AphroChic Magazine: Issue No. 14

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

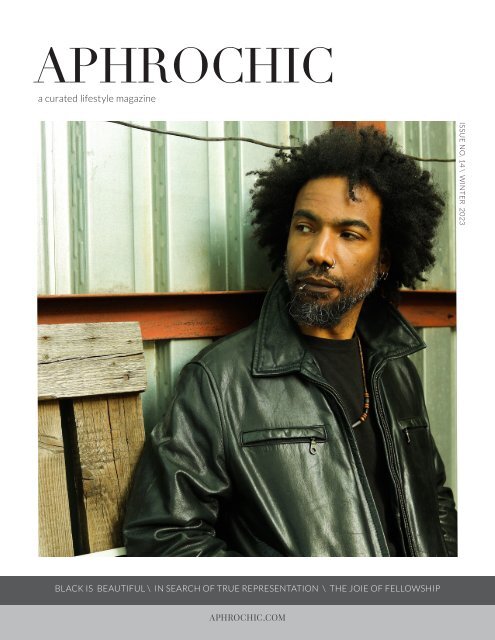

APHROCHIC<br />

a curated lifestyle magazine<br />

ISSUE NO. <strong>14</strong> \ WINTER 2023<br />

BLACK IS BEAUTIFUL \ IN SEARCH OF TRUE REPRESENTATION \ THE JOIE OF FELLOWSHIP<br />

APHROCHIC.COM

www.fisherpaykel.com

And just like that, we’re here at the end of another year. 2023 has been an amazing<br />

collection of highlights, firsts, and dreams come true. We never imagined the reception<br />

that APHROCHIC: Celebrating the Legacy of the Black Family Home would receive. After a<br />

10-month tour, we’ve spoken about the meaning of home to our community at the National<br />

Book Festival, The African American Museum in Philadelphia, The Free Black Women’s<br />

Library in Brooklyn, and at Harvard University.<br />

Thank you to everyone who has come to see us, and who have taken the time to share your story with us. Most of all, thank you<br />

to everyone who is taking this opportunity to grow the conversation, highlighting stories of our families and our homes in America’s<br />

history and bringing attention to the important role of homes and homeownership in the health and wealth of Black Americans.<br />

Beyond the book, 2023 marked the opening of the <strong>AphroChic</strong> Art Shop on Perigold and Wayfair. We are grateful to all of the<br />

incredible artists who have partnered with us, and everyone who has supported them. We look forward to growing the collection,<br />

and bringing this platform to more artists. And finally, 2023 marked the four-year anniversary of <strong>AphroChic</strong> magazine. We could<br />

not be more proud of this publication and the community it is building. We thank all of our readers for being part of the journey<br />

with us, celebrating the culture, history and diversity of our Diaspora and the endless sea of talent and creativity within it.<br />

In this issue, our cover story is a conversation with producer, emcee, and electronic music icon, Thavius Beck. The veteran of<br />

Project Blowed and Low End Theory walks us through his journey from 16-year-old battle rapper to electronic music pioneer to his<br />

current position as a professor for Berklee NYC. From there we take you to Casco Viejo, Panama, for a tour of the sights, sounds, pirate-filled<br />

history and must-try eateries of this Caribbean jewel.<br />

Taking a closer look at the first steps of the movement for diversity in the fashion industry and its next steps in the design<br />

industry, we look at Invisible Beauty, celebrating the career and impact of iconic model and agent, Bethann Hardison. We then<br />

explore the ups and downs of representation in the design industry from the perspective of Black students and professionals.<br />

In Interior Design, we invite you into the home of artist, Huda Hashim. The British-born, Sudanese designer’s four-bedroom<br />

Texas home is a mix of influences from around the world, highlighted with works from the artist’s own studio. Then we’re in the<br />

kitchen with Chef Kenny Gilbert, author of the new book, Southern Cooking, Global Flavors to taste his incredible, South American-inspired,<br />

Coffee-Rubbed Spareribs.<br />

Ajiri Aki introduces us to the sense of “Joie” (joy) that began for her in Texas and that stems directly from her Nigerian roots.<br />

And in this issue’s Hot Topic, we take time to appreciate our beloved aunties and uncles, looking at their place in the culture from<br />

African traditions to TV’s greatest, to the “Rich Aunties” and “Educated Uncles” of today. Finally, doctor of psychology, dancer and<br />

wellness guru Kimya Jackson reminds us of the power of dance and the importance of being at home in our own skin.<br />

It was an amazing year, and we’re ending it with an equally amazing issue. The new year and new possibilities are just around<br />

the corner. We can’t wait to see you there.<br />

Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Founders, <strong>AphroChic</strong><br />

Instagram: @aphrochic<br />

editors’ letter

WINTER 2023<br />

DEPARTMENTS<br />

Read This 10<br />

Visual Cues <strong>14</strong><br />

Coming Up 16<br />

The Black Family Home 18<br />

Mood 30<br />

FEATURES<br />

Fashion // Black Is Beautiful 38<br />

Interior Design // An Artistic Abode 46<br />

Culture // In Search of True Representation 60<br />

Food // A Culinary Journey 68<br />

Entertaining // The Joie of Fellowship 72<br />

City Stories // Panama's Rich History 78<br />

Wellness // A Home Within Ourselves 96<br />

Sounds // Journey Through Sound 102<br />

PINPOINT<br />

Artists & Artisans 110<br />

Hot Topic 116<br />

Who Are You? 122

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

Cover Photo: Thavius Beck<br />

Photographer: Monifa Perry<br />

Publishers/Editors: Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Creative Director: Cheminne Taylor-Smith<br />

Editorial/Product Contact:<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong><br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong>.com<br />

magazine@aphrochic.com<br />

Sales Contact:<br />

Ruby Brown<br />

ruby@aphrochic.com<br />

Contributor:<br />

Krystle DeSantos<br />

issue fourteen 9

READ THIS<br />

HOLIDAY<br />

BOOKS<br />

The pandemic may have started an increase in reading, but that trend<br />

hasn't slowed in the last few years. In fact, we're seeing a Renaissance<br />

in reading with even tech-obsessed Gen Z consuming print books at<br />

a huge rate. They've even fueled #BookTok on TikTok. In the last year,<br />

Black published authors have also increased by 20%, covering every<br />

category from cookbooks to fiction to YA. <strong>AphroChic</strong>'s founders have<br />

two published books, with another in the works, so we're definitely<br />

obsesssed with fabulous reads. Here are our selections for the best books<br />

to give friends and family over the holiday season — or to purchase for<br />

yourself. We've selected one favorite in the most popular categories,<br />

including a look at the Tulsa tragedy, LL Cool J's homage to Hip-Hop,<br />

and a retrospective of artist Hughie Lee-Smith's work.<br />

nonfiction<br />

Built from the Fire<br />

by Victor Luckerson<br />

Publisher: Random House.<br />

$18.99<br />

fiction<br />

The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store<br />

by James McBride<br />

Publisher: Riverhead. $18.99<br />

music<br />

The Streets Win: 50 Years of Hip-Hop Greatness<br />

by LL Cool J, Vikki Tobak, Alec Banks<br />

Publisher: Rizzoli. $49.50<br />

10 aphrochic

Celebrate Black homeownership and the<br />

amazing diversity of the Black experience<br />

with <strong>AphroChic</strong>’s newest book<br />

In this powerful, visually stunning book, Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason explore<br />

the Black family home and its role as haven, heirloom, and cornerstone of Black<br />

culture and life. Through striking interiors, stories of family and community,<br />

and histories of the obstacles Black homeowners have faced for generations,<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong> honors the journey, recognizes the struggle, and embraces the joy.<br />

AVAILABLE WHEREVER BOOKS ARE SOLD

READ THIS<br />

HOLIDAY<br />

BOOKS<br />

children's<br />

The Kindest Red<br />

by Ibtihaj Muhammad<br />

Publisher: Little, Brown.<br />

$15.84<br />

art<br />

Hughie Lee-Smith<br />

by Hilton Als, Steve Locke,<br />

Lauren Haynes, and Leslie<br />

King-Hammond.<br />

Publisher: Karma. $60<br />

young adult<br />

The Shadow Sister<br />

by Lily Meade<br />

Publisher: Sourcebooks. $13<br />

cooking<br />

Goon with the Spoon<br />

by Snoop Dogg and<br />

Earl "E-40" Stevens<br />

Publisher: Chronicle. $22.45<br />

essays<br />

Quietly Hostile<br />

by Samantha Irby<br />

Publisher: Vintage. $12.99<br />

12 aphrochic

ELEVATE<br />

YOUR<br />

STYLE<br />

The New York School of Interior Design offers online and on-campus<br />

programs for everyone—from aspiring designers to professionals.<br />

Take an intro course, or enroll in a grad program. Specialize in fields like<br />

lighting, sustainability, or healthcare.<br />

<strong>No</strong> matter what you choose, we’ll help you design the spaces<br />

where life is lived.<br />

LEARNMORE.NYSID.EDU/APHROCHIC

VISUAL CUES<br />

The Public Art Fund of New York has installed sculptor Fred Eversley’s 12-foot Parabolic Light, a cylindrical<br />

lens work, in the Doris C. Freedman Plaza in Central Park. On display through Aug. 25, 2024, the work<br />

is cast from magenta polyurethane and is the artist's first public sculpture in New York. Eversley is<br />

a groundbreaking artist who was in the vanguard of the Light and Space art movement that started in<br />

Southern California in the 1960s. Trained as an engineer at the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh, Eversley<br />

also worked for NASA's labs, performing experiments with light and sound. He moved to Venice, Calif., in<br />

1964 where he began experimenting with cast resin, polishing it to capture and manipulate light. When a<br />

car accident in 1967 left him on crutches for a year, Eversley turned to art for therapy and work. His unique<br />

approach from both a scientific and artistic view led to his being named the first artist-in-residence at the<br />

Smithsonian Institution's Air and Space Museum. In 1970, he cast his first full parabolic lens in polyester,<br />

launching a body of work that would become his primary focus for over 50 years. Parabolic Light is Eversley’s<br />

first outdoor sculpture and the largest to date in his Cylindrical Lens series. Public Art Fund exhibitions and<br />

programs are supported by individual donors, as well as public funds from government agencies in New<br />

York State. To learn more about the exhibit, the Public Art Fund, or Fred Eversley, go to publicartfund.org.<br />

<strong>14</strong> aphrochic

DIVINE<br />

FEMININITY<br />

BY FARES MICUE<br />

PERIGOLD.COM

COMING UP<br />

Events, exhibits, and happenings that celebrate and explore the African Diaspora.<br />

Tampa Bay Black Heritage Festival<br />

Jan. 5-<strong>14</strong>, 2024 | Tampa Bay<br />

The Tampa Bay Black Heritage Festival is a 10-day<br />

cultural event that features speakers, musicians,<br />

artists, poets, and craftspeople locally and nationally.<br />

The 20-year-old festival includes the two-day Music<br />

Fest, which takes place the weekend of the Martin<br />

Luther King Jr. holiday, as well as its Annual 5K Run/<br />

Walk for Health & Wellness sponsored by Publix.<br />

Learn more at tampablackheritage.org.<br />

Pan African Film & Arts Festival<br />

Feb. 6-19, 2024 | Los Angeles<br />

An Academy Award-qualifying event, the Pan African Film & Arts Festival showcases<br />

over 200 films from established and emerging Black filmmakers from over<br />

40 countries, and in 19 languages. Tens of thousands of attendees are able to view<br />

new short films, documentaries, and long-form films, and attend industry panels,<br />

special events, and installations. Past attendees, judges, and filmmakers include<br />

Denzel Washington, Sidney Poitier, Danny Glover, Idris Elba, Mo’Nique, Kevin<br />

Hart, Jamie Foxx, Forest Whitaker, Phylicia Rashad, Lou Gossett, Jr., Issa Rae, Taraji<br />

P. Henson, Trevor <strong>No</strong>ah, David Oyewolo, Laurence Fishburne, Angela Bassett,<br />

Majid Michel, Alfre Woodard, Blair Underwood, and Kerry Washington. For more<br />

information, go to filmfreeway.com.<br />

Afrobeats in America<br />

Feb. 17, 2024 | Houston<br />

Featuring top African music artists and bands, the AfroBeats<br />

festival offers a music lovers an opportunity to experience<br />

the fusion of African rhythms and beats with American music.<br />

The event takes place on the 12-acre Discovery Green in<br />

downtown Houston. Show organizers are working with the<br />

Nigerian government, through the Ministry of Tourism And<br />

Creative Economy, to highlight artists from Nigeria, as well<br />

as those located in the U.S. The festival also includes food<br />

vendors, fashion designers, a kids' zone, and art installations.<br />

For more information, go to aiafestival.com.<br />

16 aphrochic

THE KINTSUGI<br />

MIRROR<br />

PERIGOLD.COM

THE BLACK FAMILY HOME<br />

Art as Expression in the Black Family Home<br />

Art is an incredibly versatile design tool. It can be the<br />

finishing touch to a room or the starting point. Pieces can<br />

work together or skillfully clash. Occasionally, it can even<br />

be the solution to problems that can’t be solved in any other<br />

way. In all of its forms, painting, sculpture or otherwise, art<br />

can be very overt, making clear statements of a cultural,<br />

social or even political nature, writing the perspective of the<br />

collector into the space in clear and unmistakable terms. In<br />

the Black family home, art is much more than just an investment,<br />

a showcase of status, or flossing. It has a larger and<br />

more important function in our homes — collecting is a form<br />

of self-expression.<br />

In APHROCHIC: Celebrating the Legacy of the Black<br />

Family Home, we present and explore the idea of approaching<br />

a specifically African American design perspective as a<br />

cultural artifact that serves to meet the needs of the people<br />

who create it. Specifically, we identify five needs that design<br />

in the Black family home serves: Safety, Control, Visibility,<br />

Celebration, and Memory. Collectively — though not exclusively<br />

— these five combine to create the feeling of the Black<br />

family home; that vibe that we recognize and cherish and<br />

that we miss when we’re away from it for too long. And art<br />

has a significant role in helping us to find each one.<br />

Control, the freedom to make the choices we want to<br />

make is inherent to design and to picking art for our rooms.<br />

As Black people in America there are few places where we<br />

enjoy the measure of control that we experience at home<br />

and choosing how we decorate our walls, from the images<br />

of Malcolm and Martin that many of us grew up with, to<br />

contemporary works of modern art and photography, is<br />

important in how we express ourselves at home. Similarly,<br />

art can help provide a sense of visibility, celebration, and<br />

memory that is often lacking outside of our houses.<br />

Away from stereotypes, caricature, misrecognitions<br />

A gorgeous hand-beaded<br />

mask from Gabon sits on<br />

the shelf in the library.<br />

The Black Family Home is an<br />

ongoing series focusing on the<br />

history and future of what home<br />

means for Black families.<br />

This series inspired the new book<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong>: Celebrating the Legacy<br />

of the Black Family Home.<br />

Words and Photos by Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

18 aphrochic

THE BLACK FAMILY HOME<br />

and the general dismissals and refutations<br />

of our experiences that accompany<br />

the lopsided power dynamics of white gaze,<br />

choosing art for our homes is an opportunity<br />

for us to be not only seen but recognized,<br />

celebrated as being central to the narrative<br />

and remembered as we are instead of as<br />

someone else prefers to see us. It is the<br />

presence of these feelings, among others,<br />

that provides us with the sense of safety that<br />

enables us to feel at home in our spaces. Like<br />

all foundations, these fundamental needs<br />

are only the beginning — the ends towards<br />

which we design. How we express ourselves,<br />

the means through which we reach those<br />

ends, is as widely diverse as the number of<br />

experiences that we have and the ways in<br />

which we are able to see and convey them.<br />

Like every other part of a designed space,<br />

the unique ways in which art is employed<br />

in the individual home is a reflection of the<br />

people who inhabit the space and the things<br />

that ultimately makes them feel at home.<br />

Though this is the first house we’ve<br />

owned, this farmhouse is the latest in a<br />

series of homes we’ve shared in various<br />

cities across the country, starting with the<br />

first apartment we shared in Philadelphia<br />

in the early 2000s. While the homes were as<br />

different as the cities they were located in,<br />

the simple fact that we were together was<br />

what made each of them feel like home. Our<br />

art collection, like the house itself, is a celebration<br />

of the relationship that brought<br />

us here. Pieces that were picked up as we<br />

moved to DC, California, back home to<br />

Pennsylvania, and then to New York and<br />

sourced during trips to Morocco, France,<br />

Italy, and Germany, have been with us on<br />

the journey, helping us to tell our own story<br />

of home.<br />

As we were designing the AphroFarmhouse,<br />

a lot of thought went into planning<br />

the way that the art we’ve collected over the<br />

years would work in the space. One of the first<br />

decisions was to create a series of themes that<br />

would not only connect the art in different<br />

rooms, but connect the rooms themselves.<br />

Through paintings, sculptures, photographs,<br />

and even condiment dispensers, the art in<br />

the AphroFarmhouse reflects what’s most<br />

important to us. Moreover, different rooms<br />

highlight different art media.<br />

In the living room there is a clear<br />

emphasis on sculpture, while the library<br />

focuses more on imagery, with book covers<br />

displayed as art pieces and framed photography<br />

and figurative paintings on display.<br />

Yet one of the biggest overarching themes<br />

you’ll see when looking at our collection<br />

is the balance of masculine and feminine<br />

energies. Too often, as African Americans,<br />

we find ourselves divided by sex in mass<br />

media representations as well as in our<br />

internal conversations. The Battle of the<br />

Sexes is a divide-and-conquer trope to<br />

which we have proven to be fairly susceptible.<br />

And while there are valid experiences<br />

behind these narratives, the fetishization<br />

of Black women and the disappearance<br />

and attendant conservatization of Black<br />

men is built on the foundation of separation<br />

that it provides. As a counter-narrative, in<br />

our curation we work to create a balance of<br />

masculinity and femininity in the pieces<br />

that we choose and the ways that they are<br />

displayed.<br />

An heirloom velvet painting of Issac<br />

Hayes in the kitchen, a 3D printed bust of<br />

T’Challa (The Black Panther) in the library<br />

and the Jamal Bust in our living room, all<br />

bring overt attention to the Black male<br />

as a figure of artistic attention, calling to<br />

memory the important men in our lives<br />

20 aphrochic

Opposite page, left: A framed art print of an African American couple by Brazilian-based ThingDesign is an ode to Black love.<br />

Opposite page, right: An Ife sculpture from Nigeria was discovered while exploring the souks in the medina of Marrakech.<br />

This page, above: A surrealist self-portrait by Spanish photographer Fares Micue is one of the feminine guardians in the library.<br />

issue fourteen 21

A love of sculpture big and small, a handmade<br />

soapstone chess set from Kenya<br />

has pride of place in the library.<br />

22 aphrochic

issue fourteen 23

THE BLACK FAMILY HOME<br />

and celebrating them as an important part of our culture. While<br />

artwork that celebrates Black women comes in the form of busts<br />

that fill the sculpture garden in our living room, and studies of<br />

the Black female form in pottery and photography that inhabit<br />

our kitchen and library. The library holds some of our favorite<br />

female imagery, including the Trudon candle reproductions of<br />

the Carpeaux sculpture, Pourquoi naître esclave?, and a beautifully<br />

surrealistic self-portrait by photographer Fares Micue. Across<br />

from it hangs an amazing portrait of a Black onna-bugeisha — a<br />

female samurai — by Tim Okamura. Together the two represent<br />

a balance of hard and soft and function as the “guardians” of the<br />

space. Meanwhile, the kitchen is also home to a print of a Barkley<br />

L. Hendricks portrait of a fierce woman in a head wrap, and a<br />

photo of Jeanine’s cousin that first inspired the aesthetic behind<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong>. Just as with the male images, these works invoke the<br />

memory of the women who matter most to us while celebrating<br />

the many sides of Black women.<br />

We balance the two because men and women have both<br />

worked, whether jointly or separately, to shape our culture, guard<br />

our community and nurture our generations. Too often in celebrating<br />

one we lose sight of the other, or in emphasizing a particular<br />

role that one has played, we forget other roles played with<br />

equal ability, overlook the roles that we play equally but differently,<br />

or mistakenly assign roles as responsibilities, unintentionally<br />

limiting the potential and perspective of our own experiences.<br />

The art narrative at the AphroFarmhouse, beginning with the<br />

balance of male and female and proceeding through separate<br />

venerations of each, culminates in the equal joining of the two in<br />

expressions of Black love.<br />

Many of our paintings depict couples, and many of our<br />

statues are arranged together in male and female “couples.”<br />

In the kitchen, two paintings of a couple by Brazilian art brand<br />

ThingDesign sits over the banquette in our breakfast nook. In the<br />

living room, another couple painted by Australian artist Mafalda<br />

Vasconcelos adorns the walls above the sofa. By the front door,<br />

paired masks, masculine and feminine, usher us out the door and<br />

welcome us home when we return. Similarly, small sculpted busts<br />

on the shelves in the library live together as a couple. Though<br />

all art is open to interpretation, we include these paintings and<br />

pairings to reflect what are for us the most ideal elements that<br />

make a relationship feel like home: affection, harmony, partnership,<br />

togetherness, mutual respect and shared comfort.<br />

This collection that has been built over 27 years together, five<br />

cities, and travel to five countries, is filled with pieces that make<br />

us feel at home, that tell our story, that speak to the things that<br />

matters most to us. Our curated collection is a form of self-expression<br />

and ultimately expresses the love we have for one<br />

another. Imagine what story an art collection can tell for you.<br />

Sources for Building A Black Art Collection<br />

The <strong>AphroChic</strong> Art Shop<br />

Earlier this year <strong>AphroChic</strong> began collaborating with<br />

emerging artists from across the African Diaspora. Currently,<br />

our art offerings include limited edition busts by Jessica<br />

Jean-Baptiste, stunning photographs by Fares Micue and a line of<br />

one-of-a-kind mirrors by Candice Luter. More artist collaborations<br />

will be coming in 2024.<br />

BetterShared: Contemporary African Art<br />

At BetterShared you can discover pieces from some of the<br />

world’s most exciting African artists. It’s where we discovered<br />

the work of artists like Neals Niat, Mamus Esiebo, and Lambi<br />

Chibambo. If you’re not sure where to start, you can take an art<br />

style quiz to find pieces that are the perfect fit for your home.<br />

Society6<br />

Society6 is home to a cadre of independent artists from<br />

across the globe. We love perusing the site to find pieces by<br />

Black artists. You can order prints, choose frames, and get them<br />

shipped to your home quickly. They make starting a collection<br />

easy and accessible. AC<br />

"Sisters" by Mafalda Vasconcelos<br />

24 aphrochic

issue fourteen 25

THE BLACK FAMILY HOME<br />

Top left: A sculptural vase from Italy is a celebration<br />

of the Black, female body.<br />

Top right: A bust discovered on Ebay by an<br />

unknown artist, sits in the sculpture garden in<br />

the living room.<br />

Left: Artist Jessie Chen's "The Picnic", showcasing<br />

an African American couple, hangs in the<br />

bedroom.<br />

Right page: FEMME SUCRÉE by Neals Niat is<br />

a reference to a love song from one of the most<br />

popular singers in Cameroon called PETIT PAYS.<br />

The framed piece is a limited edition from the<br />

online contemporary art platform, BetterShared,<br />

that focuses on emerging artists from across the<br />

African Diaspora.<br />

26 aphrochic

issue fourteen 27

THE BLACK FAMILY HOME<br />

Top left: Book covers are displayed as artwork on the shelves<br />

of the AphroFarmhouse library.<br />

Top right: The collection even includes miniature pieces,<br />

including a deck of playing cards by Kehinde Wiley, and cast<br />

pins by Black British artist Dorcas Magbadelo.<br />

Opposite page: "Kalemba III" by Brazilian illustrator, Willian<br />

Santiago, adds vibrance to a corner in the guest bedroom.<br />

28 aphrochic

issue fourteen 29

MOOD<br />

Presents That Celebrate<br />

Their Passions<br />

We love gift-giving season. We truly enjoy<br />

finding that perfect present that speaks to<br />

who the individual is — what they are passionate<br />

about, what they wish for, what they<br />

dream of. Once a year, if we can give them<br />

something that when they open it, they feel<br />

like a child all over again, experiencing a<br />

moment of pure joy and excitement, then<br />

that is the true gift of the season. Here are<br />

30 presents that speak to what a person<br />

loves. Whether hosting, collecting music, or<br />

playing games, these gifts celebrate their<br />

passions and come straight from the heart.<br />

GIFTS FOR<br />

THE HOST<br />

Black Raffia Fringed<br />

Coasters, Set of 4<br />

indegoafrica.org<br />

Royalty Flatware<br />

Multicolor Set $180<br />

post21shop.com<br />

Nguka Limoges Platter<br />

$368<br />

54kibo.com<br />

Jungalow Clay Taper<br />

Candle Holder $20<br />

target.com<br />

30 aphrochic

Sweet July Herringbone<br />

Handcrafted Glass<br />

Decanter & Glasses $119<br />

potterybarn.com<br />

Estelle Cake Stand<br />

in Amber $225<br />

estellecoloredglass.com<br />

Yaël & Valérie Landmark<br />

Cotton Placemats Set of 2<br />

$88<br />

54kibo.com<br />

Boma Napkin Set<br />

starting at $15<br />

sarzastore.com<br />

(Untitled) Pitcher by Kara<br />

Walker $1,500<br />

artwareeditions.com<br />

Nick Cave Ceramic Plates<br />

starting at $65<br />

thirddrawerdown.com<br />

issue fourteen 31

MOOD<br />

Beyoncé Renaissance<br />

Deluxe Edition $48<br />

shopcrateism.com<br />

Tina Turner in Black<br />

And White $285<br />

graciousstyle.com<br />

Jrumz Clarity Headphones<br />

$199.99<br />

jrumzworld.com<br />

Halt Red Boombox<br />

Sculpture, contact for price<br />

artnet.com<br />

Nipsey Hussle Iron on<br />

Embroidery Patch $11.50<br />

etsy.com<br />

32 aphrochic

GIFTS FOR THE<br />

MUSICOLOGIST<br />

Jimi $50<br />

amazon.com<br />

House of Marley Stir It Up<br />

Wireless Turntable $249<br />

amazon.com<br />

Marvin Gaye Dream of a<br />

Lifetime Sweater $100<br />

dreamsoftriumph.com<br />

Larada 6 Legion Guitar<br />

$1,999<br />

abasiconcepts.com<br />

Soldier of Love Pin<br />

$15.50<br />

etsy.com<br />

issue fourteen 33

MOOD<br />

Trendsetters<br />

Puzzle by Grace<br />

Lynne Haynes<br />

$25<br />

newyorkpuzzlecompany.com<br />

Brave. Black. First. Puzzle<br />

$16.99 amazon.com<br />

Matisse’s Model Puzzle x<br />

Faith Ringgold $45<br />

thirddrawerdown.us<br />

Fanous Puzzle by<br />

Roeqiya Fris $34<br />

whiled.co<br />

Ronald Jackson Some<br />

Refused to Work in the<br />

Fields Puzzle $36<br />

apostrophepuzzles.com<br />

34 aphrochic

GIFTS FOR<br />

THE PUZZLER<br />

Derrick Adams x Dreamyard<br />

Double-Sided Jigsaw<br />

Puzzle $16.99<br />

galison.com<br />

Le Dejeuner Jigsaw Puzzle<br />

x Mickalene Thomas $35<br />

thirddrawerdown.us<br />

Black Archives Puzzle:<br />

Two Women $5<br />

ebay.com<br />

Mafalda Vasconcelos<br />

Anathi Puzzle 40.00<br />

jiggypuzzles.com<br />

Tim Okamura Talkin’ All<br />

That Jazz Puzzle $36<br />

apostrophepuzzles.com<br />

issue fourteen 35

FEATURES<br />

Black Is Beautiful | An Artistic Abode | In Search of True Representation |<br />

A Culinary Journey | The Joie of Fellowship | Panama's Rich History |<br />

A Home Within Ourselves | Journey Through Sound

Fashion<br />

Black Is<br />

Beautiful<br />

Bethann Hardison Shares Her Journey In Bringing the<br />

Black Model to the Forefront in INVISIBLE BEAUTY<br />

Black girls hadn’t been seen before is the statement and core sentiment expressed<br />

throughout the documentary film INVISIBLE BEAUTY. The film evokes powerful<br />

emotions in the viewer, kindling feelings of fury and hurt while inspiring viewers<br />

to take action for change. Released in September, the film is a combination of<br />

interviews, photographs, and archival footage, co-directed by French filmmaker<br />

Frédéric Tcheng and Bethann Hardison as a retrospective of Hardison’s life<br />

journey, career, activism, and impact on the fashion industry.<br />

Words by Krystle DeSantos<br />

Photos courtesy of Magnolia Pictures<br />

38 aphrochic

Fashion<br />

With cameras rolling, we are introduced<br />

to Hardison in her New York<br />

apartment, diligently working on her<br />

memoir while deciding on the tone and style<br />

of the documentary's introduction. Her<br />

story spans the breadth of her life from the<br />

early 1940s to present day and takes you on a<br />

journey, from her early years spending time<br />

in the rural south, where segregation was<br />

prevalent, to growing up as a latchkey kid<br />

in the pre-gentrified Bedford-Stuyvesant<br />

neighborhood of Brooklyn.<br />

In the early 1960s Hardison’s career in<br />

fashion began as a long-distance telephone<br />

operator at Cabot, a custom button factory<br />

in the garment district of New York City and<br />

eventually transformed into her becoming<br />

the first Black salesperson in a showroom<br />

while working at Ruth Manchester Ltd., a<br />

junior dress company. In 1967, she was discovered<br />

by the legendary Willi Smith, an<br />

African American designer and pioneer<br />

who popularized streetwear, and she<br />

became his muse and fitting model. Soon<br />

after, Hardison would expand to print and<br />

runway modeling, and in 1973 she became<br />

part of a historical moment in fashion<br />

when she participated in the Battle of Versailles,<br />

which was a fashion show initially<br />

designed to raise money for the Palace of<br />

Versailles’ Marie Antoinette Theater. The<br />

show was a competition of five American<br />

designers against “France’s lions of haute<br />

couture” and it revitalized the American<br />

fashion industry, showcasing American<br />

design from a new perspective, rivaling the<br />

French reputation for elegance and sophistication<br />

while challenging the perception of<br />

American fashion as casual and drab.<br />

In the film, Hardison, who describes<br />

herself as the first "Black, Black model,”<br />

reflects on her experience at the Battle of<br />

Versailles alongside 10 other Black models,<br />

which was unprecedented at the time.<br />

Every step she took was done with intention<br />

as she felt a great sense of responsibility<br />

to represent Black women in an industry<br />

where diversity was very limited. She recalls<br />

how she utilized her performance-based<br />

approach to runway modeling, stopping and<br />

staring boldly with presence at the audience<br />

for a long period of time. This caused the<br />

audience to become excited as they stomped<br />

their feet and screamed “Bravo, bravo!”<br />

Hardison’s work helped to break down<br />

barriers and pave the way for other Black<br />

models to become successful, and by the<br />

early 1980s Bethann’s focus shifted from<br />

modeling to activism within the fashion<br />

industry. She started her own agency<br />

— Bethann Management Agency — and<br />

focused on countering the invisibility of<br />

Black women as well representing a wide<br />

range of ethnicities in fashion, challenging<br />

traditional notions of beauty and diversifying<br />

the industry.<br />

Bethann represented and has been<br />

credited with helping to launch the careers<br />

of many including Veronica Webb, Tyson<br />

Beckford, Kimora Lee Simmons, Ariane<br />

Koizumi, and even her son and actor<br />

Kadeem Hardison, who played the popular<br />

role of character Dwayne Wayne in the '90s<br />

sitcom television series A Different World.<br />

In 1988, Hardison, along with Somali-American<br />

model Iman, co-founded the<br />

Black Girls Coalition as a way to celebrate<br />

and advocate for Black models while raising<br />

awareness for issues including homelessness.<br />

A couple years later, a report by The<br />

City of New York’s Department of Consumer<br />

Affairs was released and it revealed the fact<br />

that only 3.4% of all consumer magazine advertisements<br />

depicted African Americans.<br />

This prompted Hardison and the Black Girls<br />

Coalition to hold a press conference calling<br />

attention to the severe underrepresentation<br />

and lack of diversity in fashion magazines,<br />

runway shows and commercial advertising.<br />

By 1996, Hardison embarked on a<br />

40 aphrochic

issue fourteen 41

Fashion<br />

new journey and closed the doors to her namesake agency,<br />

moving to Mexico. Almost immediately after her move she<br />

began receiving calls with requests for her return and with<br />

reports of Black models being eliminated. Hardison gave it<br />

some time, hoping the pendulum would swing, but by 2007<br />

the modeling scene for major fashion brands became homogeneous<br />

with Eastern European models who appeared to<br />

look like clones of each other.<br />

Black and diverse models were waning from print and<br />

the runway scene due to the industry’s intentional exclusion<br />

and attempt at erasure and this led Hardison to organize a<br />

town hall meeting to address these issues. A year later, she<br />

would collaborate on the creation of Vogue Italia’s “All Black”<br />

issue which exclusively featured Black Models and was Vogue<br />

Italia’s highest-selling issue of all time. It also made history<br />

for Condé Naste by being the first magazine issue to be<br />

reprinted.<br />

Though these endeavors proved to be highly successful,<br />

the fashion industry still failed to adequately represent<br />

the diversity of its consumers and in 2013 Hardison wrote an<br />

open letter to the councils of notable designers and industry<br />

leaders calling out their lack of diversity and requesting<br />

accountability as it pertained to their non-inclusive<br />

white-centric runways. This initiated the formation of The<br />

Diversity Coalitions by Bethann, Iman, and Naomi Campbell<br />

with the main goal of increasing racial diversity. The fashion<br />

industry has made strides in recent years, but there is still<br />

much room for improvement and progress especially as it<br />

relates to equity.<br />

Presently at 81 years of life, Hardison’s ongoing<br />

legacy is not devoid of sacrifice, ambition, tenacity, hope<br />

and change. She is lauded by the likes of Tracee Ellis Ross,<br />

Zendaya, Whoopi Goldberg, Iman, and Naomi Campbell, just<br />

to name a few. Revered as the Godmother of Fashion, her<br />

work continues to leave an indelible mark on the industry.<br />

She is currently on the CFDA's Board of Directors and serves<br />

as Gucci's Executive Advisor for Global Equity and Cultural<br />

Engagement. She is also guiding and mentoring a new generation<br />

of fashion trailblazers and activists, including<br />

Aurora James who is the Founder and Creative Director of<br />

luxury accessories brand Brother Vellies, as well as the<br />

Founder of the Fifteen Percent Pledge, a non-profit advocacy<br />

organization that is closing the racial wealth gap by<br />

partnering with retailers to diversify their shelves and<br />

commit 15% of their purchasing power to Black-owned businesses.<br />

Hardison’s film does one of the things she is well known<br />

for — it provokes conversation and ideas about how each<br />

of us can take action to make a change and strive for more<br />

diversity, inclusion, and equity in fashion and beyond. AC<br />

42 aphrochic

Fashion

“I always know you<br />

can change things.<br />

I've done it before.”<br />

- Bethann Hardison<br />

issue fourteen 45

Interior Design<br />

An Artistic Abode<br />

Huda Hashim’s Contemporary Home is Filled with<br />

Pieces that Celebrate Her Sudanese Heritage<br />

British-born with Sudanese ancestry, artist and designer Huda<br />

Hashim’s home is a beautiful mix of cultures. “I love mixing<br />

African and European themes in this space. The juxtaposition of<br />

cultures, shapes, and materials creates eye-pleasing and balanced<br />

compositions,” she says of her four-bedroom home in Plano, Texas,<br />

that she shares with her husband and two sons.<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Photos by Terica Bowser<br />

issue fourteen 47

Interior Design

Interior Design

Interior Design<br />

In this family home, everything is beautifully<br />

composed. Huda, who is an accomplished<br />

3D architect, painter, and interior designer,<br />

has found a way to perfectly blend modernity,<br />

elegance, neutrals, and bold pops of color<br />

within the space. The founder of two 3D printing<br />

companies, HudArts and Manzili 3D, Huda has<br />

also found success as an artist. Original works<br />

can be spotted throughout the home, some that<br />

are now part of her selection of prints available<br />

at Crate & Barrel.<br />

Like many families in 2020, Huda and<br />

her family found themselves moving into a<br />

new home. And like many, they found that the<br />

process was somewhat different than it had<br />

been in the past. “We got lucky,” she explains,<br />

“We bought our home June of 2020, right in the<br />

middle of COVID and so we didn’t get the opportunity<br />

to see it in person.” With endless<br />

periods of scrolling through the listing photos<br />

and magnifying to see each corner as the only<br />

way to see her new home, there was more than<br />

a bit of trepidation on closing day. Fortunately,<br />

crossing the threshold for the first time<br />

was a happy ending to a long process. “It was<br />

extremely clean, renovated, with marble floors<br />

in the kitchen, breakfast area, and laundry room<br />

and freshly painted walls in a grey-blue tone,”<br />

she says.<br />

The renovated space provided a clean<br />

canvas for the artist and designer. Initially<br />

thinking the home needed new paint and other<br />

changes, she began to focus more on the floor<br />

plan and creating a comfortable environment<br />

for her and her family. “At first I wasn’t too sure<br />

about the paint,” she confesses, “so I got part of<br />

the house painted a warmer color.” But as time<br />

went on and she took stock of the home’s architectural<br />

features and how they interacted with<br />

the design, she found the opportunity to reconsider."<br />

A few months later I realized that the cool<br />

grey-blue was actually the perfect choice due<br />

to the house getting tons of natural light from<br />

our large windows,” she says. “The sunlight was<br />

giving the perfect natural warm tones and so a<br />

cool color balanced out the home.”<br />

In the living room, the layout of the corner<br />

fireplace demanded her attention. “Corner fireplaces<br />

are challenging due to the tendency of a<br />

fireplace to be the focal point of a room. With<br />

that point in a corner and the furniture more<br />

centrally placed, you find yourself working to<br />

create a space with a single cohesive focal point<br />

instead of two focal points that are fighting to<br />

be the center of attention.” She found her way,<br />

creating a balanced room through a selection of<br />

contemporary furnishings. “The curved sofas<br />

are in close proximity to each other to create the<br />

effect of sectional seating and the red sculptural<br />

chairs elevate the look from neutral to the right<br />

amount of color.”<br />

Huda’s brand of cool, streamlined<br />

elegance extended into the home’s dining room,<br />

where modern aesthetics blend with nods to<br />

her past. “This room was inspired by historic<br />

Sudanese palaces with red marble and sculptures,”<br />

she explains. At its center, the statuesque<br />

marble table — a 1970s European design<br />

purchased from a local vintage seller — was<br />

a perfect choice. A painting by Huda is on the<br />

dining room wall. “The artworks in my home are<br />

pieces that were created to be the most raw and<br />

authentic version of myself,” she reflects. The<br />

piece, Path to Light, presents a broad, abstract<br />

landscape highlighted by the work’s impressive<br />

length. An inescapable visual piece, it’s also part<br />

of her collaboration with Crate & Barrel. “It feels<br />

cool to be able to tell people ‘this one is at Crate<br />

& Barrel!’” she laughs.<br />

Somehow, with each space so elegantly<br />

composed, it’s also a space that is kid-friendly<br />

for her two sons. “I grew up around art museums<br />

so I love the clean look of modern shapes that<br />

are also warm, cozy, and inviting,” she remarks.<br />

In the kitchen, which has the feel of an upscale<br />

cafe, Huda reports, “This is the room we use the<br />

most for eating, homework and art projects.”<br />

Designed specifically to be visually cohesive<br />

with the living room, the real value, Huda says, is<br />

in its logistical value. “My breakfast room is cozy,<br />

clean, and most importantly, kid-friendly,” she<br />

smiles.<br />

These days, just about every home can use<br />

a space where the owners can work from home<br />

and when the owner is an artist, that space<br />

needs to be a studio. “My art studio has to be a<br />

issue fourteen 53

Interior Design<br />

place that is not only functional,” Huda relates, “but<br />

one that brings out all the creative juices I need when<br />

painting." To make sure her studio inspires her every<br />

time she steps inside, she covered the floor with a<br />

particularly meaningful pattern. “My choice of this<br />

rug was inspired by the checkered floors of the University<br />

of Khartoum in Sudan, a place thriving with<br />

history and knowledge.”<br />

Huda’s love of history comes through in her<br />

home through treasures including her original<br />

paintings, collection of books, and stylish curiosities<br />

from her travels. In the guest bedroom sits another<br />

of her original paintings depicting the Djingareyber<br />

Mosque, a <strong>14</strong>th century example of Malian architecture,<br />

which still stands today in the city of Timbuktu.<br />

“My [home] holds the richest of items from my<br />

travels around the world. Among other things,<br />

books purchased from local art galleries, they are my<br />

favorite pieces and can’t be found online.”<br />

<strong>No</strong>w Huda’s elegant aesthetic can be part of<br />

homes across the country. Her framed wall art prints<br />

for Crate & Barrel are abstract and organic in neutral<br />

tones, with several pieces exploring historic themes<br />

centered around African architecture. Pieces that<br />

are a perfect example of the design philosophy she<br />

has brought home. “I love creating rooms that are<br />

very artistic and sculptural, elevated with <strong>No</strong>rth<br />

African cultural elements. A perfect balance between<br />

colorful and neutral by playing with textures, shapes<br />

and natural materials.” AC<br />

54 aphrochic

issue fourteen 55

Interior Design

Interior Design

Culture<br />

In Search of True<br />

Representation<br />

Exploring The Black Design Experience<br />

Before and After School<br />

In the American design industry, as in so many other areas of our<br />

society, the question of representation has taken center stage in the<br />

ongoing conversation around race. Even by itself, representation is a<br />

concept of many layers, each of them begging questions of their own.<br />

Yet despite this apparent complexity, the issue is generally approached<br />

from one of two sides: addressing the absence of Black professionals<br />

from design-focused media such as magazines and television shows;<br />

and increasing the number of Black people working in the field.<br />

.<br />

Words by Bryan Mason<br />

Photos furnished by Gail Davis and Taurean Jones<br />

This feature is sponsored<br />

by the New York School of<br />

Interior Design.<br />

60 aphrochic

TELL<br />

YOUR<br />

STORY<br />

Line Study by Candice Luter<br />

Available at Wayfair Professional

Culture<br />

But ultimately the question remains whether<br />

either of these things, or both of them together, will<br />

create meaningful and lasting change. One place<br />

to look for answers is in the experiences of those<br />

designers of color already in the field, and those who<br />

are preparing to enter it.<br />

Designers enter into their profession through<br />

any number of doors, irrespective of heritage. Those<br />

who pursue an academic study of design in anticipation<br />

of a career in its practice present an excellent<br />

opportunity to examine the dynamics of diversity<br />

at the very start of the journey. By definition, a<br />

formal education in the canon of a field is a study in<br />

inclusion and exclusion. But representation is not<br />

only a matter of who is included in the textbooks, but<br />

who is in the classroom to read them.<br />

There are a number of factors contributing<br />

to the absence of Black students from the rolls<br />

of interior design schools. Though many designers<br />

of all backgrounds find the field while searching<br />

for a second or third career, one effect of the lack of<br />

media presence for Black designers is a general assumption<br />

that design is not an economically viable<br />

career for Black people. As a result, many look for<br />

other professional avenues before investigating an<br />

interest in design.<br />

“I took the long way around,” confesses<br />

Taurean Jones, a third-year bachelors student at the<br />

New York School of Interior Design (NYSID). Though<br />

his interest in the field recalls his earliest days in<br />

Southern California, the idea of him pursuing a<br />

career in design initially met with resistance. “I<br />

remember watching a lot of HGTV in the fourth or<br />

fifth grade, and I saw Trading Spaces for kids,” he<br />

recalls. “When my mom asked my brothers and I<br />

what we wanted to be when we grew up, I mentioned<br />

design.” When his mother’s response was less than<br />

enthusiastic, Taurean looked in another direction.<br />

Joining the Air Force at age 20, he spent eight years as<br />

a generator mechanic. The time wasn’t wasted. It led<br />

Taurean to a number of important conclusions. “I<br />

realized the military wasn't for me,” he begins, “and<br />

then after getting out, I knew that design was definitely<br />

what I wanted to do.”<br />

Gail Davis, one of NYSID’s notable Black design<br />

graduates, recounts a similar story. For her, the turn<br />

to design was about more than switching careers, it<br />

was a vital moment of discovering her own voice. “If<br />

you watch the movie The Devil Wears Prada, that was<br />

my life,” she laughs. “I was the assistant to a senior<br />

Gail Davis. Opposite and next page, interiors designed<br />

by Gail Davis.<br />

vice president, later president at Saks, and I was<br />

just burned out.” At the root of her workplace disenchantment<br />

was an experience all too common<br />

for Black women in corporate environments. “I was<br />

tired of white women in higher positions speaking<br />

down to me, calling me things like ‘flighty,’ or<br />

‘airhead.’” After a period of talking herself into and<br />

out of quitting the job, a package delivered to her<br />

boss one day helped clarify the way forward. “It was a<br />

plaque that read, ‘What would you do if you knew you<br />

could not fail?’” As soon as Gail saw it she knew. “I’d<br />

go back to school for design,” she said.<br />

Easily ranking among the nation’s most prestigious<br />

institutes of study for interior design, NYSID<br />

was founded more than a century ago in midtown<br />

Manhattan. Situated in one of America’s most cul-<br />

62 aphrochic

turally diverse cities, with a range of curricula<br />

covering topics as general as basic interior design<br />

certification and as specific as design for healthcare<br />

environments, there are few places better suited for<br />

considering the future of design and the growing<br />

role of representation within it. The school itself<br />

boasts a student population that is nearly 5% Black.<br />

It’s an impressive metric compared to the national<br />

demographic which finds Black designers making<br />

up less than 2% of the profession nationwide.<br />

For Taurean, who also applied to the Rhode<br />

Island School of Design (RISD), choosing NYSID as<br />

the place to pursue his studies came down to the<br />

type of experience the institution promised. “It felt<br />

more like an apprenticeship,” he said of the curriculum.<br />

“You're getting a very focused experience.<br />

I'm in the bachelor’s program now, but the master’s<br />

programs offer the opportunity to focus on specific<br />

topics like lighting and healthcare.”<br />

As a graduate, Gail attributes much of her<br />

success to her alma mater, especially to the professors<br />

who guided her first, uncertain steps into<br />

the classroom. “I had one amazing professor, Ms.<br />

Charlene,” she remembers. “She pulled me aside<br />

the first week of class and said, ‘Let me tell you<br />

something, put your head down and do the work.<br />

You can do this.’” Despite being one of her hardest<br />

professors, Gail also remembers her as among the<br />

most encouraging. “When she didn’t like my work,<br />

she would mark my paper, ‘You're better than this,’”<br />

the designer smiles.<br />

For Gail and Taurean both, the NYSID experience<br />

has been invaluable. Already in the third year of<br />

his bachelor's program, Taurean is honing his focus<br />

on interiors and furniture design. At the same time,<br />

Gail is planning her return. “I have my associate<br />

degree,” she says, “but I want to go back. I want to<br />

go all the way to PhD.” Yet in both cases, a design<br />

education has not changed the experience of an<br />

industry structured to think of diversity as a mission<br />

rather than a reflex. “I’ve had the experience a few<br />

times,” Taurean relates, “where I feel like I don't have<br />

a spot in the room when we’re talking about design.”<br />

Even more troublesome are the moments and experiences<br />

that he can relate to. “I’ve seen experienced<br />

Black, male designers speaking on panels about<br />

difficult experiences. Their stories were immediately<br />

glossed over, and I felt like, if that's how it is for him,

Culture<br />

then I'm not crazy, because I just saw it happen to<br />

somebody else.” Yet the Black designer experience<br />

is a vital and missing part of the conversation in<br />

the design industry, just as the Black perspective<br />

is missing from the conversation on design itself.<br />

“It hits different when it's us,” Gail confides<br />

on designing for Black homes. “Lately, it feels like<br />

I'm emptying my soul into all my projects. It's very<br />

moving for me when my clients go into a space<br />

and they're like, ‘I can't believe this is for me.’”<br />

As the designer confirms, the sentiment stems<br />

from more than the achievement of a luxurious<br />

aesthetic. “It just makes me so happy, because for<br />

so long we've been told what we can’t have, where<br />

we can't go, and what we can't do.”<br />

Conversely, as a professional with a resume<br />

of press features that includes such industry<br />

standards as House Beautiful and Business of<br />

Design, Gail finds that attracting press attention<br />

to her business and projects is no easier in the<br />

current age of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion.<br />

Like Taurean, she has found her access to the<br />

conversation limited by unseen barriers and<br />

unspoken quotas. “I get annoyed that white<br />

people in this industry still pigeonhole us,”<br />

she says. “It’s as if they say, ‘Okay, there's 10<br />

Black designers, but only three of you can get<br />

in.’ There's so many more of us, but they keep<br />

looking in the same places.” And in an industry<br />

that runs largely on visibility and reputation it<br />

can be difficult to advance without a steady diet<br />

of high-profile coverage. “If we're not front and<br />

center,” Gail says, “we just don't get a shot.”<br />

Even the success that Black industry groups<br />

have found in increasing representation in<br />

several leading design publications hasn’t significantly<br />

altered the workings of the industry<br />

because the effects have not been felt equally<br />

throughout the community. “I find it's a challenge<br />

even within organizations that are Black-driven,”<br />

Gail says of gaining high-profile attention. “I<br />

think we have to be kinder to each other and just<br />

not pull from the same three that they pick.”<br />

With their common background as<br />

students of a prestigious interior design school<br />

as a starting point, the experiences that Gail and<br />

Taurean have had from their respective positions<br />

in the design field begin to shed some light on the<br />

complexities of representation and the question<br />

of change. Taurean’s recollections demonstrate<br />

Taurean Jones. Opposite: Furniture designs by Taurean Jones.<br />

the limitations of including more Black people in<br />

the industry, whether as students, professionals,<br />

or panelists, when no additional space is made for<br />

our experiences within the industry or our perspectives<br />

on design. At the same time, Gail highlights<br />

the functional boundaries of increased<br />

media presence, when the additional attention<br />

does not serve to widen the industry’s view of<br />

the diversity already within it. Moreover, even if<br />

executed perfectly, the two together would not<br />

succeed in creating lasting change.<br />

Their experiences point to the fact that<br />

real representation is not only a matter of who<br />

appears on the cover of a magazine or even in<br />

the editor’s chair, but of who owns the magazine.<br />

Likewise, it’s not just a question of who appears in<br />

classrooms to learn or to teach but of who sets the<br />

curricula, who determines the canon, and even<br />

who owns the schools. Without change on those<br />

levels, diversity and representation will never be<br />

more than trends, ushered in and out with the<br />

seasons and at the whim of those who continue<br />

to set the standards at the academic, trade, and<br />

media levels of the industry.<br />

Without space for Blackness as well as Black<br />

people, those who already work in the industry<br />

and those who are preparing to enter into it, will<br />

still do so with the underlying sense that they are<br />

operating alone and at a disadvantage. “What I<br />

need is a community,” Taurean muses, trying to<br />

verbalize what’s missing from his current experience.<br />

“I have mentorship, and the mentor that I<br />

have from ASID is great, but she’s a white woman<br />

with a whole different outlook from mine. So I’m<br />

not seeing people like myself in a bigger way.” <strong>No</strong>t<br />

just a simple matter of visibility, but of the recognition<br />

that he, in his own person, represents<br />

a meaningful part of the cultural aesthetic that<br />

he is being trained to uphold, Taurean is looking<br />

for viable means to make a positive impact on the<br />

changing world before him. “I don't think design<br />

should be or can be exclusive,” he says. “That idea<br />

can’t hold for the coming future unless we want<br />

things to stay exactly as they are, which is not<br />

really possible.”<br />

Schools like NYSID and the interior design<br />

programs may not be the sole solution to the<br />

problem of representation in the design industry,<br />

or as it extends across the nation, but they’re<br />

a good place to start. As one of the pillars of the<br />

design industry most responsible for setting<br />

and upholding its canon, colleges, universities,<br />

and professional schools are the perfect place<br />

to interrogate the perspectives and rationales<br />

that underlie practices, in the process, creating<br />

spaces where students of diverse backgrounds<br />

can be educated into rather that out of their own<br />

experiences. As noted architectural designer and<br />

former director of the Institute for Continuing<br />

and Professional Studies at NYSID, Leyden Lewis<br />

notes, “The curriculum is key. Who is teaching<br />

and who is being taught is invaluable.” AC<br />

66 aphrochic

68 aphrochic

Food<br />

A Culinary Journey<br />

Kenny Gilbert Adds Global Flavors<br />

to Southern Cooking<br />

Too often we associate the chef’s level of skill with the avant-garde in eating<br />

experiences. Small plates, flamboyantly arrayed with unfamiliar yet delicious<br />

dishes cooked in esoteric ways for people with more money than appetite. Chefs,<br />

to us, aren’t usually people who cook the things we grew up with, they don’t make<br />

the stuff we want when we’re really hungry, and they certainly don’t throw down<br />

on the grill. But then there’s Kenny Gilbert.<br />

Chef Kenny Gilbert is a perfect example of the difference between a cook and a<br />

chef. An aficionado of all things culinary almost from birth, the Cleveland native<br />

was cooking on his own grill by age 7 and single-handedly tackling Thanksgiving<br />

dinner for his entire family by 11. Since then, his career has been an award-heavy<br />

parade of diamonds and stars as he has shown off his abilities at hotels, resorts,<br />

and standalone restaurants around the world, along with an impressive run on<br />

season 7 of Top Chef. Chef Gilbert’s recently released cookbook, Southern Cooking,<br />

Global Flavors, is a trip back through his culinary heritage, expressed through the<br />

lens of his international career. The result is a mouth-watering series of dishes you<br />

love — from ribs and burgers, oxtails and rice to collards, cornbread and seafood<br />

— in ways you’ve never imagined. One of our very favorites, his Coffee-Rubbed<br />

Spareribs with Poblano Apple Slaw, is an experience every meat-eater owes<br />

themselves at least once.<br />

issue fourteen 69

Food<br />

"I worked with a chef from the Big Island of Hawaii many<br />

moons ago. One day on the job, he shared with me a Kona<br />

coffee rub that he grew up eating in Hawaii. He used his coffee<br />

rub on a rack of lamb, and I remember how beautiful the<br />

flavors were. I began to play with it, and instead of using Kona<br />

coffee, I tried it with a Colombian and Costa Rican blend.<br />

I felt like it really lent itself to Spanish flavors, like poblano<br />

peppers, cumin, cinnamon, and coriander. Different cultures<br />

that grow coffee use it in different ways, and cooking with it is<br />

a wonderful way to experience the flavors of those cultures."<br />

— Kenny Gilbert<br />

GET THE BOOK<br />

Recipe reprinted from Southern Cooking Global<br />

Flavors. Copyright © 2023 Kenny Gilbert<br />

Photos © Kristen Penoyer<br />

Published by Rizzoli International Publications Inc.<br />

70 aphrochic

Coffee-Rubbed Spareribs with Poblano Apple Slaw<br />

FOR THE ESPRESSO BBQ SAUCE<br />

Makes 8 Cups<br />

4 cups ketchup<br />

1 cup molasses<br />

1 cup packed brown sugar<br />

1 cup apple cider vinegar<br />

1 cup freshly brewed espresso or coffee<br />

Juice or 2 navel oranges (1 ⁄2 cup)<br />

Juice of 2 lemons (1 ⁄4 cup)<br />

3 tablespoons rib rub<br />

2 tablespoons Chef Kenny’s Raging Cajun<br />

Spice, or other Cajun seasoning<br />

2 tablespoons Chef Kenny’s Fried Chicken<br />

Seasoning, or other poultry seasoning<br />

1 tablespoon ground cumin<br />

1 tablespoon kosher salt<br />

1 teaspoon crushed red pepper<br />

FOR THE SLAW<br />

1 cup sour cream<br />

1 ⁄2 cup agave nectar Juice of 2 or 3 limes<br />

(1 ⁄4 cup)<br />

1 tablespoon kosher salt<br />

1 1 ⁄2 pounds green cabbage, grated (6 cups)<br />

1 ⁄4 large poblano pepper, finely diced (1 ⁄4 cup)<br />

1 ⁄4 red onion, sliced (1 ⁄4 cup)<br />

1 ⁄4 bunch cilantro, chopped (1/4 cup)<br />

1 ⁄4 cup dill pickle relish<br />

1 teaspoon Chef Kenny’s Fried Chicken<br />

Seasoning, or other poultry seasoning<br />

FOR THE RIBS<br />

3 slabs St. Louis–style ribs<br />

1 ⁄2 cup Chef Kenny’s Cinnamon Coffee Rub<br />

3 cups Espresso BBQ Sauce (see above)<br />

FOR THE BUILD<br />

12 flour tortillas<br />

Make the Espresso BBQ Sauce<br />

1. In a medium saucepan over a medium heat, whisk the ketchup, molasses, brown sugar, vinegar, espresso, orange and lemon juice, coffee rub,<br />

chicken seasoning, cumin, salt, and crushed red pepper. Bring to a simmer, then reduce the heat to low and cook for 15 minutes.<br />

2. Remove from the heat and set aside until ready to use. (Any leftover sauce can be stored in an airtight container, in the refrigerator, for up to 6<br />

months. It can be used as a substitute for any barbecue sauce.)<br />

Make the Ribs<br />

1. Preheat a smoker with charcoal and hickory wood to 275° or 300°F, or preheat an oven to 300°F.<br />

2. Season the ribs on both sides with the coffee rub.<br />

3. Set the ribs on the grate of the smoker, backbone side down, and cook for 11⁄2 to 2 hours, or until the internal temperature is 165°F. Keep the smoker<br />

on. If cooking in the oven, put the ribs on sheet pans lined with foil and cook for 11⁄2 to 2 hours, or until they reach an internal temperature of 165°F.<br />

Keep the oven on.<br />

4. Transfer each of the slabs to a large sheet of foil, backbone side down. Pour 1 cup of the barbecue sauce over each slab and wrap them in the foil.<br />

5. Return the ribs to the smoker or oven and cook for another 11⁄4 hours, or until they reach an internal temperature of 195°F.<br />

6. Rest the foil-wrapped cooked ribs in a cooler (without ice) for a minimum of 30 minutes and a maximum of 3 hours before serving.<br />

Make the Slaw<br />

1. Whisk the sour cream, agave nectar, lime juice, and salt in a large bowl.<br />

2. Add the cabbage, poblano, onion, cilantro, pickle relish, and chicken seasoning to the bowl and toss. Set aside until ready to serve<br />

The Build<br />

1. Using a sharp chef’s knife, cut the slabs of ribs into three-rib portions. Be sure to cut close to the bone of the next rib; that way every rib will have<br />

meat on the bone.<br />

2. Heat a large cast-iron skillet on medium-high. Warm the tortillas on each side for 10 to 15 seconds, until lightly charred.<br />

3. Place two griddled tortillas on a plate and top with three ribs. Add a small cup of barbecue sauce and some slaw. Plate the remaining servings, and<br />

serve additional slaw and barbecue sauce alongside.<br />

issue fourteen 71

Entertaining<br />

The Joie of<br />

Fellowship<br />

The importance of fellowship and gathering was instilled in<br />

me early as a Nigerian. The need to entertain with fancy table<br />

settings, many utensils, and intimidating etiquette rules,<br />

however, was not. When I was growing up in Austin, Texas,<br />

every Saturday (after garage sale shopping), we would get<br />

dressed up and meet with other Nigerian families through<br />

a group called African Christian Fellowship (ACF). (I would<br />

have preferred to camouflage myself into the couch and watch<br />

cartoons or run around the neighborhood with friends, but<br />

nope; I had no choice. I had to put on a semi-decent outfit<br />

and head of to the ACF.)<br />

Words by Ajiri Aki<br />

Photos by Jessica Antola<br />

72 aphrochic

issue fourteen 73

Entertaining<br />

The group was created as a way for<br />

Nigerian immigrant families to form a<br />

community and connect while also preserving<br />

their culture of origin with their<br />

American-raised children. We ate, we sang,<br />

we played, we talked, and we drank lots of<br />

sugary drinks. (It doesn’t sound too bad,<br />

does it?) The adults loved coming together<br />

after a long week to spend time with their<br />

friends.<br />

If it was a kid’s birthday, there would<br />

be cake and candy alongside the weekly<br />

aluminum foil–covered vats of fried rice,<br />

jollof rice, goat meat, and stew. If one of the<br />

adults had just graduated from university or<br />

a kid had graduated to middle school, there<br />

would be even more cake. We organized<br />

picnics so we could barbecue and conferences<br />

to connect with other chapters of ACF<br />

for more dancing, singing, and food. On<br />

Sundays after church, we sometimes met<br />

up with other friends, both Nigerian and<br />

non-Nigerian, for more music and food.<br />

Essentially, Nigerians notoriously<br />

love gatherings, and from the time I started<br />

forming memories, they put truth to the<br />

words of the early twentieth-century textile<br />

designer William Morris, “Fellowship is life.”<br />

When I moved to New York in my 20s,<br />

after my undergrad years in Texas, I found<br />

another group that valued fellowship:<br />

Mexican girls who had grown up together in<br />

Juarez and El Paso. Mexican culture is very<br />

similar to Nigerian culture in that we both<br />

really love finding excuses to celebrate with<br />

one another in a big way. Mexican weddings<br />

and Nigerian weddings are usually giant, full<br />

of extended family, and party crashers are<br />

welcomed.<br />

I’d meet with this group of friends<br />

every Thursday for juevecitos, which translates<br />

literally to “the little Thursdays.” Every<br />

week, we’d gather at a different girl’s house<br />

to have drinks, eat, and catch up. We were<br />

loud, and 99% of the time, the night ended in<br />

dancing and informal karaoke with no microphones.<br />

The weekly host was in charge<br />

of laying out a buffet of food, but sometimes<br />

we’d all pitch in by bringing a dish, or we’d<br />

order in tamales or tacos. Over the course<br />

of ten years, our group grew to 30-plus girls<br />

and two guys. When someone moved to New<br />

York from Mexico for an internship or a new<br />

job, a friend of a friend would connect them<br />

to us, and they’d join the juevecitos. We even<br />

used an Excel spreadsheet to organize our<br />

gatherings.<br />

GET THE BOOK<br />

Reprinted from Joie. Copyright © 2023 Ajiri Aki<br />

Photograph copyright © 2023 by Jessica Antola.<br />

Published by Clarkson Potter, an imprint of<br />

Random House.<br />

Since living among the French, I have<br />

learned that they share this same love of<br />

gathering. To the French aussi, fellowship is<br />

life. Coming together brings them joy, but it<br />

is also necessary for strengthening relationships<br />

among family and friends, connecting<br />

generations, and building communities.<br />

I daresay it’s absolutely one of the most intriguing<br />

and important elements we can<br />

learn from French culture.<br />

The French gather regularly. They<br />

rarely skip lunch. They often spend dinner<br />

during the week with their family around<br />

the table. On the weekends, meals are notoriously<br />

long. Oftentimes, apéros will extend<br />

into apéro-dinatoires. Even when the<br />

French go on strike or protest — whether the<br />

issue is women’s rights or proposed changes<br />

to the retirement age — it somehow turns<br />

into parades with music and drinks.<br />

So, my life here in France has nourished<br />

that love of gathering that was instilled in<br />

me thanks to my Nigerian heritage and my<br />

induction into Mexican culture. In many<br />

ways, it has helped encourage and ritualize<br />

gathering for me. It is part of my daily life<br />

now, and my raison d’être.<br />

Here, I’ve been allowed to figure out<br />

my own entertaining style, one that feels<br />

less intimidating yet incredibly inspiring.<br />

The French introduced me to l’art de la table,<br />

something I never experienced during those<br />

childhood gatherings, which featured paper<br />

plates, Tupperware, and tin foil. Through<br />

the French, I have been exposed to a whole<br />

new set of tricks and tools to elevate and<br />

enhance everyday gatherings.<br />

When I was fresh off my Air France<br />

flight from New York, my approach to entertaining<br />

consisted of trying to be the “hostess<br />

with the mostest” and home chef extraordinaire.<br />

I had no friends, so I reverted to what<br />

I knew: trying to find a community and fellowship.<br />

As it was for my mother, inviting<br />

people into my home was a way to connect.<br />

But trying to be perfect made it messy. At<br />

74 aphrochic

Entertaining<br />

76 aphrochic

countless dinners or gatherings, I spent half my time mired in details that<br />

didn’t matter—like the <strong>No</strong>ah’s Ark–themed birthday party I planned for my<br />

daughter, when I stayed up until four p.m. making tiny birthday hats for one<br />

hundred little plastic toy animals.<br />

Or the many dinners that I served at 10 p.m., which wouldn’t have been<br />

a big deal in France, except that I had asked my guests to arrive three hours<br />

earlier, and I spent all those hours in the kitchen.<br />

It took me a while — and a French friend asking why in the world I was<br />

going to such trouble — to learn what most French people already know: The<br />

purpose of entertaining is to bring together one’s friends or family and spend<br />

time with them. Focus on the purpose: It should be a pleasure, not a pressure.<br />

The French keep their meals pretty simple, eat them sitting around a table,<br />

and stay at that table for a long time. Leave the fancy food for nights out at<br />

restaurants — especially if cooking is preventing you from being part of the<br />

evening’s festivities—and keep the intention on spending time with your<br />

guests.<br />

Stock your shelves with dishes and bowls and platters you love and<br />