AphroChic Magazine: Issue No. 15

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

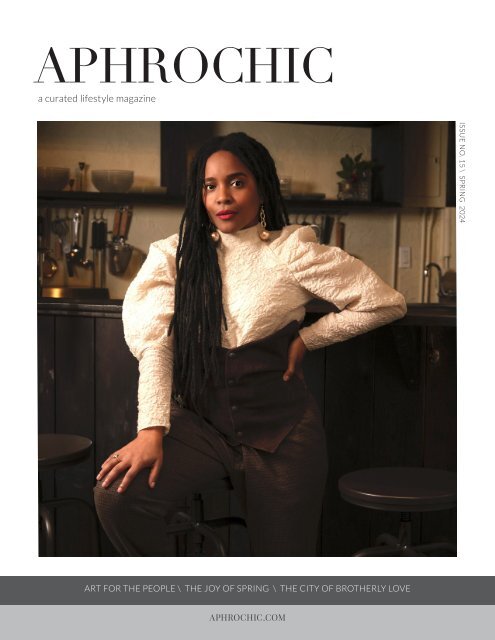

APHROCHIC<br />

a curated lifestyle magazine<br />

ISSUE NO. <strong>15</strong> \ SPRING 2024<br />

ART FOR THE PEOPLE \ THE JOY OF SPRING \ THE CITY OF BROTHERLY LOVE<br />

APHROCHIC.COM

In <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>No</strong>. <strong>15</strong> of <strong>AphroChic</strong> we explore the worlds of creatives who are showing us the<br />

sheer depth and breadth of Black culture in the 21st century. Black culture is everywhere<br />

— in food, fashion, down historic city streets, and in some of the world’s greatest cultural<br />

institutions. In this spring 2024 issue, where we’re almost a quarter into the century,<br />

we’re shining a light on the ways in which Black culture is discovering new ways to honor<br />

our past, build a better and more equitable present, and radically reimagine our future.<br />

Chef Rasheeda Purdie graces the cover. She is the woman behind Ramen by Ra, New York City’s first Black- and woman-owned<br />

ramen restaurant. We feature the work she is doing, breaking new ground in the culinary world by bringing together<br />

traditional Japanese ramen and southern soul food to create dishes that wow the palette and honor her cultural heritage.<br />

In Brooklyn, we take you inside the exhibit that has art-lovers’ hearts afire, Giants: Art From The Dean Collection of Swizz Beats<br />

and Alicia Keys at the Brooklyn Museum. We explore how the couple has redefined the role of art collectors, elevated the value of<br />

contemporary Black art, and brought art to the people. Then we head to Detroit where another musician, BLKBOK, is blending<br />

classical with Hip Hop, telling stories of Black history through a sound that is all his own.<br />

In City Stories we travel to Philadelphia, exploring the historic stone streets, architectural marvels, murals and cultural<br />

centers that are part of the rich Black history of the nation’s first capital. And in Artists & Artisans, we share with you the work of<br />

photographer Carla Williams, whose debut monograph, Tender, explores a young, queer, Black woman’s identity through the lens<br />

of her camera.<br />

In a world that feels like it’s growing more chaotic by the day, we offer a new series for 2024 — Radically Reimagined. This<br />

series is an exploration of how we all can be part of designing a better world through radically reimagining, deconstructing,<br />

and developing new paradigms. And in Civics we take a solution-oriented approach to addressing the many genocides that are<br />

happening globally, providing you with resources on how to help bring an end to the practice of deliberately killing and eradicating<br />

nations and ethnic groups around the world.<br />

For uplifting inspiration, we share with you master floral designer John L. Goodman’s spring tablescape, inspired by one of<br />

his favorite books — The Complete Adventures of Peter Rabbit. In Fashion, we take you inside the world of Kwasi Paul, the mens and<br />

womenswear fashion label by designer Samuel Boakye that blends his New York and Ghanaian roots through bold silhouettes and<br />

lots of color. And in Interior Design, we visit the upstate New York home of Brazilian designer Ana Claudia Schultz.<br />

As with every issue of <strong>AphroChic</strong>, we’re here to show you the beauty and diversity of the African Diaspora, from Black thought<br />

to art, fashion, and design. The world may be chaotic 24 years into the 21st century, but across the Diaspora the future is indeed<br />

very bright.<br />

Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Founders, <strong>AphroChic</strong><br />

Instagram: @aphrochic<br />

editors’ letter

SPRING 2024<br />

DEPARTMENTS<br />

Read This 10<br />

Visual Cues 12<br />

Coming Up 14<br />

The Black Family Home 16<br />

Mood 26<br />

FEATURES<br />

Fashion // A World Within Itself 30<br />

Interior Design // A Mid-Century Modern Dream 40<br />

Culture // Art for the People 56<br />

Food // Soul Ramen 68<br />

Entertaining // The Joy of Spring 74<br />

City Stories // The City of Brotherly Love 80<br />

Reference // Radically Reimagined 96<br />

Wellness // Resetting Your Way to a Better Life 104<br />

Sounds // BLKBOK: Where Hip Hop Meets Classical 106<br />

PINPOINT<br />

Artists & Artisans 114<br />

Civics 120<br />

Who Are You? 126

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

Cover Photo: Rasheeda Purdie<br />

Photographer: Rashida Zagon<br />

Publishers/Editors: Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Creative Director: Cheminne Taylor-Smith<br />

Editorial/Product Contact:<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong><br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong>.com<br />

magazine@aphrochic.com<br />

Brand Partnerships and Ad Sales:<br />

Krystle DeSantos<br />

Krystle@aphrochic.com<br />

Contributors:<br />

Ruby Brown<br />

Chinasa Cooper<br />

issue fifteen 9

READ THIS<br />

As James Baldwin said, “If you know whence you came, there is really no limit to where you can go.” History is a<br />

great teacher, and to know one's history is also a great way to chart one's future. In this issue's list of important<br />

books, <strong>AphroChic</strong> looks to important Civil Rights figures and events. Medgar and Myrlie Evers fought to desegregate<br />

the University of Mississippi, organized picket lines and boycotts, and survived a firebombing of their home. When<br />

Medgar was assassinated by the Klan in 1963, Myrlie continued their work in his name. Their love story was at the<br />

heart of everything they did, and it's intertwined with their passion for the Civil Rights Movement in Medgar &<br />

Myrlie. Constance Baker Motley, who finally gets her due in Civil Rights Queen, was the first Black woman to argue a<br />

case in front of the Supreme Court, she defended Martin Luther King Jr. in Birmingham, helped to argue in Brown<br />

vs. The Board of Education, and played a critical role in fighting Jim Crow laws throughout the South. And Tragedy on<br />

Trial puts the spotlight on the shocking story of the 1955 trial of Emmett Till's murderers, particularly the fearless<br />

efforts of Mamie Till and the courageous friends and family who testified.<br />

Civil Rights Queen<br />

by Tomiko Brown-Nagin<br />

Publisher: Vintage. $18.99<br />

Tragedy on Trial<br />

by Ronald K.L. Collins<br />

Publisher: Carolina Academic<br />

Press. $25.99<br />

Medgar & Myrlie<br />

by Joy-Ann Reid<br />

Publisher: Mariner Books. $29<br />

10 aphrochic

Celebrate Black homeownership and the<br />

amazing diversity of the Black experience<br />

with <strong>AphroChic</strong>’s newest book<br />

In this powerful, visually stunning book, Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason explore<br />

the Black family home and its role as haven, heirloom, and cornerstone of Black<br />

culture and life. Through striking interiors, stories of family and community,<br />

and histories of the obstacles Black homeowners have faced for generations,<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong> honors the journey, recognizes the struggle, and embraces the joy.<br />

AVAILABLE WHEREVER BOOKS ARE SOLD

VISUAL CUES<br />

William Henry Johnson (American, 1901–1970). Woman in Blue, c. 1943. Oil on<br />

burlap. Framed: 35 × 27 in. (88.9 × 68.6 cm). Clark Atlanta University Art Museum,<br />

Permanent Loan from the National Collection of Fine Art. Courtesy Clark Atlanta<br />

University Art Museum.<br />

The Metropolitan Museum of Art is presenting a new<br />

exhibit, The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic<br />

Modernism, as the first African American–led movement<br />

of international modern art. With 160 works of<br />

art on display through July 28, it showcases how Black<br />

artists portrayed everyday modern life in the new<br />

Black cities of the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s. In those<br />

decades of the Great Migration, millions of African<br />

Americans moved north from the segregated rural<br />

South. At the core of the exhibition are artists who<br />

shared a commitment to depicting the Black subject in<br />

a radically modern way, refusing the racist stereotypes<br />

of the day. Paintings, sculpture, film, and photography<br />

are featured from artists such as Charles Alston,<br />

Aaron Douglas, Meta Warrick Fuller, Palmer Hayden,<br />

Bert Hurley, William H. Johnson, Archibald Motley, Jr.,<br />

Winold Reiss, Augusta Savage, James Van Der Zee, and<br />

Laura Wheeler Waring. A powerful gallery features<br />

Romare Bearden’s <strong>15</strong>-foot-wide series of collages, The<br />

Block (1970), from The Met collection, offering a town<br />

house row in mid-century Harlem and that sustains<br />

the legacy of the Harlem Renaissance. Many of the<br />

pieces in the exhibition come from the collections of<br />

Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs),<br />

including Clark Atlanta University Art Museum,<br />

Fisk University Galleries, Hampton University Art<br />

Museum, and Howard University Gallery of Art. For<br />

more information, go to metmuseum.org.<br />

12 aphrochic

DIVINE<br />

FEMININITY<br />

BY FARES MICUE<br />

P E R I G O L D . C O M

COMING UP<br />

Events, exhibits, and happenings that celebrate and explore the African Diaspora.<br />

The Black Cowboy Festival<br />

May 23-26 | Rembert, SC<br />

The Black Cowboy Festival is an annual event that<br />

celebrates the historical and contemporary significance<br />

of African American contributions to cowboy<br />

and frontier culture. It's estimated that one in four<br />

of the Old West cowboys were Black, many of whom<br />

were recently freed enslaved people migrating from<br />

the South. Black men and women on horseback were<br />

a symbol of power then, and the festival organizers<br />

celebrate that they still are today. In its 27th year, the<br />

festival includes competitive rodeo events, demonstrations,<br />

entertainers, horseback rides, line dancing,<br />

trail rides, calf roping, wagon rides, artifact displays,<br />

and food vendors.<br />

Learn more at blackcowboyfestival.net.<br />

American Black Film Festival<br />

June 12-16 | Miami<br />

The American Black Film Festival is an<br />

annual event dedicated to empowering<br />

Black talent and showcasing film and<br />

television content by and about people<br />

of African descent. The ABFF provides<br />

a platform for emerging Black artists —<br />

many of whom have become successful<br />

actors, producers, writers, directors and<br />

stand-up comedians. The event includes<br />

screenings, classes, seminars and cultural<br />

events.<br />

Learn more at abff.com/miami.<br />

Bronzeville Juneteenth Celebration<br />

June 17 | Chicago<br />

The historic Bronzeville neighborhood<br />

hosts an annual Juneteenth celebration<br />

that attracts thousands. Located on<br />

the south side of Chicago, Bronzeville<br />

became an established neighborhood<br />

around the turn of the 20th century as<br />

a result of the Great Migration. Today<br />

it's known as a cultural center and arts<br />

district. The Juneteenth event includes<br />

art installations, storytelling, visual and<br />

performing arts, historical tours, and<br />

more.<br />

Learn more at eventnoire.com.<br />

International Black Theatre Festival<br />

July 29-August 3 | Winston-Salem, NC<br />

<strong>No</strong>w in its 18th year, the International<br />

Black Theatre Festival attracts over<br />

65,000 attendees. The multi-day festival<br />

includes 100 theatrical performances, as<br />

well as films, spoken word poetry, youth<br />

programming, workshops, academic discussions,<br />

and an international vendor’s<br />

market showcasing art and crafts from<br />

the African Diaspora.<br />

Learn more at ncblackrep.org.<br />

14 aphrochic

BALTIMORE<br />

S P E A K S<br />

B L A C K<br />

C O M M U N I T I E S<br />

C O V I D - 1 9<br />

A N D T H E<br />

C O S T O F<br />

N O T D O I N G<br />

E N O U G H<br />

W R I T T E N A N D D I R E C T E D B Y<br />

B R Y A N M A S O N A N D J E A N I N E H A Y S<br />

V I S I T O U R W E B S I T E A T B A L T I M O R E S P E A K S . C O M

THE BLACK FAMILY HOME<br />

Representation Matters — Except When It Doesn’t<br />

There’s no denying the importance of representation<br />

as part of the current conversation on race in America,<br />

or American social discourse as a whole. With regard to the<br />

former, it has become such a prevalent aspect of the conversation,<br />

particularly in the aftermath of the Black Lives<br />

Matter (BLM) marches of 2020, that we’re almost expected<br />

to believe that the only reason Black people ever marched,<br />

protested, or boycotted was out of a burning desire to be<br />

“seen.” But how important is representation really, and<br />

what does it actually mean? In a world of performative<br />

allyship, Black business listicles, and plummeting interest<br />

in workplace Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI), we have<br />

to ask whether visibility, by itself, is a panacea or simply a<br />

placebo for real change?<br />

Representation and the Black Family Home<br />

One way to take a very brief measure of a relationship<br />

that certainly demands more extensive and in-depth examination<br />

is to compare measurable quantities in representation<br />

and community well-being over established periods of<br />

time. Anyone old enough to remember the '90s knows well<br />

that Black representation in pop culture staples like TV and<br />

movies comes in ebbs and flows. Anyone whose lifespan or<br />

historical knowledge reaches further back knows that the<br />

same is true for Black social and political advancements.<br />

Therefore, we can look at the level of Black representation<br />

on television and in film against some other measure<br />

of community prosperity to get some idea, even roughly,<br />

whether these ebbs and flows are happening at or around the<br />

same time.<br />

To fill in the other side of this comparison, there are<br />

any number of metrics to choose from. Median wealth,<br />

for example, is always a compelling and popular option.<br />

The Black Family Home is an<br />

ongoing series focusing on the<br />

history and future of what home<br />

means for Black families.<br />

This series inspired the new book<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong>: Celebrating the Legacy<br />

of the Black Family Home.<br />

Words by Bryan Mason<br />

Photos by Bruce Mars, Christina Morillo,<br />

Rajiv Perera and Jimmy Dean<br />

16 aphrochic

THE BLACK FAMILY HOME<br />

18 aphrochic

However, for the purposes of this consideration,<br />

there are a number of reasons to look<br />

instead at the Black family home.<br />

Even more than income, homeownership<br />

is a major component of wealth.<br />

As transferable assets, the generational<br />

sharing of homes is a large part of inheritances,<br />

which in turn have made up<br />

as much as 50% of wealth accumulation<br />

across the history of the United States. As a<br />

result, the perpetually lower rate of homeownership<br />

by Black Americans compared<br />

with white Americans is intrinsically<br />

linked to the overall and equally lasting<br />

disparity in wealth. Homeownership is<br />

also linked to health, whether through environmental<br />

justice issues such as lead<br />

exposure, water purity, and asthma risks,<br />

or through medical and economic disparities<br />

including food and medical deserts<br />

and redlining. There is a political aspect to<br />

housing and homeownership as well, with<br />

voting districts and gerrymandering determining<br />

much of who has say in legislative<br />

and policy decisions. In all, homeownership<br />

touches on many aspects of<br />

American life, such that gains in this area<br />

may — in very broad terms — suggest improvements<br />

in a number of areas where<br />

Black Americans are routinely kept lacking.<br />

By comparing levels of representation<br />

in television and film with levels of Black<br />

homeownership over specific periods of<br />

time, we can roughly discern the extent to<br />

which they mirror or follow one another.<br />

The point is not to establish a causal relationship,<br />

but to gauge in some small<br />

part whether there is a basis for assuming<br />

any relationship at all. Representation<br />

and social progress are not at all points<br />

congruent. And where they diverge, visibility<br />

in pop culture media can actually be<br />

used to disguise the backslides and backlashes<br />

that erode Black social and political<br />

gains.<br />

Black Representation in Film and Television<br />

1960 - 2000<br />

Black people have appeared in both<br />

issue fifteen 19

THE BLACK FAMILY HOME<br />

television and film since the earliest days of the two media. The<br />

19th century films, Horses. Gallop; thoroughbred bay mare (Annie<br />

G) with male rider, 1872-1875, by British innovator Eadweard<br />

Muybridge, and Something Good – Negro Kiss by director William<br />

Selig are two examples from the beginnings of film. Muybridge’s<br />

film features a Black rider atop a striding horse, while Selig’s 1898<br />

piece offered the first film depiction of African Americans kissing.<br />

Together these early films begin a legacy that would grow to<br />

include the nation’s first formally incorporated Black-owned film<br />

company — The Lincoln Film Company — and others through to<br />

the current day.<br />

Similarly, television has nearly always included a Black<br />

presence. Well ahead of the 1950s American TV boom, 1939's The<br />

Ethel Waters Show, an hour-long special starring the jazz vocalist<br />

and actress, was the first instance of a Black performer (of any<br />

gender) headlining their own show. Mixing comedy, music, and<br />

theater, the one-off event paired Waters with other notable<br />

Black performers such as Fredericka Washington and Georgette<br />

Harvey, as well as white performers like Philip Loeb.<br />

While the cited examples represent some of the high water<br />

marks of Black representation in the early days of TV and movies,<br />

the majority of depictions in both often fell into the racist tropes<br />

that were typical of the time, several of which persist in one form<br />

or another today. It was in the '50s and '60s that Black representation<br />

became both more widespread and took a turn from the<br />

initial depictions of servants, savages, and slaves.<br />

In film, change arrived with the coming of Sydney Poitier<br />

and Harry Belafonte. Both made careers of roles that depicted<br />

their characters, and Black people in general, with a type of<br />

dignity that had been lacking in earlier portrayals. Poitier’s first<br />

major role in 1950's <strong>No</strong> Way Out, is considered a pivotal moment<br />

in film culture as is Belafonte’s first major role in the 1954 film<br />

Carmen Jones. By the '70s the advent of so-called Blaxploitation<br />

films, led by Melvin Van Peebles 1971 classic Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss<br />

Song, not only opened new doors for empowered Black representation<br />

but rescued a film industry that was badly stagnating<br />

in the late '60s and nearing collapse. Films and directors of<br />

this era set the stage for the vanguard of the '90s which included<br />

directors like Spike Lee and John Singleton and a variety of acting<br />

talent that continues to grow today.<br />

The growth of Black representation on television began<br />

in the 1960s, as did representations of the Black family home.<br />

Sitcoms — which typically focus on life at home — were bringing<br />

Black people and our homes into view in new ways for the first<br />

time. Premiering in 1968, singer and actress Diahann Carroll’s<br />

Julia was the first weekly series to focus on a Black woman<br />

lead character that was not a servant to a white family. Julia<br />

was instead a nurse, widowed by the Vietnam war and raising<br />

her son. Julia was followed notably by Good Times, which was<br />

American television’s first depiction of a two-parent Black home<br />

and The Jeffersons, which lasted for more than 230 episodes and<br />

featured an affluent Black family. But undoubtedly one of the most<br />

impactful shows for depicting African American life in non-stereotypical<br />

roles was 1984’s The Cosby Show.<br />

Despite the deeply tarnished legacy of the show’s titular<br />

star, the program itself remains a landmark of representation for<br />

Black Americans, not only showcasing an affluent, professional,<br />

two-parent home, but storylines that involved these characters<br />

with art, theater and other forms of culture while addressing<br />

salient issues from an identifiably Black perspective. The<br />

success of the show set the stage for not only its own spin-off,<br />

1987’s A Different World, but 1990’s The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air and<br />

1993’s Living Single among several others. Between 1950 and 1999,<br />

Black representation on film and television reached new heights<br />

of depth and variety at a time when gains in education, income,<br />

and homeownership seemed to be advancing with similar pace.<br />

Black Homeownership 1960 - 2000<br />

In 1960, roughly a decade after Sydney Poitier’s career began<br />

in earnest, and less than 10 years before Julia hit the airwaves,<br />

the rate of homeownership for African Americans was 38%. Of<br />

course there were reasons behind the number. First, the New<br />

Deal and the GI Bill, the two major American wealth-building assistance<br />

programs that bookended the Second World War, largely<br />

excluded Black people, as had all of the programs that preceded<br />

them. Throughout the '50s, Urban Renewal programs and the<br />

Federal-Aid Highway Act destroyed many Black neighborhoods,<br />

displacing hundreds of thousands of families nationwide. But<br />

perhaps even more impactful than these assorted causes was the<br />

systemic discrimination of redlining and race covenants — legal<br />

clauses enjoining Black Americans from owning or even inhabiting<br />

properties that included them in the deeds. Race covenants in<br />

particular prevented African Americans from homeownership in<br />

desirable locations such as the many single-family developments<br />

in suburban neighborhoods being built to house the nation’s<br />

newly minted middle class.<br />

Much of that changed with the signing of Title VIII of the 1968<br />

Civil Rights Act — better known as the Fair Housing Act — or at<br />

least it appeared to for a time. Among other things, the act put an<br />

end to race covenants and redlining, making it illegal to refuse<br />

sale of a home to a Black person on the basis of race. By 1980,<br />

the rate of Black homeownership had surged to more than 45%,<br />

achieving the smallest gap between white and Black homeownership<br />

rates the nation had ever seen. Similar advances in income<br />

20 aphrochic

THE BLACK FAMILY HOME<br />

22 aphrochic

and education were occurring at that point<br />

as well. But after 1980, the advancement<br />

largely halts. By 1990, the rate of Black<br />

homeownership had fallen to 43.3% and by<br />

1995 it was 41.9%. By the mid-90s, though<br />

representation was hitting all-time highs,<br />

including depictions of the Black family<br />

home, by the end of the 20th century Black<br />

homeownership was headed back to some<br />

familiar lows.<br />

The Reversal: 2000 - 2019<br />

The divergence between the availability<br />

of Hollywood film and television roles<br />

for Black actors and rate of homeownership<br />

flipped in the early years of the 21st<br />

century. To begin with, on-screen opportunities,<br />

particularly on television dropped<br />

off significantly before 2010. According to<br />

a 2019 study by the University of Illinois,<br />

between 2001 and 2008 the proportion of<br />

Black actors in television roles slipped from<br />

an already paltry 17% to just 12%. Meanwhile<br />

by 2004, Black homeownership rates had<br />

surpassed 49%, a steady growth from 1995<br />

that reflected the targeting of Black prospective<br />

homeowners by predatory lenders<br />

pushing subprime mortgages. The Great<br />

Recession, which included the market crash<br />

of ’08, was built on the foundation of these<br />

loans, with the result that the inevitable<br />

downturn they caused wiped out more than<br />

50% of the median wealth of Black households<br />

and a staggering number of Black<br />

homes. In the wake of the recession, Black<br />

homeownership rates fell, reaching 46% by<br />

the end of the recession in 2009. But unlike<br />

white households, which had lost only 17%<br />

of their wealth and whose homeownership<br />

rates were actually on the rise by the end of<br />

the recession — reaching 75% by the end of<br />

2009 — Black homeownership and median<br />

wealth both continued to plummet. By 2019,<br />

only 40.6% of Black households owned a<br />

home, a rate virtually identical to where<br />

the country had been in the early '60s. The<br />

first 20 years of the 21st century effectively<br />

erased all of the progress of the previous 32<br />

years, from the signing of the Fair Housing<br />

Act to the turn of the century.<br />

Representation and Homeownership<br />

Since 2020<br />

2020 was a turbulent year, one the<br />

effects of which we are still trying to gauge<br />

and deal with years later, and with which<br />

we will likely continue to struggle with for<br />

years to come. That year marked both the<br />

beginning of the still-ongoing COVID-19<br />

crisis and the global expansion of the BLM<br />

movement through protest marches held<br />

in the wake of the police-slayings of George<br />

Floyd and Breonna Taylor. Both would leave<br />

their mark on Black representation and<br />

Black homeownership.<br />

As marches and protests mounted, international<br />

support for Black Americans<br />

poured in throughout the year. <strong>Issue</strong>s<br />

of Black safety and police violence were<br />

brought to the fore in America and<br />

elsewhere and were met with rising<br />

attention to issues facing Black Americans<br />

in other facets of life. Calls to defund the<br />

police and statistics-based arguments for<br />

the fundamental danger police forces pose<br />

to Black and other American communities<br />

were quickly joined and in some cases overshadowed<br />

by calls to support Black businesses,<br />

increase Black wealth and support<br />

greater representation, not only in film and<br />

television but in corporate America as well.<br />

Responses to this sudden attention,<br />

which some hailed as a renewing of the Civil<br />

Rights Movement, took a number of forms.<br />

As the year progressed, many actions, such<br />

as posting black squares on social media<br />

or creating multiple lists of Black businesses,<br />

came to be known as “performative<br />

allyship” — actions more effective at<br />

allowing white people to reassure themselves<br />

that they were not a part of the<br />

problem than at addressing the problem<br />

itself. Other actions, however, seemed more<br />

promising at the time.<br />

Between May and September of 2020,<br />

the number of job positions in DEI — the<br />

department of many companies tasked<br />

with addressing workplace injustices and<br />

ensuring a safe and equitable environment<br />

— increased by 123%. It surged another 23%<br />

between the <strong>No</strong>vembers of 2020 and 2021. At<br />

the same time, Black representation in film<br />

and television was matching the growing<br />

visibility of the community in social consciousness<br />

that year.<br />

In comparing the 18 months that<br />

preceded the declaration of the COVID-19<br />

pandemic and the 18 months that followed<br />

its nominal ending, Variety Business Intelligence<br />

found that 70.5% of television<br />

series released during what they term “the<br />

pandemic period” (April 1, 2020, to October<br />

1, 2021) featured a Black series regular — a<br />

65.8% increase from less than two years<br />

before. The number of films released with<br />

Black cast members also increased to 58.7%<br />

from 56.1%. Likewise, according to statistics,<br />

the early days of the pandemic had a<br />

beneficial effect on rates of Black homeownership<br />

as well — despite the usual<br />

obstacles.<br />

Zillow reports that in 2020 Black home<br />

loan applicants met with rejection at a rate<br />

84% higher than white applicants in the same<br />

year. Nevertheless, from its 2019 low of 40.6%,<br />

the rate of Black homeownership exploded,<br />

reaching a peak of 47% by the second quarter<br />

of that year. The upward trend would prove<br />

short-lived however, as by the end of 2020 the<br />

rate had dropped to 44.1%, and then to 43.1%<br />

by the end of 2021. Despite the hardships of<br />

COVID, however, white homeownership had<br />

reached a rate of 74.4 by that time. The 31.3%<br />

disparity between those numbers represents<br />

the largest gap the nation had seen since<br />

issue fifteen 23

THE BLACK FAMILY HOME<br />

1890. While Black homeownership rates had rebounded to 45.9% by<br />

the end of 2023, with white rates of ownership dropping to 73.8%,<br />

the 27.9% disparity was still larger than the 26.2% that separated<br />

Black and white homeowners in 1960, almost a decade before the<br />

Fair Housing Act would be signed.<br />

Making Sense of it All<br />

So what does all of this tell us? Actually, not much. There are<br />

numerous factors not included in this brief consideration that<br />

impact and determine increases and decreases in pop media<br />

representation and rates of homeownership. Without including<br />

them, there is little that we can definitively say about what either<br />

actually means, much less determining whether one has any real<br />

impact on the other. All we can definitely say is that they are not<br />

the same thing — and that, ultimately, is the point.<br />

Increases in representation are part of the work of progress,<br />

but representation is not the whole of what’s needed, nor can it be<br />

considered an accurate barometer for where we currently stand<br />

as a people. Through the few decades included in this article, rates<br />

of representation and homeownership varied wildly and frequently<br />

diverged. In those few years where they did follow similar<br />

trajectories, one seems invariably to change course before the<br />

other, a phenomenon that can cause dissonances in our understanding<br />

of where we are and what we need to focus on, even<br />

within the issue of representation itself.<br />

While Black TV and film roles skyrocketed in 2020, in the<br />

same year a UCLA study found that 92% of studio heads were<br />

white. Similarly a McKinsey & Co. study found that between<br />

20<strong>15</strong> and 2019, Black people accounted for only 6% of Hollywood<br />

directors and producers, and a scant 4% of writers. This again<br />

shows how increases in visibility can belie continued marginalization<br />

in other areas. And while this can be problematic for a<br />

single industry, it can be disastrous when expanded across the<br />

idea of progress as a whole.<br />

For example, rising representation in the '80s and '90s<br />

masked stagnating progress in housing and income. Meanwhile,<br />

rising representation of Black businesses on social media in 2020<br />

masked the loss of more than 40% of Black businesses in that<br />

same year, along with racially disparate allocation of government<br />

support funds. So while the internet and social media was<br />

being flooded with lists of Black businesses for aspiring allies<br />

to support, amid cries to increase the development of wealth in<br />

the Black community, nearly half of existing Black businesses<br />

were closing their doors while banks and other lenders either<br />

excluded Black business owners from grant and loan programs<br />

or targeted them for predatory terms. Similarly the SAG-AFTRA<br />

strike revealed deep disparities in actor opportunities and<br />

wages on the back of a major increase in Black roles, and just<br />

ahead of a projected downturn in Hollywood production, leaving<br />

us to wonder what roles will be cut first on and off screen when<br />

Hollywood tightens its belt.<br />

The last thing that we can definitively say, is that none of<br />

this should be taken to denigrate or detract from the importance<br />

of representation. Representation is vital for many reasons,<br />

the simplest of which being that we are a part of this nation and<br />

the world, and deserve to be seen, and even more so, recognized<br />

as such. But as the argument for representation continues to be<br />

adopted and employed outside of our community — and reflected<br />

back to us — it is important to distinguish representation as the<br />

simple act of being visible or “seen,” from the recognition of Black<br />

dignity and humanity that we actually seek.<br />

In terms of simple visibility, Black people have never lacked<br />

for the attention of the nation. Even now, whenever the nation<br />

needs someone to arrest, imprison, lay off, or deem essential, it<br />

never seems have a hard time finding us. Conversely, recognition<br />

is the acknowledgement of our place, both in history and in society<br />

today. It works to be inwardly honest rather than outwardly acceptable,<br />

reflecting our humanity in its entirety, rather than artificially<br />

reducing our experience to fit the expectations of those<br />

who do not share it. It’s the kind of visibility that’s being denied<br />

when Black representation is lacking in both the cultural products<br />

that shape and enshrine our concept of history and the industries<br />

that produce them. It’s the kind of recognition that we build for<br />

ourselves in the design of our homes and in our connection to them.<br />

Increases in that kind of recognition, that doesn’t come with<br />

stereotypes, caricatures, or being forced to conform to the expectations<br />

of any kind of external gaze can always change the game —<br />

but they aren’t the whole game. So more Black shows, new Black<br />

movies, and Black-led halftime shows are all needed and rightfully<br />

celebrated. Yet in those moments when they come, we should<br />

also ask ourselves how what’s appearing on screen compares with<br />

what’s happening in our communities, and where else we need<br />

to focus to build an equitable and just home in America where<br />

progress and representation are more than a passing trend. AC<br />

24 aphrochic

MOOD<br />

Weave<br />

Across the African Diaspora, weaving has<br />

always been a medium for telling our stories.<br />

Whether weaving hair, quilts, clothing,<br />

or rugs, in the Americas, the Caribbean,<br />

and on the Continent, weaving has been<br />

more than just hobby or craft. Textiles<br />

are a deep part of our cultural legacy; our<br />

ancestors weaving canvases with purposeful<br />

intention, meaningful messages, and<br />

sometimes the very keys to our liberation.<br />

In Hidden in Plain View: A Secret Story of<br />

Quilts and the Underground Railroad, the authors<br />

trace the history of weaving quilts as<br />

a form of activism for Black Americans. In<br />

the 19th century, quilts hung outside homes<br />

were embroidered with coded messages. A<br />

log cabin in a quilt meant "seek shelter now,<br />

the people here are safe to speak with," and<br />

acted as maps for those forging their own<br />

roads to freedom. Today, textile artists like<br />

Bisa Butler and Billie Zangewa, both part<br />

of the Spelman College Museum of Art’s<br />

new exhibition Threaded, use textiles to<br />

help us remember who we are, weaving old<br />

and new stories that explore our past, our<br />

present, and that dream of our future. And<br />

in the world of home decor, a new generation<br />

of artists and product designers, from<br />

Yinka Ilori to Aliyah Salmon, are creating<br />

woven rugs as art that expresses Black life<br />

in the 21st century. Pieces that we can add<br />

to our own homes, honoring our cultural<br />

heritage and woven legacy.<br />

Curves by Sean Brown<br />

Multicolor Archway Door<br />

Mat $<strong>15</strong>0<br />

ssense.com<br />

Amechi Mandi Spill<br />

Rug $1,562.31<br />

floorstory.co.uk<br />

Jensin Okunishi Studio<br />

Moon Pools Rug<br />

aphrochic.com<br />

contact for price<br />

26 aphrochic

Ananda Natural<br />

Pop Rug $419<br />

ruggable.com<br />

Faatimah Mohamed Luke<br />

Coir Door Mat $6.92<br />

mrpricehome.com<br />

Justina Blakeney X Loloi<br />

Villagio Area Rug, starting at<br />

$51.92 wayfair.com<br />

Eva Sonaike<br />

Copper Batik Rug<br />

$1,945<br />

evasonaike.com<br />

Little Wing Lee<br />

Echoic Rug<br />

verso.nyc<br />

contact for price<br />

Yinka Ilori Omi<br />

Rug $1814.49<br />

yinkailori.com<br />

Punch Needle<br />

Textile Art by Aliyah<br />

Salmon<br />

aliyahsalmon.com<br />

contact for price<br />

issue fifteen 27

FEATURES<br />

A World Within Itself | A Mid-Century Modern Dream | Art for the People |<br />

Soul Ramen | The Joy of Spring | Exploring Black History in the City of<br />

Brotherly Love | Radically Reimagined | A Better Life | BLKBOK

Fashion<br />

A World<br />

Within Itself<br />

Where East Meets West in the Diasporic Expression<br />

by Fashion Brand Kwasi Paul<br />

Embracing the in-between can feel uncomfortable for many. However, fashion<br />

brand Kwasi Paul thrives in the unknown; weaving its own identity and building<br />

a world that lives at the intersection of Eastern and Western worlds within the<br />

African Diaspora.<br />

The essence of the brand transcends borders, with its unique narrative that<br />

draws from the past and embodies the spirit of "future ancestors.” In the brand's<br />

latest collection, Market Symphonies, “the symphonic juxtaposition of an African<br />

Market in a foreign world” is explored. The collection is a captivating array of<br />

menswear and womenswear masterpieces that double as wearable art. The<br />

brand offers a kind of parallel between modernity and tradition with timeless<br />

cuts, precise tailoring, and striking cultural embellishments. Details such as<br />

people, spices, peppers, and cowrie shells, converge to represent the soul of the<br />

African Market.<br />

Interview by Krystle DeSantos<br />

Photos by Kwasi Paul<br />

30 aphrochic

Fashion<br />

The creative direction is a stroke of<br />

genius. Photo shoots in iconic New York City<br />

locations like Keita West African Market in<br />

Brooklyn and the Shabazz Market on 116th<br />

Street in Harlem, remind us that shared<br />

connections and community transcend<br />

physical boundaries. The brand explores<br />

the unique blend of culture and tradition,<br />

while embracing self-expression as well<br />

as fluidity in who gets to wear what. To<br />

complete the experience of this collection,<br />

there is a complementary Spotify playlist,<br />

Sounds of Kwasi Paul Vol II: Market Symphonies,<br />

where you can immerse yourself<br />

further into this vibrant world.<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong> sat down with Creative<br />

Director Sam Kwabena Boakye to discuss<br />

the brand further and learn more about<br />

what the future holds for Kwasi Paul.<br />

AC: Could you bring us into the world<br />

of Kwasi Paul? What would someone who's<br />

not familiar with the brand experience upon<br />

entering this world?<br />

SB: It's funny that you use the term<br />

world because I feel like Kwasi Paul is a<br />

world within itself, created by two distinct<br />

worlds. Sometimes I like to describe it as<br />

a world that was created from the debris<br />

of the Western world and the African<br />

Diaspora world. I say that because I draw<br />

my inspiration from both worlds, having<br />

been first-born generation. I was raised<br />

in a household where in one situation, everybody's<br />

speaking your native language,<br />

listening to the native music, and eating<br />

native foods. Then as soon as you step out<br />

of that household, you're introduced into<br />

the Western world. It was always a back<br />

and forth, so I pull a lot of inspiration from<br />

my experience, being raised in that in-between<br />

space where the African and Western<br />

worlds come together.<br />

AC: Tell me more about your backstory<br />

as well as your experience growing up in<br />

America. How did that inspire and influence<br />

Sam Kwabena Boakye<br />

your journey to becoming the Creative<br />

Director of Kwasi Paul?<br />

SB: Absolutely! My parents are from<br />

Ghana, West Africa, and were raised in a<br />

village called Mampong that's located in the<br />

Ashanti region, not too far from Kumasi.<br />

I was born in the Bronx, but was also<br />

raised in LeFrak City, Queens, two areas<br />

where culture is very distinct. If you know<br />

anything about the Bronx, sometimes it’s<br />

also referred to as Little Accra because if<br />

you're coming from Ghana and relocating<br />

to the States, you'll probably end up in the<br />

Bronx or in LeFrak City, where there's also<br />

a heavy Ghanaian community. Both areas<br />

also have really strong Black cultural connections<br />

tied to them; such as the Bronx<br />

being the birthplace of Hip Hop. I was<br />

obviously exposed to all of that, but then<br />

I was also exposed to Ghanaian culture<br />

within the household, as my parents tried<br />

their best to keep that prevalent.<br />

There are some challenges that<br />

come with being the first-born generation<br />

too, sometimes you feel like you're not<br />

fully accepted in one culture or the other.<br />

Growing up in the West, we heard derogatory<br />

terms like "African booty scratcher,"<br />

people messing up your last name, or having<br />

this negative depiction of what Africa looks<br />

like. But on the other hand, when I visit<br />

Ghana, some think I'm like an alien and<br />

might even say things like, “We know you're<br />

not from here, your skin is different” or I<br />

would be made fun of when I tried to speak<br />

the language because I wasn’t as fluent or<br />

my sound was different. This is probably the<br />

reason why I don't speak it as much now, but<br />

I understand everything.<br />

These were some of the experiences<br />

that shaped who I am today and though<br />

it sometimes feels like I don't fully belong<br />

in one world, there is a positive perspective<br />

in that I'm from both worlds and I’m able to<br />

navigate through both, taking on so much<br />

from both cultures and making it my own!<br />

Whether it’s music, art, or fashion, I am able<br />

to make more of a correlation between both<br />

worlds compared to somebody that's from<br />

one, who has just seen it from one perspective.<br />

AC: What sense of responsibility do you<br />

feel towards both communities?<br />

SB: Sometimes within our communities<br />

there tends to be a kind of separation<br />

between African-American culture and<br />

culture within the African Diaspora, but<br />

I think one of the great things about being<br />

born in between is that we hold the key. We<br />

are able to be a bridge for sharing ideas and<br />

bringing us together.<br />

I think that as first-born generations or<br />

people that just moved to a different world,<br />

it's our responsibility to create that connection<br />

because we're better as a community,<br />

we're better as a group, and we're stronger.<br />

In my stories, I’m trying to portray this<br />

sentiment while also trying to educate and<br />

teach people through my collections and<br />

32 aphrochic

issue fifteen 33

Fashion<br />

I think many from the Diaspora can relate in some way. In<br />

my recent Market collection, there are images with Milo in<br />

the background and you don't have to be Ghanaian to understand<br />

the importance of drinking Milo in the morning, you<br />

know what I'm saying? You could be from Trinidad, Jamaica,<br />

or Guyana, and understand how important that is and feel<br />

that connection. When you look at our editorials, you don't<br />

have to be taught why someone is braiding hair in somebody's<br />

kitchen. You could be from Ghana, the Caribbean, or even the<br />

South, and this is something that's prevalent in a lot of our<br />

families and communities. Being able to tell these stories and<br />

have so many people talk about it and say, “oh my gosh, I went<br />

through that same thing,” is a start in building that bridge<br />

and connection.<br />

AC: With your visuals and designs, there is a noticeable<br />

vintage/retro vibe. What is the creative stylistic choice behind<br />

that aesthetic and how does this ultimately influence your<br />

design decisions?<br />

SB: I love nostalgia and living in the past. Recently<br />

I’ve been watching re-runs of the sitcom A Different World.<br />

Sometimes it feels like the world is moving so fast and I loved<br />

that show when I was growing up in the early '90s. Re-watching<br />

it now creates nostalgia for a time of innocence in my<br />

life, when I didn't have to worry about looking after myself,<br />

and I’m trying to recreate that feeling of nostalgia with my<br />

visuals.<br />

Growing up, I also enjoyed watching my uncles and<br />

aunts get dressed up to go to parties and events and even<br />

looking back at my family's photo albums, I’m able to draw a<br />

lot of inspiration from what was happening or taking place in<br />

the '70s and '80s before I was born. I use that mix of inspiration<br />

when it comes to the craftsmanship, the silhouettes that<br />

we create, and designs that we do. Even with our storytelling<br />

those influences are strong and were very prevalent in one<br />

of our very first collections, From Gold Coast to East Coast. I<br />

took complete inspiration for that collection from my parents'<br />

photo albums and experiences from growing up as well.<br />

AC: You referenced the world feeling like it’s moving so<br />

fast right now and we tend to see that reflected in the fashion<br />

industry as well. However, Kwasi Paul’s approach to designing<br />

collections is distinctive. What do you feel sets you apart from<br />

other designers?<br />

SB: I'll try to be as transparent as possible. All I'm really<br />

doing is telling a story through my own lens. There are a<br />

lot of other great designers that tell very similar stories,<br />

for example you have Wales Bonner, who’s telling it from a<br />

Caribbean/UK perspective and I’m telling it from the perspective<br />

of a Ghanaian, who was born in the Bronx, raised in<br />

LeFrak City with roots from the Ashanti region. I really try<br />

to tap into those unique elements, leveraging the history that<br />

exists in those regions while intertwining them into my own<br />

expression; which is going to be different when compared to<br />

someone else.<br />

I also try to look at other mediums of communication<br />

and how we can evoke emotions within the storytelling of<br />

each collection. I never want to just spitball history facts or<br />

information, but I aim to understand how we communicate<br />

history, through music, movement, sound; through the<br />

senses, whether it's taste or touch. I think this also separates<br />

us from other brands. For example, the Milo beverage would<br />

be an example of communicating through the senses of<br />

sight and even taste. As soon as you see it, you think, “Oh, I<br />

remember how good Milo tasted back in the day.” Or with the<br />

African Market, you can remember what it feels like, walking<br />

into the market and recall the smells of spices.<br />

AC: I love that perspective and sensory experience! While<br />

we’re on the topic of design, you’re primarily a menswear brand<br />

but there is fluidity with your clothing, where anyone can appreciate<br />

and even wear the pieces. Is that intentional as part of<br />

the design process?<br />

SB: To be honest, it's actually not intentional. I attended<br />

LATTC in Los Angeles for menswear tailoring so I start with<br />

menswear because that is my background. And then growing<br />

up I was a church boy, so I wore suits every Sunday.<br />

I also just love the way menswear looks on women, so<br />

the way I design, it really does come off as fluidity and things<br />

of that nature. I take a lot of inspiration from back in the day,<br />

when clothing was also very fluid, like in the '70s, with both<br />

men and women wearing bell bottoms and crop tops. Part of<br />

Kwasi Paul is just ongoing research, trying new things, and<br />

cultivating creativity.<br />

AC: Speaking of cultivating creativity and trying new things,<br />

there is mention of The REVIVAL Mission on your website. What<br />

is that and what can we expect from that initiative?<br />

SB: We've been working on that initiative for a long time,<br />

since the inception of Kwasi Paul. I have a friend, Yayra, who<br />

is based out of Ghana, and he’s in an area called Kantamanto,<br />

which is the largest secondhand fashion market in Ghana.<br />

And as a designer, I feel like there should be a sense of responsibility<br />

coming into this world because, in full transparency,<br />

fashion is responsible for a lot of pollution that happens there.<br />

So with The REVIVAL mission, we’re looking to do some type<br />

of collaboration, whether it's through textile, whether it's<br />

through design, or even just giving proceeds to The REVIVAL<br />

mission that he has there.<br />

What he's looking to do is pretty much take second-<br />

34 aphrochic

Fashion<br />

36 aphrochic

issue fifteen 37

Fashion<br />

hand fashion to another level and turn the city of Kantamanto<br />

around, from the depiction of it being just a hub for brands<br />

to dump their pieces or bootlegs, and turn it into a design city.<br />

We talk like once every three months and we're like, “Yo, s'up,<br />

let's do something.” I literally just spoke to him today so I'm<br />

hoping that maybe by 2025 we can do a collection that introduces<br />

the upcycling aspect to Kwasi Paul and have that be<br />

really authentic and organic and somehow implement that<br />

within our processes and then also help build Kantamanto.<br />

I told him, I'd love to one day make Kantamanto look like<br />

the Rodeo Drive of Beverly Hills without having to gentrify<br />

it and make sure that it's actually going to benefit the people<br />

that live in that area, bringing money to the area so it can be<br />

built up and not looked at as a fashion dump. One of my goals<br />

is not just to design clothes, but I also want to design worlds<br />

and places, hence “the world” of Kwasi Paul.<br />

In addition to The REVIVAL being this kind of upcycle<br />

organization, they also have a mini brand as well and it’s<br />

called The Revival Earth by Yayra Agbofah. Check them out!<br />

AC: I’m really excited to see that collaboration come to<br />

fruition by 2025 and as we look to the future, what’s on the<br />

horizon for Kwasi Paul?<br />

SB: I have a new collection coming up called Black Star<br />

Groove that's going to be a very fun collection. It's sort of like an<br />

ode to Hiplife, which is pretty much a musical genre that came<br />

about in Ghana, inspired by Highlife, but influenced by Hip<br />

Hop. It serves as a sense of freedom, going against the norm and<br />

is an era I grew up in. Artists like Daddy Lumba, Kojo Antwi,<br />

VIP and Ofori Amponsah were played in my household and it<br />

was also very prevalent within the Y2K era, when we saw a shift<br />

in style with a lot of denim being worn, Bluetooth headsets,<br />

baggy jeans and jerseys. Have you heard of <strong>No</strong>llywood? It's the<br />

Nigerian version of Hollywood where that style was also very<br />

prevalent in the movies around that time.<br />

With this new collection I’m trying to bring those<br />

elements to life within the brand while still keeping hints<br />

of the '70s and '80s with the cuts and things of that nature,<br />

but we will be playing with denim this time, curating that<br />

with Fugu and Kente textiles from Ghana. There will also be<br />

pinches of plant-based leather and then the styling will be a<br />

little bit newer than what you've seen before.<br />

We will also be dropping an accompanying four-track<br />

EP that is influenced by that genre. It will be the sounds of<br />

Kwasi Paul for the Black Star Groove collection and we’re<br />

working to decipher what that sound looks like now and in<br />

years to come. I'm actually having producer Nana Kwabena<br />

from Wonderland Label, who’s worked very closely with<br />

artists like Janelle Monae and Jidenna, curate four tracks with<br />

artists and producers that we're cool with. It's going to be a<br />

fun and very eclectic collection. AC<br />

38 aphrochic

issue fifteen 39

Interior Design<br />

A Mid-Cen

tury Modern Dream

Interior Design<br />

Inside Brazilian Interior Designer<br />

Ana Claudia Schultz’s Upstate New York Home<br />

Ana Claudia Schultz has an eye for good design. Born in Brazil and<br />

raised in Miami, the designer made the move from her Brooklyn<br />

apartment to her first home in the idyllic town of Hyde Park, N.Y., in<br />

the mid-2010s. Just two hours north of New York City, the space she<br />

lovingly refers to as her “forever home” sits with a sparkling view<br />

of the Hudson River in front and a lush canopy of trees in the back.<br />

The home features striking mid-century modern architecture and<br />

a brick red exterior. Inside, layers of unique elements work together<br />

effortlessly, guided by Ana Claudia’s confident designer’s eye.<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Photos by Chinasa Cooper<br />

issue fifteen 43

Interior Design

Interior Design

Interior Design

Interior Design<br />

Everything in the interior was thoughtfully<br />

designed by Ana Claudia and her husband<br />

Aaron. On the wall, sketches of the home’s<br />

original design have been framed, a testament<br />

to how far the interior has come. Ana Claudia<br />

and Aaron took on the full-scale renovation,<br />

bringing a 4,000-square-foot-home that was<br />

originally built in the 1950s, solidly into the 21st<br />

century. “We pretty much gut renovated most<br />

of the house,” says Ana Claudia. “The upstairs<br />

kitchen, a totally new dining room, we opened<br />

up the space, removed some stone work that<br />

was on the fireplace to open that up so that we<br />

get a nice amount of sunlight everywhere. We<br />

transformed the mudroom and a downstairs<br />

bathroom, and we reconfigured the master<br />

bathroom.”<br />

The home’s open plan living room is<br />

bathed in sunlight. Airy and refreshing, windows<br />

look out onto the river, framing the peaceful<br />

tableau. Designed to easily seat 10 to <strong>15</strong> guests,<br />

a large sectional in the living room is situated to<br />

comfortably view the great outdoors. A second,<br />

streamlined sofa is featured alongside a vintage<br />

coffee table that Ana Claudia discovered. Two<br />

more vintage finds — Vernon Panton Flowerpot<br />

Lamps — add to the room’s color palette of<br />

black, blue, and red. “In my home I want to bring<br />

in things that I really love,” remarks Ana Claudia.<br />

“Things that tell a story. Even if we bought it at<br />

a vintage store that’s a story to us — of a local<br />

artist, or a place we visited.”<br />

The fireplace, an eyesore when the couple<br />

first bought the home, has been designed to<br />

make a bold statement, tiled to resemble the<br />

sidewalks of Copacabana in Rio de Janeiro. “It’s<br />

actually based upon a Portuguese pattern,” says<br />

Ana Claudia. “Landscape architect Roberto<br />

Burle Marx created the patterns in Rio. My<br />

husband asked if we could get the Copacabana<br />

tile and we found this cement tile and decided to<br />

put it on the fireplace.”<br />

In the dining room, seating reminiscent<br />

of George Nakashima’s Straight-Back Chair<br />

surrounds a traditional style dining table. The<br />

mix of influences, including a jaguar clay pot<br />

from Mexico, is a reflection of Ana Claudia’s love<br />

of art and design from various cultures. “I’m<br />

Brazilian, so culturally I bring in a little bit of<br />

the Brazilian culture. My husband is American<br />

and I grew up in America, too, so we bring in<br />

American design as well.”<br />

Through the dining room, the kitchen<br />

includes custom details that stand out as<br />

unique statement pieces. Chevron tile creates<br />

a graphic display as the backsplash behind<br />

the range. And at the center of the kitchen, an<br />

island has been designed that blends stone and<br />

natural wood in an unexpected way. The mix of<br />

materials adds to the home’s story of mid-century<br />

modern design that’s also personal and<br />

outside of the box. “In Brazil mid-century<br />

was so integrated into a lot of the architecture.<br />

You might live in a mid-century home, but<br />

you would have things of the past present in it<br />

— your grandmother’s doilies, trunks passed<br />

down from family members. So we took cues<br />

from that and felt very comfortable making this<br />

home bold and personal to us.”<br />

An eye for discovering unique vintage<br />

pieces, Ana Claudia’s talent is on display in the<br />

home’s main bedroom. Two unique side tables<br />

blend mid-century style with eclectic craftsmanship,<br />

as figurative art has been sculpted<br />

into each table’s design. A large-scale dresser,<br />

also vintage, is topped with a collection of vases<br />

and plants that have a backdrop of the lush<br />

landscape that surrounds this upstate home.<br />

The room’s pièce de résistance is a mural<br />

designed by Ana Claudia and installed by a local<br />

artist. The abstract design is repeated in painted<br />

lamp shades on the bedside tables. “Artwork<br />

is very important for your home,” says Ana<br />

Claudia. “I like art that’s not about trends, but<br />

that speaks to the heart.”<br />

A walk down the stairs and you enter the<br />

lower level of the interior. Built for family gatherings,<br />

Ana Claudia has created unique spaces<br />

for restful retreats in every nook. Just below<br />

the staircase a reading nook has been carved<br />

out. Favorite books are on display along with a<br />

collection of plants nurtured by Ana Claudia’s<br />

green thumb. A windsor chair invites visitors<br />

to take a seat and read a good book. And in the<br />

family room a mid-century modern console<br />

doubles as a bar cart for entertaining.<br />

This “forever home” designed by Ana<br />

Claudia and Aaron is filled to the brim with<br />

personal style, eclectic belongings, and pieces<br />

that tell their story. "There's pieces from my<br />

family in Brazil: a coffee grinder that belonged to<br />

my grandparents; cowhide trunks that belonged<br />

to cattle farmers in my dad’s family, a painting<br />

by a friend that has moved with me over the<br />

years and now sits in our dining room. There's<br />

even a model from my architectural school days<br />

— things that I really love, that tell a story, that<br />

bring soul to this house." AC<br />

issue fifteen 49

Interior Design

issue fifteen 51

Interior Design<br />

52 aphrochic

issue fifteen 53

Interior Design

Culture<br />

Art For The People<br />

Adams, Woman in Grayscale (Alicia)<br />

56 aphrochic

Adams, Man in Grayscale (Swizz)<br />

issue fifteen 57

Culture<br />

Inside The Dean Collection at the Brooklyn Museum<br />

On a Saturday night in Februar y, one of the most signif icant art exhibitions<br />

of the 21st century opened at the Brooklyn Museum — Giants: Art from<br />

the Dean Collection of Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys. Featuring 98 major<br />

artworks by artists from across the African Diaspora, the international<br />

show includes works by legendary artists, pieces that expand the canon<br />

of contemporary art, and monumental efforts by artists who are shifting<br />

the landscape of the art world.<br />

.<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays<br />

Photos furnished by the Brooklyn Museum<br />

Spann, Basking in the Wind (left)<br />

58 aphrochic

ELEVATING THE<br />

Conversation<br />

JEANINE HAYS AND BRYAN MASON, AUTHORS<br />

OF APHROCHIC: CELEBRATING THE LEGACY OF<br />

THE BLACK FAMILY HOME, JOIN THE TOP<br />

LITERARY THOUGHT LEADERS AT THE PENGUIN<br />

RANDOM HOUSE SPEAKERS BUREAU TO SPEAK<br />

ON TOPICS SURROUNDING BLACK CULTURE,<br />

HOUSING EQUITY AND THE SOCIAL IMPACT OF<br />

DESIGN IN AMERICA.

Culture<br />

The works presented in the exhibition<br />

are from a “who’s who” of the greatest and most<br />

discussed artists in the world today — Kehinde<br />

Wiley, Amy Sherald, Barkley L. Hendricks, Jamel<br />

Shabazz, Gordon Parks, Nina Chanel Abney,<br />

Toyin Ojih Odotula, and Nick Cave, to name a few.<br />

If you’re an art aficionado, the very idea of all of<br />

these incredible artists showing their work in a<br />

single exhibit gives you goosebumps. And if you’re<br />

a historian, the exhibition gives you pause, as<br />

there are just a handful of international exhibits<br />

that have existed that celebrate Black art in such a<br />

way. “The title Giants is so important, because the<br />

artists are giant,” reports Swizz.<br />

The Dean Collection itself has become<br />

a giant in the art world, founded by Kasseem<br />

Dean (Swizz Beatz) and Alicia Keys in 2014. From<br />

its inception, it was clear that the couple had a<br />

unique lens in the art world. They weren’t interested<br />

in building a static collection to floss wealth,<br />

or gobbling up Black art and locking it away in<br />

warehouses. Instead, the Dean Collection was<br />

imagined as both a family collection and a cultural<br />

platform. One focused on supporting the careers<br />

of living artists, particularly artists of color, and<br />

democratizing art to make it accessible to all.<br />

Born and bred in New York City, with early<br />

roots in the music industry, it’s no surprise that<br />

these music icons have creatively thought outside<br />

of the box as art collectors. Hailing from the<br />

Bronx, Swizz became a producer for his family’s<br />

record label, Ruff Ryders, when he was only 17,<br />

while Keys, a <strong>15</strong>-time Grammy award winning<br />

artist, whose semi-autobiographical show Hell’s<br />

Kitchen recently opened on Broadway, has been<br />

making waves since dropping her debut album at<br />

the age of 20. Together, the two are blending their<br />

deep love of art and music with the Dean Collection.<br />

In 2016, they launched <strong>No</strong> Commission. The<br />

immersive art and music experience started in<br />

the South Bronx with a distinctive concept. People<br />

from the community could come to a festival, ride<br />

a ferris wheel, listen to local musicians like A$AP<br />

Rocky and Cardi B, and walk through an extraordinary<br />

gallery located in an on-site warehouse<br />

showcasing works by artists like Delphine<br />

Diallo, Jerome Lagarrigue, and Jeffrey Gibson.<br />

<strong>No</strong> pretense, no fuss, just fun. Artists were in the<br />

room, Swizz was in the DJ booth, and the Dean<br />

Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys<br />

Hendricks, Rainbow Sky at Sunset<br />

60 aphrochic

Patterson, ...they were just hanging out you know...talking about... (...when they grow up...)<br />

Collection had successfully taken art outside of<br />

the world of downtown white box galleries and<br />

returned it to the people.<br />

In addition to being a fun event, <strong>No</strong> Commission<br />

represented a revolutionary new idea<br />

in the art world. The artists who participated in<br />

the global event that traveled to Miami, London,<br />

Berlin, and Shanghai, were able to keep 100% of<br />

the proceeds from the works they sold, putting<br />

millions of dollars directly into the hands of living<br />

artists, something deeply important to the Deans.<br />

“I'm a producer, I'm a songwriter. Every time it's<br />

played on the radio, I get paid. Every time it's<br />

played in a movie, I get paid. Every time it plays,<br />

period, I get paid. Visual artists, they only get paid<br />

once,” Swizz stated in a discussion on supporting<br />

living artists with TED. “How, when paintings<br />

are sold and traded multiple times? And that's<br />

that artist's lifetime work, that other people are<br />

making 10, <strong>15</strong>, sometimes 100 times more than<br />

the artist that created it. So I created something<br />

called the Dean's Choice, where if you're a<br />

seller, or a collector, and you bring your work into,<br />

let's say, Sotheby's, there's a paper that's there<br />

that says, ‘Hey, guys, you know, this artist is still<br />

living. You've made 300% on your investment by<br />

working with this artist. You can choose to give<br />

the artist whatever you want of the sale.’ It'll start<br />

to change everything in the arts.” And it has. In<br />

2018, Swizz was part of the sale of Kerry James<br />

Marshall’s, Past Times (1997). The piece sold for<br />

$21.1 million at Sotheby’s, making Marshall the<br />

highest-selling, living African American artist to<br />

date.<br />

In May of 2018, the Dean Collection made<br />

another stunning move in the art world. Swizz and<br />

Alicia announced the acquisition of more than 80<br />

photographs by famed photographer Gordon<br />

Parks. The landmark acquisition of works by one<br />

of the greatest photographers of the 20th century<br />

included important archives of Black history —<br />

photographs of Malcolm X, Rosa Parks, Langston<br />

Hughes, Muhammad Ali, as well as images of<br />

Black life in the rural south during Jim Crow, on<br />

the streets of Harlem, and in the favelas of Rio de<br />

Janeiro. The acquisition was also an important<br />

showcase of something that is not seen often —<br />

Black collectors being able to collect Black art.<br />

issue fifteen 61

Culture<br />

“The collection started not just because we’re<br />

art lovers, but also because there’s not enough<br />

people of color collecting artists of color,”<br />

Swizz told Cultured magazine in 2018.<br />

In 2019, the Dean Collection launched the<br />

exhibition, Gordon Parks: Selections From The<br />

Dean Collection at the Ethelbert Cooper Gallery<br />

of African & African American Art at Harvard<br />

University. “The Deans have been important<br />

champions of the work of Gordon Parks, and<br />

this exhibition is an opportunity to share his<br />

work with a broader audience through the outstanding<br />

platform offered by Harvard University,”<br />

Peter W. Kunhardt, Jr., Executive Director<br />

of The Gordon Parks Foundation stated at the<br />

time. “The exhibition additionally builds on the<br />

Foundation’s strong history of collaborative<br />

programming with leading institutions in the<br />

mounting of exhibitions, conferral of scholarships,<br />

and mounting of public programs that<br />

engage the public with Parks’ legacy.”<br />

Today, Swizz and Alicia are known not<br />

only for their music genius, but for their shared<br />

passion in collecting, supporting and building<br />

community among artists of color. And their<br />

Giants exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum is<br />

a testament to all that they have done and will<br />

continue to do to create an art world where<br />

Black artists can thrive. “Swizz Beatz and<br />

Alicia Keys have been among the most vocal<br />

advocates for Black creatives to support Black<br />

artists through their collecting, advocacy, and<br />

partnerships. In the process, they have created<br />

one of the most important collections of contemporary<br />

art,” notes Anne Pasternak, the<br />

Shelby White and Leon Levy Director of the<br />

Brooklyn Museum.<br />

Stepping into the exhibit, it’s clear that<br />

Giants is something special. It recalls past exhibitions<br />

at the Brooklyn Museum that have<br />

been central to it’s focus on expanding the<br />

art-historical narrative: Kehinde Wiley: A New<br />

Republic in 20<strong>15</strong>; We Wanted a Revolution: Black<br />

Radical Women, 1965-85 in 2017; and Soul of A<br />

Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power in 2018.<br />

Broken into five parts, the exhibition<br />

opens in “Becoming Giants” where viewers are<br />

introduced to Swizz and Alicia’s creative lives<br />

and their sources of inspiration. It then moves<br />

to “On The Shoulders of Giants” paying homage<br />

to legendary artists who have made their mark<br />

on the world — pieces by Esther Mahlangu,<br />

Kwame Braithwaite, and Gordon Parks are in<br />

conversation with Barkley L. Hendricks, Malick<br />

Sidibé, and Sanlé Sory. In “Giant Conversations”<br />

the artwork is focused on social critique,<br />

with the artists on view addressing a range of<br />

issues that Black people have faced throughout<br />

the 20th and 21st centuries.<br />

Nick Cave’s protective sound suits<br />

are presented along with Lorna Simpson’s<br />

collages focused on Black women’s self-representation.<br />

Viewers then explore giant conversations<br />

focused on celebrating Blackness.<br />

Jamel Shabazz’s street photography of 1980s<br />

New York City is exceptionally fly. And Amy<br />

Sherald’s colorful diptychs celebrating Baltimore’s<br />

dirt bike culture show a joyful<br />

freedom. And in the final stage of the exhibition,<br />

“Giant Presence”, you see awe-inspiring<br />

pieces by Nina Chanel Abney, Titus<br />

Kaphar, and Meleko Mokgosi, that use scale<br />

to emphasize powerful themes that resonate<br />

across history.<br />

But Giants does not end there. In keeping<br />

with the mission of the Dean Collection,<br />

pop-up talks that invite community engagement<br />

will be held throughout the exhibition’s<br />

run, and a special shop has been curated with<br />

accessible pieces by the artists showcased. A<br />

budding collector can take home a Giants exhibition<br />

poster featuring the work of Toyin Ojih<br />

Odotula, signed by the artist; pick up a limited<br />

edition bone china plate featuring the work of<br />

Henry Taylor; and order the accompanying exhibition<br />

catalog to be published by Phaidon in<br />

June.<br />

Giants is truly one of those once-in-alifetime<br />

exhibitions that changes the way you<br />

feel, experience and relate to art, understanding<br />

that art is not best when it’s closed off, but<br />

is most relevant when it’s among the people.<br />

“We want people to see themselves,” says<br />

Keys.“We want people to feel inspired. We want<br />