

editors’ letter

FALL/WINTER 2021<br />

DEPARTMENTS<br />

Read This 10<br />

Watch List 12<br />

The Black Family Home 14<br />

Mood 22<br />

FEATURES<br />

Fashion // House of Aama 26<br />

Interior Design // Chanae Richards: Home Again 38<br />

Culture // The Creator's Dinner 56<br />

Food // Alkebulan 62<br />

Travel // A Place to Gather 74<br />

Wellness // Back to Life 82<br />

Reference // The Structure of Diaspora 94<br />

Sounds // Jennah Bell 100<br />

PINPOINT<br />

Artists & Artisans 108<br />

Hot Topic 114<br />

Who Are You? 120

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

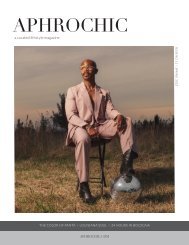

Cover Photo: Jennah Bell<br />

Photographer: Mallory Talty<br />

Publishers/Editors: Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Creative Director: Cheminne Taylor-Smith<br />

Editorial/Product Contact:<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong><br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong>.com<br />

magazine@aphrochic.com<br />

Sales Contact:<br />

Ruby Brown<br />

ruby@aphrochic.com<br />

Contributors (left to right below):<br />

Patrick Cline<br />

Chinasa Cooper<br />

issue eight 9

READ THIS<br />

This month our book selections focus on Black women, a group often overlooked, mischaracterized,<br />

and uniquely facing racism and sexism at the same time. New research by the American Psychological<br />

Association coined the term ‘intersectional invisibility,' shining a spotlight on the need for more visibility<br />

for Black women in media. These three books deliver on that need. The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois focuses<br />

on a long line of Black women from one Georgia family and the lessons they pass down to one daughter,<br />

Ailey Pearl Garfield, as she straddles her lives in the <strong>No</strong>rth and the South. Three Girls from Bronzeville is<br />

a memoir about three women who grow up together in the South Side neighborhood of Chicago. It's both<br />

a celebration of sisterhood and friendship and a testimony to the unique struggles of Black women. Black<br />

Girls Must Die Exhausted focuses on a woman who seems to have it all, until a major setback causes her to<br />

reexamine her life and her friendships. All three books create a much-needed visibility for Black women.<br />

Three Girls from Bronzeville<br />

by Dawn Turner<br />

Publisher: Simon & Schuster. $22.99<br />

The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois<br />

by Honoree Fanonne Jeffers<br />

Publisher: Harper. $18.99<br />

Black Girls Must<br />

Die Exhausted<br />

by Jayne Allen<br />

Publisher: Harper<br />

Perennial. $29.99<br />

10 aphrochic

WATCH LIST<br />

When the Metropolitan Transportation Authority decided to demolish and rebuild the Third Avenue<br />

Bridge in Mount Vernon, NY, they still wanted to retain the history that the 121-year-old bridge had of<br />

connecting a community. And they wanted the bridge to also represent that community in a new way.<br />

So the MTA and the city of Mount Vernon commissioned artist Damien Davis to create a series of panels<br />

spanning the bridge to tell the visual story of Mount Vernon. The work, entitled Empirical Evidence, was<br />

created with painted water-jet cut aluminum, and it is meant to question "how cultures code and decode<br />

representations of Blackness and Black people." The panels invite interaction and discussion about what<br />

each symbol of Blackness means and how those definitions change over time. Davis said his inspiration<br />

was language itself and how it works as a bridge, and the symbols he created are also a language of their<br />

own. "For me, the question becomes how we take these larger complicated ideas, that can be hard to<br />

explain, break them down into simple shapes, and then allow new dynamic, complicated conversations<br />

to form around them. That is my hope for this project."<br />

Empirical Evidence<br />

by Damien Davis<br />

Mount Vernon 3rd Avenue Bridge<br />

12 aphrochic<br />

serenaandlily.com

THE BLACK FAMILY HOME<br />

Designing Comfort<br />

Bedrooms need to be healthy spaces. They need to be restorative.<br />

And for many in the Black community, they need to truly be places<br />

of rest. Spaces where we can retreat from the world, get a full night’s<br />

uninterrupted sleep, so that we can get up tomorrow and continue our<br />

fight for a better world. As we embarked on creating the bedrooms of<br />

our dreams in our very first house, we worked to answer the question<br />

- how do we design comfort?<br />

We worked in partnership with<br />

Article to find the perfect pieces for the<br />

main and guest bedroom in the house, and<br />

had a conversation with the brand about<br />

how we approach designing spaces of<br />

comfort for our home.<br />

Article: How do you make a bedroom<br />

feel comfortable and cozy?<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong>: The average person<br />

spends 1/3 of their life in bed. This means<br />

we are likely to spend a lot of our time<br />

in our bedrooms. These spaces need to<br />

support us while we sleep and first thing<br />

when we wake up. To make sure this space<br />

is comfortable and cozy we begin by identifying<br />

the perfect bed.<br />

When searching for that perfect bed,<br />

we like to ask a few questions: do you want<br />

to be up high, or do you like something<br />

low and modern? Do you want a bed that<br />

requires a box spring or would you rather<br />

go with a simple and streamlined bed that<br />

just requires a mattress? Do you want a<br />

bed that’s made with natural materials<br />

that promotes a healthier lifestyle?<br />

Once we can answer all of those<br />

questions and find the perfect bed, then it’s<br />

about the pieces needed to complete the<br />

room that add that extra sense of comfort.<br />

You want bedside tables where you can<br />

have books and lighting, and maybe even<br />

a carafe of water if you’d like to have a sip<br />

of water in the evening. It’s nice to include<br />

a cozy bench at the end of the bed. It’s a<br />

useful piece of extra seating in the room.<br />

You want to be sure that everything you<br />

need is included in the design of the<br />

bedroom. And most importantly, that you<br />

love your bed!<br />

AR: How do you incorporate your<br />

personal style into the bedroom?<br />

AC: That personal style begins with<br />

bedroom furniture. You can go modern,<br />

classic, wood, upholstered. There’s so<br />

many different types of aesthetics to<br />

choose from. For these bedrooms we went<br />

The Black Family Home is an<br />

ongoing series focusing on the<br />

history and future of what home<br />

means for Black families.<br />

Stay tuned for the upcoming book<br />

from Penguin Random House.<br />

Photos by Bryan Mason<br />

Jeanine in the<br />

Celeste Kaftan,<br />

see page 23<br />

14 aphrochic

THE BLACK FAMILY HOME<br />

mid-century modern. It felt right for the<br />

house, which is a farmhouse. We wanted to<br />

showcase the beauty of natural wood, and<br />

we are able to do that with these gorgeous<br />

pieces from Article.<br />

Then it’s all about pieces that complement<br />

that mid-century look and our<br />

own aesthetic. We love being able to incorporate<br />

art and artisan pieces in the<br />

bedroom, particularly by artists of the<br />

African Diaspora. So we included sculptural<br />

pieces in this room, some that have<br />

been handmade by Black designers. The<br />

personal touches make the room feel so<br />

warm and it reflects our cultural heritage.<br />

AR: While incorporating that style how<br />

do you distinguish between two bedrooms,<br />

do you like to make those spaces cohesive,<br />

complementary, or contrasting?<br />

AC: This is such a good question.<br />

We actually begin with an entire style<br />

for the house. In this home, there’s a lot<br />

of beautiful woods that really make the<br />

farmhouse style come to life. The love of<br />

wood was extended into both the main and<br />

guest bedroom as well, with a shaker-style<br />

bed for the guest bedroom and a 1950s style<br />

platform bed for the main bedroom. But<br />

while wood was a commonality, to give<br />

each room its own personality, we chose<br />

different finishes. In the guest room, the<br />

black ash stain feels fresh and modern.<br />

And in the main bedroom, the walnut<br />

warms things up immediately.<br />

AR: What are some of your favorite<br />

qualities or features in your Article<br />

bedroom furniture? How do they contribute<br />

to the feel you want for the bedroom?<br />

AC: We live in a 1930s farmhouse in<br />

upstate New York. This home was beautifully<br />

built and it has a heritage to it. It’s<br />

important to us to honor that, and we<br />

wanted to bring in high-quality pieces<br />

that shine in every room in this house. We<br />

have incorporated some beautiful pieces<br />

from Article into our design projects over<br />

the years, and we know that pieces from<br />

Article are made with quality in mind.<br />

And it’s no different with the bedroom<br />

furniture. These are beautifully crafted<br />

bedroom furnishings that are built to last.<br />

They are also pieces that fit with our<br />

lifestyle. We love that the Nera Walnut King<br />

Bed comes with nightstands with wirenooks,<br />

so that we can charge our phones at<br />

night. And soft-close nightstand drawers<br />

mean no disturbances in the middle of the<br />

night. That is good design and ultimately<br />

it makes for a beautiful bedroom that you<br />

can rest and relax in. We moved upstate to<br />

create a calming retreat for ourselves and<br />

these pieces from Article absolutely contribute<br />

to that. AC<br />

Guest Bedroom Selections: Lenia Black Ash Queen Bed $1099, Lenia Black Ash 2 Drawer Night Stand $399,<br />

Gabriola Ivory Boucle Bench $379<br />

16 aphrochic issue eight 17

THE BLACK FAMILY HOME<br />

18 aphrochic issue eight 19

THE BLACK FAMILY HOME<br />

Main Bedroom Selections: Nera Walnut King Bed with Nightstands $1499, Nera Walnut 6 Drawer Low Double<br />

Dresser $1349, Chanel Volcanic Gray 56” Bench $349, Candra Oak Media Unit $899.<br />

20 aphrochic issue eight 21

MOOD<br />

RETURN TO LIFE<br />

It’s time for a new normal. One where health, wellness, and<br />

comfort come first. This season is all about a return to<br />

living safely, and these pieces from Nike will help you do<br />

just that. The latest collection includes hi-tech, sustain-<br />

Nike Therma-FIT<br />

Repel Women’s<br />

Synthetic-Fill<br />

Golf Jacket $160<br />

Nike Sportswear<br />

Club Men’s<br />

Tie-Dye French<br />

Terry Crew $75<br />

Nike Sportswear<br />

Tech Pack<br />

Women’s Pants<br />

$100<br />

able fashions made from recyclable and organic materials.<br />

These thoughtfully designed sportswear pieces will keep<br />

you warm, comfortable, and looking right for the life you<br />

want. It’s fashion-forward clothing that’s perfect whether<br />

you’re working at home, working out at home or stepping<br />

out — masked up — for some outdoor fun. Our favorite items<br />

from Nike can be mixed or matched for a complete capsule<br />

collection of comfortable staples that will support you as<br />

you embrace living again.<br />

Nike Heritage 2.0 Small Items Bag $30<br />

See more at Nike.com.<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong> is partnering<br />

with Nike to identify ways<br />

to safely return to life. See<br />

how Jeanine and Bryan<br />

style their own Nike capsule<br />

collection @aphrochic on<br />

Instagram.<br />

Nike x sacai<br />

Women’s Skirt<br />

$500<br />

Nike Daybreak<br />

Women’s Shoes<br />

$100<br />

Nike Swoosh<br />

Luxe Bra $60<br />

Nike Yoga<br />

Dri-FIT<br />

Men’s<br />

Pants $80<br />

Nike Manoa<br />

Men’s Boot $85<br />

Nike<br />

Sportswear<br />

Tech Fleece<br />

Men’s Full-<br />

Zip Hoodie<br />

$140<br />

22 aphrochic issue eight 23

FEATURES<br />

House of Aama | Home Again | The Creator's Dinner | Alkebulan |<br />

A Place to Gather | Back to Life | The Structure of Diaspora | The Work<br />

of Pen and Guitar

Fashion<br />

House of Aama<br />

Fashion Beyond the Gaze<br />

White gaze has been a part of the African American<br />

experience from the very beginnings of the culture. It<br />

began with the traders, the owners, and overseers. As<br />

we’ve grown, it’s grown with us, judging and stereotyping,<br />

prescribing, oversimplifying — and more often than not,<br />

outright lying — demanding a response, even when the<br />

response is overt and intentional disregard. Even today,<br />

when we so often place ourselves consciously beyond this<br />

gaze, it is still there to be transcended. But white gaze<br />

isn’t ubiquitous. There are quite a few times in our history<br />

when it hasn’t been there. And when those moments came,<br />

it was like a day at the beach. Thankfully, LA-based fashion<br />

house, House of Aama is here to take us back.<br />

Words by Bryan Mason<br />

Photos by JD Barnes<br />

26 aphrochic

issue eight 29

Fashion<br />

Headed by the mother/daughter design team of<br />

Rebecca Henry and Akua Shabaka, House of Aama seeks to<br />

probe and explore the many sides of the Black experience<br />

in America and all over the world, presenting its pieces as<br />

acts of spirituality as much as feats of design. The subject<br />

of the brand’s first New York Fashion Week event, a Spring/<br />

Summer ready to wear collection for 2022, evokes the<br />

feeling and style of America’s Black beaches.<br />

In 1893, Charles Douglass — the youngest son of<br />

Frederick — and his wife Laura were refused entry to a<br />

restaurant in Chesapeake Bay. The couple responded<br />

by purchasing 40 acres of land and founding Highland<br />

Beach, the first Black beach resort, some 35 miles east<br />

of Washington DC. Douglass also sold portions of the<br />

land to friends and family, a long list of which included<br />

such notables as U.S. Senator Blanche K. Bruce, Virginia<br />

Congressman John Mercer Langston, Louisiana Governor<br />

P.B.S. Pinchback, and Judge Robert and Mary Church<br />

Terrell. The resort was hugely popular, incorporating itself<br />

as a town in 1922 under Charles Douglass’ son, Haley. The<br />

practice quickly caught on and more Black resort towns<br />

began springing up along the east coast such as Oak Bluffs<br />

in Martha’s Vineyard, Carr’s and Sparrow’s Beaches in<br />

Maryland and several beaches in Sag Harbor (see <strong>Issue</strong> #1).<br />

Titled “Salt Water,” in honor of those who survived<br />

the Middle Passage, House of Aama’s beach collection is a<br />

fond look back on those beaches, what they meant to Black<br />

people then and what they mean to us now. It’s also a tribute<br />

to Okolun, Agwe, and Yemaya, water spirits connected to<br />

traditions found throughout the Diaspora. Boasting a variety<br />

of looks, from form-fitting and flowing dresses to jumpsuits<br />

and bikinis, this collection not only offers us all a chance to<br />

hit the beach looking fierce, it reminds us that we always did.<br />

To launch the collection at fashion week House of Aama<br />

invited guests to “Camp Aama,” a fictionalized remembrance<br />

of a Black resort town located in the Freehand Hotel in New<br />

York City. There, mother and daughter showed off the many<br />

layers of their design aesthetic including their variety of<br />

illustrations, fabrics, and prints, all created in house by their<br />

design team in LA.<br />

Combining historical research and oral tradition with<br />

a sharp eye for celebrating days past in modern garments,<br />

House of Aama’s Salt Water collection is fashion in its highest<br />

form — an act of society rather than a simple adornment of it.<br />

By reminding us once again that we have never been passive<br />

observers in our own story, Salt Water seeks to inspire<br />

conversations on the present and future even as it sheds light<br />

on the corners of our past we don’t often see commemorated.<br />

It’s a reminder that regardless of how long the gaze has been<br />

with us, it’s never been a part of us. AC<br />

30 aphrochic

Fashion<br />

32 aphrochic issue eight 33

issue eight 35

Fashion<br />

Global Attic • 312•767•4928 • Chicago<br />

www.globalattic.com<br />

36 aphrochic issue eight 37

Interior Design<br />

Chanae<br />

Richards:<br />

Home Again<br />

Home isn’t always where you think it should be. Sometimes the<br />

twists and turns of life take you back to a place you’ve already<br />

been, but didn’t quite recognize the first time around. Where it<br />

goes from there is anyone’s guess, but there’s a good chance it<br />

won’t be anything you expected. That’s the way it was for interior<br />

designer, Chanae Richards, and the home in Philadelphia that<br />

she had to leave to love.<br />

Words by Bryan Mason<br />

Photos by Chinasa Cooper<br />

38 aphrochic

Interior Design

Interior Design

Interior Design<br />

The founder and creative director of Oloro Interiors,<br />

Chanae was only 22 years old the first time she set foot in her<br />

house, and just a short time away from graduating from Temple<br />

University with a BS in criminology. Built in the 1960s, in a style<br />

that is much older, the Philadelphia row home had seen its<br />

share of hard times — and things had not improved much since<br />

then. “It was awful,” Chanae remembers. “There had been a fire<br />

years before. Then someone got ahold of it at a sheriff sale. They<br />

flipped it and sold it to me, but they did extremely shoddy work.”<br />

Leaking pipes, unstable flooring, and an ancient boiler all<br />

proved challenges for the young homeowner in her first year. “I<br />

also learned you should always hire your own home inspector,”<br />

she advises. Ultimately, buying the house had been a good idea,<br />

even though it wasn’t exactly hers.<br />

“I’m a Bronx girl,” she offers proudly. And though Philadelphia<br />

had been her city of choice for an education, she‘d<br />

never had any intentions of staying. “I knew that I was going<br />

back home to the Bronx after graduation, because that's what<br />

you do,” she says. “You graduate, then you go back home.” But<br />

a mentor of hers had other ideas. She persuaded Chanae to<br />

check out some homes in the Germantown area of the city. “I<br />

didn’t know anything about Germantown,” she laughs. "But<br />

before I knew it, I was looking at houses with her realtor before<br />

I graduated.”<br />

Chanae’s home is designed to be a place of comfort. Its<br />

island-inspired minimalism, juxtaposing moments of color<br />

with an abundance of open space, is at once a testament to her<br />

Caribbean roots — “My parents immigrated from Jamaica in<br />

the '70s,” she explains — and to what she wants from her life in<br />

this home. To that point, her front door opens into a spacious<br />

sun room. A traditional staple of Philadelphia row homes, the<br />

room is dominated by a single, wall-length window designed<br />

to catch every moment of sun. Chanae has decorated with soft<br />

blue curtains against bright, white walls, and a modern lighting<br />

pendant. Opposite the door, the room’s lone piece of furniture<br />

sits against the far wall. A vase of limelight hydrangeas and a<br />

low-hung artwork complete the vignette, while the bench sits<br />

waiting for coats, keys, and anything Chanae needs to leave at<br />

the door when she gets home.<br />

By her own report, Chanae’s home buying experience<br />

was generally painless — a fortunate exception to the rule that<br />

makes buying a home a hassle for most everyone, but especially<br />

difficult for people of color. “It was so smooth,” she marvels. “I<br />

didn't even realize that we’d had dinner with her realtor a couple<br />

of times. And now I'm filling out loan applications in my senior<br />

year. So after I graduated I moved from the dorm and straight<br />

to this house.”<br />

While the buying process might have been quick and easy,<br />

getting settled was anything but. Repairs were just the start of it.<br />

“It was a huge transition because I’m a first-time homeowner,<br />

and I'm 22,” she says, “and I have this whole house, but I don't<br />

have any furniture, I don't have a place to sleep.” So though<br />

it may have taken only a few months to get the house, shaping<br />

it into a home was a process for the first couple of years. But<br />

hardship builds character, and in Chanae’s case, the struggle of<br />

getting her place into shape was where her new direction would<br />

start — it would just be years before she realized it.<br />

“It took a long time to get the pieces that I wanted and<br />

needed,” she remembers. “I didn’t have any money so I<br />

developed this philosophy of only buying the pieces that I loved,<br />

44 aphrochic

Interior Design<br />

because the things that you only like are not going to last.” It’s a<br />

perspective that has served her well ever since — even if it does<br />

take a while to sit back and enjoy the results. “I didn't get in a bed<br />

for maybe the first four months of living here,” she laughs.<br />

Three years after moving into her home, Chanae found<br />

herself heading back to New York. “Family obligation,” she<br />

shrugs. For the next 10 years, the home was occupied by a<br />

succession of tenants, while Chanae’s life and career path<br />

continued on in New York.<br />

That path had already undergone its first big shift even<br />

before she returned to the Bronx. While pursuing her grad<br />

degree and career in criminal justice, a rotation in cybercrime<br />

introduced her to the world of finance. “And I realize, wow, I<br />

really like numbers,” she marvels. “I really like analyzing bank<br />

records. So I left and got a second master's degree in Public Administration<br />

with a concentration in finance.” That change led<br />

to a series of financial posts for charter schools, non-profit<br />

organizations and NYU — and a similar progression of apartments.<br />

“My last full-time New York apartment was in Harlem.<br />

I still live there part time,” she explains. “And it's great. It gives<br />

you all the New York vibes. But it's not mine.”<br />

While even the poshest New York apartments are known<br />

for their tight confines, Chanae’s Philadelphia home offers far<br />

more space, and her design appreciates it. The vacation vibe of<br />

the sun room flows effortlessly into the living room. The walls<br />

and curtains lead the way, maintaining their color from the<br />

previous space. Pops of color remain few but meaningful, a<br />

combination of art, furniture and plants. Textures largely take<br />

the place of colors here, giving depth and interest to the nearly<br />

colorblocked room. The rug takes center stage, alternating<br />

heights and textures in a distractingly engaging design. The side<br />

table, mantle and even the radiator add to the story, blending<br />

modern design looks with the house’s beautiful old bones.<br />

A similar rug adds slightly more color to the slightly more<br />

colorful dining room. Like the living and sun rooms, this space<br />

prioritizes giving Chanae room to breathe by concentrating the<br />

intimate dining setting at the center of the room. The space is<br />

defined by patterns and colors as the geometric plank arrangement<br />

of the hardwood floor plays with the similar colors and<br />

dissimilar pattern of the rug. Around the table, a mismatched<br />

arrangement of chairs offers a variety of patterns and colors.<br />

And on the walls, the distinct lines of one painting in bright<br />

reds, blues and whites sits directly across from the blurred<br />

lines of another in muted pastels. It’s a subtle yet sophisticated<br />

interplay that makes the long road to her design career seem<br />

like a forgone conclusion.<br />

Much like pursuing dreams of a career in law enforcement<br />

led to finance, it was finance that led Chanae to a life in design.<br />

“A photographer friend asked me to stage a gallery for him in<br />

the Lower East Side. And then his friends started asking me to<br />

do it.” The constant requests started Chanae thinking about a<br />

career change, though she was dubious at first — especially<br />

when she found out that they were willing to pay. “I was like,<br />

‘you'll give me money to just curate your art,’” she reminisces.<br />

“And they’re like, ‘Yeah.”<br />

After a year of double duty, working full time and<br />

hammering out a business plan, Chanae was ready for a change<br />

— just about. “I quit my job on January 12, 2018,” she muses,<br />

"then took a one way trip to Italy.” Figuring that it could be her<br />

last vacation for a while, Chanae was determined to make the<br />

most of it while making firm decisions about her next step.<br />

When she returned, she made the transition into full time production<br />

design.<br />

Chanae’s guest room looks like a space styled for one of<br />

her shoots. The explosion of plants covers the room from end<br />

to end, and where there aren’t plants, there’s plant-themed<br />

wallpaper to make the point even clearer. But this room isn’t<br />

staged for a commercial, and it’s not just a guest room. It’s<br />

home for the one element of home decor that escapes Chanae’s<br />

refined, minimalist style.<br />

“So, I'm that girl on the plane with plants in her bag,” she<br />

giggles. “There’s some in that room that I brought back from<br />

a trip to California, a philodendron I brought back up as carry<br />

on from a trip to South Carolina to see my grandmother and a<br />

whole banana plant.” The list doesn’t end there. Other plants<br />

hail from DC or New York. “And a fiddle leaf fig from one of<br />

46 aphrochic

Interior Design<br />

48 aphrochic

Interior Design<br />

my girls that I took from her because she was<br />

gonna kill it,” she laughs.<br />

Chanae’s new career in her old city was<br />

going strong. But then something changed.<br />

“I love my place in New York,” she confesses,<br />

“But there’s something different about coming<br />

home to a place you own.” Despite its bumpy<br />

start and long periods of absence, owning<br />

her own home always had a special meaning<br />

for her. “I'm one of the first individuals in my<br />

family to buy a house,” she explains. “So it<br />

means a lot to have this in my life.”<br />

One of eight siblings, Chanae grew up<br />

in apartments until her parents purchased<br />

a home in her first year of high school. “That<br />

was the first time anyone in my whole family<br />

ever bought a house,” she says. “And I became<br />

the next person to have one. So it's more than<br />

a dream.”<br />

The same year that Chanae left her job,<br />

her last tenant moved out of the house. And<br />

while the loss of income wasn’t welcome, it did<br />

provide her with a new opportunity. “When<br />

that tenant moved out the plan was to just to<br />

renovate it and rent it to someone else,” she<br />

recalls. “But in that process, I started to realize<br />

how beautiful it was. I started feeling the bones<br />

and feeling the neighborhood. And it dawned<br />

on me that I really like it here.”<br />

If the first floor of Chanae‘s home is a<br />

lesson in refined minimalism, the upstairs<br />

is where she starts to have some fun. Where<br />

the guest room is a study in plant design, her<br />

master bedroom is full of color and life, from<br />

the jewel toned walls to the vibrantly patterned<br />

rug. Just past the foot of the bed a massive<br />

fiddle leaf fig sits next to an x-bench piled high<br />

with fuchsia pillows. And against the far wall, a<br />

solitary chair is outlined against a feature wall<br />

highlighted by an active floral wallpaper and<br />

the triangle arch at its top. It provides a completely<br />

different aesthetic from the rest of the<br />

house while keeping with the overall feel of a<br />

spacious vacation home in the city.<br />

Since starting her life as a designer<br />

and restarting her life as a Philadelphian,<br />

Chanae has found herself becoming more at<br />

home with her new path. Along the way she’s<br />

forged new alliances, finding community<br />

in her chosen industry. “It took a while,” she<br />

admits, “but I've managed to connect with<br />

other designers who look like me and sound<br />

like me, who do their own thing.” She’s also<br />

fallen deeper in love with Germantown, a<br />

historic neighborhood that has been predominantly<br />

Black since the height of the Great<br />

Migration. She’s also become an important<br />

part of the Philadelphia business community.<br />

As the Managing Director of the Philadelphia<br />

Housing Authority’s Entrepreneurial<br />

Resource Center, Chanae leads a team<br />

of innovators working to provide business<br />

resources and entrepreneurial support specifically<br />

to those living in Philadelphia’s public<br />

housing.<br />

For Chanae Richards, life after collegestarted<br />

with buying a house. And though she<br />

didn’t realize it at the time, it started her on a<br />

path that led from the life she’d planned for<br />

to something she’d never imagined. It wasn’t<br />

easy at first. “I left this six figure job to figure<br />

out something else where I had no experience.<br />

I won't lie and say, it’s been all peaches<br />

and cream,” she says. “I have cried. But I’ve also<br />

learned." AC<br />

50 aphrochic

Culture<br />

The<br />

Creator’s<br />

Dinner<br />

Creatives Gathered at The Gallery<br />

Bar at Neuehouse in New York City<br />

to Celebrate Designer Mark Grattan<br />

As New York City re-emerges from the pandemic,<br />

events and gatherings are being held again. It’s<br />

a time of rebirth for one of the world’s cultural<br />

centers, and a time to celebrate those who are<br />

pushing culture forward.<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays<br />

Photographs by Leandro Justen, courtesy of Neuehouse Madison Square<br />

56 aphrochic issue eight 57

Culture<br />

Designer Mark Grattan is one of those people. The designer is at<br />

the forefront of modern furniture design. Together, with his partner<br />

Adam Caplowe, the two have developed VIDIVIXI, a brand that creates<br />

coveted bespoke objects in their studio in Mexico City — from their<br />

HermanX Auxilliary Table with an interlocking square base structure,<br />

to their On Second Thought Club Chair where panels of leather run to<br />

create a unique curved form.<br />

Grattan recently won Ellen’s Next Designer and is now part of<br />

Saint Heron's group of multi-disciplinary creatives to lead product<br />

development. This summer a group of New York City’s design and<br />

community gathered to celebrate Grattan’s many accomplishments.<br />

Hosted by Tiana Webb Evans of ESP Group and Yard Concept,<br />

Grattan was feted by friends and colleagues including, architect<br />

Felix Burrichter, curator Alexandra Cunningham Cameron, lighting<br />

designer Gabriel Hendifar, music artist Solange Knowles, artist<br />

Fernando Mastrangelo, interior designer Chloe Pollack-Robbins,<br />

author Doreen St. Felix, curator Danny Dunson, Ryan Towns, and the<br />

editor-in-chief of Elle Decor, Asad Syrkett.<br />

Held at Neuehouse Madison Square the evening could not have<br />

been more perfect, held inside the social club’s new space, The Gallery<br />

Bar. Recently opened in September, The Gallery Bar was designed to<br />

be a day-to-night environment supporting creativity, innovation,<br />

collaboration and connection through food and drink. Over beautifully<br />

veined marble tables, guests sat together on intimate banquette<br />

seating, toasting over a curated menu of speciality cocktails and global<br />

and sustainable food.<br />

"Tonight's dinner is an elegant and exciting first look preview of our<br />

new Gallery Bar at NeueHouse NYC," said Josh Wyatt, CEO of NeueHouse,<br />

"We are so passionate about bringing special people together, which is<br />

now more important than ever. As a members club and community for<br />

creators, innovators and thought-leaders, we've envisioned the ideal<br />

work and social space to recharge, celebrate, and connect."<br />

The perfect toast to the career of a designer who is making great<br />

strides in moving the culture forward. AC<br />

Designer Mark Grattan<br />

58 aphrochic issue eight 59

Culture<br />

Interior designer Chloe Pollack-Robbins<br />

and artist Fernanco Mastrangelo<br />

Tiana Webb Evans of ESP Group and<br />

curator Danny Dunson<br />

Guests gathered at The Gallery<br />

Bar to celebrate designer<br />

Mark Grattan<br />

60 aphrochic issue eight 61

Food<br />

Alkebulan<br />

Chef Alexander Smalls Curates as Taste of<br />

Africa’s Cultural Revolution for the World<br />

Food does so much more than just nourish our<br />

bodies. It brings us together. <strong>No</strong>t just as families,<br />

but as people. And because we’re all different,<br />

there are countless ways to prepare it, serve it and<br />

take it in. Each one is attached to a culture — to<br />

a particular way of being human. Like cultures,<br />

food overlaps, weaving a fantastic tapestry of<br />

influences that shows where we are, where we’ve<br />

come from and who we’ve met along the way. If<br />

you listen, food will tell you a story. Few people<br />

know that as well as Chef Alexander Smalls.<br />

Words by Bryan Mason<br />

Photos from Alkebulan<br />

62 aphrochic

Food<br />

The culinary mind behind<br />

some of New York’s most celebrated<br />

restaurants including<br />

its first Afro-Asian fusion<br />

spot, The Cecil, Chef Smalls<br />

is the author of several books<br />

exploring the history hidden in<br />

the food of the African Diaspora.<br />

This year he’s breaking new<br />

ground again as the curator of<br />

the first ever African Dining<br />

Hall fittingly titled, Alkebulan,<br />

being presented as part of Expo<br />

2020 Dubai. This 6-month-long<br />

world’s fair-style exhibition,<br />

which began in October and will<br />

run until March 2022, brings<br />

together the best the world has to<br />

offer in business, science, technology,<br />

art, and food with the<br />

concept of Connecting Minds,<br />

Creating the Future, and built<br />

around the mantra Opportunity,<br />

Mobility and Sustainability.<br />

Alkebulan is one of the<br />

ancient names of the African<br />

continent, perhaps the only<br />

surviving term to be indigenous<br />

to the land and its people. Alternately<br />

translated as “Mother of<br />

Mankind” or “Garden of Eden,”<br />

it’s unclear if other terms may<br />

have existed among the continent’s<br />

many languages. However,<br />

Alkebulan was widely used in the<br />

north and has been connected to<br />

the Ethiopians, Moors (Almoravids<br />

/ Almohades) Nubians and<br />

Carthaginians, among others. In<br />

its current iteration, Alkebulan<br />

is a dining hall the likes of which<br />

has never been seen, pulling<br />

from many of the continent’s<br />

major food traditions as seen<br />

through the eyes of those who<br />

are leading its culinary renaissance.<br />

“It’s really about raising<br />

the profile, and bringing into<br />

the light of day, the gifts of<br />

African food,” Smalls says of the<br />

endeavor. “I brought in some<br />

of the top chefs who are really<br />

making a name for themselves,<br />

but also leading the conversation<br />

around the evolution / revolution<br />

of the new Africa table.”<br />

The result is 22,000 square<br />

feet of unimaginable culinary<br />

delights. Among the leaders<br />

of this exciting new school are<br />

Joburg-based Congolese chef,<br />

Coco Reinartz, Senegalese<br />

pastry chef Mame Sow, Kenyan<br />

celebrity chef, Kiran Jethwa and<br />

French-Congolese, Afro-Vegan<br />

chef Glory Kabe. The complete<br />

hall boasts 10 original concepts,<br />

3 of which were created by Chef<br />

Smalls himself. The fortuitous<br />

outcome of some skillful pivoting<br />

after a collection of misfortunes<br />

brought on by the COVID-19<br />

pandemic, the Alkebulan dining<br />

hall is that rarest of happenings:<br />

the right thing in the right place<br />

at the right time — an unprecedented<br />

opportunity to showcase<br />

Africa’s culinary culture on a<br />

world stage. For Chef Smalls, it’s<br />

the next step in a journey that he<br />

started a long time ago.<br />

“After my first restaurant<br />

I understood that, more<br />

than a chef / restaurateur, I<br />

was an activist,” he reflects.<br />

“The point was elevating and<br />

expanding the narrative of<br />

the art and food of the African<br />

Diaspora.” In bringing together<br />

so many parts of the continent<br />

and the new visions that are<br />

putting them back in conversation<br />

with food culture in the<br />

rest of the world, Chef Smalls is<br />

continuing the story he began<br />

with his book, Between Harlem<br />

and Heaven — that not only did<br />

Africa never leave these conversations,<br />

it’s been there from<br />

the start. “Through slavery,”<br />

he says. “Africa is the foundation<br />

of cooking and hospitality<br />

on five continents. Since then,<br />

institutional racism has really<br />

oppressed us, our products and<br />

our value.” The stories told in the<br />

concept and menus of Alkebulan<br />

are an important step towards<br />

correcting that narrative.<br />

Food isn’t the only way to<br />

tell our story, so the experience of<br />

Alkebulan doesn’t stop at the table.<br />

Accompanying it’s food offerings<br />

are the art of Nigerian textile<br />

designer Nike Davies-Okundaye,<br />

Ghanaian sculptor and<br />

66 aphrochic issue eight 67

Food<br />

Chef Alexander Smalls<br />

68 aphrochic

weaving artists, Theresah Ankkomah and<br />

Rufai Zakaris, a Ghanaian artist whose figurative<br />

works are made from single-use plastics<br />

found on the street. Completing the ambience<br />

is music from a variety of artists and DJs,<br />

including R&B singer, Khandice, DJ Patchoulee,<br />

and steel pannist Justin Homer.<br />

For world travelers, fans of Diaspora<br />

culture, and everyone who loves to eat,<br />

Alkebulan is an amazing opportunity to get a<br />

taste of the continent, past, present and a very<br />

bright future. As events like this become more<br />

common, more parts of the Diaspora will have<br />

a chance to share their part of the story and<br />

new perspectives on where Africa fits in our<br />

global food story will be formed, creating the<br />

possibility for something even greater. For<br />

Alexander Smalls, it’s likely that he sees it all<br />

already and he’s just waiting for us to catch<br />

up. In the meantime, he’s just taking it all as<br />

it comes, one step at a time. “It's just gifts,” he<br />

muses. “The universe worked it out for me to<br />

be able to do something like this with people<br />

who I have such respect for. It’s truly tremendous.”<br />

AC<br />

issue eight 71

Food<br />

72 aphrochic

Travel<br />

A Place To Gather<br />

More Than a Hotel, Philadelphia’s The Deacon<br />

Is a Space for Community<br />

Philadelphia is a city of neighborhoods. Each block is distinct,<br />

with its own special vibe. It’s the birthplace of our democracy and<br />

is home to some of the nation’s oldest architecture. On any given<br />

street, you can run into a historical site, and that’s exactly what<br />

happened when developer Everett Abitbol found an about-to-be<br />

demolished building that he would transform into one of the city’s<br />

most exciting new boutique hotels.<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays<br />

Images by Jillian Guyette<br />

issue eight 75

Travel

Travel<br />

The former First African Baptist Church, originally built in<br />

1906, had a wall that was falling into the street when Abitbol discovered<br />

it. The church had been a place of refuge for South Philadelphia’s<br />

prominent Black community in the early 1900s. The same community<br />

that W.E.B. DuBois studied and wrote about in The Philadelphia Negro.<br />

After the church closed its doors, moving the congregation into a<br />

bigger space, the historic building had fallen into disrepair. Knowing of<br />

the rich community history of the First African Baptist Church, Abitbol<br />

decided he wanted to restore the building as a “community asset.”<br />

He turned to Philadelphia native Shannon Maldonado, hiring her<br />

as the creative director for what would become a hotel and community<br />

space in the Graduate Hospital neighborhood of the city. Maldonado,<br />

the owner of popular Philly boutique, YOWIE, is known for her love of<br />

color, eye for artisanship, and her signature minimalist aesthetic. And<br />

The Deacon offers all of that and more, with a Bauhaus design aesthetic.<br />

In beautifully appointed rooms, guests can interact with history,<br />

as the original stain glass from the church remains part of the architecture.<br />

Or they can gather in the common areas where Maldonado<br />

used color to create an enveloping and cozy experience.<br />

Beyond the rooms, the hotel was designed to honor its roots, and<br />

remain a place for the community to gather. On any given day, guests<br />

and neighborhood residents can find an interesting event to attend.<br />

From self-care slumber parties led by Freedom Apothecary to an<br />

evening of Latin dance, where guests are led through lessons of basic<br />

steps of Salsa by AfroTaino, every month there’s a host of unique gatherings<br />

to take part in.<br />

A place to gather, relax, and enjoy, The Deacon is a unique space<br />

designed for one-of-a-kind experiences and is now the new heart of<br />

Philadelphia’s Graduate Hospital neighborhood. AC<br />

You can book your stay and/or experience at thedeaconphl.com.<br />

78 aphrochic

Travel<br />

80 aphrochic issue eight 81

Wellness<br />

Back to Life<br />

Returning to the World After Long-Haul COVID<br />

It’s been more than a year since COVID-19 came and changed the world. After<br />

19 months of suffering, death and fear, rising vaccination rates and a declining<br />

number of daily cases has many of us ready to take our first steps back into<br />

real life — not life as it was before, but better, safer and with a new understanding<br />

of what’s really important.<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays<br />

Photos by Bryan Mason and Jeanine Hays<br />

82 aphrochic

Wellness<br />

Jeanine and Bryan head into the<br />

mountains for a hike with their Nike<br />

Therma-FIT Golf Jackets<br />

84 aphrochic

Wellness<br />

The First Months of the Pandemic<br />

Our COVID journey started in February 2020. Bryan wasn’t<br />

feeling well. He had a deep pain in his back and could barely move.<br />

The day before he’d been fine and then suddenly we were close to<br />

going to the emergency room. Instead we opted to wait and see our<br />

doctor the next day. In the morning, it was hard for him to walk and I<br />

had to help him put his shoes on. In more than 20 years together, I had<br />

never seen him so ill.<br />

When we got to the doctor’s office. I had to help him into the<br />

building. The doctor sent us for a chest x-ray. It was a sunny day and<br />

the x-ray facility was just a few blocks away, so we walked.<br />

The test didn’t take long. Instead of the results, we got an urgent<br />

call from the doctor. Bryan had a severe double pneumonia. The<br />

technicians were surprised he was even standing. One lung was so<br />

full of fluid that it was pushing the other lung to the side.<br />

The next two months were a blur. COVID quickly went from<br />

being a rumor to a reality to a nightmare. Lockdowns were happening<br />

all over the country, but we were already inside. Bryan was confined<br />

to the couch while I cooked and tended to him and worked to keep our<br />

business running. Over that period of caring for him, there were a few<br />

days where I felt sick. Just some stomach cramps, nothing serious. I<br />

thought it must have been a stomach bug. It was gone in a few days<br />

and I never really thought about it.<br />

We made our way to Mount Sinai for a COVID test on the same<br />

day that New York City announced the lockdown. It came back<br />

negative (they were only 70% effective then), so they treated his<br />

pneumonia. The pain eventually subsided but his recovery was slow.<br />

It took two months for him to stop sleeping on the couch and longer<br />

for him to sleep through the night. Our doctor wasn’t convinced<br />

that his illness wasn’t COVID so she researched along with us to get<br />

caught up on the quickly moving science around the virus.<br />

By May he was better, and for a few weeks things were good.<br />

Then one day it felt like my skin was on fire. I broke out in hives all<br />

over my body. The doctor suggested hydrocortisone cream and<br />

lotion. It worked. A couple of weeks later, my feet were covered in<br />

a red rash. Then sometimes when I’d eat, my throat would begin to<br />

swell. It was strange, but none of it sounded like COVID.<br />

In June our doctor suggested that we get an antibodies test. By<br />

then the technicians could come directly to your home to draw blood.<br />

A couple of weeks later we learned that we both had COVID-19 antibodies.<br />

We had both had COVID.<br />

It was upsetting to hear that. People were dying in New York<br />

City from this awful virus. The former governor was giving us daily<br />

updates. The JAVITS Center was a triage center. But Bryan was better<br />

and my current symptoms didn’t match anything that was being said<br />

about COVID. We didn’t start hearing about the long-haulers until<br />

later.<br />

The Summer of 2020<br />

June and July were ok. Like everyone else in New York, we<br />

spent our days looking out the window of our apartment like fish in<br />

a bowl. We offered the magazine free online and started a series of<br />

live podcasts. We had just finished lunch after a live podcast in August<br />

when my throat began to swell. But this time it felt like I was choking,<br />

dying. I couldn’t breathe. I almost blacked out. I screamed for Bryan<br />

to give me an EpiPen shot. We had never used one before — never<br />

needed one, but the doctor had suggested getting one since I was<br />

having these weird allergy attacks. Thankfully it had just arrived that<br />

week. My throat opened back up and we headed to the ER.<br />

I was observed by the hospital staff for about an hour and then<br />

sent home with another EpiPen and some prednisone. The next day<br />

it happened again. I needed another shot of epinephrine to breathe. I<br />

was terrified. What was happening?<br />

For two weeks I deteriorated. I couldn’t eat things I normally ate<br />

any longer. Bryan researched anti-inflammatory foods and created<br />

a vegan diet for me with vegetables that helped deal with inflammation<br />

in the body. I had to wear a mask all day inside our apartment<br />

because everything was making me sick. I could no longer sleep in<br />

our bedroom. We bought an air purifier because there was something<br />

in the air causing me to feel worse.<br />

We’d decided over the summer that we were going to leave the<br />

city and were waiting to close on a house. But we needed to leave the<br />

apartment sooner. Bryan packed up all he could and we left Brooklyn<br />

in early September to stay at a friend’s place in Manhattan while she<br />

was upstate. I never saw our apartment again.<br />

It was hard for me to walk. I needed constant air conditioning<br />

because humidity would cause my throat to swell. My diet was<br />

extremely limited — only about 7 different fruits and vegetables - and<br />

I was on 10 medications just to breathe. We looked for help. I tried to<br />

get into COVID care clinics at Johns Hopkins and the Mayo Clinic but<br />

was rejected. When our doctor heard that the Mount Sinai Center for<br />

Post-COVID Care had opened we called, but they had a six-month<br />

waiting list. I couldn’t go until March 2021. So Bryan started building<br />

our own care team.<br />

I saw a rheumatologist and a series of allergists. <strong>No</strong>ne were very<br />

familiar with COVID, but we were able to rule out rheumatological<br />

issues. One of my allergists was completely uninterested in hearing<br />

about my experience. Whether it was because I’m Black, a woman, or<br />

both, I don’t know, but she remained convinced that I had a long-term<br />

undiagnosed case of herpes. So we found a different allergist.<br />

What was supposed to be a few weeks of staying in our friend’s<br />

apartment turned into months moving around Manhattan as our<br />

closing date got pushed back again and again due to various issues<br />

with the pandemic and the process itself. Finally, in mid-<strong>No</strong>vember<br />

we closed and moved into our new home. For a couple of weeks life<br />

86 aphrochic

Wellness<br />

Jeanine and Bryan lace up for a run in the park. Bryan is wearing Nike Air Force 1 Luxe shoes and Jeanine is wearing Nike React<br />

Infinity Run shoes.<br />

felt absolutely perfect — then it all got much, much worse.<br />

It started when a plant we received as a housewarming gift triggered<br />

an extreme reaction. I broke out in hives, my throat began to close, I needed<br />

two EpiPens and an ambulance. The EMTs were so kind. One had heard of<br />

post-COVID syndrome and seemed quite interested in all that had been<br />

happening to me. They said they would remember us if well called again.<br />

They wanted to be sure to arrive quickly if I had another attack.<br />

More prednisone followed, my second large dose in less than a year.<br />

It weakened my immune system, and an infection quickly spread from<br />

my mouth to my throat to my entire body. I couldn’t talk. I didn’t want to<br />

eat. Everything hurt. I could only communicate through grunts and tears,<br />

which made things hard for Bryan. I laid in bed day after day getting worse<br />

and worse, weaker and weaker. We saw an ear nose and throat specialist<br />

and then an infectious disease specialist. I needed to be weaned off the<br />

prednisone, but it had to be extremely slow because my body would react<br />

badly to fast tapering.<br />

Care For The Long Haul<br />

For two months I went through something called decompensation.<br />

I wasn’t eating so I lost too much weight. I couldn’t walk or talk and slept<br />

most of the day. It felt like dying. All I was holding on to was that I didn’t want<br />

my husband to be left all alone. I tried to gather strength for him. I wanted<br />

to live.<br />

He took care of me. Blending my food into smoothies, making<br />

homemade apple sauce. Anything that I could keep down. I refused most<br />

of it, but he knew that if I could make it to March, to the post-COVID center,<br />

Jeanine gets into her morning exercise<br />

routine, wearing a Nike Swoosh Luxe Bra<br />

and Nike Sportswear Tech Pack Pants.<br />

88 aphrochic issue eight 89

Wellness<br />

that I could get better. He never stopped<br />

believing. And he was right.<br />

In March 2021, we borrowed a<br />

neighbor’s car (we bought one but it was<br />

stuck in Texas, buried under snow) and<br />

drove down to the city. My clothes were<br />

hanging off my body. I talked slowly. I had<br />

brain fog caused by COVID, and Bryan<br />

needed to speak for me most times,<br />

reading through a diary of symptoms<br />

that we had been keeping since the last<br />

spring. I was re-learning how to talk,<br />

walk, even go to the bathroom again. The<br />

doctor was attentive. She listened. Then<br />

she said something I’ll never forget —<br />

“Everyone who comes here gets better.”<br />

Those were the words what I<br />

needed to hear. I knew that God had<br />

brought us to the right place. They<br />

said that what I was going through<br />

wasn’t new. They’d seen hundreds of<br />

similar cases. While the Post-COVID<br />

Care Center had been started for the<br />

most critical COVID-19 cases, those<br />

who had been hospitalized and needed<br />

oxygen, they found that thousands of<br />

New Yorkers were dealing with “longhaul<br />

COVID.” Long-haulers usually<br />

started with very mild symptoms, like<br />

my stomach bug, but COVID triggered<br />

something in the body, and months later<br />

they developed a variety of symptoms.<br />

They told Bryan that he had done<br />

an incredible job taking care of me and<br />

building my care team, and that now I<br />

needed physical therapy, a pulmonary<br />

specialist, and a neurologist. Within<br />

weeks I had new diagnoses of a blood<br />

pressure issue called POTS that was<br />

common in post-COVID patients, and<br />

peripheral neuropathy which caused<br />

extreme nerve pain, making it hard to<br />

walk. Where there was once no light at<br />

the end of the tunnel, they told me that I<br />

would be much better within six months.<br />

I really couldn’t imagine it. I had<br />

such a long way to go. But we worked<br />

hard. The physical therapy center had a<br />

special post-COVID regimen that had<br />

been developed by the Care Center.<br />

And I did my part. Where the schedule<br />

suggested physical therapy 2-3 times a<br />

week, I wanted to work out daily. I also<br />

had to start eating full meals again. It was<br />

work. Hard work. But in a few months,<br />

my appetite was back, and I could even<br />

eat meat again. My body was sorely in<br />

need of protein.<br />

Bryan was my nutritionist, physical<br />

therapist and mental wellness counselor.<br />

There were so many days I wanted to give<br />

up. Days I just felt bad for myself, days<br />

I was just mad at the world — why did<br />

COVID even exist? But every day he encouraged<br />

me to work hard, getting my<br />

mind and body fit, and now, six months<br />

later, I’m sitting here writing this article,<br />

able to walk again, and enjoy life again.<br />

Return to Life<br />

My COVID journey isn’t over. The<br />

virus has left me with chronic idiopathic<br />

urticaria — a condition where your<br />

body can randomly have severe allergic<br />

reactions, from hives to anaphylaxis —<br />

POTS, peripheral neuropathy, alopecia<br />

and textile dermatitis. We have to be<br />

so careful that sometimes I feel like a<br />

woman in a bubble. I take an air purifier<br />

with me when visiting family to make<br />

sure that the air around me is clean. And<br />

I don’t go to restaurants, because I need<br />

to avoid ingesting anything that might<br />

cause my skin to break out or my throat<br />

to close. So my husband has turned our<br />

kitchen into the best restaurant in New<br />

York, and he makes all of my meals to be<br />

sure they’re safe. We don’t have plants<br />

anymore. Just faux branches around<br />

the house. The doctors don’t know if I’ll<br />

always have these issues or if one day<br />

they’ll just disappear. There’s still a lot<br />

more to figure about post-COVID and<br />

how it impacts the body long term.<br />

But that’s not what’s important.<br />

What matters is that, for the first time in<br />

more than a year, my husband and I are<br />

both healthy again. Every morning we<br />

wake up and exercise. My body moves<br />

again, my mind is clear again, I spend<br />

every day eating amazing food and going<br />

up and down the stairs like I used to —<br />

even better actually, since I lost about<br />

100 pounds in the last year. I always<br />

used to walk a lot, but now I love to walk<br />

because I know what it’s like to not be<br />

able to. I love to drive with Bryan to the<br />

lookout on the mountains near our<br />

home and look out over as much of the<br />

world as I can see.<br />

Finally, it feels like we’ve reached<br />

a turning point. Fully vaccinated, ready<br />

to get our boosters, we are starting to<br />

enjoy life again. In our new home, we’re<br />

designing a wellness room. We’re in there<br />

every morning doing my physical therapy.<br />

Soon it will be a room that supports meditation<br />

and yoga practice as well. With<br />

gear from Nike to help us with our daily<br />

workouts, we’re building our physical<br />

and mental wellbeing as we continue to<br />

recover from this virus and its impact on<br />

our lives. It took a lot of steps to get here,<br />

and there might still be some stumbles<br />

ahead, but I’m looking forward to every<br />

step we take from here. AC<br />

See the MOOD section for the capsule<br />

collection Jeanine and Bryan curated with<br />

Nike to get back to life.<br />

90 aphrochic issue eight 91

Wellness<br />

COVID Resources<br />

Centers for Disease Control: cdc.gov<br />

World Health Organization: covid19.who.int<br />

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health: publichealth.jhu.edu<br />

Mount Sinai Center for Post-COVID Care: mountsinai.org/about/covid19/center-post-covid-care<br />

I N T E R I O R S<br />

N E W Y O R K<br />

A P H R O C H I C . C O M<br />

92 aphrochic issue eight 93

Reference<br />

The Structure<br />

of Diaspora<br />

This series on the African Diaspora began by listing some<br />

of the many questions that surround the African Diaspora,<br />

and diasporas as a whole. Without doubt the most persistent<br />

of these is simply, “What is it?” Ultimately, it’s a question<br />

of structure: “What is it that makes a diaspora?” But like<br />

many simple questions, this one is made up of a seemingly<br />

endless stream of other questions, making the process of<br />

answering it incredibly complex.<br />

Words by Bryan Mason<br />

94 aphrochic issue eight 95

Reference<br />

Search the term online and you’ll find a lot<br />

of answers and any number of definitions, most<br />

of which will likely differ only in the smallest<br />

details. But studying diasporas is a game of<br />

inches and those small differences in definition<br />

can mean big differences in how the concept is<br />

actually applied and which groups it is applied<br />

to. And so, this simple question has plagued<br />

the study of diasporas for years. For the African<br />

Diaspora, it may have been a question from the<br />

beginning, but that depends on when you think<br />

the beginning actually was.<br />

When do we start? And how?<br />

Since his 1966 introduction of the term,<br />

Joseph E. Harris was instrumental in shaping<br />

the discourse of modern African Diaspora<br />

theory. His Introduction to the African Diaspora<br />

marked a seismic shift in the way in which Africa-descended<br />

peoples from around the globe<br />

considered and addressed their collective circumstances.<br />

In another introduction — one<br />

that was appended to the 1993 second edition<br />

of Global Dimensions of Diaspora — Harris gives<br />

a brief definition of his concept of diaspora.<br />

According to Harris, “the African Diaspora<br />

concept subsumes the following: the global dispersion<br />

(voluntary and involuntary) of Africans<br />

throughout history; the emergence of a cultural<br />

identity abroad based on origin and social<br />

condition; and the psychological or physical<br />

return to the homeland, Africa.”<br />

By conceiving of the African Diaspora in<br />

this way, beginning with the voluntary — as<br />

well as involuntary — movements of Africans<br />

in antiquity, Harris expands the concept in<br />

time and space, looking beyond the temporal<br />

boundaries of the trans-Atlantic slave trade<br />

and the geographic borders of the Black Atlantic<br />

to the long periods of African movement that<br />

pre-date both. Prior to the dispersion of the<br />

16th-19th centuries, Africans moved about the<br />

world in a variety of capacities, both free and<br />

enslaved. Their presence and efforts bolstered<br />

the spread of both Christianity and Islam as<br />

world religions, and aided the development of<br />

the ancient and medieval worlds in many places<br />

including Greece, Rome and Spain. The effect<br />

of this expansion, for Harris, is to preserve the<br />

African Diaspora from being confined exclusively<br />

to a legacy of new world slavery. This<br />

larger historical purview enables Diaspora to be<br />

read as a story of African achievement abroad<br />

in addition to the more usual tales of subjugation<br />

and woe. It also brings up some important<br />

points to consider.<br />

The first point to consider in Harris’ construction<br />

of Diaspora, at this point in the conversation,<br />

is how it changes the relationship<br />

between the Diaspora and Pan-Africanism. In<br />

situating the origins of the African Diaspora<br />

in the voluntary movements of Africans in<br />

antiquity, Harris removes the trans-Atlantic<br />

Slave trade as the direct catalyst for the Diaspora<br />

and by extension, Pan-Africanism as the direct<br />

predecessor of the African Diaspora. Conversely,<br />

British historian, George Shepperson, who<br />

also introduced the African Diaspora concept<br />

in 1966, describes the Diaspora as,“a series of<br />

reactions to the imposition of the economic and<br />

political rule of alien peoples in Africa, to slavery<br />

and imperialism.” As scholar Carlton Wilson<br />

would reflect, though Shepperson too called for<br />

an expansion of the diaspora concept, he nevertheless,<br />

“saw the slave trade, slavery, the period<br />

of imperialism, and the partition of Africa as<br />

being the focus of the African Diaspora.”<br />

The difference between Harris’ and Shepperson’s<br />

constructions of the African Diaspora<br />

brings about an interesting paradox. On the<br />

one hand, it is both desirable and necessary to<br />

tell a story of Diaspora that is not confined to<br />

the ramifications of the trans-Atlantic slave<br />

trade. However, a function-based approach to<br />

the African Diaspora will necessarily fall closer<br />

to Shepperson’s view, as it was not the needs<br />

of Africans in antiquity but in the modern age<br />

of slavery, colonization, and imperialism that<br />

led to the emergence of the African Diaspora<br />

concept. And it is the needs of the world in<br />

the aftermath of these events that the African<br />

Diaspora concept must serve.<br />

Forced Movement or Just Movement?<br />

At stake within this small distinction is the<br />

question of how diasporas begin and specifically<br />

the looming issue of forced migration - whether<br />

the condition of diaspora can only exist when<br />

migrants are forced into movement by war, exile<br />

or in the case of the African Diaspora, centuries<br />

of capture and trade across deserts and seas.<br />

While traditionally, the first dispersed communities<br />

discussed as diaspora, beginning with<br />

the Jewish, all had forced movement as their<br />

starting point, increasingly in recent years the<br />

cause of the movement has been considered<br />

far less important if not completely immaterial.<br />

This is particularly true in the study of internal<br />

diasporas, comprised of people born in a particular<br />

country who have simply moved to another<br />

part of the same country.<br />

The online resource WorldAtlas lists the<br />

4 million Americans who moved from their<br />

home states to other American states in 2010<br />

and the millions more who have moved from the<br />

interior of China to the nation’s coastal cities as<br />

examples of internal diasporas. So not only are<br />

we lacking consensus on whether it’s important<br />

to consider why communities were dispersed<br />

before terming them diasporas, it’s not even<br />

clear how far they have to go before the term can<br />

be applied. Because of the lack of clarity on basic<br />

points, attempting to understand the makeup of<br />

the African Diaspora — and diasporas as a whole<br />

— can easily become a process of going in rhetorical<br />

circles. Case in point: this question of<br />

forced migrations brings us back to a question<br />

that this series has already posed. If forced<br />

dispersion is not a necessary prerequisite to<br />

diaspora, then any movement by a group of<br />

people from one place to others — regardless of<br />

distance — will logically result in a diaspora. And<br />

if that’s the case, then why study diasporas at all?<br />

Worst Things First<br />

For as long as there have been people,<br />

there has been movement. Diaspora exists as<br />

a separate category to migration specifically<br />

because forced movement is the anomaly.<br />

Without it, none of the other factors thought<br />

to be defining aspects of diasporas fit. Harris’<br />

ideas on common cultural identity, common<br />

economic condition and the dream of return<br />

— all standard components in most definitions<br />

of diaspora — are far less certain realities for a<br />

group of people who voluntarily left a particular<br />

place than for people exiled or forcibly removed.<br />

Africans who left the continent to travel the<br />

world in antiquity did so in a number of different<br />

socio-economic states and with a wide variety of<br />